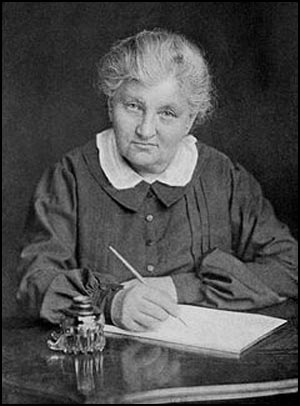

Catherine Breshkovskaya

Catherine Breshkovskaya, the daughter of a prosperous landowner who owned serfs, was born in Vitebsk, Russia, on 13th January, 1844. As a child she developed a strong sympathy for the plight of the rural poor: "Men would come to the master begging for bread; women would come weeping, demanding back their children of whom they had been robbed. These things tormented me as a child, pursued me into my bed, where I would lie awake for hours, unable to sleep thinking of all the horrors that surrounded me."

She later told Louise Bryant: "When I think back upon my past life I, first of all, see myself as a tiny five-year-old girl, who was suffering all the time, whose heart was breaking for some one else; now for the driver, then again for the chamber-maid, or the labourer or the oppressed peasant - for at that time there was still serfdom in Russia. The impression of the grief of the people had entered so deeply into my child's soul that it did not leave me during the whole of my life."

Catherine's parents had liberal views and had welcomed the emancipation of the serfs and had encouraged her at the age of sixteen to open a peasant school on their estate. She later recalled "If there is anything good in me, I owe it all to them." However, she was aware that the freed serfs still had considerable problems: "In one village near ours, where the peasants refused to leave their plots, they were drawn up in a line along the village street. Every tenth man was called out and flogged, and some died. Two weeks later, every fifth man was flogged.... I heard many heart-rending stories in my little school house. The peasants would throng to our house night and day."

According to Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976): "After a year of running the school Catherine began desperately to search for some more general political solution to the local misery she saw around her, and at the age of seventeen, after some conflicts with her parents, she set off alone for the capital. In the train to St Petersburg she found herself sitting next to a man who started talking to her of the early populists. They had gone to the countryside, he said, without any idea of social reconstruction in their minds; they simply wanted to teach the peasants to read, to interest them in new ideas, to give them some medical help and to raise them in any way they could from their darkness and misery. In the process, these young people had been able to formulate some of their ideals for a better society." The man she was talking to was Peter Kropotkin.

In St Petersburg Kropotkin introduced Catherine to various radical circles and helped her to get a job as a private teacher. Catherine later recalled that she met several young women, who like her "had won their personal freedom, now wanted to make use of it, not for their own personal enjoyment but to carry to the people the knowledge that had emancipated them."

Under pressure from her parents she returned to Vitebsk where she opened a school for peasant girls. A few years later she met a local wealthy landowner who shared her views. They married and together they established a co-operative bank and a peasant agricultural school on his estate. She was also a regular visitor to Kiev and and with a couple of friends established a socialist commune in Kiev, that had been influenced by the writings of Alexander Herzen, Peter Lavrov and Pavel Axelrod,

After the birth of her son, Nikolai, she left her child with her sister-in-law and became a full-time revolutionary. She later wrote: "I felt that in my child my youth was buried, and that when he was taken from my body, the fire of my spirit had gone out with him. But it was not so... I knew that I could not be a mother and a revolutionary. Among the women involved in the struggle for freedom in Russia there were many who chose to be fighters rather than members of the victims of tyranny."

Breshkovskaya gave out political leaflets in rural areas: "In one of the villages I gave away my last illegal leaflet and then decided to write an appeal to the peasants myself. Stephanovich made three copies of it... In those terribly ignorant times when the only written papers in the villages were the orders issued by the authorities, their faith in a written word was great, all the more so since there was no one in the villages who could write even moderately well."

Breshkovskaya was eventually arrested by the authorities and after being held in solitary confinement in Kiev Prison for a year. In January, 1878, Breshkovskaya and thirty-six other women were tried for carrying out "revolutionary propaganda". She was found guilty and sentenced to twenty years hard labour in Siberia. She became a well-known international figure when she was interviewed by the American journalist, George Kennan for his book Siberia and the Exile System.

In 1896 Breshkovskaya was allowed to return home and it was not long before she became involved in politics again. Breshkovskaya, like Alexander Herzen believed that any socialist revolution in Russia would have to be instigated by the peasantry. According to Edward Acton, the author of Alexander Herzen and the Role of the Intellectual Revolutionary (1979): "Nineteenth-century Russia was overwhelmingly a peasant society, and it was to the peasantry that Herzen looked for revolutionary upheaval and socialist construction. Central to his vision was the existence of the Russian peasant commune. In most parts of the empire the peasantry lived in small village communes where the land was owned by the commune and was periodically redistributed among individual households along egalitarian lines. In this he saw the embryo of a socialist society. If the economic burdens of serfdom and state taxation were to be removed, and the land of the nobility made over to the communes, they would develop into flourishing socialist cells."

In 1901 Breshkovskaya joined with Victor Chernov, Gregory Gershuni, Nikolai Avksentiev, Alexander Kerensky and Evno Azef, to form the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR) and spent much of her time touring the world making speeches and raising money for the party. The main policy of the SR was the confiscation of all land. This would then be distributed among the peasants according to need. The party was also in favour of the establishment of a democratically elected constituent assembly and a maximum 8-hour day for factory workers.

Breshkovskaya was arrested in 1907 and was sentenced to be exiled to Siberia for life. She was only released after the fall of the overthrow of Nicholas II. When she arrived back in St Petersburg she supported the Provisional Government, that included two members of the SR, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice and Victor Chernov Minister of Agriculture.

In July 1917, Kerensky became prime minister. He invited Breshkovskaya to become one of his advisers and arranged for her to live in the Winter Palace. The journalist, Louise Bryant interviewed Breshkovskaya for her book, Six Months in Russia (1918): "I saw Babushka a good many times after that and found why she lived in this back room on the top floor of the Winter Palace. First, it was because she chose to live there. They had offered her the choice of the beautiful apartments and she had refused anything but this simple room. She insisted on having her bed and all her belongings crammed into the tiny place, and ate all her meals there. I don't know whether it was her long years in prison that made her assume this peculiar attitude, or if it was just because she was a simple woman and very close to the people."

Babushka told Bryant that she was looking forward to the elections for the Constituent Assembly which she believed would result in a victory for the Socialist Revolutionary Party and that Alexander Kerensky would be Russia's first President. However, Kerensky's was overthrown by the Bolsheviks on 24th October, 1917. Lenin, the new leader of the country, gave instructions for elections to the assembly.

The balloting began on 25th November and continued until 9th December. Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17). As David Shub pointed out, "The Russian people, in the freest election in modern history, voted for moderate socialism and against the bourgeoisie."

Lenin was bitterly disappointed with the result as he hoped it would legitimize the October Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was elected President. Nikolai Sukhanov argued: "Without Chernov the SR Party would not have existed, any more than the Bolshevik Party without Lenin - inasmuch as no serious political organization can take shape round an intellectual vacuum. But Chernov - unlike Lenin - only performed half the work in the SR Party. During the period of pre-Revolutionary conspiracy he was not the party organizing centre, and in the broad area of the revolution, in spite of his vast authority amongst the SRs, Chernov proved bankrupt as a political leader. Chernov never showed the slightest stability, striking power, or fighting ability - qualities vital for a political leader in a revolutionary situation. He proved inwardly feeble and outwardly unattractive, disagreeable and ridiculous."

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia.

Catherine Breshkovskaya was upset by these events and decided to live in Czechoslovakia. Breshkovskaya founded Russian-language schools in Ruthenia before retiring to Khvaly, where she died on 12th September 1934.

Primary Sources

(1) Catherine Breshkovska, Memoirs (1917)

Soon we moved to Smela. This enormous country town, which already contained one sugar refinery and six factories, was spread over a wide area. The house of the landlord, with its garden, park, and lake, surrounded by a sea of trees, seemed to draw away from the noisy, dirty streets, which teemed with factory people. The large market place swarmed with traders. The police and fire stations were at the market place. At the end of the place was a pond, its muddy water surrounded by very steep banks. Earthen huts were dug out of these banks, and the shores of the lake were thus lined with habitations resembling dens for animals. In them the workers who came from other places lived-former dvorovye, who had no land, who had come from northern governments. They lived in these huts with their large families; here they were born and here they died.

In Smela we soon found a corner to live in. No one in the town occupied a whole house. Small rooms were rented, usually without tables or seats. The father of the owner of our hut, an old fighter for the welfare of this community, offered us his own room, a dark den, and himself moved into the passage, where he slept on planks. This old man helped me a good deal in understanding the life of the factory population. They had been brought to Smela, when serfdom still existed, from one of the central governments, to work in the factories, having abandoned their land and their houses. With their liberation they had got new small patches of land, but only large enough to build their houses on, and were still obliged to work in the factories, receiving a ration of bread as wages. I do not remember further details, but I know that the factory population lived in constant fear of losing their work at the whim of managers and directors. Those with large families had an especially hard time. Our old man was always weak from hunger. His son had his own family to care for; his daughter-in law was unkind; and the old man, who had been twice flogged and sent to Siberia for defending the common interests, was at the end of his days almost a beggar. An old pink shirt, a jacket, and an old peasant coat were his only clothes. He also had a wooden basin and several wooden spoons, which he kindly put at our disposal.

(2) Catherine Breshkovska, Memoirs (1917)

We directed our steps toward Podolia, but I remember only a little of the details of the journey. In one of the villages I gave away my last illegal leaflet and then decided to write an appeal to the peasants myself. Stephanovich made three copies of it. I did this because when I spoke to the peasants they always said, "If you would write down these words and spread them everywhere, they would be of real use, because the people would know then that they were not invented."

In those terribly ignorant times when the only written papers in the villages were the orders issued by the authorities, their faith in a written word was great, all the more so since there was no one in the villages who could write even moderately well.

(3) Catherine Breshkovska, Memoirs (1917)

Evening was drawing near but the sun had not yet set. I, thinking only of Jacob, was astonished when the chief commissar of the district was announced. It developed that he had been informed of the event by a messenger and had come from the district town of Bratzlav. This stout gentleman entered the hut demanding, "Where is she?" I was still sitting on the trunk eating apples.

"Take her to prison under strong guard. Search her first."

Several women were summoned, and in the closet which I had planned to occupy they, who were full of sympathy and curiosity, timidly searched my shabby, almost beggarly clothes, examined my two rubles pityingly and put them carefully back into my pocket.

An escort was waiting for me in the yard-twelve peasants armed with clubs. They put me in a cart and took me to Tulchin. While wandering about the market I had often wondered about a curiously shaped building. A high wall of planks, pointed at the top, hid this building from sight, only its red tiled roof showing. In my innocence I used to wonder what strange sort of man would build himself such a horrid habitation.

On arriving in Tulchin my cart drove up to this strange building. The wide gates were opened. As we rolled into a bare, dreary yard, a large, thin pig walked slowly about us, grunting plain lively. It had been arrested for trespassing, and since its owner had not appeared it had been starving for a whole week in the prison yard.

The enormous, barn-like building was divided into four big wards. Scores of prisoners could be placed in each of them. At that time they were empty. I was taken into one of them. I had my sack with me, but they had taken out my papers, maps, and tools. The wooden bedsteads were wide and clean. I lay down and went to sleep.

(4) Edward T. Heald, letter to his wife (6th May, 1917)

The Petrograd Soviet was still in session when the Peasants' Convention opened up. Madame Breshkovskaya, the "Grandmother of the Revolution", who has recently returned from the long exile in Siberia, made a strong appeal for real democracy, and the peasants came back strong for democracy and against the radical Bolsheviki. The latter only got two or three votes out of eight hundred.

In the Petrograd Soviet a radical, who had just arrived from New York, by the name of Trotsky, got up and made a demagogic appeal for the overthrow of the Duma and for the putting of the Soviet in power as the government. But the great leaders of the meeting, Kerensky, Tseretelli and Plekhanov, were against him, and the Soviet voted for participation in the Duma Government and a new cabinet by a large majority.

(5) Louise Bryant, Six Months in Russia (1918)

Catherine Breshkovskaya. What richness of romance that name recalls. What tales of a young enthusiast who dared to express herself under the menacing tyranny of a Russian Tsar. An aristocrat who gave up everything for her people; a Jeanne d'Arc who led the masses to freedom by education instead of bayonets; hunted, imprisoned, tortured, almost half a century exiled in the darkness of Siberia, brought back under the flaming banners of revolution, honoured as no other woman of modern times has been honoured, misunderstanding and misunderstood, deposed again, broken.... Catherine Breshkovsky's life was one of sorrow, of disappointment, of disillusionment, but it was a full life. And when the quarrels of the hour are swept aside her page in history will be one of honour and she will be known to all posterity by that most beautiful name on the long records of aspiring mankind-known always as "Babushka," the Grandmother of the Revolution.

For many years Catherine Breshkovsky has been well known in America; it was to sympathetic America, that she always came for assistance. Even in prison she kept in touch with her numerous admirers and champions in this country. I felt a sort of vague connection with her because she knew friends of mine at home, so she was one of the first persons I sought out when I reached Petrograd. Cheap tales, gathered by unsympathetic persons and scattered broadcast abroad, told of her triumphant entrance into Petrograd and Moscow, her brilliant installation on the throne of the Tsar in the Winter Palace, which was rumoured to be draped all in red, how she sat there enjoying the drunken revels of the Anarchists that constantly surrounded her.

I had all this in mind the morning I first went there. Crossing under the famous Red Arch I came out upon the beautiful Winter Palace Square, which is one of the most impressive squares in the world. The immense red buildings stretch away endlessly, giving one the idea of deliberate lavishness on the part of the builder, as if he wanted to demonstrate to an astonished world that there was no limit to his magnificence and his power.

I stopped at the main entrance and asked for Babushka. "Babushka?" repeated the guard. "Go round to the side gate." At the side gate I found other guards who directed me through a little garden and I finally entered the palace by a sort of back door.

The svetzars here told me to climb the stairs to the top floor, and Babushka's room was the last door along the corridor. The Tsar's private elevator, which he had built in recent years, did not work any more and the stairway wound round and round the elevator shaft.

I was ushered right into her room, which was very small-about the size of an ordinary hotel bedroom. There was a desk in one corner, a table and a long couch, several chairs and a bed. It was the kind of room you would pay two or three dollars a night for in an American hotel. Babushka came forward and shook hands with me.

"You look like an American," she said. "Now, did you come all the way from America to see what we're doing with our revolution?"

We sat down on the couch and Babushka went on talking about America, of which she seemed particularly fond. She mentioned many well-known writers here, and called them "her children." I said, "How does it seem to be here in the palace?"

"Why," she answered artlessly and without hesitation, "I don't like it at all. There is something about palaces that makes me think of prison. Whenever I go out in the corridor - did you notice the corridor? - I have a feeling that I must be back in prison - it's so gloomy and forbidding and dark. Personally, I'd love to have a little house somewhere, with plants in the window and as much sun coming in as possible. I'd like to rest... But I stay here because "this man" wants me to." "This man" was Kerensky.

There was a touching friendship between Babushka and Kerensky. In the swift whirl of events the old grandmother was in danger of being forgotten, after people got over celebrating the downfall of the Romanoffs. But Kerensky did not forget. He made her think that she was very necessary to the new government of Russia. He asked her advice on all sorts of things, but whether he ever took it or not is very doubtful. He paid her public homage on many occasions and she loved him like a son.

I saw Babushka a good many times after that and found why she lived in this back room on the top floor of the Winter Palace. First, it was because she chose to live there. They had offered her the choice of the beautiful apartments and she had refused anything but this simple room. She insisted on having her bed and all her belongings crammed into the tiny place, and ate all her meals there. I don't know whether it was her long years in prison that made her assume this peculiar attitude, or if it was just because she was a simple woman and very close to the people. She wrote a little biography of herself on the way back from Siberia in which she said:

"When I think back upon my past life I, first of all, see myself as a tiny five-year-old girl, who was suffering all the time, whose heart was breaking for some one else; now for the driver, then again for the chamber-maid, or the labourer or the oppressed peasant - for at that time there was still serfdom in Russia. The impression of the grief of the people had entered so deeply into my child's soul that it did not leave me during the whole of my life."

Very pathetic, indeed, was her description of what it was like to be free. This feeling she never knew until the news of the revolution was brought to her. "The longer the war lasted," she wrote, "the more terrible were its consequences, the brighter were the basenesses of the Russian Government. The cleaner was the unavoidableness of the democracies of all countries getting conscious, the nearer was also our Revolution."

"I was waiting for the ringing of the bells announcing freedom, and I was wondering why the bells made me wait. And yet, when in November last, bursts of indignation took place, when angry shouts were being transmitted from one group of the population to another, I was standing already with one foot in the Siberian sledge and was sorry that the winter road was fast getting spoiled."

"On the 4th of March a wire reached me in Menusinsk announcing my liberty. The same day I was already on my way to Achinsk, the nearest railway station. From Achinsk began my uninterrupted contact with soldiers, peasants, workmen, railway employees, students and numbers of women - all so dear to me."

Babushka believed that the Constituent Assembly would meet and form a government, and Kerensky ought to be the first President. She intended to tour Russia in a sort of presidential campaign. Of course I wanted to go along. There were always a lot of people around Babushka, so she told me to come down early in the morning and we would have a private talk together.

We walked up and down the corridor. I remember a significant thing that she said to me. "If anything terrible happens to my country it will not be the fault of the working people, but of the reactionaries." She said she was afraid of a serious counter-revolution, but she didn't seem to know how or when it would breaking for some one else; now for the driver, then again for the chamber-maid, or the labourer or the oppressed peasant - for at that time there was still serfdom in Russia. The impression of the grief of the people had entered so deeply into my child's soul that it did not leave me during the whole of my life."

Very pathetic, indeed, was her description of what it was like to be free. This feeling she never knew until the news of the revolution was brought to her. "The longer the war lasted," she wrote, "the more terrible were its consequences, the brighter were the basenesses of the Russian Government. The cleaner was the unavoidableness of the democracies of all countries getting conscious, the nearer was also our Revolution."

She had a plan for educational work which had the approval of President Wilson, and a large fund donated by American philanthropists, but somehow the soldiers and workers did not understand it - they accused her of using the funds for political purposes that were reactionary and against the Soviets. A sad misunderstanding ensued which probably led to all the rumours about Babushka's imprisonment by the Bolsheviki. Nothing of the kind ever occurred. I do not think any one in Russia ever thought of harming Babushka, although she must have been misled into believing this because for a while after the fall of the Provisional Government she was in hiding. But later she lived quietly in Moscow.

There is nothing strange in the fact that Babushka took no part in the November revolution. History almost invariably proves that those who give wholly of themselves in their youth to some large idea cannot in their old age comprehend the very revolutionary spirit which they themselves began; they are not only unsympathetic to it, but usually they offer real opposition. And thus it was that Babushka, who stood so long for political revolution, balked at the logical next step, which is class struggle. It is a matter of age. If Julia Ward Howe were alive - an old woman of eighty - one could hardly expect her to picket for woman's suffrage in front of the White House, although in her youth she wrote the Battle Hymn of the Republic.