Louise Bryant

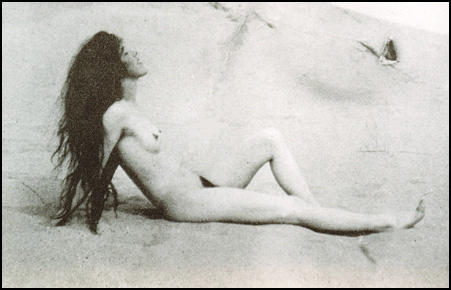

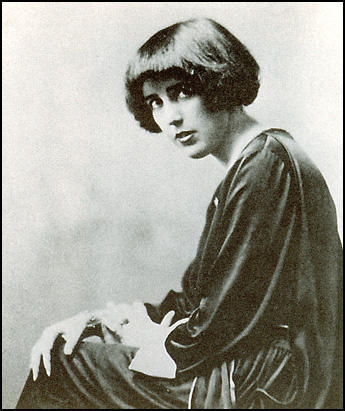

Louise Bryant, the daughter of the radical journalist, Hugh Moran, was born in Reno, Nevada, on 5th December 1885. Later, after the death of her father, she adopted the name of her stepfather, Sheridan Bryant, a railroad conductor. According to her biographer, Barbara Gelb, "she was slender and small-boned with vividly pretty Irish features - reddish-brown hair, a pert nose, mischievous mouth, and blue-gray eyes set widely apart in a heart-shaped face."

Bryant attended the University of Oregon where she became active in the struggle for women's suffrage. According to her biographer, Mary V. Dearborn: "A good student, known as a considerable flirt, she had grown into a beautiful woman, with auburn hair, creamy skin, and very long lashes of which she was vain. Bryant wrote a senior thesis on the Modoc Indian Wars."

Bryant graduated from university in January 1909. She worked briefly in a canning factory in Seattle. Later she claimed that the "grim working conditions and pitifully low wages that prevailed in factories at the time, that aroused her social conscience." She also briefly worked as a schoolteacher before establishing herself as a journalist in Portland working for the Portland Spectator . During this period she mixed with a group of people who held progressive ideas on politics.

On 13th November, 1909, she married Paul Trullinger, a wealthy dentist. Barbara Gelb argues that "Paul regarded himself as a free thinker and some thing of a bohemian and quietly endorsed Louise's radical political views and espousal of the suffrage cause." During this period she became close to Sara Bard Field. She continued to write and in 1912 began contributing to the radical journal, Blast, a San Francisco anarchist weekly edited by Alexander Berkman.

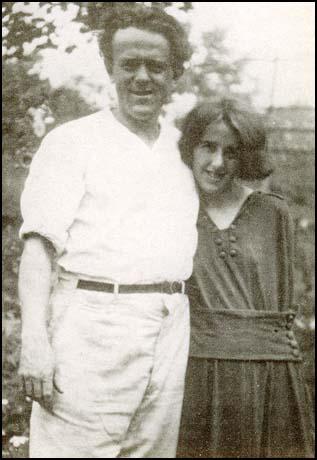

In 1915 Bryant met the radical journalist, John Reed. He told a friend: "I think I've found her at last. She's wild, brave and straight-and graceful and lovely to look at. In this spiritual vacuum, this unfertilized soil, she has grown (how, I can't imagine) into an artist. She is coming to New York to get a job with me, I hope. I think she's the first person I ever loved without reservation." Bryant remarked: "I always wanted somebody who wouldn't care when you went to bed or what hour you got up, and who lived in the way Jack did."

Reed took her to New York City and she was introduced to a group of radicals associated with the journal, The Masses. This included Max Eastman, Sherwood Anderson, Eugene O'Neill, Upton Sinclair, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge, Floyd Dell, Inez Milholland, Carl Sandburg, Crystal Eastman and Boardman Robinson. Bryant began writing for the journal. Waldo Frank got to know her during this period. He later recalled: "She was an Irish beauty, thin, with pale skin, very romantic. She was intellectually alive and responsive, although not profound."

In the summer of 1916 Bryant and Reed decided to rent a home in Provincetown, a small seaport in Massachusetts. A group of left-wing writers including Floyd Dell, George Gig Cook, Mary Heaton Vorse, Susan Glaspell, Hutchins Hapgood, William Zorach, Theodore Dreiser and Neith Boyce, who lived in Greenwich Village, often spent their summers in Provincetown. In previous year, several members of this community, established the Provincetown Theatre Group. A shack at the end of the fisherman's wharf was turned into a theatre. Later, other writers such as Eugene O'Neill and Edna St. Vincent Millay joined the group. Bryant wrote: "It was a strange year. Never were so many people in America who wrote or painted or acted ever thrown together in one place."

On 28th July, 1916 the group performed Bound East for Cardiff, a play written by the young playwright, Eugene O'Neill. The cast included George Gig Cook, John Reed and O'Neill, who was persuaded to play the one-line role of the ship's mate. It was the ideal play for the Provincetown Theatre. Susan Glaspell later recalled: "The sea had been good to Eugene O'Neill. It was there for his opening. There was a fog, just as the script demanded, fog bell in the harbour. The tide was in, and it washed under us and around, spraying through the holes in the floor, giving us the rhythm and the flavour of the sea while the big dying sailor talked to his friend Drisc of the life he had always wanted deep in the land, where you'd never see a ship or smell the sea."

O'Neill's one-act play shared the bill with The Game, that had been written by Louise Bryant. According to Barbara Gelb: "Louise hurried to finish her play, The Game. Though it was a rather stilted attempt at parable... it caught the interest of William and Marguerite Zorach, both artists, who thought they could create an innovative stage setting, and it was accepted for the second bill." Mary V. Dearborn, the author of Queen of Bohemia (1996), remarked: "The play boasted a remarkably overstated and formalized acting style... Utterly, deliberately non-realistic, the play received more acclaim than it perhaps deserved."

In June 1916, John Reed went to see a doctor about his health problems. He was told that he needed an operation to remove one of his kidneys. While he was away Bryant became close to Eugene O'Neill. The author of So Short a Time (1973) argued: "Louise was spellbound by O'Neill's marathon swims. Sometimes after watching him from her window, who would join him on the beach. O'Neill could no longer pretend that he was not deeply and unhappily in love with her... He was convinced that Louise, committed to Reed, would be offended by his love. He not only concealed his feelings, but tried his best to avoid her; he was the only one to whom it was not plain that Louise was pursuing him." Louise sent a note to O'Neill that read: "I must see you alone. I have to explain something, for my sake and Jack's. You have to understand." As a result of the meeting, Louise and O'Neill became lovers and soon most of their friends were aware of it. However, John Reed was completely ignorant of the affair. Dorothy Day, who was a close friend of O'Neill during this period. She later recalled: "we were all so young. We all knew that Gene was in love with Louise, and believed that he was nursing a hopeless passion. we regarded him as a romantic figure - a genius unhappily in love."

On 9th November 1916, Louise married John Reed. Eleven days later, Reed had one of his kidneys removed at an hospital in Baltimore. His friend, Robert Benchley, who worked for the New York Tribune, wrote to him while he was recovering from the operation: "Allow me to to condole with you on your recent bereavement. we never realize. I suppose, what a wonderful thing a kidney is until it is gone. How true that is of everything in life, after all, isn't it?"

In early 1917 Lincoln Steffens suggested that Reed should go to Russia. He was keen that Louise should accompany him and so he helped her to get accreditation as a foreign correspondent to report the war for the Bell Syndicate. The notation clipped to her application read: "I suppose I will have to issue a passport to this wild woman. She is full of socialistic and ultra-modern ideas, which accounts for her wild hair and open mouth. She is the wife of John Reed, a well-known correspondent."

John Reed and Louise Bryant left for Petrograd in August 1917 after Max Eastman and Eugen Boissevain raised money for the trip. As Theodore Draper pointed out: "Max Eastman scraped together the money, and he reached Petrograd in September 1917. Thus he had two months before the Bolsheviks seized power. These were the days that shook John Reed. He went to Russia purely as a journalist, but he was not a pure journalist. He could not resist identifying himself with underdogs, especially if they followed strong, ruthless leaders. Reed was first and foremost a great reporter, but he was at his best reporting a cause he could make his own."

Reed wrote to Boardman Robinson: "We are in the middle of things and believe me it's thrilling. For color and terror and grandeur this makes Mexico look pale." According to Bertram D. Wolfe: "He made his way into the Smolny, where the Bolsheviks had their headquarters; into the City Duma, stronghold of liberal democracy; into the soviets of workers and soldiers and into the soviets of peasants; into barracks, factory meetings, street processions, halls, courts; into the Constituent Assembly, which the Bolsheviks dispersed; into the Winter Palace when it was being defended by student officers and a woman's battalion, and again when it was being overrun and looted. All Russia was meeting, and John Reed was meeting with it."

On another occasion the couple were nearly killed. Bryant later wrote about the incident in Six Months in Russia (1918): " We found ourselves crammed against a closed archway that had great iron doors securely locked. There were twenty in our crowd and about six were Kronstadt sailors. The first victim was a working man. His right leg was shattered and he sank down without a sound, gradually turning paler and losing consciousness as a pool of blood widened around him. Not one of us dared to move. One thing that I remember, which struck me even then, was that no one in our crowd screamed, although seven were killed. I remember also the two little street boys. One whimpered pitifully when he was shot, the other died instantly, dropping at our feet an inanimate bundle of rags, his little faced covered with his own blood. The hopelessness of our position was just beginning to sink in on me when several Kronstadt sailors with a great shout straight into the fire. They succeeded in reaching the car and thrust their bayonets inside again and again. The sharp cries of the victims rose above the shouting, and suddenly everything was sickeningly quiet. They dragged three dead men out of the armoured car and they lay face up on the cobbles, unrecognizable and stuck all over with bayonet wounds."

While in Petrograd she interviewed Alexander Kerensky, the new prime minister: "I had a tremendous respect for Kerensky when he was head of the Provisional Government. He tried so passionately to hold Russia together, and what man at this hour could have accomplished that? He was never wholeheartedly supported by any group. He attempted to carry the whole weight of the nation on his frail shoulders, keep up a front against the Germans, keep down the warring political factions at home."

It took her several weeks before Lenin was willing to see her. "He is a little round man, quite bald and smooth-shaven. For days he shuts himself away and it is impossible to interview him." She compared him with Kerensky: "Kerensky has personality plus... one cannot help but be charmed by his wit and his friendliness... On the other hand, Lenin is sheer intellect - he is absorbed, cold, unattractive, impatient at interruption... Lenin has tremendous power; he is backed by the Soviets... Lenin is a master propagandist. If any one is capable of manoeuvring a revolution in Germany and Austria, it is Lenin... Lenin is monotonous and through and he is dogged; he possesses all the qualities of a chief, including the absolute moral indifference which is so necessary to such a part."

Bryant was able to spend a lot of time with Leon Trotsky: "Trotsky is slight of build, wears thick glasses and has dark, stormy eyes. His forehead is high and his hair black and wary. He is a brilliant and fiery orator... During the first days of the Bolshevik revolt I used to go every morning to Smolny to get the latest news... Running a government was a new task and often puzzling to the people in Smolny. They had a certain awe of Lenin, so they left him pretty well alone, while every little difficulty under the sun was brought to Trotsky. He worked hard and was often on the verge of a nervous breakdown; he became irritable and flew into rages."

Louise Bryant arrived back in New York City on 19th February, 1918. On her return Bryant commented that the Russian Revolution had increased her belief in women's suffrage: "I wish I could believe it, but I can never see spiritual difference between men and women inside or outside of politics. They act and react very much alike; they certainly did in the Russian Revolution. It is one of the best arguments I know in favour of women's suffrage." She added that she had never met a people so kind and generous as the Russians, who refused to hate anybody, and dislike to kill anyone except their officers and oppressors."

On her arrival back she wrote to Eugene O'Neill in Provincetown. At the time O'Neill was living with Agnes Boulton. She later recalled: "Louise wrote that she must see him - and at once. She had left Jack Reed in Russia and crossed three thousand miles of frozen steppes to come back to him - her lover. Page after page of passionate declaration of their love of hers, which would never change. She had forgiven him. What if he had picked up some girl in the Village and become involved? There was no use writing letters - she had to see him! It was all a misunderstanding and her fault for leaving him, for going to Russia with Jack." Boulton persuaded O'Neill not to see Louise.

John Reed arrived back in New York City on 28th April, 1918. He was immediately arrested and charged with Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp for violating the Espionage Act by publishing anti-war articles and cartoons in The Masses. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

Louise Bryant found that Reed's arrest resulted in her losing work. The Philadelphia Public Ledger, which had run her Russian articles, refused to publish a proposed series on Ireland. "In view of the fact that your husband has again been arrested, I think it would be wiser for you to let the matter rest a while. Your identity as Mrs. Reed has been pretty widely established, and I am afraid the newspapers would not go in for a series from you until Mr. Reed has cleared up all his troubles."

In February, 1919, Bryant was arrested after she spoke at a rally where an effigy of President Woodrow Wilson was burned. Bryany went on hunger-strike and she was soon released. She later explained: "If you go without food and become weak, the authorities let you out because they do not want you to die in jail." The New York Times commented the day after her release: "There may be some who will regret that she was not permitted to test that strike to its fullest limit, like so many of the victims of the Bolshevism of which she approves."

JJohn Reed returned to Russia in 1920 and attended the Second Congress of the Communist International in Moscow. According to the author of Strange Communists I Have Known (1966): "The order of business for the Second Congress had been determined by Lenin. Having concluded that the great push for world revolution had failed, and with it the attempt to smash the old socialist parties and trade unions, Lenin set it as the task of all revolutionaries to return to or infiltrate the old trade unions. As always, Lenin took it for granted that whatever conclusion he had come to in evaluation and in strategy and tactics was infallibly right. In the Comintern, as in his own party, his word was law."

Reed and other members of the Communist Party of the United States and the Communist Party of Great Britain disagreed with this policy and tried to start a debate on the subject. To do so, they needed to add English to the already adopted German, French and Russian, as an official language of debate. This idea was rejected. Reed became disillusioned with the way Lenin had become a virtual dictator of Russia. His friend, Angelica Balabanoff later recalled: "When he came to see me after the Congress, he was in a terrible state of depression. He looked old and exhausted. The experience had been a terrible blow."

Louise Bryant arrived in Moscow in September 1920. She wrote to Max Eastman that she "found him older and sadder and grown strangely gentle and ascetic." In another letter to her mother she remarked that he was tired and ill and close to a breakdown." Louise later recalled: "He was terribly afraid of having made a serious mistake in his interpretation of an historical event for which he would be held accountable before the judgment of history."

On 28th September, John Reed complained of dizziness and headaches. A doctor confirmed he was suffering from typhus. Louse wrote to her mother: "I got permission to stay with him although it is no means customary to allow any one but doctors and nurses to remain with a patient." Louise later recalled: "He was never delirious the way most typhus patients are. He always knew me and his mind was full of stories and poems and beautiful thoughts. He would tell me that the water he drank was full of little songs."

John Reed died on 19th October, 1920. He was given a state funeral and buried in the Kremlin Wall. Louise wrote to Max Eastman: "I haven't the courage to think what it is going to be like without him. I have never really loved any one else in the whole world but Jack, and we were terribly close to each other... No one has ever been so alone as I am. I have lost everything now."

Clare Sheridan was devastated by the death of John Reed: "Everyone liked him and his wife, Louise Bryant, the War Correspondent. She is quite young and had only recently joined him. He had been here two years, and Mrs. Reed, unable to obtain a passport, finally came in through Murmansk. Everything possible was done for him, but of course there are no medicaments here: the hospitals are cruelly short of necessities. He should not have died, but he was one of those young, strong men, impatient of illness, and in the early stages he would not take care of himself."

In her book, Russian Portraits (1921), she described the funeral that was also attended by Nickolai Bukharin and Alexandra Kollontai: "It is the first funeral without a religious service that I have ever seen. It did not seem to strike anyone else as peculiar, but it was to me. His coffin stood for some days in the Trades' Union Hall, the walls of which are covered with huge revolutionary cartoons in marvellously bright decorative colouring. We all assembled in that hall. The coffin stood on a dais and was covered with flowers. As a bit of staging it was very effective, but I saw, when they were being carried out, that most of the wreaths were made of tin flowers painted. I suppose they do service for each Revolutionary burial... A large crowd assembled for John Reed's burial and the occasion was one for speeches. Bucharin and Madame Kolontai both spoke. There were speeches in English, French, German and Russian. It took a very long time, and a mixture of rain and snow was falling. Although the poor widow fainted, her friends did not take her away. It was extremely painful to see this white-faced, unconscious woman lying back on the supporting arm of a Foreign Office official, more interested in the speeches than in the human agony."

Bryant continued work as a journalist and published a second book, Mirrors of Moscow, in 1923. She also published interviews with Benito Mussolini and Enver Pasha. In 1924 she married the former assistant secretary of state William Christian Bullitt. The author of Queen of Bohemia (1996) has argued: "What did Louise Bryant see in Bill Bullitt? At first, it seems, not much - beyond a pleasant dinner companion and a man in a position to help her. Jack Reed, so much admired by Bullitt, had never particularly liked him... Certainly Bill's politics, both before and after the peace mission, were in line with Louise's - though she and Jack may have had reservations because of his great wealth... With his retreat from the world of public affairs, Bullitt seemed to be turning his back on a life of propriety and convention. He would never exactly be bohemian, but he was iconoclastic enough to do what he pleased and defy the expectations of both of his tightly constructed social class and the status quo in general, a quality Louise would have fully appreciated."

Bullitt and Bryant spent time with Lincoln Steffens and his young girlfriend, Ella Winter, while they were living in Paris. Winter later wrote in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "We saw much of Louise Bryant and Billy Bullitt, Louise very pregnant in an Arabian Nights maternity gown of black and gold that I thought could have been worn by a Persian queen. Billy hovered over her like a mother hen." Anne Moen Bullitt, was born in 24th February, 1924.

Justin Kaplan has argued that Bullitt was not an easy man to live with: "Bullitt was an emotional man, not always entirely rational. Indeed... Bullitt's faults were as excessive as his good qualities. Arrogance he possessed in great measure, as well as a sense of entitlement that went hand in hand with a belief in a levelling democracy. He was an impatient man, who, when he decided on a course of action, could not be swayed from it. He did not take advice well."

While in France he began work on a satirical novel about the wealthy people he knew growing up in Philadelphia. His biographer, Mary V. Dearborn, has pointed out: "The hero is John Corsey, a class-bound Philadelphia aristocrat who works as a newspaperman. He falls in love with the sculptor Nina Michaud, a character closely modeled on Louise, but marries Mildred, the socially proper woman his mother has chosen for him, who bears a distinct resemblance to Ernesta. Mildred is frigid, and an unhappy John is impotent. At the novel's end he rediscovers Nina, who has borne him an illegitimate son, a Communist rebel hero clearly based on Jack Reed."

It's Not Done was published in 1926. The New York Herald Tribune described it as "a triumph of audacity" and a "tour de force". The New York Times claimed that it was "a propaganda novel, directed against a single institution, the American aristocratic ideal, and whose defect is that the smoke does not quite clear away so that one can accurately count the corpses." Several reviewers commented on the "frank sexual discussions and steamy love scenes". It was a great commercial success, selling more than 150,000 copies and going into twenty-four printings.

Bullitt's marriage to Bryant did not always run smoothly. The historian, Kenneth S. Davis, claimed that Bullitt was not an easy man to live with: "Ardent, charming, brilliant, highly emotional, a romantic idealist of conspiratorial temper for whom everything was purest white or deepest black (from the first to last he had an excessively vivid sense of plot and counterplot going on all around him), he had several characteristics of the spoiled rich boy who won't play if he can't make the rules."

In 1928 Bryant developed Adiposis dolorosa. As Mary V. Dearborn pointed out: "It causes its sufferers so much pain that they frequently resort, as did Bryant, to drugs or alcohol." Bryant wrote to Art Young: "I suppose in the end death gets all of us. It nearly has got me now."

William Christian Bullitt objected to Bryant's heavy drinking, especially as he felt it was damaging her ability as a mother. On 28th September, 1929, Bullitt discovered letters that indicated that Bryant was having a sexual relationship with the sculptor Gwen Le Gallienne. When confronted with this information, Bryant attempted suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping pills and was admitted to the Neurological Institute of New York. Soon afterwards Bullitt obtained a divorce and gained custody over his daughter, Anne Moen Bullitt, following his testimony that his wife was having a lesbian relationship with Gallienne.

Louise Bryant died in Sèvres in on 6th January 1936. Newspaper accounts said that her death was caused by a cerebral hemorrhage. She had collapsed while climbing the stairs to her room in the Hotel Liberia.

Primary Sources

(1) John Reed, letter to a friend about meeting Louise Bryant (December, 1915)

I think I've found her at last. She's wild, brave and straight-and graceful and lovely to look at. In this spiritual vacuum, this unfertilized soil, she has grown (how, I can't imagine) into an artist. She is coming to New York to get a job with me, I hope. I think she's the first person I ever loved without reservation.

(2) Mabel Dodge, Intimate Memories (1933)

Soon I heard that he had bought the little Sharkey house, where I had hurt him so badly, but he had taken a room in Washington Square and he had met a girl down there and taken her to live with him. I was curious about her, and one later afternoon I knocked at his door. It was opened by a very pretty, tall, young woman with soft, black hair and very blue eyes, who held a lighted candle in her hand.

"Is Jack Reed here?" I asked.

He appeared suddenly behind her with rumpled hair and hurt eyes, and his temples shining as of old.

"This is Louise Bryant," he told me gravely.

"How do you do?" I asked her, but she didn't tell me. "Reed, I came to ask you for your old typewriter, if you're not using it." "Louise is using it," he said.

"Oh, all right. I only thought ..."

Actually, I only talked to him once again, though he was often near me in Croton and I heard pregnantly of the two of them living in the Sharkey Cottage.

(3) Louise Bryant, letter to John Reed (4th July, 1917)

You are the only person in the world I tell everything to and we have been and are such wonderful friends. I'm glad you said what you did about being a good friend, besides a lover. I think that's why we were able to see this through.... I'm sorry I wrote you all those blue, hysterical letters. I'm quite ashamed. I want to come home as much as ever but quite tranquilly, sweetheart, quite whole and healthy-not broken. You said I'd forget things if I was normal. I guess I am, because I've forgotten. Sometimes I wonder how I would feel if it all happened again. I can't think - I can't believe it will. I don't have nightmares and things like that any more. Sometimes I feel I can't bear it away from my honey - but it's a different feeling - not the awful mad need I used to have when I first left.

(4) On 23rd October, 1917, Louise Bryant and John Reed visited the Red Guards defending the Winter Palace.

They said they had no objection to our being in the battle; in fact, the idea rather amused them. One of them was not over eighteen. He told me that in case they were not able to hold the Palace, he was "keeping one bullet for himself." All the others declared that they were doing the same.

Once while we were quietly chatting, a shot rang out and in a moment there was the wildest confusion. Through the front windows we could see people running and falling flat on their faces. We waited for five minutes, but no troops appeared and no further fighting occurred.

(5) Louise Bryant and John Reed were on the street when men in a car opened fire on them. Bryant wrote about the incident in her book Six Months in Russia (1918)

We did not have time to seek shelter. We found ourselves crammed against a closed archway that had great iron doors securely locked. There were twenty in our crowd and about six were Kronstadt sailors. The first victim was a working man. His right leg was shattered and he sank down without a sound, gradually turning paler and losing consciousness as a pool of blood widened around him. Not one of us dared to move. One thing that I remember, which struck me even then, was that no one in our crowd screamed, although seven were killed. I remember also the two little street boys. One whimpered pitifully when he was shot, the other died instantly, dropping at our feet an inanimate bundle of rags, his little faced covered with his own blood.

The hopelessness of our position was just beginning to sink in on me when several Kronstadt sailors with a great shout straight into the fire. They succeeded in reaching the car and thrust their bayonets inside again and again. The sharp cries of the victims rose above the shouting, and suddenly everything was sickeningly quiet. They dragged three dead men out of the armoured car and they lay face up on the cobbles, unrecognizable and stuck all over with bayonet wounds.

(6) Louise Bryant, Six Months in Russia (1918)

I had a tremendous respect for Kerensky when he was head of the Provisional Government. He tried so passionately to hold Russia together, and what man at this hour could have accomplished that? He was never wholeheartedly supported by any group. He attempted to carry the whole weight of the nation on his frail shoulders, keep up a front against the Germans, keep down the warring political factions at home.

(7) In her book Six Months in Russia, Louise Bryant described watching the burial of a man killed during the Russian Revolution.

A woman tried to hurl herself after a coffin as it was being lowered. She forgot the revolution, forgot the future of mankind, remembered only her lost one. With all her frenzied strength she fought against her friends who tried to restrain her. Crying out the name of the man in the coffin, she screamed, bit, scratched like a wounded wild thing until she was finally carried away moaning and half conscious. Tears rolled down the faces of the big soldiers.

(8) Agnes Boulton, Part of a Long Story (1958)

Louise Bryant wrote that she must see him - and at once. She had left Jack Reed in Russia and crossed three thousand miles of frozen steppes to come back to him - her lover. Page after page of passionate declaration of their love of hers, which would never change. She had forgiven him. What if he had picked up some girl in the Village and become involved? There was no use writing letters - she had to see him! It was all a misunderstanding and her fault for leaving him, for going to Russia with Jack.

(9) Barbara Gelb, So Short a Time (1973)

Almost immediately after reaching New York, Louise did a somewhat mystifying thing. She wrote to O'Neill in Provincetown, urging him to come to New York to see her. Apparently she had decided to re-establish the triangle, in spite of her protestations of loyalty to Reed.

To some of Louise's women friends, who advocated and practiced free love, her attachment to two men was perfectly understandable. But these women, for the most part, conducted their affairs quite openly. If they had more than one lover, they took no pains to conceal the fact from either one. Louise's maneuvering and deception puzzled them.

Louise's motives were complex. She seemed to have a compulsive need to court danger. Risk stimulated her. When she was not enduring such realistic dangers as traveling through a war or revolution, she created a situation in which she could evoke stress. Keeping an intense romance going with two men simultaneously, concealing the truth from both, was a way of creating such a situation. In spite of her earlier and perfectly sincere conviction that Reed was the man she wanted, it seemed that monogamy was not, for her, a fulfilling state.

But she could not confront this difficulty. She had married Reed, and apparently needed the security of that marriage. Therefore, she could not be honest with Reed and chance losing him. And she had to entice O'Neill by inventing a false picture of her relationship with Reed - or lose him. For her, it seemed to be less a question of being torn by two lovers, than of playing an exciting game for its own sake.

(10) The New York Times (March, 1919)

Miss Bryant appears a demure and pretty girl, with a large hat, a stylish suit and gray stockings. Her voice is high, but it has a plaintive note to it. She amuses the crowd, because, with the air of an ingenue, she hurls darts at Government departments, holds people up to ridicule, and with a fearful voice appeals to American fair play to be just to a beneficent Bolshevist Government and give it a chance.... In the burst of applause the demure little speaker sits down.

(11) Louise Bryant, letter to Max Eastman on the death of John Reed (October, 1920).

He was never delirious the way most typhus patients are. He always knew me and his mind was full of stories and poems and beautiful thoughts. He would tell me that the water he drank was full of little songs... I haven't the courage to think what it is going to be like without him. I have never really loved any one else in the whole world but Jack, and we were terribly close to each other... No one has ever been so alone as I am. I have lost everything now.

(12) Mary V. Dearborn, Louise Bryant (2002)

This trip to Russia was a turning point in their lives, both in terms of their political consciousness and their careers as journalists. With Reed carrying credentials from the socialist New York Call and the cultural monthly Seven Arts, and Bryant from the Metropolitan, Seven Arts, and Every Week, they were present for the most stirring events of the time: they interviewed Kerensky, leader of the provisional government; they heard of Lenin's disguised re-entry into the country in October. And they saw and reported the events leading up to the Revolution: the Bolsheviks' walkout from the pre-Parliament preparing for the Constituent Assembly, and Lenin's insistence that the Bolshevik Central Committee place armed insurrection on the agenda. The appointment by the Bolsheviks of a Military Revolutionary Committee to protect the garrison, after rumors that Kerensky meant to move the capital to Moscow in order to cede Petrograd to the Germans.

Reed's Ten Days that Shook the World and Bryant's Six Red Months in Russia are the offspring of their experience. They are two very different books. Though both writers shared an enthusiasm for the revolutionary cause, and though both were steeped in the nuances of events and personalities and had a highly developed sense of the politics that went on just before, during, and in the wake of the Revolution, they had widely differing agendas.

Bryant had been charged by her news services to give "the woman's point of view," while Reed had no specific charge. Bryant was an equality feminist, believing that total equality between the sexes must be a key goal of any reform, radical, or revolutionary politics. She scorned such reforms as legislation that would protect women, seeing that such reforms would emphasize and re-inscribe differences between men and woman. So to her the charge given to write "from a woman's point of view" excluded absolutely nothing. Although her book includes portraits of the educator Aleksandra Kollontay and the revolutionary Marie Spirodnova that are insightful and meaningful models of intellectual reportage, Bryant was more interested in painting a picture of a society in which equality of the sexes had been mandated and was becoming a reality.

Reed's account was meant for the history books. He collected documents of all kinds, republishing them in Ten Days; he recorded speeches and included them, sometimes without comment. The book, then, is an invaluable piece of reportage, a historical document that is almost totally accurate. But much of this material is undigested in any way; Reed did not see comment and interpretation as among his historical duties. To the contemporary reader the account seems laden down by details, an un-synthesized historical record. The work of a master journalist and historian, Ten Days was intended to be the first installment of a life work on Russian history. Reed's single-minded goal - to recreate that history - informs every page of the book.

While striving for accuracy as assiduously as Reed, Bryant saw her mission in Six Red Days in Russia as something quite different. More the work of a talented journalist than Ten Days' historian, Bryant's Six Red Months is an attempt to observe, record, and interpret events, personalities, political issues, and daily life before and after the Revolution. If Reed's book gives the "big picture," history as made by great men, Bryant is more interested in looking at and describing Russian life as it was lived by the masses themselves.

The author of Six Red Months is free with her opinions, and ever attuned to the need to communicate with her readers. The book is filled with phrases like "We must somehow make an honest attempt to understand what is happening in Russia" and "We have here in America an all too obvious and objectionable view of Russia. And this, you will agree, is based on fear." Such language puts her on the same footing as her readers, someone who will tell the truth and make sure she is understood. She never hesitates to broach an opinion: in describing Spirodonova's belief that women are more conscientious than men, and Angelica Balabanov's belief that women treasure freedom more than men do, Bryant objected in her narrative. "I wish I could believe it," she wrote, but I can never see spiritual difference between men and women inside or outside of politics. They act and react very much alike; they certainly did in the Russian revolution. It is one of the best arguments I know in favour of women's suffrage."

The narrative of Six Red Months in Russia is engrossing and vivid. While few might admit it, many historians of this period seem to have relied more heavily on Bryant's account than on Ten Days. Her sweep was large: she described her journey into Russia, conditions in Petrograd, the tense atmosphere at the Winter Palace before its overthrow, the formation of the constituent assembly, the state of the military camps, free speech in the new regime, the decline of the church, and even her journey out of Russia by way of Sweden. Little escaped her eye.

During the four months she spent in Russia (not six), Bryant came into her own as a journalist and a professional. She was aware of her great luck that she was working side by side with Reed; their presence together no doubt invested their respective narratives in inestimable ways. A poem she gave to Reed for Christmas, in the wake of the Revolution, conveys her love for him, her pride in what they had been through together, and the joy in working side by side, as reporters and as fellow revolutionaries.

(13) Mabel Dodge, Intimate Memories (1933)

Finally they (John Reed and Louise Bryant) went to Russia, like so many others looking for an escape. For Louise it was an opportunity to be on her way, and she wrote quite a good book; for Reed it was adventure again and perhaps a chance to lose himself in a great upheaval. He threw himself into action close to Trotsky and Lenin and when he died of typhus the Russians gave him a splendid public funeral and set a stone with a tablet to his memory over his grave, and Louise, draped in crepe, the wife of a hero, threw herself on his bier long enough to be photographed for the New York papers.

(14) Clare Sheridan, Russian Portraits (1921)

24th October, 1920: We have all been very much saddened by the death from typhus of John Reed, the American Communist. Everyone liked him and his wife, Louise Bryant, the War Correspondent. She is quite young and had only recently joined him. He had been here two years, and Mrs. Reed, unable to obtain a passport, finally came in through Murmansk. Everything possible was done for him, but of course there are no medicaments here: the hospitals are cruelly short of necessities. He should not have died, but he was one of those young, strong men, impatient of illness, and in the early stages he would not take care of himself.

I attended his funeral. It is the first funeral without a religious service that I have ever seen. It did not seem to strike anyone else as peculiar, but it was to me. His coffin stood for some days in the Trades' Union Hall, the walls of which are covered with huge revolutionary cartoons in marvellously bright decorative colouring. We all assembled in that hall. The coffin stood on a dais and was covered with flowers. As a bit of staging it was very effective, but I saw, when they were being carried out, that most of the wreaths were made of tin flowers painted. I suppose they do service for each Revolutionary burial.

There was a great crowd, but people talked very low. I noticed a Christ-like man with long, fair curly hair, and a fair beard and clear blue eyes; he was quite young. I asked who he was. No one seemed to know. `An artist of sorts,' someone suggested. Not all the people with wonderful heads are wonderful people. Mr. Rothstein and I followed the procession to the grave, accompanied by a band playing a Funeral March that I had never heard before. Whenever that Funeral March struck up (and it had a tedious refrain), everyone uncovered; it seemed to be the only thing they uncovered for. We passed across the Place de la Revolution, and through the sacred gate to the Red Square. He was buried under the Kremlin wall next to all the Revolutionaries his Comrades. As a background to his grave was a large Red banner nailed upon the wall with the letters in gold: "The leaders die, but the cause lives on."

When I was first told that this was the burying ground of the Revolutionaries I looked in vain for graves, and I saw only a quarter of a mile or so of green grassy bank. There was not a memorial, a headstone or a sign, not even an individual mound. The Communist ideal seemed to have been realised at last: the Equality, unattainable in life, the Equality for which Christ died, had been realisable only in death.

A large crowd assembled for John Reed's burial and the occasion was one for speeches. Bucharin and Madame Kolontai both spoke. There were speeches in English, French, German and Russian. It took a very long time, and a mixture of rain and snow was falling. Although the poor widow fainted, her friends did not take her away. It was extremely painful to see this white-faced, unconscious woman lying back on the supporting arm of a Foreign Office official, more interested in the speeches than in the human agony.

The faces of the crowd around betrayed neither sympathy nor interest, they looked on unmoved. I could not get to her, as I was outside the ring of soldiers who stood guard nearly shoulder to shoulder. I marvel continuously at the blank faces of the Russian people. In France or Italy one knows that in moments of sorrow the people are deeply moved, their arms go round one, and their sympathy is overwhelming. They cry with our sorrows, they laugh with our joys. But Russia seems numb. I wonder if it has always been so or whether the people have lived through years of such horror that they have become insensible to pain.