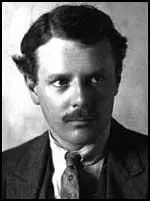

Harold Nicolson

Harold Nicolson, the third son of Arthur Nicolson, first Baron Carnock, and his wife, Mary Katharine Rowan was born in Teheran on 21st November, 1886. His father was a diplomat and his childhood was spent in Turkey, Spain, Morocco and Russia.

In 1895, he was sent away to attend The Grange, a preparatory school near Folkestone. In 1900 he went to Wellington College. Although he disliked his public school education, he was greatly influenced by Bertram Pollock, who later became Bishop of Norwich. As a result of Pollock's teaching he learned to love literature and the classics.

Nicolson moved on to Balliol College in 1904. According to his biographer, Thomas G. Otte: "After the conventional dullness of Wellington, Nicolson flourished in Balliol's liberal and cerebrally stimulating climate, but left Oxford in 1907 with only a pass degree, having obtained a third in classical honour moderations the previous year."

In October 1909, he passed second in the competitive entrance examination for the diplomatic service. He spent his early years in the service as an attaché at Madrid. In June 1910 Harold met Vita Sackville-West for the first time. Harold visited Vita in Monte Carlo in January 1911: Vita recorded: "He was as gay and clever as ever, and I loved his brain and his youth, and was flattered at his liking for me. He came to Knole a good deal that autumn and winter, and people began to tell me he was in love with me, which I didn't believe was true, but wished that I could believe it. I wasn't in love with him then - there was Rosamund - but I did like him better than anyone, as a companion and playfellow, and for his brain and his delicious disposition."

Vita Sackville-West was a lesbian and at this time was having affairs with Violet Keppel and Rosamund Grosvenor. In January 1912 Nicolson proposed to Vita. She refused him but under pressure from her mother, Victoria Sackville-West, Vita agreed to become engaged. As a result of the engagement, her mother gave her an allowance of £2,500 a year, of which the capital was to become hers on her mother's death. Later that month he was appointed as third secretary at Constantinople.

Harold Nicholson became concerned about Vita's relationship with Rosamund Grosvenor. He was puzzled by Rosamund's subservient attitude to Vita. He mentioned this in a letter to Vita, who replied: "It is a pity and rather tiresome. But doesn't everyone want one subservient person in your life? I've got mine in her. Who is yours? Certainly not me!" Vita later wrote in her autobiography: "It did not seem wrong to be... engaged to Harold, and at the same time so much in love with Rosamund... Our relationship (with Harold Nicholson) was so fresh, so intellectual, so unphysical, that I never thought of him in that aspect at all.... Some were born to be lovers, others to be husbands, he belongs to the latter category."

Rosamund Grosvenor became jealous of Vita's relationships with Harold Nicholson, Violet Keppel and Muriel Clark-Kerr, the sister of Archibald Clark-Kerr. Rosamund wrote to Vita: "Oh my sweet you do know don't you. Nothing can ever make me love you less whatever happens, and I really think you have taken all my love already as there seems very little left." After one love-making session she wrote: "My sweet darling... I do miss you darling one and I want to feel your soft cool face coming out of that mass of pussy fur like I did last night."

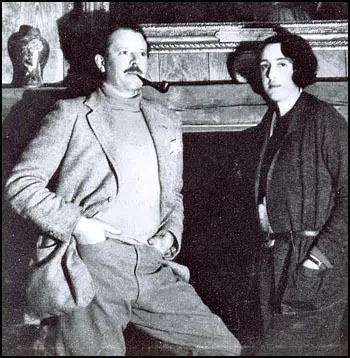

Despite having several affairs with women, Vita Sackville-West married Harold Nicholson on 1st October, 1913 at Knole House, the family home. They spent their honeymoon in Spain and Italy. Their first son, Lionel Benedict Nicolson, was born on 6th August 1914. They lived both in London and at Long Barn, a house near Sevenoaks. A second son was stillborn in 1915, and their last child, Nigel Nicolson, was born in London in 1917.

During the First World War Nicolson worked for the Foreign Office. Along with Mark Sykes and Leo Amery, he was one of the chief draftsmen of the Balfour Declaration, which committed Britain to supporting a Jewish homeland in Palestine. As a junior Foreign Office official Nicolson attended the Versailles Peace Conference after the Armistice. After the conference he was appointed private secretary to Eric Drummond, the first secretary-general of the infant League of Nations.

In April 1918 Vita Sackville-West resumed her affair with Violet Keppel. Vita later wrote: "She lay on the sofa, I sat plunged in the armchair; she took my hands, and parted my fingers to count the points as she told me why she loved me... She pulled me down until I kissed her - I had not done so for many years." The lovers travelled around Europe and collaborated on a novel, Challenge (1923), that was published in America but banned in Britain.

Violet Keppel came under pressure from her mother, Alice Keppel, to bring an end to her affair with Vita Sackville-West. Reluctantly she married Denys Robert Trefusis, an officer in the Royal Horse Guards, on 16th June 1919. She did so on the understanding that the marriage would remain unconsummated, and she was still resolved to live with Vita. They resumed their affair just a few days after the wedding. The women moved to France in February 1920. However, Harold Nicholson followed them and eventually persuaded Vita to return to the family home.

T. J. Hochstrasser points out: "However, this crisis in fact proved eventually to be the catalyst for Nicolson and Sackville-West to restructure their marriage satisfactorily so that they could both pursue a series of relationships through which they could fulfil their essentially homosexual identity while retaining a secure basis of companionship and affection."

Harold's son, Nigel Nicolson, later wrote in his book, Portrait of a Marriage (1973): "When she (Vita) married Harold, she assumed that marriage was love by other means, and for a time it worked. The very existence of myself and my brother is proof of it, and there is ample evidence in the letters and diaries that for the first few years of their marriage they were sexually compatible. After 1917 it gradually became clear that their mutual enjoyment was on the wane.... Harold had a series of relationships with men who were his intellectual equals, but the physical element in them was very secondary. He was never a passionate lover. To him sex was as incidental, and about as pleasurable, as a quick visit to a picture-gallery between trains. His a-sexual love for Vita in later life was balanced by affection for his men friends, by some of whom he was temporarily, but never helplessly, attracted. There was no moment in his life when love for a young man became such an obsession to him that it interfered with his work, and he had no affairs faintly comparable to Vita's. Their behaviour in this respect was a reflection of their very different personalities. His life was too well regulated to be affected by affairs of the heart, while she always allowed herself to be swept away."

Nicolson became the private secretary of Lord Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, at several important conferences and was Britain's representative on a number of subcommittees. In 1925 he was transferred to Teheran as counsellor of legation. Although busy with diplomatic work he still found time to write several literary biographies: Tennyson (1923), Byron: the Last Journey (1924), and Swinburne (1926). In September 1929 Nicolson resigned from the diplomatic service in order to concentrate on his writing career.

In 1930, Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West left Long Barn and purchased Sissinghurst Castle, which they set about restoring and developing into the setting for a large-scale garden. As T. J. Hochstrasser has pointed out: "Sissinghurst... the sketchy remains of a Kentish Elizabethan mansion, which they set about restoring and developing into the setting for a large-scale garden: this was a joint project where the principles of design were contributed by Nicolson and the planting schemes and maintenance by Sackville-West."

In 1931 Nicolson joined Sir Oswald Mosley and his recently formed New Party. He edited the party newspaper, Action, and stood unsuccessfully for Parliament in the 1931 General Election. Nicolson ceased to support Mosley when he formed the British Union of Fascists in 1932.

Nicolson entered the House of Commons as National Labour MP for West Leicester in the 1935 General Election. Nicolson served as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Information in the coalition government formed by Winston Churchill in 1940. Nicolson was defeated in the 1945 General Election.

Books written by Nicolson include: Peacemaking 1919 (1933), Curzon (1934), The Congress of Vienna (1946), King George V (1952), Good Behaviour (1956), The Age of Reason (1961) and Kings, Courts and Monarchy. His Diaries and Letters (1968), edited by his son, Nigel Nicolson, provide an interesting insight into political life between the two world wars.

Harold Nicolson died on 1st May 1968, following a stroke, and was buried at Sissinghurst Church.

Primary Sources

(1) Vita Sackville-West, Autobiography (1920)

It did not seem wrong to be... engaged to Harold, and at the same time so much in love with Rosamund Grosvenor... Our relationship (with Harold Nicholson) was so fresh, so intellectual, so unphysical, that I never thought of him in that aspect at all.... Some were born to be lovers, others to be husbands, he belongs to the latter category.... It was passion that used to make my head swim sometimes, even in the daytime, but we never made love.

(2) Harold Nicolson, Peacemaking 1919 (1933)

I have also indicated the acute difficulty experienced by the negotiators in Paris in reconciling the excited expectations of their own democracies with the calmer considerations of durable peacemaking. Such contrast can be grouped together under what will forever be the main problem of democratic diplomacy; the problem, that is, of adjusting the emotions of the masses to the thoughts of the rulers.

What the statesman thinks today, the masses may feel tomorrow. The attempt rapidly to bridge the gulf between mass-emotion and expert reason leads, at its worst, to actual falsity, and, at its best to grave imprecision. The contrast took the form - the unnecessary and perplexing form - of a contrast not only between the new diplomacy and the old, but between the new world and the old, between Europe and America. On the one hand you had Wilsonism - a doctrine which was very easy to state and very difficult to apply. Mr. Wilson had not invented any new political philosophy, or discovered any doctrine which had not been dreamed of, and appreciated, for many hundred years. The one thing which rendered Wilsonism so passionately interesting at the moment was the fact that this centennial dream was suddenly backed by the overwhelming resources of the strongest Power in the world. Here was a man who represented the greatest physical force which had ever existed and who had pledged himself openly to the most ambitious moral theory which any statesman had ever pronounced. On the other hand you had Europe, the product of a wholly different civilisation, the inheritor of unalterable circumstances, the possessor of longer and more practical experience. Through the centuries of conflict the Europeans had come to learn that war is in almost every case contrived with the expectation of victory, and that such an expectation is diminished under a system of balanced forces which renders victory difficult, if not uncertain. Backed by the assurance of America's immediate and unquestioned support, the statesmen of Europe might possibly have jettisoned their old security for the wider security offered them by the theories of Woodrow Wilson.

(3) Vita Sackville-West, Autobiography (1920)

Harold came back from Madrid at the end of that summer (1911). He had been very ill out there, and I remember him as rather a pathetic figure wrapped up in an Ulster on a warm summer day, who was able to walk slowly round the garden with me. All that time while I was "out" is extremely dim to me, very largely I think, owing to the fact that I was living a kind of false life that left no impression upon me. Even my liaison with Rosamund was, in a sense, superficial. I mean that it was almost exclusively physical, as, to be frank, she always bored me as a companion. I was very fond of her, however; she had a sweet nature. But she was quite stupid.

Harold wasn't. He was as gay and clever as ever, and I loved his brain and his youth, and was flattered at his liking for me. He came to Knole a good deal that autumn and winter, and people began to tell me he was in love with me, which I didn't believe was true, but wished that I could believe it. I wasn't in love with him then - there was Rosamund - but I did like him better than anyone, as a companion and playfellow, and for his brain and his delicious disposition. I hoped that he would propose to me before he went away to Constantinople, but felt diffident and sceptical about it.

(4) Nigel Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage (1973)

Her mother's fastidiousness and her father's reluctance to discuss any intimate subject with her deepened her sexual isolation. With Rosamund she tumbled into love, and bed, with a sort of innocence. At first it meant little more to her than cuddling a favourite dog or rabbit, and later she regarded the affair as more naughty than perverted, and took great pains to conceal it from her parents and Harold, fearing that exposure would mean the banishment of Rosamund. It was little more than that. She had no concept of any moral distinction between homosexual and heterosexual love, thinking of them both as "love" without qualification. When she married Harold, she assumed that marriage was love by other means, and for a time it worked.

The very existence of myself and my brother is proof of it, and there is ample evidence in the letters and diaries that for the first few years of their marriage they were sexually compatible. After 1917 it gradually became clear that their mutual enjoyment was on the wane. Lady Sackville refers in her diaries to frank conversations with Vita on the subject ("She remarks about Harold being so physically cold"). When I myself married, my father solemnly cautioned me that the physical side of marriage could not be expected to last more than a year or two, and once, in a broadcast, he said, "Being in love lasts but a short time - from three weeks to three years. It has little or nothing to do with the felicity of marriage."

Simultaneously, therefore, and without placing any great strain upon their love for each other, they began to seek pleasure with people of their own sex, and to Vita at least it seemed quite natural, for she was simply reverting to her other form of "love". Marriage and sex could be quite separate things....

She (Vita) didn't know how strong and dangerous such passion could be, until Violet replaced Rosamund. Of course she knew that "such a thing existed", but she did not give it a name, and felt no guilt about it. At the time of her marriage she may have been ignorant that men could feel for other men as she had felt for Rosamund, but when she had made this discovery in Harold himself, it did not come as a great shock to her, for she had the romantic notion that it was natural and salutary for "people" to love each other, and the desire to kiss and touch was simply the physical expression of affection, and it made no difference whether it was affection between people of the same sex or the opposite.

It was fortunate that both were made that way. If only one of them had been, their marriage would probably have collapsed. Violet did not destroy their physical union; she simply provided the alternative for which Vita was unconsciously seeking at the moment when her physical passion for Harold, and his for her, had begun to cool. In Harold's life at that time there was no male Violet, luckily for him, since his love for Vita might not have survived two rivals simultaneously. Before he met Vita he had been half-engaged to another girl, Eileen Wellesley. He was not driven to homosexuality by Vita's temporary desertion of him, because it had always been latent, but his loneliness may have encouraged this tendency to develop, since with his strong sense of duty (much stronger than Vita's) he felt it to be less treacherous to sleep with men in her absence than with other women. When he was left stranded in Paris, he once confessed to Vita that he was "spending his time with rather low people, the demi-monde", and this could have meant young men. When she returned to him, it certainly did. Lady Sackville noted in her diary, "Vita intends to be very platonic with Harold, who accepts it like a lamb.' They never shared a bedroom after that.

Harold had a series of relationships with men who were his intellectual equals, but the physical element in them was very secondary. He was never a passionate lover. To him sex was as incidental, and about as pleasurable, as a quick visit to a picture-gallery between trains. His a-sexual love for Vita in later life was balanced by affection for his men friends, by some of whom he was temporarily, but never helplessly, attracted. There was no moment in his life when love for a young man became such an obsession to him that it interfered with his work, and he had no affairs faintly comparable to Vita's. Their behaviour in this respect was a reflection of their very different personalities. His life was too well regulated to be affected by affairs of the heart, while she always allowed herself to be swept away.

(5) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (1st September, 1939)

Motor up ... to London. There are few signs of any undue activity beyond a few khaki figures at Staplehurst and some schoolboys filling sandbags at Maidstone. When we get near London we see a row of balloons hanging like black spots in the air. Go down to the House of Commons at 5.30. They have already darkened the building and lowered the lights... I dine at the Beefsteak (Club).... When I leave the Club, I am startled to find a perfectly black city. Nothing could be more dramatic or give one more of a shock than to leave the familiar Beefsteak and to find outside not the glitter of all the sky-signs, but a pall of black velvet.