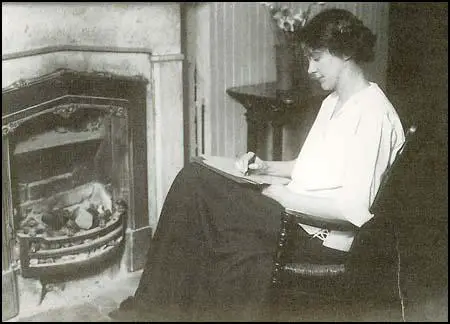

Susan Glaspell

Susan Glaspell, the daughter of Elmer Glaspell and Alice Keating, was born in Davenport, Iowa on 1st July 1876. She graduated from Drake University in Des Moines in 1899 and found work as a journalist with the Des Moines Daily News.

On 2nd December, 1900, John Hossack was murdered with an axe as he slept. His 57-year old wife, Margaret, was charged with the killing. Glaspell covered the trial for her newspaper. The jury did not believe her story that she slept through the killing, even though she lay next to her husband as he was murdered and she was found guilty.

According to the authors of Midnight Assassin: A Murder in America's Heartland: "Although Glaspell had little exposure to criminal law, she initially approached the case like a detective; she personally investigated the murder, visiting the Hossack farmhouse, interviewing the attorneys, and studying the inquest testimony... The case made an indelible impression on Glaspell."

Glaspell's first novel, The Glory of the Conquered, was published in 1909. It received a series of impressive reviews. The New York Times critic argued: "Unless Susan Glaspell is an assumed name covering that of some already well-known author - and the book has qualities so out of the ordinary in American fiction and so individual that this does not seem likely - The Glory of the Conquered brings forward a new author of fine and notable gifts."

Soon afterwards she met two other writers from the town, Floyd Dell and George Jig Cook. Dell later wrote: "Susan was a slight, gentle, sweet, whimsically humourous girl, a little ethereal in appearance, but evidently a person of great energy, and brimful of talent; but, we agreed, too medieval-romantic in her views of life." Barbara Gelb added that she was a "delicate, sad-eyed, witty woman." A journalist who worked with her on the Des Moines Daily News described her as "a strikingly handsome young lady with a nobility of character and charm of manner that command more than passing attention."

Glaspell next novel was She published the Visioning (1911) and the following year had a collection of short-stories, Lifted Masks, published. During this period she began living with George Jig Cook. The couple moved to Provincetown, a small seaport in Massachusetts. They joined a group of left-wing writers including Floyd Dell, John Reed, Mary Heaton Vorse, Mabel Dodge, Hutchins Hapgood, Neith Boyce and Louise Bryant.

In 1915 several members of the group established the Provincetown Theatre Group. A shack at the end of the fisherman's wharf was turned into a theatre. Later, other writers such as Eugene O'Neill and Edna St. Vincent Millay joined the group. The play, Suppressed Desires, that she co-wrote with his husband George Jig Cook, was one of the first plays performed by the group.

As Barbara Gelb, the author of So Short a Time (1973), has pointed out: "Cook and Susan Glaspell had participated, along with Reed, in the birth of the Washington Square Players in Greenwich Village and had written a one-act play to help launch a summer theater in Provincetown in 1915. Cook dreamed of creating a theater that would express fresh, new American talent, and after his modest beginning in the summer of 1915, began urging his friends to provide scripts for an expanded program for the summer of 1916. None of his friends were professional playwrights, but several, like Reed, were journalists and short-story writers. Their unfamiliarity with the dramatic form was, in Cook's opinion, precisely what suited them to be pioneers in his new theater and to break up some of the old theater molds; Cook wanted them to disregard the rules and precepts of the commercial Broadway theater, and to stumble and blunder and grope their way toward a native dramatic art."

Glaspell also wrote Trifles (1916), a play based on the John Hossack case, for the group. It has been argued that the play is an example of early feminist drama. Heywood Broun was one of those who saw the significance of the play: "No direct statements are made for the benefit of the audience. Like the women, they must piece out the story by inference... The story is brought to mind vividly enough to induce the audience to share the sympathy of the women for the wife and agree with them that the trifles which tell the story should not be revealed."

J. Ellen Gainor has argued: "Widely regarded as the most tightly structured and thematically compelling of Glaspell's dramas, Trifles has been repeatedly anthologized and produced, standing as an exemplar of the one-act play form in numerous studies of the genre.... Her vivid use of offstage characters in Trifles will become a hallmark of her playwriting, recurring in Bernice, Inheritors, and Alison's House, among others. Mysteries and the process of deduction also recur throughout her plays, making Trifles both a representative work and one that adumbrates the themes and methods of many of her subsequent drarnas. Moreover, with Trifles she develops her technique of conscious manipulation of audiences' perspectives, so that they can see as she has done, which then allows her feminist and other progressive political views to come to the fore."

Other plays by Glaspell written during this period included The People (1917), The Outside (1917), Woman's Honour (1918), Inheritors (1921) and The Verge (1921). Glaspell acted in some of these plays. Her biographer, Linda Ben-Zvi, has pointed out in Susan Glaspell: Her Life and Times (2005): She was a natural actor in her own work, and her performances in subsequent plays would be equally praised for their naturalness and power." William Zorach, who worked with her in the Provincetown Theatre Group has argued that "Susan Glaspell was a marvelous actress. Acting played a minor part in her life, but she had that rare power and quality inherent in great actresses. She had only to be on the stage and the play and the audience came alive."

Glaspell suffered several miscarriages. She later wrote: "Jig and I did not have children. Perhaps it is true there was a greater intensity between us because of this. Even that, we would have forgone." Floyd Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933) that Glaspell relationship with George Jig Cook was very difficult: "For Susan Glaspell my respect and admiration grew immensely; it is a difficult position to be the wife of a man who is driven by a daemon, a position from which any mortal woman might, however great her love, shrink in dismay or turn away in weariness; but it was a position which she maintained with a sense and radiant dignity."

Many of the productions that appeared at Provincetown were later transferred to New York City. These were initially performed at an experimental theatre on MacDougal Street but some of the plays, especially by Susan Glaspell were extremely well-received. Rebecca Drucker of the The New York Tribune wrote on 20th April 1919: "It is incredible that some enterprising manager has not seized upon the exceedingly high gifts of Susan Glaspell. She is fresh and original genius in the theatre - shrewdly aware of human values, satiric and sensitive."

The Provincetown Theatre Group came to an when its star writer, Eugene O'Neill, decided to deal directly with Broadway. As Floyd Dell pointed out: "George Cook had come to a crisis in his life; he was spiritually centered in the plays of Eugene O'Neill, and now the young playwright had decided to deal directly with Broadway, refusing to allow the Provincetown Players to put on his plays before they went uptown. This was an entirely reasonable decisions on his part, but it broke George Cook's heart."

George Jig Cook eventually came to the conclusion that the Provincetown Theatre Group had failed: "Three years ago, writing for the Provincetown Players, anticipating the forlornness of our hope to bring to birth in our commercial-minded country a theatre whose motive was spiritual... I am now forced to confess that our attempt to build up, by our own life and death, in this alien sea, a coral island of our own, has failed. The failure seems to be more our own than America's. Lacking the instinct of the coral-builders, in which we could have found the happiness of continuing ourselves toward perfection, we have developed little willingness to die for the thing we are building. Our individual gifts and talents have sought their private perfection." The two main figures in the group, Cook and Glaspell, suspended operations and moved to Greece.

Glaspell had to visit the United States but when she returned she found him unwell: "Jig was not well. I found him thinner when I returned from America, and he was thinner now than then. He would get tired of the food.... His thinner face, and his beard, made him look older. His moustache was black, like the eyebrows, but the beard, like his hair, was white... He looked like a man of the mountain; more and more his eyes were the eyes of a seer."

Cook was diagnosed as suffering from typhus or glanders. However, he was too weak to be taken to Athens. The doctor told Susan Glaspell that he was dying: "Most of the time was unconscious, but I could call him to a moment's consciousness. His eyes and mine could meet, and know. I came to feel I must not do it, that it might call him into what I must shield him from knowing... It was at midnight of the second day that Jig, who had been in much distress, fell back on his pillows. His breathing slowed. There came that moment when he did not breathe again."

George Jig Cook died on 14th January, 1924. Floyd Dell wrote: "I loved him, and I would have had his life and death other than they were. I would have him die for Russia and the future, rather than Greece and the past." Greek Coins: Poems of George Cram Cook was published posthumously in 1925. An account of her life with Cook, The Road to the Temple, appeared in 1926.

Glaspell's plays became very popular in Britain. Edith Craig, the daughter of Ellen Terry, had established a feminist theatre group, the Pioneer Players. They had initially performed Trifles and this was followed in March 1925, with a production of The Verge. The review in The Manchester Guardian claimed that "Susan Glaspell is the greatest playwright we have had writing in English since George Bernard Shaw began. I am not sure she is not the greatest dramatist since Ibsen." James Agate, the famous drama critic argued: "Nobody whose genius was less than Ibsen's could have hoped to tackle such a theme. I stand my ground. The Verge is a great play."

Glaspell returned to Provincetown and a book of short-stories, A Jury of Her Peers was published in 1927. The title story was again based on the John Hossack case. This was followed by two novels, Brook Evans (1928) and The Fugitive's Return (1929). She also wrote the play, Alison's House, for which she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. Eugene O'Neill sent her a message that said: "An honor long overdue!!"

Glaspell had a long, passionate relationship with the writer Norman Matson. Neith Boyce wrote to Hutchins Hapgood that: "I see Susan occasionally, but always with constraint. She is completely in love and absorbed in Norman, coos over him and flatters him, and looks like a fat cat." However, in 1932 he left her and married Anna Walling, the daughter of William English Walling and Anna Strunsky.

Glaspell, like her good friend, Eugene O'Neill, suffered from alcoholism and during the 1930s she wrote very little. She confided to Dorothy Meyer, "I have to find out if I don't write because I drink or drink because I don't write." Glaspell was now desperately short of money and her friend Hallie Flanagan, arranged for her to become Midwest Bureau Director for the Federal Theater Project, a project that was part of the New Deal program.

While living in Chicago she decided to try and give up alcohol. According to Mary Heaton Vorse: "Susan's greatest battle took place in a small apartment in Chicago. It was there she conquered her drinking demon and went on to write once more." On her return to Provincetown she produced three novels, The Morning Is Near Us (1939), Norma Ashe (1942) and Judd Rankin's Daughter (1945).

Susan Glaspell died on 27th July 1948.

Primary Sources

(1) In his autobiography Homecoming, Floyd Dell wrote about how George Gig Cook met Susan Glaspell in 1903.

George and I called upon Susan Glaspell, a young newspaperwoman who began a brilliant career as a novelist. She read us some of her just-finished novel, The Glory of the Conquered, the liveliness and humour of which we admired greatly, though George deplored to me on the way home the lamentable conventionality of the author's views of life. Susan was a slight, gentle, sweet, whimsically humourous girl, a little ethereal in appearance, but evidently a person of great energy, and brimful of talent; but, we agreed, too medieval-romantic in her views of life.

(2) Patricia Bryan and Thomas Wolf, Midnight Assassin: A Murder in America's Heartland (2005)

Although Glaspell had little exposure to criminal law, she initially approached the case like a detective; she personally investigated the murder, visiting the Hossack farmhouse, interviewing the attorneys, and studying the inquest testimony. ... The case made an indelible impression on Glaspell. More than fifteen years later ... the haunting image of Margaret Hossack's kitchen came rushing back to Glaspell. In a span of ten days, Glaspell composed a one-act play, Trifles ... A year later, Glaspell reworked the material into a short story titled A Jury of Her Peers.

(3) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

So I went out on the wharf, sat alone on one of our wooden benches without a back, and looked a long time at that bare little stage. After a time the stage became a kitchen-a kitchen there all by itself. I saw just where the stove was, the table, and the steps going upstairs. Then the door at the back opened, and people all bundled up came in-two or three men, I wasn't sure which, but sure enough about the two women, who hung back, reluctant to enter that kitchen.... I hurried in from the wharf to write down what I had seen. Whenever I got stuck, I would run across the street to the old wharf, sit in that leaning little theatre under which the sea sounded, until the play was ready to continue. Sometimes things written in my room would not form on the stage, and I must go home and cross them out.

(4) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

For Susan Glaspell my respect and admiration grew immensely; it is a difficult position to be the wife of a man who is driven by a daemon, a position from which any mortal woman might, however great her love, shrink in dismay or turn away in weariness; but it was a position which she maintained with a sense and radiant dignity.

(5) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

It was in Chicago he (George Cook) was married, to a girl of beauty and charm whom he met through friends there, and after a summer at the Cabin they went to California, where jig will teach English at Leland Standford University under Professor Anderson, his old teacher. Already he has the idea, which grows important in his life, that it is better a writer make his living in some other way than by writing. It seemed to him that this either conscious or unconscious adapting of one's work to what it will mean in money was as a blight. He thought there were ways of freeing oneself ; he cared enough about it to shape his life toward that ideal of giving the mind free play.

(6) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

We hauled out the old boat, took oars and nets and anchors to various owners, bought lumber at the second wharf "up-along," and Jig, Nordfeldt, Ballantine, Joe O'Brien, others helping, converted the fish-house into the Wharf Theatre, a place where ninety people could see a play, if they didn't mind sitting close together on wooden benches with no backs. The stage, ten feet by twelve, was in four sections, so we could have different levels, could run it through the big sliding-door at the back, a variety of set surprising in quarters so small.

We gave a first bill, then met at our house to read plays for a second. Two Irishmen, one old and one young, had arrived and taken a shack just up the street. " Terry," I said to the one not young, " Haven't you a play to read to us?"

"No," said Terry Carlin, " I don't write, I just think, and sometimes talk. But Mr. O'Neill has got a whole trunk full of plays," he smiled.

That didn't sound too promising, but I said: "Well, tell Mr. O'Neill to come to our house at eight o'clock to-night, and bring some of his plays."

So Gene took "Bound East for Cardiff" from his trunk, and Freddie Burt read it to us, Gene staying out in the dining-room while the reading went on.

He was not left alone in the dining-room when the reading had finished.

Then we knew what we were for. We began in faith, and perhaps it is true when you do, that "all these things shall be added unto you."

I may see it through memories too emotional, but it seems to me I have never sat before a more moving production than our "Bound East for Cardiff," when Eugene O'Neill was produced for the first time on any stage. Jig was Yank. As he lay in his bunk dying, he talked of life as one who knew he must leave it.

The sea has been good to Eugene O'Neill. It was there for his opening. There was a fog, just as the script demanded, fog bell in the harbour. The tide was in, and it washed under us and around, spraying through the holes in the floor, giving us the rhythm and the flavour of the sea while the big dying sailor talked to his friend Drisc of the life he had always wanted deep in the land, where you'd never see a ship or smell the sea.

It is not merely figurative language to say the old wharf shook with applause.

The people who had seen the plays, and the people who gave them, were adventurers together. The spectators were part of the Players, for how could it have been done without the feeling that came from them, without that sense of them there, waiting, ready to share, giving-finding the deep level.

(7) Linda Ben-Zvi, Susan Glaspell: Her Life and Times (2005)

Trifles takes only thirty minutes to perform, but in that time Susan is able to offer one of the most powerful plays ever presented by the Provincetown Players, a work that riveted the first audience who saw it in the summer of 1916 and is still able to speak as forcefully to audiences around the world in the twenty-first century, a credit to its author's skill and a mark of how little has changed in the intervening years. It begins as five characters enter the kitchen of an isolated, rural farmhouse where a murder has been committed. A man has been strangled while he slept; and his wife, who claimed to be sleeping beside him at the time, has been accused of the crime and taken to jail to await trial. Those prosecuting the case, County Attorney Henderson and Sheriff Peters, have returned to the scene to search for "something to make a story about-a thing that would connect up with this strange way of doing it. Accompanying them are a neighbor farmer, Mr. Hale, who found the body; Mrs. Peters, the sheriff's wife, who has the task of bringing the accused woman some things; and Mrs. Hale, who keeps Mrs. Peters company while the men move around the upstairs bedroom and perimeter of the farmhouse searching for clues.

Left alone in the kitchen, the women, with furtive glances and few words, slowly construct their own theories about the crime. As they imagine her, Minnie Foster Wright is a lonely, childless woman, married to a taciturn husband, isolated from neighbors because of poverty and the rigors of farm life. When they discover a birdcage, its door ripped off and a canary, its neck wrung, they have no trouble mating the connection: the husband killed the bird, the wife's only comfort, just as he strangled her birdlike spirit. She, in turn, strangled him - a punishment to fit his crime. The motive and method of murder become as clear to them as the signs of sudden anger they infer from the half-wiped kitchen table and Minnie's erratic quilt stitching." Based on such circumstantial evidence, the women try the case, find the accused guilty, but dismiss the charges, and hide the evidence from the men, since their verdict is justifiable homicide. By so doing, Susan is able to create a new type of modern theatre, not based on actions observed by characters or audience but on the "reading" of actions and the construction of narratives depending on individual interpretations and subjective frames of reference. The question of truth becomes moot in the play. Minnie's guilt is not the issue; the real focus is on the ways in which the women are able to intuit her motives, drawing their interpretations from their own lives. In the ways in which they bond together and take action, the women become a true "jury of her peers."

While she keeps many of the details of the original Hossack case, Susan makes certain alterations. Of the original names of the participants, only Henderson is used, assigned to the country attorney rather than the defense lawyer. Margaret Hossack has been renamed Minnie Foster Wright, the pun on the surname marking her lack of "rights" and perhaps implying her "right" to act against her abusive husband. Susan adds Mr. Hale, a composite of the Indianola farmers who testified at the Hossack trial. She also changes the murder weapon, from an ax to a rope, the perfect dramatic correlative for the strangulations the play depicts. Her most striking alterations are her excision of the wife and the change of venue from the courthouse to the kitchen. In the play Minnie never appears. Since the audience never sees the accused woman, it is not swayed by her person but, rather, by her assumed condition, that of an abused wife, driven to commit a terrible act.

Susan displays extraordinary skill in constructing this brief play, her first independent theatre work. With only a stove, chairs, and assorted kitchen items as props-those "trifles" the men derisively dismiss and overlook-she creates a powerful muse-en-scene that uses expressionistic touches to externalize Minnie's desperate state of mind. Things are barren, broken, cold, imprisoning, and violent. Susan also moves beyond realism by choosing a conventional form, well-known to her audience - the detective story - and then systematically dismantling it. In her version the lawmen are quickly shunted offstage to roam about on the periphery of the action, their presence marked theatrically by their shuffling sounds above the heads of the women, another expressionistic touch. She thus undercuts the male authority wielded in the original case and throws into question masculine-sanctioned power in general.

(8) Christopher Bigsby, Critical Introduction to Twentieth-Century Drama (1982)

Besides Eugene O'Neill, the Provincetown Players produced one major talent in Susan Glaspell. Her work is in many ways more controlled than O'Neill's. Her style is more reticent.... Yet she shared her husband's visionary drive, his sense of a Nietzschean life force operating as a counterweight to a tragic potential. And this breaks through on occasion in lyrical arias, apostrophes to the human spirit, at times unbalancing and sentimental, at times affecting in the simplicity of their expression.

(9) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

People sometimes said, "Jig is not a business man," when it seemed opportunities were passed by. But those opportunities were not things wanted from deep. He had a unique power to see just how the thing he wanted done could be done. He could finance for the spirit, and seldom confused, or betrayed, by extending the financing beyond the span he saw ahead, not weighing his adventure down with schemes that would become things in themselves.

He wrote a letter to the people who had seen the plays, asking if they cared to become associate members of the Provincetown Players. The purpose was to give American playwrights of sincere purpose a chance to work out their ideas in freedom, to give all who worked with the plays their opportunity as artists. Were they interested in this ? One dollar for the three remaining bills.

The response paid for seats and stage, and for sets. A production need not cost a lot of money, Jig would say. The most expensive set at the Wharf Theatre cost thirteen dollars. There were sets at the Provincetown Playhouse which cost little more. He liked to remember " The Knight of the Burning Pestle " they gave at Leland Standford, where a book could indicate one house and a bottle another. Sometimes the audience liked to make its own set.

"Now Susan," he said to me, briskly, "I have announced a play of yours for the next bill."

"But I have no play!"

"Then you will have to sit down tomorrow and begin one." "I protested. I did not know how to write a play. I had never "studied it."

Nonsense," said Jig. "You've got a stage, haven't you?"

So I went out on the wharf, sat alone on one of our wooden benches without a back, and looked a long time at that bare little stage. After a time the stage became a kitchen, - a kitchen there all by itself. I saw just where the stove was, the table, and the steps going upstairs. Then the door at the back opened, and people all bundled up came in - two or three men, I wasn't sure which, but sure enough about the two women, who hung back, reluctant to enter that kitchen. When I was a newspaper reporter out in Iowa, I was sent down-state to do a murder trial, and I never forgot going into the kitchen of a woman locked up in town. I had meant to do it as a short story, but the stage took it for its own, so I hurried in from the wharf to write down what I had seen. Whenever I got stuck, I would run across the street to the old wharf, sit in that leaning little theatre under which the sea sounded, until the play was ready to continue. Sometimes things written in my room would not form on the stage, and I must go home and cross them out. " What playwrights need is a stage," said Jig, "their own stage."

(10) Linda Ben-Zvi, Susan Glaspell: Her Life and Times (2005)

By the summer of 1918, Susan had known Eugene O'Neill for two years; they were colleagues, fellow workers, and the leading playwrights of the Provincetown Players. At the outset of their relationship, the younger man had kept his distance, preferring to spend time with his male friends Terry Carlin and Hutch Collins or with a number of women, including Nina Moise and Dorothy Day, who served as surrogates for Louise Bryant. However, during the preceding fall something had happened that altered O'Neill's life and his relationship with Susan. The twenty-four-year-old writer Agnes Boulton, recently widowed, had come to the Village to try to sell some of her romance fiction, in order to support her daughter, parents, and the dairy farm she owned in Connecticut. Her only contacts were Christine Ell, whom she had met previously, and Mary Pyne. At a reunion with Christine at the Hell Hole, she was introduced to O'Neill, who was immediately taken with this dark-haired woman with large, soulful eyes. "I want to spend every night of my life from now on with you," he told her, at the end of their first evening together, as they stood outside the Brevoort hotel, where she was staying." When Agnes came to a party for the Players at Christine's a few nights later, she also met Susan, who remarked on Agnes's striking resemblance to Louise. The romance between Gene and Agnes moved quickly; by January he had convinced her to go with him to Provincetown, since the battles being waged at the theatre were distracting him from writing, and the death from a heroin overdose of his good friend Louis Holladay, Polly's brother, was a shadow he wished to escape. After spending the winter together in a small studio that John Francis arranged for them, they got married on April 12, two days before Susan and jig's anniversary-dates the two couples would celebrate jointly over the next few years. By the summer Agnes and Gene had taken up residence in Francis's Flats, across Commercial Street near Susan and Jig's home.

During the summer of 1918 Gene got into the habit of visiting Susan each day immediately after both had finished their morning's work. The visits, to which Agnes was not invited, made the young bride grumpy and quiet when Gene would finally return "having stayed in that quiet restful house for too long." Gene was thirty, Susan forty-two, but that did not quiet Agnes. Agnes was aware of the soothing quality Susan exuded, her "feminine inner spirit, a fire, a sensitiveness that showed in her fine brown eyes and in the way that she used her hands and spoke." She knew of "many men who found her conversation simulating and helpful," since she could discuss "everything that was going on in the world - economics, the rights of mankind, the theatre, writing, people - and she was able to talk of them when necessary with charm and interest." Agnes, in comparison, felt herself far inferior: unworldly and inarticulate. She was then supporting Gene with her writing, mostly romance potboilers like "Ooh La La!"'; Susan wrote for Harper's. Agnes also knew it was always Susan, not Jig, whom Gene sought out for a talk. Whenever he wrote to the pair, he would invariably address the letter to Susan; his queries about his work and the Players were taken up with her. The critic Travis Bogard describes what O'Neill generally sought in friendships: "In a woman, performance of the functions of wife, mother, mistress, and chatelaine were sought; in a man, a combination of editorial solicitude, listening ability, financial acumen, and a producer's willingness to serve the demands of the artist were essential."' Susan was unique among O'Neill's relationships; all those qualities sought in men, he found in her, plus the decidedly feminine aura she radiated, which Agnes recognized. They talked about their work, read each other's finished manuscripts, and assisted each other whenever possible. She was the only playwright with whom he forged such a close personal and professional relationship.

(11) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

After a first night there would be a party in our club-room over the theatre. We were very poor at times, but never so poor we couldn't have wine for these parties. It was important we drink together, for thus were wounds healed, and we became one again, impulse and courage as if they had never been threatened. We had said hard things to one another in the drive of the last rehearsals, the strain of opening night. Now I might see Jig's arm around a neck he had threatened to wring. "Jig, you are getting drunk," some one would say. "It is for the good of the Provincetown Players," he would explain. "I am always ready to sacrifice myself to a cause." When the wine began to show the bottom of the bowl," Give it all to me," Jig would propose, "and I guarantee to intoxicate all the rest of you." He glowed at these parties. Things which years before had lain lonely in his mind flowed into a happy convivial hour, and dawn might find him eloquently espousing the cause of the elephant as over the lion, perhaps closing with a blaze of prophecy of a world in which men did not tear each other as lions tore, but where the strongest was he who did not feed upon his brother.

(12) J. Ellen Gainor, Susan Glaspell in Context (2001)

Widely regarded as the most tightly structured and thematically compelling of Glaspell's dramas, Trifles has been repeatedly anthologized and produced, standing as an exemplar of the one-act play form in numerous studies of the genre. Early reviews of the play glimpsed the radical possibilities liberated by Glaspell's method. Heywood Broun, who would soon become a strong supporter of the Provincetown players, first developed his positive opinion of Glaspell's writing when he saw the November 1916 production of Trifles by the Washington Square Players....

Broun's review synthesizes Glaspell's interweaving of gender roles and the detection process. He grasps the empathic process central to the women's growing understanding of Minnie and her presumed actions. Arthur Hornblow, the critic for Theatre Magazine, praised the production more succinctly as "an ingenious Study in feminine ability at inductive and deductive analysis by which two women through trifles bring out the motive for a murder". These reviews point to the dramaturgy. Her vivid use of offstage characters in Trifles will become a hallmark of her playwriting, recurring in Bernice, Inheritors, and Alison's House, among others. Mysteries and the process of deduction also recur throughout her plays, making Trifles both a representative work and one that adumbrates the themes and methods of many of her subsequent drarnas. Moreover, with Trifles she develops her technique of conscious manipulation of audiences' perspectives, so that they can see as she has done, which then allows her feminist and other progressive political views to come to the fore.

(13) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

Few Americans, I think, felt the war from so profound a tragic sense. "Feeling about life (its immensity, its vast antiquity, its minute complexity) and love, which is the farthest point from death that living things attain in their vibration between life and death."

He spoke often of what Nietzsche had said: "All nations claim to be armed for self-defence. Then let Germany, the strongest, disarm." He coveted for his own country that gesture Germany had not made.

Later, in notes for a play, he writes: " Statesman with vision of the surprising safety of disarmament. Grandeur of it. Profound courage of it. The strength of Christ."

He was thrilled by "Too proud to fight," and saw a great drama in The Rise and Fall of President Wilson.

Only once did he feel like going into the war himself, when Germany went on into Russia after Russia had stopped. In war politics he felt as true many things which have since been disclosed. His ardour through those years went to Russia. When the draft included the men of his age he wanted to state his refusal. I urged delay, stressing his own idea of keeping burning, to the measure we could, the light of creative imagination. My fears were for where his intensity might take him, once that fight were begun. But he wrote on the questionnaire he returned : " I will not go into Russia to fight or police Russian working-men."

He had remained a Socialist, but political interests had become less personal, absorbed in the creation of his own community. " Aridity, a dryness, about generalizations such as the great generalization of Socialism, unless these are given body by fresh and ever fresh facts. A generalization is like an organism. In order to remain living it must be fed with particulars, must eliminate waste.

"Unless the Socialist movement is going to make room in itself for a culture as broad and imaginative as any aristocratic culture, it would be better for the world that it perish from the earth."

(14) George Jig Cook, Provincetown Theatre Group (1919)

Three years ago, writing for the Provincetown Players, anticipating the forlornness of our hope to bring to birth in our commercial-minded country a theatre whose motive was spiritual, I made this promise: "We promise to let this theatre die rather than let it become another voice of mediocrity."

I am now forced to confess that our attempt to build up, by our own life and death, in this alien sea, a coral island of our own, has failed. The failure seems to be more our own than America's. Lacking the instinct of the coral-builders, in which we could have found the happiness of continuing ourselves toward perfection, we have developed little willingness to die for the thing we are building.

Our individual gifts and talents have sought their private perfection. We have not, as we hoped, created the beloved community of life-givers. Our richest, like our poorest, have desired most not to give life, but to have it given to them. We have valued creative energy less than its rewards-our sin against our Holy Ghost.

As a group we are not more but less than the great chaotic, unhappy community in whose dry heart I have vainly tried to create an oasis of living beauty.

"Since we have failed spiritually in the elemental things - failed to pull together - failed to do what any good football or baseball team or crew do as a matter of course with no word said - and since the result of this is mediocrity, we keep our promise: We give this theatre we love good death; the Provincetown Players end their story here.

Some happier gateway must let in the spirit which seems to be seeking to create a soul under the ribs of death in the American theatre.

(15) Susan Glaspell, The Road to the Temple (1926)

Jig was not well. I found him thinner when I returned from America, and he was thinner now than then. He would get tired of the food. In Agorgiani I urged to go to Athens and see a doctor. He would say he was going, but instead wanted to come to Kalania.

His thinner face, and his beard, made him look older. His moustache was black, like the eyebrows, but the beard, like his hair, was white. "Let it be wild here on Parnassos," he said, " then later we can see what it wants to do." He enjoyed the beard. I used to tease him about getting vain, for he would look at it and comb and form it this way and that. His white hair, too, would grow rather long. He looked like a man of the mountain ; more and more his eyes were the eyes of a seer.

(16) Floyd Dell wrote about Susan Glaspell and George Gig Cook in 1961.

My friend George Cook died in Greece in 1926. I had heard that he got with the shepherds, and was adored by them. Susan Glaspell has told the story of those days with great sympathy in The Road to the Temple. Susan Glaspell has said in her book that she has sometimes thought I would write a book about George. He was too close to me to be just to him. I loved him, and I would have had his life and death other than they were. I would have him die for Russia and the future, rather than Greece and the past. And if I wrote a book about George, that is what I should wish him to do.