Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was born in Staunton, Virginia, in 1856. Educated at Princeton, the University of Virginia and Johns Hopkins University, he became a professor at Princeton (1890-1902). He also published the book, History of the American People (1902)

After being elected Democratic Governor of New Jersey in 1911, Wilson became a national figure due to his progressive views on reform. The following year he was elected as the twenty-eighth President of the United States. Over the next few years he concentrated on anti-trust measures and on reorganizing the federal banking system.

On the outbreak of the First World War President Woodrow Wilson declared a policy of strict neutrality. Although the USA had strong ties with Britain, Wilson was concerned about the large number of people in the country who had been born in Germany and Austria. Other influential political leaders argued strongly in favour of the USA maintaining its isolationist policy. This included the pacifist pressure group, the American Union Against Militarism.

Some people argued that the USA should expand the size of its armed forces in case of war. General Leonard Wood, the former US Army Chief of Staff, formed the National Security League in December, 1914. Wood and his organisation called for universal military training and the introduction of conscription as a means of increasing the size of the US Army.

Opinion against Germany hardened after the sinking of the Lusitania. William J. Bryan, the pacifist Secretary of State, resigned and Wilson replaced him by the pro-Allied Robert Lansing. Wilson also announced an increase in the size of the US armed forces. However, in the 1916 Presidential election campaign, Woodrow Wilson stressed his policy of neutrality and his team used the slogan: "He Kept Us Out of the War".

Woodrow Wilson

On 31st January, 1917, Germany announced a new submarine offensive. Wilson responded by breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany. The publication of the Zimmerman Telegram, that suggested that Germany was willing to help Mexico regain territory in Texas and Arizona, intensified popular opinion against the Central Powers.

On 2nd April, Wilson asked for permission to go to war. This was approved in the Senate on 4th April by 82 votes to 6, and two days later, in the House of Representatives, by 373 to 50. Still avoiding alliances, war was declared against the German government (rather than its subjects). Wilson also insisted that the USA was an associated power rather than a member of the Allies.

On the 8th January, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson presented his Peace Programme to Congress. Compiled by a group of US foreign policy experts, the programme included fourteen different points. The first five points dealt with general principles: Point 1 renounced secret treaties; Point 2 dealt with freedom of the seas; Point 3 called for the removal of worldwide trade barriers; Point 4 advocated arms reductions and Point 5 suggested the international arbitration of all colonial disputes.

Points 6 to 13 were concerned with specific territorial problems including claims made by Russia, France and Italy. This part of Wilson's programme also raised issues such as the control of the Dardanelles and the claims for independence by the people living in areas controlled by the Central Powers.

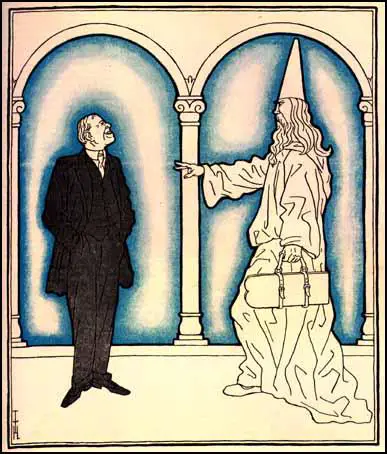

GOD: Woodrow Wilson, where are your 14 points?

WILSON: Don't get excited, Lord, we didn't keep your Ten Commandments either!

Thomas Heine, Simplicissimus, (17th June, 1919)

All the major countries involved in the First World War objected to certain points in Wilson's Peace Programme. However, when peace negotiations began in October, 1918, Wilson insisted that his Fourteen Points should serve as a basis for the signing of the Armistice.

Wilson attended the Paris Peace Conference and supported the Versailles Treaty. However, the Republicans now controlled the Senate, and they disliked the proposed League of Nations.

When the Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson began a nation-wide campaign to win support for the Paris Peace Agreement. While on this tour, he collapsed (26th September, 1919) and was an invalid for the last three and a half years of his life.

Thomas Woodrow Wilson died in 1924.

Primary Sources

(1) Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914)

There is no doubt, I think, that President Wilson and his party represent primarily small business in a war against the great interests. Socialists speak of his administration as a revolution within the bounds of capitalism. Wilson doesn't really fight the oppressions of property. He fights the evil done by large property-holders to small ones. The temper of his administration was revealed very clearly when the proposal was made to establish a Federal Trade Commission. It was suggested at once by leading spokesmen of the Democratic Party that corporations with a capital of less than a million dollars should be exempted from supervision. Is that because little corporations exploit labor or the consumer less? Not

a bit of it. It is because little corporations are in control of the political situation.

But there are certain obstacles to the working out of the New Freedom. First of all, there was a suspicion in Wilson's mind, even during the campaign, that the tendency to large organization was too powerful to be stopped by legislation. So he left open a way of escape from the literal achievement of what the New Freedom seemed to threaten. "I am for big business' he said, "and I am against the trusts." That is a very subtle distinction, so subtle, I suspect, that no human legislation will ever be able to make it. The distinction is this: big business is a business that has survived competition; a trust is an arrangement to do away with competition. But when competition is done away with, who is the Solomon wise enough to know whether the result was accomplished by superior efficiency or by agreement among the competitors or by both?

The big trusts have undoubtedly been built up in part by superior business ability, and by successful competition, but also by ruthless competition, by underground arrangements, by an intricate series of facts which no earthly tribunal will ever be able to disentangle. And why should it try? These great combinations are here. What interests us is not their history but their future. The point is whether you are going to split them up, and if so into how many parts. Once split, are they to be kept from coming together again? Are you determined to prevent men who could cooperate from cooperating? Wilson seems to imply that a big business which has survived competition is to be let alone, and the trusts attacked. But as there is no real way of distinguishing between them, he leaves the question just where he found it: he must choose between the large organization of business and the small.

(2) Woodrow Wilson, speech (22nd January, 1917)

No covenant of cooperative peace that does not include the peoples of the New World can suffice to keep the future safe against war; and yet there is only one sort of peace that the peoples of America could join in guaranteeing. The elements of that peace must be elements that engage the confidence and satisfy the principles of the American governments, elements consistent with their political faith and with the practical convictions which the peoples of America have once for all embraced and undertaken to defend.

I do not mean to say that any American government would throw any obstacle in the way of any terms of peace the governments now at war might agree upon or seek to upset them when made, whatever they might be. I only take it for granted that mere terms of peace between the belligerents will not satisfy even the belligerents themselves. Mere agreements may not make peace secure. It will be absolutely necessary that a force be created as a guarantor of the permanency of the settlement so much greater than the force of any nation now engaged, or any alliance hitherto formed or projected, that no nation, no probable combination of nations, could face or withstand it. If the peace presently to be made is to endure, it must be a peace made secure by the organized major force of mankind.

The terms of the immediate peace agreed upon will determine whether it is a peace for which such a guarantee can be secured. The question upon which the whole future peace and policy of the world depends is this: Is the present war a struggle for a just and secure peace, or only for a new balance of power? If it be only a struggle for a new balance of power, who will guarantee, who can guarantee the stable equilibrium of the new arrangement? Only a tranquil Europe can be a stable Europe. There must be, not a balance of power but a community of power; not organized rivalries but an organized, common peace.

Fortunately we have received very explicit assurances on this point. The statesmen of both of the groups of nations now arrayed against one another have said, in terms that could not be misinterpreted, that it was no part of the purpose they had in mind to crush their antagonists. But the implications of these assurances may not be equally clear to all - may not be the same on both sides of the water. I think it will be serviceable if I attempt to set forth what we understand them to be.

They imply, first of all, that it must be a peace without victory. It is not pleasant to say this. I beg that I may be permitted to put my own interpretation upon it and that it may be understood that no other interpretation was in my thought. I am seeking only to face realities and to face them without soft concealments. Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser, a victor's terms imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently but only as upon quicksand. Only a peace between equals can last. Only a peace the very principle of which is equality and a common participation in a common benefit. The right state of mind, the right feeling between nations, is as necessary for a lasting peace as is the just settlement of vexed questions of territory or of racial and national allegiance.

The equality of nations upon which peace must be founded if it is to last must be an equality of rights; the guarantees exchanged must neither recognize nor imply a difference between big nations and small, between those that are powerful and those that are weak. Right must be based upon the common strength, not upon the individual strength, of the nations upon whose concert peace will depend. Equality of territory or of resources there of course cannot be; nor any other sort of equality not gained in the ordinary peaceful and legitimate development of the peoples them- selves. But no one asks or expects anything more than an equality of rights. Mankind is looking now for freedom of life, not for equipoises of power.

(3) Elihu Root, speech (25th January, 1917)

The President has recently made a speech in the Senate, which we have all been reading, and I wish you to observe that the only way he sees out of the war that is devastating Europe is by preparation for war. There is much noble idealism in that speech of the President. With its purpose I fully sympathize. The kind of peace he describes is the peace that I long for. But the way he sees to preserve that peace is by preparation for war. Now, if some of our friends among the cornfields and the cotton fields and the mines and the citrus-fruit orchards will sit up and read this clause of the President's speech, telling how we may prevent further wars, they may have reason to wonder whether they have not forgotten something. Here it is:

"Mere agreements may not make peace secure. It will be absolutely necessary that a force be created as a guarantor of the permanency of the settlement so much greater than the force of any nation now engaged, or any alliance hitherto formed or projected, that no nation, no probable combinations of nations, could face or withstand it. If the peace presently to be made is to endure, it must be a peace made secure by the organized major force of mankind."

Now, I hope that paragraph means what I hope it does. I do not understand it as intended to commit the United States to enter into a convention or treaty with the other civilized countries of the world which will bind the United States to go to war on the continent of Europe or of Asia or in any other part of the world without the people of the United States having an opportunity at the time to say whether they will go to war or not. There would be serious difficulties, I think insurmountable obstacles, to the making of any such agreement. One is, that agreement or no agreement, when the time comes, the people of the United States will not go into any war, and nobody can get them into any war unless they then are in favor of fighting for something. And nothing can be so bad as to make a treaty and then break it. What I understand by it is that a convention shall be made by which all the civilized nations shall agree with all their power to stand behind the maintenance of the peace thus agreed upon; and, if that peace be infringed upon, then each nation shall determine what it is its duty to do under the obligation of that agreement toward the maintenance of that peace.

But observe that that is worthless, meaningless, unless the nations that enter into it keep the power behind it. It will be worthless agreement on our part if we have not a ship or a soldier that we can contribute to the war, if war there ought to be, for the maintenance of that peace. And it absolutely requires that we shall build up a force, a potential power of arms, commensurate with our size, our numbers, our wealth, our dignity, our part among the nations of the earth.

There is just one other sentence of this speech about which I wish to say a word, and that is the declaration that the peace must be a peace without victory. Now, I sympathize with that. But the peace that the President describes involves the absolute destruction and abandonment of the principles upon which this war was begun. It does not say "Serbia," it does not say "Belgium," but there the chosen head of the American people has declared the principles of the American democracy in unmistakable terms; has declared for the independence and equal rights of all small and weak nations; has declared for a Monroe Doctrine of the whole world precluding all nations from interfering with the independent control of its own affairs by every small nation, from taking away the territory of other nations, from attempting to exercise the coercion of superior power over other nations, for disarmament, for the reduction of these mighty armies and navies. And every word of that declaration, which I believe truly represents the conscience and judgment of the American people, denounces the sacrifice of Belgium and of Serbia and the principles upon which they were made.

(4) Woodrow Wilson, speech (1st February, 1917)

I have called the Congress into extraordinary session because there are serious, very serious, choices of policy to be made, and made immediately, which it was neither right nor constitutionally permissible that I should assume the responsibility of making.

On the 3rd of February last, I officially laid before you the extraordinary announcement of the Imperial German government that on and after the 1st day of February it was its purpose to put aside all restraints of law or of humanity and use its submarines to sink every vessel that sought to approach either the ports of Great Britain and Ireland or the western coasts of Europe or any of the ports controlled by the enemies of Germany within the Mediterranean.

That had seemed to be the object of the German submarine warfare earlier in the war, but since April of last year the Imperial government had somewhat restrained the commanders of its undersea craft in conformity with its promise then given to us that passenger boats should not be sunk and that due warning would be given to all other vessels which its submarines might seek to destroy, when no resistance was offered or escape attempted, and care taken that their crews were given at least a fair chance to save their lives in their open boats. The precautions taken were meager and haphazard enough, as was proved in distressing instance after instance in the progress of the cruel and unmanly business, but a certain degree of restraint was observed.

The new policy has swept every restriction aside. Vessels of every kind, whatever their flag, their character, their cargo, their destination, their errand, have been ruthlessly sent to the bottom without warning and without thought of help or mercy for those on board, the vessels of friendly neutrals along with those of belligerents. Even hospital ships and ships carrying relief to the sorely bereaved and stricken people of Belgium, though the latter were provided with safe conduct through the proscribed areas by the German government itself and were distinguished by unmistakable marks of identity, have been sunk with the same reckless lack of compassion or of principle.

International law had its origin in the attempt to set up some law which would be respected and observed upon the seas, where no nation had right of dominion and where lay the free highways of the world. By painful stage after stage has that law been built up, with meager enough results, indeed, after all was accomplished that could be accomplished, but always with a clear view, at least, of what the heart and conscience of mankind demanded.

This minimum of right the German government has swept aside under the plea of retaliation and necessity and because it had no weapons which it could use at sea except these which it is impossible to employ as it is employing them without throwing to the winds all scruples of humanity or of respect for the understandings that were supposed to underlie the intercourse of the world. I am not now thinking of the loss of property involved, immense and serious as that is, but only of the wanton and wholesale destruction of the lives of noncombatants, men, women, and children, engaged in pursuits which have always, even in the darkest periods of modern history, been deemed innocent and legitimate. Property can be paid for; the lives of peaceful and innocent people cannot be.

The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against man- kind. It is a war against all nations. American ships have been sunk, American lives taken in ways which it has stirred us very deeply to learn of; but the ships and people of other neutral and friendly nations have been sunk and overwhelmed in the waters in the same way. There has been no discrimination. The challenge is to all mankind.

With a profound sense of the solemn and even tragical character of the step I am taking and of the grave responsibilities which it involves, but in unhesitating obedience to what I deem my constitutional duty, I advise that the Congress declare the recent course of the Imperial German government to be in fact nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States; that it formally accept the status of belligerent which has thus been thrust upon it; and that it take immediate steps, not only to put the country in a more thorough state of defense but also to exert all its power and employ all its resources to bring the government of the German Empire to terms and end the war.

(5) Woodrow Wilson, speech (2nd April 1917)

The new policy, however, has swept every restriction aside. All vessels, irrespective of cargo and flag, have been sent to the bottom, without help and without mercy. Even hospital and relief ships, though provided with the Germans' safe conduct, were sunk with the same reckless lack of compassion or principle.

Germany's submarine warfare is no longer directed against belligerents, but against the whole world. All nations are involved in Germany's action. The challenge is to all mankind. Wanton, wholesale destruction has been effected against women and children while they have been engaged in pursuits which even in the darkest periods of modern history have been regarded as innocent and legitimate.

There is one choice I cannot make. I will not choose the path of submission, and suffer the most sacred rights of the nation and of the people to be ignored and violated.

With a profound sense of the solemn and even tragic character of the step I am taking, and of the grave responsibilities involved, but in unhesitating obedience to my constitutional duty, I advise Congress to declare that the recent course of the German Government is nothing less than war against the United States, and that the United States accept the status of a belligerent which has been thrust upon it, and will take immediate steps to put the country into a thorough state of defence, and to exert all her power and resource in bringing Germany to terms, and in ending the war.

(6) George Norris, speech (4th April, 1917)

While I am most emphatically and sincerely opposed to taking any step that will force our country into the useless and senseless war now being waged in Europe, yet, if this resolution passes, I shall not permit my feeling of opposition to its passage to interfere in any way with" my duty either as a senator or as a citizen in bringing success and victory to American arms. I am bitterly opposed to my country entering the war, but if, notwithstanding my opposition, we do enter it, all of my energy and all of my power will be behind our flag in carrying it on to victory.

The resolution now before the Senate is a declaration of war. Before taking this momentous step, and while standing on the brink of this terrible vortex, we ought to pause and calmly and judiciously consider the terrible consequences of the step we are about to take. We ought to consider likewise the route we have recently traveled and ascertain whether we have reached our present position in a way that is compatible with the neutral position which we claimed to occupy at the beginning and through the various stages of this unholy and unrighteous war.

No close student of recent history will deny that both Great Britain and Germany have, on numerous occasions since the beginning of the war, flagrantly violated in the most serious manner the rights of neutral vessels and neutral nations under existing international law, as recognized up to the beginning of this war by the civilized world.

The reason given by the President in asking Congress to declare war against Germany is that the German government has declared certain war zones, within which, by the use of submarines, she sinks, without notice, American ships and destroys American lives. The first war zone was declared by Great Britain. She gave us and the world notice of it on the 4th day of November, 1914. The zone became effective Nov. 5, 1914. This zone so declared by Great Britain covered the whole of the North Sea. The first German war zone was declared on the 4th day of February, 1915, just three months after the British war zone was declared. Germany gave fifteen days' notice of the establishment of her zone, which became effective on the 18th day of February, 1915. The German war zone covered the English Channel and the high seawaters around the British Isles.

It is unnecessary to cite authority to show that both of these orders declaring military zones were illegal and contrary to international law. It is sufficient to say that our government has officially declared both of them to be illegal and has officially protested against both of them. The only difference is that in the case of Germany we have persisted in our protest, while in the case of England we have submitted.

What was our duty as a government and what were our rights when we were confronted with these extraordinary orders declaring these military zones? First, we could have defied both of them and could have gone to war against both of these nations for this violation of international law and interference with our neutral rights. Second, we had the technical right to defy one and to acquiesce in the other. Third, we could, while denouncing them both as illegal, have acquiesced in them both and thus remained neutral with both sides, although not agreeing with either as to the righteousness of their respective orders. We could have said to American shipowners that, while these orders are both contrary to international law and are both unjust, we do not believe that the provocation is sufficient to cause us to go to war for the defense of our rights as a neutral nation, and, therefore, American ships and American citizens will go into these zones at their own peril and risk.

Fourth, we might have declared an embargo against the shipping from American ports of any merchandise to either one of these governments that persisted in maintaining its military zone. We might have refused to permit the sailing of any ship from any American port to either of these military zones. In my judgment, if we had pursued this course, the zones would have been of short duration. England would have been compelled to take her mines out of the North Sea in order to get any supplies from our country. When her mines were taken out of the North Sea then the German ports upon the North Sea would have been accessible to American shipping and Germany would have been compelled to cease her submarine warfare in order to get any supplies from our nation into German North Sea ports.

There are a great many American citizens who feel that we owe it as a duty to humanity to take part in this war. Many instances of cruelty and inhumanity can be found on both sides. Men are often biased in their judgment on account of their sympathy and their interests. To my mind, what we ought to have maintained from the beginning was the strictest neutrality. If we had done this, I do not believe we would have been on the verge of war at the present time. We had a right as a nation, if we desired, to cease at any time to be neutral. We had a technical right to respect the English war zone and to disregard the German war zone, but we could not do that and be neutral.

(7) Robert La Follette, speech (4th April, 1917)

If we are to enter upon this war in the manner the President demands, let us throw pretense to the winds, let us be honest, let us admit that this is a ruthless war against not only Germany's Army and her Navy but against her civilian population as well, and frankly state that the purpose of Germany's hereditary European enemies has become our purpose.

Again, the President says "we are about to accept the gage of battle with this natural foe of liberty and shall, if necessary, spend the whole force of the nation to check and nullify its pretensions and its power." That much, at least, is clear; that program is definite. The whole force and power of this nation, if necessary, is to be used to bring victory to the Entente Allies, and to us as their ally in this war. Remember, that not yet has the "whole force" of one of the warring nations been used.

Countless millions are suffering from want and privation; countless other millions are dead and rotting on foreign battlefields; countless other millions are crippled and maimed, blinded, and dismembered; upon all and upon their children's children for generations to come has been laid a burden of debt which must be worked out in poverty and suffering, but the "whole force" of no one of the warring nations has yet been expended; but our "whole force" shall be expended, so says the President. We are pledged by the President, so far as he can pledge us, to make this fair, free, and happy land of ours the same shambles and bottomless pit of horror that we see in Europe today.

Just a word of comment more upon one of the points in the President's address. He says that this is a war "for the things which we have always carried nearest to our hearts - for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own government." In many places throughout the address is this exalted sentiment given expression.

It is a sentiment peculiarly calculated to appeal to American hearts and, when accompanied by acts consistent with it, is certain to receive our support; but in this same connection, and strangely enough, the President says that we have become convinced that the German government as it now exists - "Prussian autocracy" he calls it - can never again maintain friendly relations with us. His expression is that "Prussian autocracy was not and could never be our friend," and repeatedly throughout the address the suggestion is made that if the German people would overturn their government, it would probably be the way to peace. So true is this that the dispatches from London all hailed the message of the President as sounding the death knell of Germany's government.

But the President proposes alliance with Great Britain, which, however liberty-loving its people, is a hereditary monarchy, with a hereditary ruler, with a hereditary House of Lords, with a hereditary landed system, with a limited and restricted suffrage for one class and a multiplied suffrage power for another, and with grinding industrial conditions for all the wageworkers. The President has not suggested that we make our support of Great Britain conditional to her granting home rule to Ireland, or Egypt, or India. We rejoice in the establishment of a democracy in Russia, but it will hardly be contended that if Russia was still an autocratic government, we would not be asked to enter this alliance with her just the same.

(8) Woodrow Wilson, Fourteen Points (October 1918)

What we demand in this war, therefore, is nothing peculiar to ourselves. It is that the world be made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair dealings by the other peoples of the world, as against force and selfish aggression. All the peoples of the world are in effect partners in this interest, and for our own part we see very clearly that unless justice be done to others it will not be done to us.

The program of the world's peace, therefore, is our program, and that program, the only possible program, as we see it, is this:

I. Open covenants of peace, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind, but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

II. Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

III. The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

IV. Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.

V. A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the Government whose title is to be determined.

VI. The evacuation of all Russian territory and such a settlement of all questions affecting Russia as will secure the best and freest co-operation of the other nations of the world in obtaining for her an unhampered and unembarrassed opportunity for the independent determination of her own political development and national policy, and assure her of a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and, more than a welcome, assistance also of every kind that she may need and may herself desire.

VII. Belgium, the whole world will agree, must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations.

VIII. All French territory should be freed and the invaded portions restored, and the wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the matter of Alsace-Lorraine, which has unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years, should be righted, in order that peace may once more be made secure in the interest of all.

IX. A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.

X. The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity of autonomous development.

XI. Rumania, Serbia, and Montenegro should be evacuated; occupied territories restored; Serbia accorded free and secure access to the sea; and the relations of the several Balkan States to one another determined by friendly counsel along historically established lines of allegiance and nationality; and international guarantees of the political and economic independence and territorial integrity of the several Balkan States should be entered into.

XII. The Turkish portions of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development, and the Dardanelles should be permanently opened as a free passage to the ships and commerce of all nations under international guarantees.

XIII. An independent Polish State should be erected which would include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which would be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

XIV. A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

(9) Woodrow Wilson, speech on the League of Nations (8th September, 1919)

For the first time in history the counsels of mankind are to be drawn together and concerted for the purpose of defending the rights and improving the conditions of working people - men, women, and children - all over the world. Such a thing as that was never dreamed of before, and what you are asked to discuss in discussing the League of Nations is the matter of seeing that this thing is not interfered with. There is no other way to do it than by a universal league of nations, and what is proposed is a universal league of nations.

Only two nations are for the time being left out. One of them is Germany, because we did not think that Germany was ready to come in, because we felt that she ought to go through a period of probation. She says that she made a mistake. We now want her to prove it by not trying it again. She says that she has abolished all the old forms of government by which little secret councils of men, sitting nobody knew exactly where, determined the fortunes of that great nation and, incidentally, tried to determine the fortunes of mankind; but we want her to prove that her constitution is changed and that it is going to stay changed; and then who can, after those proofs are produced, say "No" to a great people, 60 million strong, if they want to come in on equal terms with the rest of us and do justice in international affairs?

I want to say that I did not find any of my colleagues in Paris disinclined to do justice to Germany. But I hear that this treaty is very hard on Germany. When an individual has committed a criminal act, the punishment is hard, but the punishment is not unjust. This nation permitted itself, through unscrupulous governors to commit a criminal act against mankind, and it is to undergo the punishment, not more than it can endure but up to the point where it can pay it must pay for the wrong that it has done.

But the things prescribed in this treaty will not be fully carried out if any one of the great influences that brought that result about is withheld from its consummation. Every great fighting nation in the world is on the list of those who are to constitute the League of Nations. I say every great nation, because America is going to be included among them, and the only choice my fellow citizens is whether we will go in now or come in later with Germany; whether we will go in as founders of this covenant of freedom or go in as those who are admitted after they have made a mistake and repented.

(10) David Lloyd George, The Truth About the Peace Treaties (1938)

There never was a greater contrast, mental or spiritual, than that which existed between these two notable men. Wilson with his high but narrow brow, his fine head with its elevated crown and his dreamy but untrustful eye - the make-up of the idealist who is also something of an egoist; Clemenceau, with a powerful head and the square brow of the logician - the head conspicuously flat topped, with no upper storey in which to lodge the humanities, the ever vigilant and fierce eye of the animal who has hunted and been hunted all his life. The idealist amused him so long as he did not insist on incorporating his dreams in a Treaty which Clemenceau had to sign.

It was part of the real joy of these Conferences to observe Clemenceau's attitude towards Wilson during the first five weeks of the Conference. He listened with eyes and ears lest Wilson should by a phrase commit the Conference to some proposition which weakened the settlement from the French standpoint. If Wilson ended his allocution without doing any perceptible harm, Clemenceau's stern face temporarily relaxed, and he expressed his relief with a deep sigh. But if the President took a flight beyond the azure main, as he was occasionally inclined to do without regard to relevance, Clemenceau would open his great eyes in twinkling wonder, and turn them on me as much as to say: "Here he is off again!"

(11) Edward M. House, diary (29th June, 1919)

June 29, 1919: I am leaving Paris, after eight fateful months, with conflicting emotions. Looking at the conference in retrospect there is much to approve and much to regret. It is easy to say what should have been done, but more difficult to have found a way for doing it.

The bitterness engendered by the war, the hopes raised high in many quarters because of victory, the character of the men having the dominant voices in the making of the Treaty, all had their influence for good or for evil, and were to be reckoned with.

How splendid it would have been had we blazed a new and better trail! However, it is to be doubted whether this could have been done, even if those in authority had so decreed, for the peoples back of them had to be reckoned with. It may be that Wilson might have had the power and influence if he had remained in Washington and kept clear of the Conference. When he stepped from his lofty pedestal and wrangled with representatives of other states upon equal terms, he became as common clay.

To those who are saying that the Treaty is bad and should never have been made and that it will involve Europe in infinite difficulties in its enforcement, I feel like admitting it. But I would also say in reply that empires cannot be shattered and new states raised upon their ruins without disturbance. To create new boundaries is always to create new troubles. The one follows the other. While I should have preferred a different peace, I doubt whether it could have been made, for the ingredients for such a peace as I would have had were lacking at Paris

The same forces that have been at work in the making of this peace would be at work to hinder the enforcement of a different kind of peace, and no one can say with certitude that anything better than has been done could be done at this time. We have had to deal with a situation pregnant with difficulties and one which could be met only by an unselfish and idealistic spirit, which was almost wholly absent and which was too much to expect of men come together at such a time and for such a purpose.

And yet I wish we had taken the other road, even if it were less smooth, both now and afterward, than the one we took. We would at least have gone in the right direction and if those who follow us had made it impossible to go the full length of the journey planned, the responsibility would have rested with them and not with us.

(12) Harold Nicholson, Peacemaking 1919 (1933)

I have also indicated the acute difficulty experienced by the negotiators in Paris in reconciling the excited expectations of their own democracies with the calmer considerations of durable peacemaking. Such contrast can be grouped together under what will forever be the main problem of democratic diplomacy; the problem, that is, of adjusting the emotions of the masses to the thoughts of the rulers.

What the statesman thinks today, the masses may feel tomorrow. The attempt rapidly to bridge the gulf between mass-emotion and expert reason leads, at its worst, to actual falsity, and, at its best to grave imprecision.

The contrast took the form - the unnecessary and perplexing form - of a contrast not only between the new diplomacy and the old, but between the new world and the old, between Europe and America.

On the one hand you had Wilsonism - a doctrine which was very easy to state and very difficult to apply. Mr. Wilson had not invented any new political philosophy, or discovered any doctrine which had not been dreamed of, and appreciated, for many hundred years. The one thing which rendered Wilsonism so passionately interesting at the moment was the fact that this centennial dream was suddenly backed by the overwhelming resources of the strongest Power in the world. Here was a man who represented the greatest physical force which had ever existed and who had pledged himself openly to the most ambitious moral theory which any statesman had ever pronounced.

On the other hand you had Europe, the product of a wholly different civilisation, the inheritor of unalterable circumstances, the possessor of longer and more practical experience. Through the centuries of conflict the Europeans had come to learn that war is in almost every case contrived with the expectation of victory, and that such an expectation is diminished under a system of balanced forces which renders victory difficult, if not uncertain. Backed by the assurance of America's immediate and unquestioned support, the statesmen of Europe might possibly have jettisoned their old security for the wider security offered them by the theories of Woodrow Wilson.