1917 Constituent Assembly in Russia

After Nicholas II abdicated, the new Provisional Government announced it would introduce a Constituent Assembly. Elections were due to take place in November. Some leading Bolsheviks believed that the election should be postponed as the Socialist Revolutionaries might well become the largest force in the assembly. When it seemed that the election was to be cancelled, five members of the Bolshevik Central Committee, Victor Nogin, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Vladimir Milyutin submitted their resignations.

Kamenev believed it was better to allow the election to go ahead and although the Bolsheviks would be beaten it would give them to chance to expose the deficiencies of the Socialist Revolutionaries. "We (the Bolsheviks) shall be such a strong opposition party that in a country of universal suffrage our opponents will be compelled to make concessions to us at every step, or we will form, together with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, non-party peasants, etc., a ruling bloc which will fundamentally have to carry out our programme." (1)

On 4th November, 1917, the five men issued a statement: "The leading group in the Central Committee... has firmly decided not to allow the formation of a government of the soviet parties but to fight for a purely Bolshevik government however it can and whatever the sacrifices this costs the workers and soldiers. We cannot assume responsibility for this ruinous policy of the Central Committee, carried out against the will of a large part of the proletariat and soldiers." Nogin, Rykov, Milyutin and Ivan Teodorovich resigned their commissariats. They issued another statement: "There is only one path: the preservation of a purely Bolshevik government by means of political terror. We cannot and will not accept this." (2)

Eventually it was decided to go ahead with the elections for the Consistent Assembly. The party newspaper, Pravda, claimed: "As a democratic government we cannot disregard the decision of the people, even if we do not agree with it. If the peasants follow the Social Revolutionaries farther, even if they give that party a majority in the Constituent Assembly, we shall say: so be it." (3)

Eugene Lyons, the author of Workers’ Paradise Lost: Fifty Years of Soviet Communism: A Balance Sheet (1967), pointed out: "The hopes of self-government unleashed by the fall of tsarism were centered on the Constituent Assembly, a democratic parliament to draw up a democratic constitution. Lenin and his followers, of course, jumped on that bandwagon, too, posing not merely as advocates of the parliament but as its only true friends. What if the voting went against them? They piously pledged themselves to abide by the popular mandate." (4)

The balloting began on 25th November and continued until 9th December. Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, reported: "The elections for the Constituent Assembly have just taken place here. The polling was very high. Every man and woman votes all over this vast territory, even the Lapp in Siberia and the Tartar of Central Asia. Russia is now the greatest and most democratic country in the world. There are several women candidates for the Constituent Assembly and some are said to have a good chance of election. The one thing that troubles us all and hangs like a cloud over our heads is the fear of famine." (5)

Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17).

The elections disclosed the strongholds of each party: "The Socialist-Revolutionaries were dominant in the north, north-west, central black earth, south-eastern Volga, in the north Caucasus, Siberia, most of the Ukraine and amongst the soldiers of the south-western and Rumanian fronts, and the sailors of the Black Sea fleet. The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, held sway in White Russia, in most of the central provinces, and in Petrograd and Moscow. They also dominated the armies on the northern and western fronts and the Baltic fleet. The Mensheviks were virtually limited to Transcaucasia, and the Kadets to the metropolitan centres of Moscow and Petrograd where, in any case, they took place to the Bolsheviks." (6)

It seemed that the Socialist Revolutionaries would be in a position to form the next government. As David Shub pointed out, "The Russian people, in the freest election in modern history, voted for moderate socialism and against the bourgeoisie." Most members of the Bolshevik Central Committee, now favoured a coalition government. Lenin believed that the Bolsheviks should retain power and attacked his opponents for their "un-Marxist remarks" and their criminal vacillation". Lenin managed to pass a resolution through the Central Committee by a narrow margin. (7)

Lenin demobilized the Russian Army and announced that he planned to seek an armistice with Germany. In December, 1917, Leon Trotsky led the Russian delegation at Brest-Litovsk that was negotiating with representatives from Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread from Russia to Germany and Austria-Hungary before he had to sign the treaty. (8)

The Constituent Assembly opened on 18th January, 1918. "The Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries occupied the extreme left of the house; next to them sat the crowded Socialist Revolutionary majority, then the Mensheviks. The benches on the right were empty. A number of Cadet deputies had already been arrested; the rest stayed away. The entire Assembly was Socialist - but the Bolsheviks were only a minority." (9)

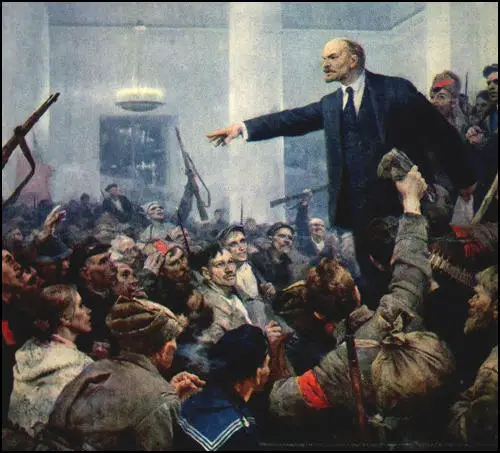

Harold Williams, of the Daily Chronicle reported: "When the Assembly was opened the galleries were crowded, mostly with Bolshevik supporters. Sailors and Red Guards, with their bayonets hanging at various angles, stood on the floor of the House. To right and left of the Speaker's tribune sat the People's Commissars and their assistants. Lenin was there, bald, red-bearded, short and rather stout. He was apparently in good spirits, and chattered merrily with Krylenko (Commander-in-Chief of the Army). There were Lunacharsky and Mme Kollontai, and a number of dark young men who now stand at the head of the various Government departments and devise schemes for the imposition of unalloyed Socialism on Russia." (10)

Yakov Sverdlov was the first to mount the platform. He then read a statement that demanded that all state power be vested in the Soviets, therefore destroying the very meaning of the Constituent Assembly. He added: "all attempts on the part of any person or institution to assume any of the functions of government will be regarded as a counter-revolutionary act... every such attempt will be suppressed by all means at the command of the Soviet Government, included the use of armed force." (11)

This statement was ignored and the members of the Constituent Assembly demanded the election of a President. Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was proposed for the post. The Bolsheviks decided not to nominate their own candidate and instead endorsed Maria Spiridonova, the candidate of the Left Social-Revolutionaries. Spiridonova, since returning to Petrograd from Sibera in June, had become an important figure in the revolution as she believed that fighting a war with Germany meant postponing key reforms. (12)

Chernov won the vote of 244 against 151. In his opening address, Chernov expressed hope that the Constituent Assembly meant the start of stable and democratic government. He welcomed the Bolshevik land reforms and was pleased that the "soil would become the common property of all peasants who were willing and able to till it." However, he broke with the Bolsheviks over foreign policy when he stated that his government would strive for a general peace without victors or vanquished but would not sign a separate peace with Germany. (13)

Irakli Tsereteli the leader of the Mensheviks, rose to speak but was confronted with soldiers and sailors pointing rifles and pistols at his head. "The chairman's appeals for order brought more hooting, catcalls, obscene oaths, and fierce howls. Tsereteli finally managed, nevertheless, to capture general attention with his eloquent plea for civil liberty and the warning of civil war... Lenin did not speak. He sat on the stairs leading to the platform, smiled derisively, jested, wrote something on a slip of paper, then stretched himself out on a bench and pretended to fall asleep." (14)

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. The following day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. "In all Parliaments there are two elements: exploiters and exploited; the former always manage to maintain class privileges by manoeuvres and compromise. Therefore the Constituent Assembly represents a stage of class coalition.

In the next stage of political consciousness the exploited class realises that only a class institution and not general national institutions can break the power of the exploiters. The Soviet, therefore, represents a higher form of political development than the Constituent Assembly." (15)

Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia. Maxim Gorky, a world famous Russian writer and active revolutionary, pointed out: "For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished and tens of thousands of workers and peasants... The unarmed revolutionary democracy of Petersburg - workers, officials - were peacefully demonstrating in favour of the Constituent Assembly. Pravda lies when it writes that the demonstration was organized by the bourgeoisie and by the bankers.... Pravda knows that the workers of the Obukhavo, Patronnyi and other factories were taking part in the demonstrations. And these workers were fired upon. And Pravda may lie as much as it wants, but it cannot hide the shameful facts." (16)

Primary Sources

(1) Morgan Philips Price, letter to Anna Maria Philips (30th November, 1917)

The elections for the Constituent Assembly have just taken place here. The polling was very high. Every man and woman votes all over this vast territory, even the Lapp in Siberia and the Tartar of Central Asia. Russia is now the greatest and most democratic country in the world. There are several women candidates for the Constituent Assembly and some are said to have a good chance of election. The one thing that troubles us all and hangs like a cloud over our heads is the fear of famine.

(2) Morgan Philips Price, Manchester Guardian (15th December, 1917)

Interest in the negotiations commenced yesterday with the Central Powers for a long armistice is overshadowed by the conflict between the Soviet and the Constituent Assembly. The result of the elections for the Constituent Assembly can now be roughly estimated. The small middle-class electors, frightened by Bolshevik terrorism, voted for the large capitalists and the Cadet Party; the urban proletariat and the army and navy went solidly with the Bolsheviks; the poorer peasants of the central provinces supported the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, who are in alliance with the Bolsheviks and have representatives in the Revolutionary Government.

Between these extremes comes the Centre group of the old Socialist Revolutionary Party (Right SRs) which has received the votes of the more well-to-do peasantry of the southern and eastern provinces. These three groups will probably be evenly divided in strength in the Constituent Assembly. Authority will therefore rest with the group which can secure the support of the Centre Party. The leaders of this party, like Chernov, however, are discredited in the army and navy and the urban proletariat on account of their contact with the late Provisional Government, and are accused of having sold the Russian Revolution to the Allied Imperialists. On the other hand, this Centre Party still has a considerable influence among the peasantry and the recently opened Peasant Congress of All Russia showed they had about 35 per cent of all the delegates.

This wholesome brake upon the Bolshevik extremists is evidently frightening the latter, but instead of having a sobering effect it is making them increase the policy of terrorism. The Cadet members of the Constituent Assembly are being arrested and thrown into the St Peter and St Paul Fortress immediately they arrive in Petrograd from the provinces. The apparent object of this is to terrorise all possible opposition to a dictatorship of the proletariat in the Constituent Assembly when the latter commences.

Articles appear in the official Bolshevik organs every day to the effect that the only function of the Constituent Assembly is to serve the will of the proletariat. Even the Left Socialist Revolutionary leaders, who are acting as a brake upon the hot-headed Bolsheviks, say that in transition periods of social reconstruction like the present, authority must rest with the class that made the Revolution. On the other hand they protest against the arrest of Cadets and try to secure the inviolability of members of the Constituent Assembly. But this moderate wing of the Revolutionary Government is powerless to check the mad career of the Anarcho-Syndicalist dictators, who are relying on the bayonets of the army and navy. The soldiers and sailors, both at the front and in the rear, are so embittered by the experiences of the last eight months that they see a dictatorship as the sole form of government which will put an end to the war and crush the capitalist class - which they say made the war - under an iron heel. But they little heed the dangerous precedent which this policy creates. Thus the country becomes every day more sharply divided into two camps - the classes and the masses - and the position of the Moderate Centre, relying on the peasant, becomes increasingly difficult.

Under these circumstances Parliamentary Government becomes an impossibility, and the authority of the Constituent Assembly, which will only reflect these bitter dissensions in a concentrated form, is likely to be small. The soldiers, sailors and workers regard their syndicates or soviets as the sole authority which they will respect, and as long as they have armed forces at their disposal this reign of terror is likely to continue. It is a terrible lesson in what happens when a people, tortured by three years of war, turn on the ruling classes who have exploited and tormented them.

(3) David Shub, Lenin (1948)

In accordance with custom, the parliament was opened by the oldest deputy. From the Socialist Revolutionary benches rose Shvetzov, a veteran of the People's Will. As he mounted the platform, Bolshevik deputies began slamming their desks while soldiers and sailors pounded the floor with their rifles.

Shvetzov finally found a lull in the noise to say: "The meeting of the Constituent Assembly is opened." An outburst of catcalls greeted his words.

Sverdlov then mounted the platform, pushed the old man aside, and declared in his loud, rich voice that the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet of workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies had empowered him to open the meeting of the Constituent Assembly. Then on behalf of the committee he read the "Declaration of Rights of the Labouring and Exploited Masses", written by Lenin, Stalin and Bukharin. The declaration demanded that all state power be vested in the Soviets, thereby destroying the very meaning of the Constituent Assembly.

(4) Nikolai Sukhanov, Russian Revolution 1917: A Personal Record (1922)

In the creation of the SR Party Chernov had played an absolutely exceptional role. Chernov was the only substantial theoretician of any kind it had - and a universal one at that. If Chernov's writings were removed from the SR party literature almost nothing would be left.

Without Chernov the SR Party would not have existed, any more than the Bolshevik Party without Lenin - inasmuch as no serious political organization can take shape round an intellectual vacuum.

But Chernov - unlike Lenin - only performed half the work in the SR Party. During the period of pre-Revolutionary conspiracy he was not the party organizing centre, and in the broad area of the revolution, in spite of his vast authority amongst the SRs, Chernov proved bankrupt as a political leader.

Chernov never showed the slightest stability, striking power, or fighting ability - qualities vital for a political leader in a revolutionary situation. He proved inwardly feeble and outwardly unattractive, disagreeable and ridiculous.