British Union of Fascists

On 20th February, 1931, six Labour Party MPs, Oswald Mosley, Cynthia Mosley, John Strachey, Robert Forgan, Oliver Baldwin (the son of Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party) and William J. Brown, decided to resign from the party. William E. Allen, the Tory MP for West Belfast, and Cecil Dudgeon, the Liberal MP for Galloway, also agreed to join the New Party. However, Brown and Baldwin changed their minds and sat in the House of Commons as Independents and six months later rejoined the Labour Party. (1)

Other people who joined the New Party included Cyril Joad (Director of Propaganda), Harold Nicolson (editor of their journal, Action), Mary Richardson (former member of the Women's Social and Political Union), John Becket and Peter Dunsmore Howard (captain of the England national rugby union team). Other members included Allan Young and Jack Jones, both former member of the Labour Party, Charles Bentinck Budd, Jorian Jenks, Charles E. Hudson, John Sidney Crosland, Wilfred Risdon and James Lees-Milne, an architectural historian. (2)

During the 1931 General Election Mosley held large open-meetings all over England. James Lees-Milne, one of the New Party candidates, commented later: "He brooked no argument, would accept no advice. He had in him the stuff of which zealots are made. The posturing, the grimacing, the switching on and off of those gleaming teeth, and the overall swashbuckling... were more likely to appeal to Mayfair flappers than to sway indigent workers." (3) Mosley made it clear the the New Party had "purged the party of all associations with Socialism". (4)

The New Party fielded 25 candidates in the General Election. Cynthia Mosley refused to stand and her husband decided to make use of her personal following and stood instead of her at Stoke-on-Trent. All of its resources were concentrated in seats held by the Labour Party. Only a few weeks before the election, Mosley announced it was committed to the corporate state. Its newspaper, pointed out that though inspired by the Fascist movement it wanted British answers "framed to accord with the character and high experience of this race". It went on to argue the policies would be "within the framework of the Corporate State, we wish to give the fullest possible expansion to individual development and enjoyment". Finally it announced that it planned to form a special defence corps." (5)

In the 1931 General Election the New Party fielded 25 candidates. Mosley obtained 10,500 votes in Stoke but was bottom of the poll. Only two candidates, Mosley and Sellick Davies, standing in Merthyr Tydfil, saved their deposits. The total votes cast for the New Party were 36,377. This compared badly with the Communist Party of Great Britain, which managed 74,824 votes for 26 candidates. Ramsay MacDonald, and his National Government won 556 seats. Mosley told Nicolson that "we have been swept away in a hurricane of sentiment" and that "our time is yet to come". (6)

British Union of Fascists

In December, 1931, Harold Harmsworth, 1st Lord Rothermere, the press baron, whose newspapers had been especially hostile to the New Party during the election, had a meeting with Mosley. According to Mosley's son, Nicholas Mosley, Rothermere told him that he was prepared to put the Harmsworth press at his disposal if he succeeded in organising a disciplined Fascist movement from the remnants of the New Party. (7) The details of this meeting was recorded in his diary by Mosley's close friend, Harold Nicolson. (8)

It was very important to Rothermere that this new party would target working-class voters in order that it would help the fortunes of the Conservative Party. Cynthia Mosley disagreed with her husband's move to the right. According to Robert Skidelsky: "Cimmie (Cynthia) was frankly terrified of where his restlessness would lead him. She hated fascism and Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere, the press baron). She threatened to put a notice in The Times dissociating herself from Mosley's fascist tendencies. They bickered constantly in public, Cimmie emotional and confused, Mosley ponderously logical and heavily sarcastic." (9)

In January 1932, Oswald Mosley, William E. Allen and Harold Nicholson visited Italy to study fascism at first hand. Mosley met Benito Mussolini who he found "affable but unimpressive". Mussolini advised Mosley to "call himself a fascist, but not to try the military stunt in England". Nicholson claimed in his diary that Mosley was not put off by the way Mussolini had arrested his opponents and the censorship of Italian newspapers. "Mosley... cannot keep his mind off shock troops, the arrest of MacDonald and J. H. Thomas, their internment in the Isle of Wight and the roll of drums around Westminster. He is a romantic. That is a great failing." (10)

On his return to England, Oswald Mosley wrote an article in The Daily Mail about the achievements of Mussolini. "A visit to Mussolini... is typical of that new atmosphere. No time is wasted in the polite banalities which have so irked the younger generation in Britain when dealing with our elder statesmen.... Questions on all relevant and practical subjects are fired with the rapidity and precision of bullets from a machine gun; straight, lucid, unaffected exposition follows of his own views on subjects of mutual interest to him and to his visitor.... The great Italian represents the first emergence of the modern man to power; it is an interesting and instructive phenomenon. Englishmen who have long suffered from statesmanship in skirts can pay him no less, and need pay him no more, tribute than to say, Here at least is a man". (11)

Mosley now became convinced that the time was right to establish a fascist party. There had been fascist groups in the past. Miss Rotha Lintorn-Orman established the British Fascisti organization in 1923. She later said: "I saw the need for an organization of disinterested patriots, composed of all classes and all Christian creeds, who would be ready to serve their country in any emergency." Members of the British Fascists had been horrified by the Russian Revolution. However, they had gained inspiration from what Mussolini had done it Italy. (12)

Most members of the British Fascisti came from the right-wing of the Conservative Party. Early recruits included William Joyce, Maxwell Knight and Nesta Webster. Knight's work as Director of Intelligence for the British Fascists brought him to the attention of Vernon Kell, Director of the Home Section of the Secret Service Bureau. This government organization had responsibility of investigating espionage, sabotage and subversion in Britain and was also known as MI5. In 1925 Kell recruited Knight to work for the Secret Service Bureau and played a significant role in helping to defeat the General Strike in 1926. (13)

Arnold Leese, a retired veterinary surgeon, had founded the Imperial Fascist League (IFL) in 1929. He had a private army called the Fascist Legions, who never numbered more than three dozen, wore black shirts and breeches. The IFL defined fascism as the "patriotic revolt against democracy and a return to statesmanship" and planned to "impose a corporate state" on the country. It also believed that Jews should be banned from citizenship. The IFL enemies were Communism, Freemasonry and Jews. (14)

Mosley originally dismissed the Imperial Fascist League as "one of those crank little societies mad about the Jews". However, on 27th April 1932, Mosley arranged for Leese to speak to New Party members, on the subject of The Blindness of British Politics under Jew Money-Power. However, the two men did not get on well together. Leese refused all co-operation with Mosley, "believing him to be in the pay of the Jews". (15)

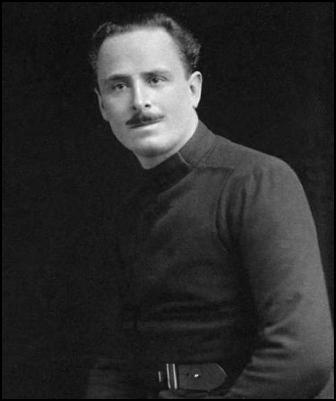

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was formally launched on 1st October, 1932. It originally had only 32 members and included several former members of the New Party: Cynthia Mosley, Robert Forgan, William E. Allen, John Beckett and William Joyce. Mosley told them: "We ask those who join us... to be prepared to sacrifice all, but to do so for no small or unworthy ends. We ask them to dedicate their lives to building in the country a movement of the modern age... In return we can only offer them the deep belief that they are fighting that a great land may live." (16)

Attempts were made to keep the names of individual members a secret but supporters of the organization included Charles Bentinck Budd, Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere), Norah Briscoe, Major General John Fuller, Jorian Jenks, Commander Charles E. Hudson, John Sidney Crosland, James Louis Crosland, Wing-Commander Louis Greig, A. K. Chesterton, David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), Unity Mitford, Diana Mitford, Patrick Boyle (8th Earl of Glasgow), Malcolm Campbell and Tommy Moran. Mosley refused to publish the names or numbers of members but the press estimated a maximum number of 35,000. (17)

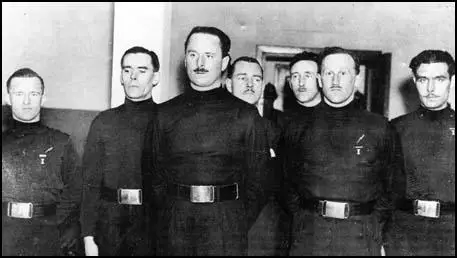

Mosley decided that members of the BUF should wear a uniform. The black shirt was to be the symbol of Fascism. According to Mosley the "black shirt was the outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace". The uniform enabled his stewards to recognise each other in a fight against those trying to disrupt BUF meetings. "In addition, the uniform was a symbol of authority, and as such his uniformed squads would not only be a rallying-point, but also a striking-force in any battle that might develop with the communists for the control of the State." (18)

Oswald Mosley Documentary

Mary Richardson was one of those who liked the idea of a uniform: "I was first attracted to the Blackshirts because I saw in them the courage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service, and the ability to serve which I had known in the suffrage movement". Mosley commented: "In the Blackshirt all men are the same, whether millionaire or on the dole. The barriers of class distinction and social differences are broken down by the Blackshirt within a Movement which aims at the creation of a classroom brotherhood marked only by functional differences." (19)

Mosley began to argue for the corporate state: "How can any international system, whether capitalist or Socialist, advance or even maintain the standard of life of our people? None can deny the truism that to sell we must find customers and, as foreign markets progressively close... the home customer becomes ever more the outlet of industry. But the home customer is simply the British people, on whose purchasing power our industry is ever more dependent. For the most part the purchasing power of the British people depends on the wages and salaries they are paid... Yet wages and salaries of the British people are held down far below the level which modern science, and the potential of production, could justify because their labour is subject to... undercutting competition... on both foreign and home markets.... The result is the tragic paradox of poverty and unemployment amid potential plenty.... Internationalism, in fact, robs the British people of the power to buy the goods that the British people produce." (20)

Cynthia Mosley remained a member of the British Union of Fascists but was not a strong believer in Fascism. She was also in bad health. Harold Nicolson wrote: "Cimmie (Cynthia) comes to see me. She has not been well. She faints. She even faints in bed. She talks about Tom (Oswald) and Fascismo. She really does care for the working-classes and loathes all forms of reaction." (21)

Cynthia, the mother of two children (Elisabeth and Nicholas), had a difficult pregnancy with a third child. Nicolson once again wrote about the situation: "Cimmie has been very ill. She has kidney trouble and they want to do a caesarean operation. Unfortunately the child is too young to survive and Climmie wants to hang on for a fortnight. Tom (Oswald) is faced with the awful dilemma of sacrificing his baby or his wife." (22)

Michael Mosley was born on 25th April 1932. After a long convalescence Cynthia's health gradually recovered. In April 1933 she agreed to accompany her husband to visit Benito Mussolini. They all appeared together on the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia, and made the fascist salute in one of the very rare occasions when she publicly showed any sympathy with fascism." (23).

On her return to London she was again taken ill and was rushed to hospital to have her appendix removed. The operation was successful but two days later, on 16th May, 1933, she died of peritonitis. Oswald Mosley was completely shattered by Cynthia's death but according to his friends it intensified his political beliefs and made him even more committed to fascism: "He now regards his movement as a memorial to Cimmie and is prepared willingly to die for it." (24)

In a speech made in March, 1933, Mosley outlined his Fascist beliefs: "The Fascist principle is private freedom and public service. That imposes upon us, in our public life, and in our attitude towards other men, a certain discipline and a certain restraint; but in our public life alone; and I should argue very strongly indeed that the only way to have private freedom was by a public organisation which brought some order out of the economic chaos which exists in the world today, and that such public organisation can only be secured by the methods of authority and of discipline which are inherent in Fascism." (25)

Mosley began to openly question democracy. He quoted approvingly the words of George Bernard Shaw: "What is the historical function of Parliament in this country? It is to prevent the Government from governing. It has never had any other purpose... Bit by bit it broke the feudal Monarchy; it broke the Church; and finally it even broke the country gentleman. Then, having broken everything that could govern the country, it left us at the mercy of our private commercial capitalists and landowners. Since then we have been governed from outside Parliament, first by our own employers, and of late by the financiers of all nations and races." (26)

Mosley believed the House of Commons tamed those who wished to change society: "Many a good revolutionary has arrived at Westminster roaring like a lion, only a few months later to be cooing as the tame dove of his opponent. The bar, the smoking room, the lobby, the dinner tables of his constituents' enemies, and the atmosphere of the best club in the country, very quickly rob a people's champion of his vitality and fighting power. Revolutionary movements lose their revolutionary ardour as a result long before they ever reach power, and the warrior of the platform becomes the lap-dog of the lobbies." (27)

Mosley suggested this problem could be dealt with by the introduction of the Corporate State. The government would preside over corporations formed from the employers, trade unions and consumer interests. Within the guidelines of a national plan, these corporations would work out its own policy for wages, prices, conditions of employment, investment and terms of competition. Government would intervene only to settle deadlocks between unions and employers. Strikes would be made illegal.

Mosley's critics on the left argued that his Corporate State would enshrine the freedom of capitalists to exploit a working-class deprived of both its industrial and political weapons. Mosley believed that working-class political parties and unions would not be needed: "In such a system (the Corporate State) there is no place for parties and for politicians. We shall ask the people for a mandate to bring an end the Party system and the Parties. We invite them to enter a new civilisation. Parties and the party game belong to the old civilisation, which has failed." (28)

The January Club

The January Club was a product of the dinners and functions held by Robert Forgan, a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) during the autumn of 1933. The chairman of the January Club was Sir John Collings Squire, who claimed that membership was open to anyone who was "in sympathy with the the Fascist movement". Squire's biographer, Patrick J. Howarth, claimed that "They believed that the present democratic system of government in this country must be changed, and although the change was unlikely to come about suddenly, as it had in Italy and Germany, they regarded it as inevitable." (29) The secretary of the January Club was Captain H. W. Luttman-Johnson and it has been argued that "the correspondence between Luttman-Johnson and Mosley leaves no doubt that the January Club was designed as a front organization for the BUF". (30)

The January Club stated that its objectives included: "(i) To bring together men who are interested in modern methods of government. (ii) To provide a platform for leaders of Fascist and Corporate State thought. The club, however, will not formulate any policy of its own. (iii) To enable those who are propagating Fascism to hear the views of those who, while sympathizing with and students of twentieth-century political thought, are not themselves Fascists." (31)

The journalist and novelist, Cecil Roberts, attended one of their first meetings with his friend, Francis Yeats-Brown. He later recalled: The majority appeared to be tentative enquirers like myself. Some of the speeches struck a note of accord in their deprecation of the lassitude of our Government. On invitation I spoke myself, expressing all my pent-up indignation and alarm. Sir John Squire, who was present, an enquirer like myself, repeatedly congratulated me on that speech." (32)

Members of the January Club included Basil Liddell Hart, General Sir Hubert Gough, Wing-Commander Sir Louis Greig, Gentleman Usher to the King George VI, Sir Henry Fairfax-Lucy, Sir Philip Magnus-Allcroft MP, Sir Thomas Moore and Ralph Blumenfeld, the editor of the Daily Express. (33) Speakers at the meetings included Mary Allen, the commander of the Women's Police Service since 1920, William Joyce, Muriel Innes Currey, Alexander Raven Thomson and Air Commodore John Adrian Chamier. (34) Richard C. Thurlow has pointed out that the January Club, was part of the "considerable hidden history of British fascism." (35)

The most important member of the January Club was the newspaper baron, Harold Harmsworth, the 1st Lord Rothermere. According to S. J. Taylor, the author of The Great Outsiders: Northcliffe, Rothermere and the Daily Mail (1996), as early as 1931, Rothermere was offering to place "the whole of the Harmsworth press at Mosley's disposal". Rothermere believed that Mosley and his fledgling Fascists represented "sound, commonplace, Conservative doctrine". Inspired by "loyalty to the throne and love of country", they were little more than an energetic wing of the Conservative Party". (36)

Stephen Dorril has explained that the men who established the January Club later admitted that its main objective was to provide a platform for Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists (BUF). (37) "At a conference in the Home Office in November 1933 attended by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, two officers of MI5 and a superintendent from Special Branch, it was decided that information should be systematically collected on fascism in the United Kingdom." (38) These reports from MI5 pointed out that the January Club was "a powerhouse for the development of Fascist culture" and "it brought fascism to the notice of large numbers of people who would have considered it much less favourably otherwise." (39)

After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party, were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill. (40)

Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party became banned organisations. Party activists still in the country were arrested. A month later Hitler announced that the Catholic Centre Party, the Nationalist Party and all other political parties other than the NSDAP were illegal, and by the end of 1933 over 150,000 political prisoners were in concentration camps. Hitler was aware that people have a great fear of the unknown, and if prisoners were released, they were warned that if they told anyone of their experiences they would be sent back to the camp. (41)

Lord Rothermere produced a series of articles acclaiming the new regime. The most famous of these was on the 10th July when he told readers that he "confidently expected" great things of the Nazi regime. He also criticized other newspapers for "its obsession with Nazi violence and racialism", and assured his readers that any such deeds would be "submerged by the immense benefits that the new regime is already bestowing on Germany." He pointed out that those criticizing Hitler were on the left of the political spectrum. (42)

Hitler acknowledged this help by writing to Rothermere: "I should like to express the appreciation of countless Germans, who regard me as their spokesman, for the wise and beneficial public support which you have given to a policy that we all hope will contribute to the enduring pacification of Europe. Just as we are fanatically determined to defend ourselves against attack, so do we reject the idea of taking the initiative in bringing about a war. I am convinced that no one who fought in the front trenches during the world war, no matter in what European country, desires another conflict." (43) In another article Lord Rothermere called for Hitler to be given back land in Africa that had been taken as a result of the Versailles Treaty. (44)

Success in Worthing

At an election meeting in Broadwater on 16th October 1933, Charles Bentinck Budd revealed he had recently met Sir Oswald Mosley and had been convinced by his political arguments and was now a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Budd added that if he was elected to the local council "you will probably see me walking about in a black shirt". (45)

Budd won the contest and the national press reported that Worthing was the first town in the country to elect a Fascist councillor. Worthing was now described as the "Munich of the South". A few days later Mosley announced that Budd was the BUF Administration Officer for Sussex. Budd also caused uproar by wearing his black shirt to council meetings. (46)

On Friday 1st December 1933, the BUF held its first public meeting in Worthing in the Old Town Hall. According to one source: "It was crowded to capacity, with the several rows of seats normally reserved for municipal dignitaries and magistrates now occupied by forbidding, youthful men arrived in black Fascist uniforms, in company with several equally young women dressed in black blouses and grey skirts." (47)

Budd reported that over 150 people in Worthing had joined the British Union of Fascists. Some of the new members were former communists but the greatest intake had come from increasingly disaffected Conservatives. The Weekly Fascist News described the growth in membership as "phenomenal" as a few months ago members could be counted on one's fingers, and now "hundreds of young men and women -.together with the many leading citizens of the town - now participated in its activities". (48)

The mayor of Worthing, Harry Duffield, the leader of the Conservative Party in the town, was most favourably impressed with the Blackshirts and congratulated them on the disciplined way they had marched through the streets of Worthing. He reported that employers in the town had written to him giving their support for the British Union of Fascists. They had "no objection to their employees wearing the black shirt even at work; and such public spirited action on their part was much appreciated." (49)

The Daily Mail and the British Union of Facists

Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, the press baron, was a great supporter of Adolf Hitler. According to James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979): "Shortly after the Nazis' sweeping victory in the election of September 14, 1930, Rothermere went to Munich to have a long talk with Hitler, and ten days after the election wrote an article discussing the significance of the National Socialists' triumph. The article drew attention throughout England and the Continent because it urged acceptance of the Nazis as a bulwark against Communism... Rothermere continued to say that if it were not for the Nazis, the Communists might have gained the majority in the Reichstag." (50)

Louis P. Lochner, argues in his book, Tycoons and Tyrant: German Industry from Hitler to Adenauer (1954) that Lord Rothermere provided funds to Hitler via Ernst Hanfstaengel. When Hitler became Chancellor on 30th January 1933, Rothermere produced a series of articles acclaiming the new regime. "I urge all British young men and women to study closely the progress of the Nazi regime in Germany. They must not be misled by the misrepresentations of its opponents. The most spiteful distracters of the Nazis are to be found in precisely the same sections of the British public and press as are most vehement in their praises of the Soviet regime in Russia." (51)

George Ward Price, the Daily Mail's foreign correspondent developed a very close relationship with Adolf Hitler. According to the German historian, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen: "The famous special correspondent of the London Daily Mail, Ward Price, was welcomed to interviews in the Reich Chancellery in a more privileged way than all other foreign journalists, particularly when foreign countries had once more been brusqued by a decision of German foreign policy. His paper supported Hitler more strongly and more constantly than any other newspaper outside Germany." (52)

Franklin Reid Gannon, the author of The British Press and Germany (1971), has claimed that Hitler regarded him as "the only foreign journalist who reported him without prejudice". (53) In his autobiography, Extra-Special Correspondent (1957), Ward Price defended himself against the charge he was a fascist by claiming: "I reported Hitler's statements accurately, leaving British newspaper readers to form their own opinions of their worth." (54)

Lord Rothermere also gave full support to Oswald Mosley and the National Union of Fascists. He wrote an article, Hurrah for the Blackshirts, on 22nd January, 1934, in which he praised Mosley for his "sound, commonsense, Conservative doctrine". Rothermere added: "Timid alarmists all this week have been whimpering that the rapid growth in numbers of the British Blackshirts is preparing the way for a system of rulership by means of steel whips and concentration camps. Very few of these panic-mongers have any personal knowledge of the countries that are already under Blackshirt government. The notion that a permanent reign of terror exists there has been evolved entirely from their own morbid imaginations, fed by sensational propaganda from opponents of the party now in power. As a purely British organization, the Blackshirts will respect those principles of tolerance which are traditional in British politics. They have no prejudice either of class or race. Their recruits are drawn from all social grades and every political party. Young men may join the British Union of Fascists by writing to the Headquarters, King's Road, Chelsea, London, S.W." (55)

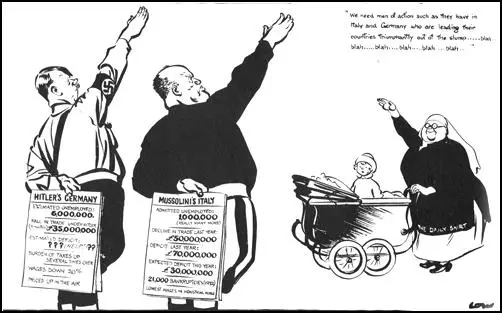

David Low, a cartoonist employed by the Evening Standard, made several attacks on Rothermere's links to the fascist movement. In January 1934, he drew a cartoon showing Rothermere as a nanny giving a Nazi salute and saying "we need men of action such as they have in Italy and Germany who are leading their countries triumphantly out of the slump... blah... blah... blah... blah." The child in the pram is saying "But what have they got in their other hands, nanny?" Hitler and Mussolini are hiding the true records of their periods in government. Hitler's card includes, "Hitler's Germany: Estimated Unemployed: 6,000,000. Fall in trade under Hitler (9 months) £35,000,000. Burden of taxes up several times over. Wages down 20%." (56)

Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Evening Standard, was a close friend and business partner of Lord Rothermere, and refused to allow the original cartoon to be published. At the time, Rothermere controlled forty-nine per cent of the shares. Low was told by one of Beaverbrook's men: "Dog doesn't eat dog. It isn't done." Low commented that it was said as "though he were giving me a moral adage instead of a thieves' wisecrack." He was forced to make the nanny unrecgnisable as Rothermere and had to change the name on her dress from the Daily Mail to the Daily Shirt. (57)

The Daily Mail continued to give its support to the fascists. Lord Rothermere allowed fellow member of the January Club, Sir Thomas Moore, the Conservative Party MP for Ayr Burghs, to publish pro-fascist articles in his newspaper. Moore described the BUF as being "largely derived from the Conservative Party". He added "surely there cannot be any fundamental difference of outlook between the Blackshirts and their parents, the Conservatives?" (58)

In April 1934, The Daily Mail published an article by Randolph Churchill that praised a speech that Mosley made in Leeds: "Sir Oswald's peroration was one of the most magnificent feats of oratory I have ever heard. The audience which had listened with close attention to his reasoned arguments were swept away in spontaneous reiterated bursts of applause." (59)

Violence and the British Union of Fascists

The London Evening News, another newspaper owned by Harold Harmsworth, 1st Lord Rothermere, found a more popular and subtle way of supporting the Blackshirts. It obtained 500 seats for a BUF rally at the Royal Albert Hall and offered them as prizes to readers who sent in the most convincing reasons why they liked the Blackshirts. Rothermere's , The Sunday Dispatch, even sponsored a Blackshirt beauty competition to find the most attractive BUF supporter. Not enough attractive women entered and the contest was declared void. (60)

David Low was one of those who attended the meeting at the Royal Albert Hall: "Mosley spoke effectively at great length. Delivery excellent, matter reckless. Interruptions began, but no dissenting voice got beyond half a dozen sentences before three or four bullies almost literally jumped on him, bashed him and lugged him out. Two such incidents happened near me. An honest looking blue-eyed student type rose and shouted indignantly 'Hitler means war!' whereupon he was given the complete treatment." (61)

Nicholas Mosley pointed out that his father was an outstanding communicator: "He had an amazing memory for figures. He liked to be challenged by hecklers, because he felt confident in his powers of repartee. But above all what held his audiences and almost physically lifted them were those mysterious rhythms and cadences which a mob orator uses and which, combined with primitively emotive words, play upon people's minds like music. This power that Oswald Mosley had with words did not always, in the long run, work to his advantage. There were times when his audience was being lifted but he himself was being lulled into thinking the reaction more substantial than it was. After the enthusiasm had worn off like the effects of a drug an audience was apt to find itself feeling rather empty. (In the same way his girlfriends, one of them (Georgia Sitwell) once said, would feel somewhat ashamed after having been seduced.)" (62)

Oswald Mosley decided to hold a large British Union of Fascists rally at Olympia on 7th June. Soon after the meeting was announced, The Daily Worker issued a statement declaring that the Communist Party of Great Britain intended to demonstrate against Mosley by organized heckling inside the meeting and by a mass demonstration outside the hall. (63)

The CPGB did what it could to disrupt the meeting. As Robert Benewick, the author of The Fascist Movement in Britain (1972) pointed out: "They (the CPGB) printed illegal tickets. Groups of hecklers were stationed at strategic points inside the meeting, and Press interviews with their members were organized outside. First-aid stations were set up in near-by houses, and there were the inevitable parades, banners, placards and slogans. It was unlikely that weapons were officially authorized but this would not have prevented anyone from carrying them." (64) In fact, Philip Toynbee later admitted that he and Esmond Romilly both took knuckle-dusters to the meeting. (65)

About 500 anti-fascists including Vera Brittain, Richard Sheppard and Aldous Huxley, managed to get inside the hall. When they began heckling Oswald Mosley they were attacked by 1,000 black-shirted stewards. Several of the protesters were badly beaten by the fascists. Margaret Storm Jameson pointed out in The Daily Telegraph: "A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality?" (66)

Collin Brooks, was a journalist who worked for Lord Rothermere at the The Sunday Dispatch. He also attended the the rally at Olympia. Brooks wrote in his diary: "He (Mosley) mounted to the high platform and gave the salute - a figure so high and so remote in that huge place that he looked like a doll from Marks and Spencer's penny bazaar. He then began - and alas the speakers hadn't properly tuned in and every word was mangled. Not that it mattered - for then began the Roman circus. The first interrupter raised his voice to shout some interjection.The mob of storm troopers hurled itself at him. He was battered and biffed and hashed and dragged out - while the tentative sympathisers all about him, many of whom were rolled down and trodden on, grew sick and began to think of escape. From that moment it was a shambles. Free fights all over the show. The Fascist technique is really the most brutal thing I have ever seen, which is saving something. There is no pause to hear what the interrupter is saying: there is no tap on the shoulder and a request to leave quietly: there is only the mass assault. Once a man's arms are pinioned his face is common property to all adjacent punchers." Brooks also commented that one of his "party had gone there very sympathetic to the fascists and very anti-Red". As they left the meeting he said "My God, if ifs to be a choice between the Reds and these toughs, I'm all for the Reds". (67)

Several members of the Conservative Party were in the audience. Geoffrey Lloyd pointed out that Mosley stopped speaking at once for the most trivial interruptions, although he had a battery of twenty-four loud-speakers. The interrupters were then attacked by ten to twenty stewards. Mosley's claim that he was defending the right of freedom was "pure humbug" and his tactics were calculated to provide an "apparent excuse" for violence. (68) William Anstruther-Gray, the MP for North Lanark, agreed with Lloyd: "Frankly if anybody had told me an hour before the meeting at Olympia that I should find myself on the side of the Communist interrupters, I would have called him a liar." (69)

However, George Ward Price, of The Daily Mail disagreed and put all the blame on the demonstrators: "If the Blackshirts movement had any need of justification, the Red Hooligans who savagely and systematically tried to wreck Sir Oswald Mosley's huge and magnificently successful meeting at Olympia last night would have supplied it. They got what they deserved. Olympia has been the scene of many assemblies and many great fights, but never had it offered the spectacle of so many fights mixed up with a meeting." (70)

In the debate that took place in the House of Commons on the BUF rally, several Tory MPs defended Mosley. Michael Beaumont by admitting that he was an "anti-democrat and an avowed admirer of Fascism in other countries" and from what he observed inside the meeting, no one there "got anything more than he deserved". (71) Tom Howard, the MP for Islington South, admired Mosley for his determination to maintain the right of free speech. He was also worried that the BUF were taking members from the Tories: "The tens of thousands of young men who had joined the Blackshirts... are the best element of the country". (72)

Clement Attlee, the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, claimed to have evidence to demonstrate that the Blackshirts used "plain-clothes inciters to disorder" at their meetings and that the Blackshirts used deliberate incitement as an excuse for force. (73) Walter Citrine, the General Secretary of the Trade Union Congress, demanded an end to "the drilling and arming of civilian sections of the community" and deplored the inactivity of the police and the courts in dealing with the British Union of Fascists." (74)

Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister, admitted that there were similarities between the Conservative Party and the British Union of Fascists but because of its "ultramontane Conservatism... it takes many of the tenets of our own party and pushes them to a conclusion which, if given effect to, would, I believe, be disastrous to our country." (75) The government rejected a proposal for a public inquiry into the violence at the Olympia meeting but the Home Secretary gave several hints on the possibility of legislation that would help prevent trouble at political meetings. (76)

In July, 1934 Lord Rothermere suddenly withdrew his support from Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. The historian, James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979), argues: "The rumor on Fleet Street was that the Daily Mail's Jewish advertisers had threatened to place their adds in a different paper if Rothermere continued the pro-fascist campaign." Pool points out that sometime after this, Rothermere met with Hitler at the Berghof and told how the "Jews cut off his complete revenue from advertising" and compelled him to "toe the line." Hitler later recalled Rothermere telling him that it was "quite impossible at short notice to take any effective counter-measures." (77)

Vernon Kell, of MI5, reported to the Home Office that the rally at Olympia appeared to have had a negative impact on the future of the British Union of Fascists: "It is becoming increasingly clear that at Olympia Mosley suffered a check which is likely to prove decisive. He suffered it, not at the hands of the Communists who staged the provocations and now claim the victory; but at the hands of Conservative MPs, the Conservative press and all those organs of public opinion which made him abandon the policy of using his Defence Force to overwhelm interrupters." (78)

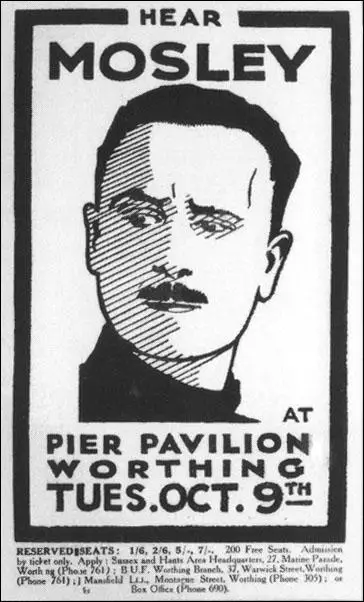

Oswald Mosley had developed a large following in Sussex after the election of Charles Bentinck Budd, the fascists only councillor. Budd arranged for Mosley and William Joyce to address a meeting at the Worthing Pavilion Theatre on 9th October, 1934. The British Union of Fascists covered the town with posters with the words "Mosley Speaks", but during the night someone had altered the posters to read "Gasbag Mosley Speaks Tripe". It was later discovered that this had been done by Roy Nicholls, the chairman of the Young Socialists. (79)

The venue was packed with fascist supporters from Sussex. According to Michael Payne: "Finally the curtain rose to reveal Sir Oswald himself standing alone on the stage. Clad entirely in black, the great silver belt buckle gleaming, the right arm raised in the Fascist salute, he was spell-bindingly illuminated in the hushed, almost reverential atmosphere by the glare of spotlights from right, left and centre. A forest of black-sleeved arms immediately shot up to hail him." (80)

The meeting was disrupted when a few hecklers were ejected by hefty East End bouncers. Mosley, however, continued his speech undaunted, telling his audience that Britain's enemies would have to be deported: "We were assaulted by the vilest mob you ever saw in the streets of London - little East End Jews, straight from Poland. Are you really going to blame us for throwing them out?" (81)

At the close of proceedings Mosley and Joyce, accompanied by a large body of blackshirts, marched along the Esplanade.They were protected by all nineteen available members of the Borough's police force. The crowd of protesters, estimated as around 2,000 people, attempted to block their path. A ninety-six-year-old woman, Doreen Hodgkins, was struck on the head by a Blackshirt before being escorted away. When the Blackshirts retreated inside, the crowd began to chant: "Poor old Mosley's got the wind up!" (82)

The Fascists went into Montague Street in an attempt to get to their headquarters in Anne Street. The author of Storm Tide: Worthing 1933-1939 (2008) has pointed out: "Sir Oswald, clearly out of countenance and feeling menaced, at once ordered his tough, battle-hardened bodyguards - all of imposing physique and, like their leader, towering over the policemen on duty - to close ranks and adopt their fighting stance which, unsurprisingly, as all were trained boxers, had been modelled on, and closely resembled, that of a prize fighter." (83)

Superintendent Clement Bristow later claimed that a crowd of about 400 people attempted to stop the Blackshirts from getting to their headquarters. Francis Skilton, a solicitor's clerk who had left his home at 30 Normandy Road to post a letter at the Central Post Office in Chapel Road, and got caught up in the fighting. A witness, John Birts, later told the police that Skilton had been "savagely attacked by at least three Blackshirts." (84)

According to The Evening Argus: "The fascists fought their way to Mitchell's Cafe and barricaded themselves inside as opponents smashed windows and threw tomatoes. As midnight loomed, they broke out and marched along South Street to Warwick Street. One woman bystander was punched in the face in what witnesses described as 'guerrilla warfare'. There were casualties on both sides as a 'seething, struggling mass of howling people' became engaged in running battles. People in nightclothes watched in amazement from bedroom windows overlooking the scene." (85)

The next day the police arrested Oswald Mosley, Charles Budd, William Joyce and Bernard Mullans and accused them of "with others unknown they did riotously assemble together against the peace". The court case took place on 14th November 1934. Charles Budd claimed that he telephoned the police three times on the day of the rally to warn them that he believed "trouble" had been planned for the event. A member of the Anti-Fascist New World Fellowship had told him that "we'll get you tonight". Budd had pleaded for police protection but only four men had turned up that night. He argued that there had been a conspiracy against the BUF that involved both the police and the Town Council.

Several witnesses gave evidence in favour of the BUF members. Eric Redwood - a barrister from Chiddingfield, said that the trouble was caused by a gang of "trouble-seeking roughs" and that Budd, Mosley, Joyce and Mullans "acted with admirable restraint". Herbert Tuffnell, a retired District Commissioner of Uganda, also claimed that it was the anti-fascists who started the fighting. (86)

Joyce, in evidence, said that "any suggestion that they came down to Worthing to beat up the crowd was ridiculous in the highest degree. They were menaced and insulted by people in the crowd." Mullans claimed that told an anti-fascist demonstrator that he "should be ashamed for using insulting language in the presence of women". The man then hit in the eye and he retaliated by punching the man in the mouth. (87)

John Flowers, the prosecuting council told the jury that "if you come to the conclusion that there was an organised opposition by roughs and communists and others against the Fascists... that this brought about the violence and that the defendants and their followers were protecting themselves against violence, it will not be my duty to ask you to find them guilty." The jury agreed and all the men were found not guilty. (88)

Oswald Mosley and Anti-Semitism

In the early days of the British Union of Fascist, Mosley concentrated on the need to introduce the corporate state. It was not until "October, 1934, anti-semitism was granted a starring role in the theory, strategy and day-to-day activity of Britain's fascist movement." According to David Rosenberg, the author of Battle for the East End: Jewish Responses to Fascism in the 1930s (2011), "Mosley invited a confrontation with the Jewish community, and challenged its leaders. He accused them of betraying the national interest, capturing and monopolising economic resources and driving Britain to a needless war with Germany." (89)

On one occasion, the Jewish boxer, Ted "Kid" Lewis (born Solomon Mendeloff), punched Mosley in the face after he admitted to being anti-Semitic. Harold Nicolson advised Mosley against following the policy of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany. He argued that an "openly anti-Semitic movement would be counter-productive, in terms of converting public opinion, because of Britain's underlying liberal culture." (90)

Mosley rejected this advice and began to make violent anti-Semitic speeches that received praise from Hitler. Mosley responded by sending Hitler a telegram: "Please receive my greatest thanks for your kind telegram in relation to my speech in Leicester, which was received while I was away from London. I esteem greatly your advice in the midst of our hard struggle. The forces of Jewish corruption must be overcome in all great countries before the future of Europe can be made secure in justice and peace. Our struggle to this end is hard, but our victory is certain." (91)

Mosley decided to develop a long-term electoral strategy of supporting anti-Semitic campaigns in Jewish areas. Of the 350,000 British Jews, about 230,000 lived in London, 150,000 of them in the East End. In October 1935, Mosley had ordered John Becket and A. K. Chesterton to promote anti-Semitism in those places with the highest number of Jews. (92) According to Robert Skidelsky, "Sixty thousand or so Jews were to be found in Stepney; another 20,000 or so in Bethnal Green; with smaller numbers in Hackney, Shoreditch and Bow." (93)

George Lansbury, the leader of the Labour Party and the M.P. for Bow & Bromley, complained about the activities of the BUF and stated that "unless this thing is put an end to - I have known East London all my life - there will one of these be such an outburst as few of us would care to contemplate." Denis Nowell Pritt, the Labour M.P. for Hammersmith North, feared that if the government did not act there would be "pogroms in this country." (94)

The BUF also became active in other cities with significant Jewish populations, including Manchester (35,000) and Leeds (30,000). This stimulated anti-fascist organisations. In September, 1936, a BUF march to Holbeck Moor, clashed with a hostile demonstration of 20,000 people in which Mosley and many other fascists were attacked and injured by missiles. (95)

In response to complaints from local Jewish residents, the Manchester police attended all fascist meetings and kept notes. However, they decided that BUF meetings were "conducted in a very orderly manner and without giving any cause for objection", and argued that trouble only arose if Jews attended and interrupted the speakers. At a meeting in Manchester in June 1936 Jock Houston referred to Jews as the international enemy, dominating banks and commerce and fomenting war between war between Britain and Germany. However, the Attorney General Donald Somervell, told complainants that no criminal offence had been committed." (96)

The Battle of Cable Street

In an attempt to increase support for their campaign against the Jews, the British Union of Fascists announced its attention of marching through the East End on 4th October 1936, wearing their Blackshirt uniforms. The Jewish People's Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism produced a petition that stated: "We the undersigned citizens of East London, view with grave concern the proposed march of the British Union of Fascists upon East London. The avowed object of the Fascist movement in Great Britain is the incitement of malice and hatred against sections of the population. It aims to further ends which seek to destroy the harmony and goodwill which has existed for centuries among the East London population, irrespective of differences in race and creed. We consider racial incitement, by a movement which employs flagrant distortions of the truth and degrading calumny and vilification, as a direct and deliberate provocation to attack. We therefore make an appeal to His Majesty's Secretary of State for Home Affairs to prohibit such matters and thus retain peaceable and amicable relations between all sections of East London's population." (97)

Within 48 hours over 100,000 people signed the petition and it was presented to 2nd October deputation was headed by Father St John Beverley Groser, James Hall, the Labour Party M.P. for Whitechapel, and Alfred M. Wall (Secretary of the London Trades Council). (98) George Lansbury, the M.P. for Bow & Bromley, also wrote to John Simon, the Home Secretary, and asked for the march to be diverted. (99) Simon refused and told a deputation of local mayors that he would not interfere as he did not wish to infringe freedom of speech. Instead he sent a large police escort in an attempt to prevent anti-fascist protesters from disrupting the march. (100)

The Independent Labour Party responded by issuing a leaflet calling on East London workers to take part in the counter demonstration which assembles at Aldgate at 2.p.m. (101) As a result the anti-fascists, adopting the slogan of the Spanish Republicans defending Madrid "They Shall Not Pass" and developed a plan to block Mosley's route. One of the key organizers was Phil Piratin, a leading figure in the Stepney Tenants Defence League. Denis Nowell Pritt and other members of the Labour Party also took part in the campaign against the march. (102)

The Jewish Chronicle told its readers not to take part in the demonstration: "Urgent Warning. It is understood that a large Blackshirt demonstration will be held in East London on Sunday afternoon. Jews are urgently warned to keep away from the route of the Blackshirt march from their meetings. Jews who, however innocently, became involved in any possible disorders will be actively helping anti-Semitism and Jew-baiting. Unless you want to help the Jew-baiters - Keep Away." (103)

The Daily Herald reported that by "1.30 p.m.... anti-Fascists had massed in tens of thousands. They formed a solid block at the junction of Commercial Street, Whitechapel Road and Aldgate. It was through this area that Mosley would have to reach his goal, Victoria Park, Stepney and the Socialists, Jews and Communists of the East End were determined that 'Mosley should not pass!' At the time every available policeman - about 10,000 in all - was converging on Whitechapel from all parts of London. Mounted police rode into the huge throng and forced the demonstrators back into the streets. Cordons were then flung across to keep a clear space for the marchers." (104)

Father St John Beverley Groser, of Christ Church, Watney Street, was a Christian Socialist and was one of the main organisers of the demonstration. He was hit several times by police batons and suffered a broken nose. The Church authorities were very unhappy with his involvement and his licence to preach was removed for a time. He had been previously forced to resign from the chuch after supporting the trade union movement during the General Strike. (105)

By 2.00 p.m. 50,000, people had gathered to prevent the entry of the march into the East End, and something between 100,000 and 300,000 additional protesters waited on the route. Barricades were erected across Cable Street and the police endeavoured to clear a route by making repeated baton charges. (106) One of the demonstrators said that he could see "Mosley - black-shirted himself - marching in front of about 3,000 Blackshirts and a sea of Union Jacks. It was as though he were the commander-in-chief of the army, with the Blackshirts in columns and a mass of police to protect them." (107)

Eventually at 3.40 p.m. Sir Philip Game, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in London, had to accept defeat and told Mosley that he had to abandon their march and the fascists were escorted out of the area. Max Levitas, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Stepney later pointed out: "It was the solidarity between the Labour Party, the Communist Party and the trade union movement that stopped Mosley's fascists, supported by the police, from marching through Cable Street." (108) William J. Fishman said: "I was moved to tears to see bearded Jews and Irish Catholic dockers standing up to stop Mosley. I shall never forget that as long as I live, how working-class people could get together to oppose the evil of fascism." (109)

The Manchester Guardian supported the Home Secretary's decision to allow the BUF's march as it demonstrated that the Fascists had the right to hold a procession, but correctly banned it, when it showed signs of getting out of control. (110) The Times condemned the actions of the anti-fascists and concluded, "that this sort of hooliganism must clearly be ended, even if it involves a special and sustained effort from the police authorities." (111) The Daily Telegraph praised the Police Commissioner Hugh Trenchard "as he was on the side of free speech, and those who assembled to resist the march threatened it." (112)

A total of 79 anti-fascists were arrested at during the Battle of Cable Street. Several of these men received a custodial sentence. This included the 21 year-old, Charlie Goodman. One of his prison experiences highlighted the conflict between the conservative Jewish establishment and left-wing Jews: "I was visited by a Mr Prince from the Jewish Discharged Prisoners Aid Society... an arm of the Board of Deputies who called all the Jewish prisoners together." He asked them what crimes they had committed. The first five or six prisoners admitted to crimes such as robbery and he replied, "Don't worry, we'll look after you." When he asked Goodman he replied, "fighting fascism". This provoked Prince into saying: "You are the kind of Jew who gives us a bad name... It is people like you that are causing all the aggravation to the Jewish people." (113)

According to one police report, Mick Clarke, one of the fascist leaders in London told one meeting: "It is about time the British people of the East End knew that London's pogrom is not very far away now. Mosley is coming every night of the week in future to rid East London and by God there is going to be a pogrom." As John Bew has pointed out: "That was not the end of the matter. Labour Party meetings were frequently stormed by fascists over the following months. Stench bombs would be put through a window, doors would be kicked open, and fists would fly." (114)

The Battle of Cable Street forced the government to reconsider its approach to the British Union of Fascists and passed the 1936 Public Order Act. This gave the Home Secretary the power to ban marches in the London area and police chief constables could apply to him for bans elsewhere. The 1936 Public Order Act also made it an offence to wear political uniforms and to use threatening and abusive words. Herbert Morrison of the Labour Party claimed this act "smashed the private army and I believe commenced the undermining of Fascism in this country." (115)

During this period Oswald Mosley was having an affair with Diana Mitford, the daughter of the 2nd Baron Redesdale, one of Mosley's wealthy supporters. Diana and her sister, Unity Mitford, were regular visitors to Nazi Germany. While there they met Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, Herman Goering, and other leaders of the Nazi Party. Hitler told newspapers in Germany that Unity was "a perfect specimen of Aryan womanhood". In October 1936, Diana and Mosley were secretly married in the house of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. Hitler was one of only six guests at the ceremony. (116)

Oswald Mosley now decided to use democratic methods to take control of the East End of London. In February, 1937, Mosley announced that the British Union of Fascists would be taking part in London's municipal elections the following month. During the campaign BUF candidates attacked Jewish financiers, landlords, shopkeepers and politicians. Mosley also attacked the Labour Party for not solving London's housing problem. The main slogan of the BUF was "Vote British and Save London".

The election results announced on 6th March 1937 revealed that the BUF won only 18% of the votes cast in the seats they were contesting. Mick Clarke and Alexander Raven Thompson did best of all with winning 23% of the vote in Bethnal Green. This was less than half of those of the Labour candidates. The BUF vote mainly came from disillusioned supporters of the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party rather than that of Labour. This suggested "that Mosley had as yet made little political headway among the ordinary working-class of East London - dockers, transport men, shipyard workers." (117)

Despite this set-back, the British Union of Fascists continued their campaign against the Jews who they insisted in calling "aliens". As the Jewish historian, David Rosenberg, has pointed out, "the presence of a well-organized Fascist Party with extensive propaganda resources at its disposal ensured that the treatment of aliens remained an issue in political debate that other parties, including the government, could not ignore. The Fascists were helped by the way newspapers reported on immigration during this period. Aliens allegedly threatened the jobs and homes of Englishmen, undermined the country's security, brought with them diseases (or ill-considered methods of treatment) and crime. German, Austrian and Czech Jewish immigrants were the object of an anti-alien rhetoric that harked back to the turn of the century." (118)

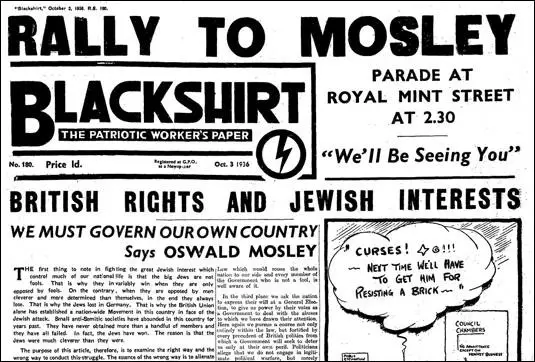

The BUF attempted to explain the defeat in its newspaper, The Blackshirt: "Mosley chose deliberately to commence his attack in the strongholds of the Jewish race. The Jew is a wily politician and replied by plumping solidly for Labour candidates whom he considered in those constituencies to be most likely to defeat the Blackshirt... It would seem that "the Englishman does not take readily to new movements." (119)

The Daily Mail led this campaign against Jews fleeing from Europe being allowed into the country and in August 1938 published the headline "Aliens Pouring into Britain". The Sunday Express also played a prominant role in this attempt to increase the hostility to immigrants. In one article it claimed: "In Britain half a million Jews find their home. They are never persecuted and, indeed, in many respects the Jews are given favoured treatment here. But just now there is a big influx of foreign Jews in Britain. They are overrunning the country. They are trying to enter the medical profession in great numbers. Worst of all, many of them are holding themselves out to the public as psychoanalysts." (120)

In April 1939, Charles E. Hudson and Jorian Jenks, two members of the British Union of Fascists in Sussex, answered questions on policy at a meeting in Bognor Regis. The two men were both questioned about the Fascist attitude to the Jews, and Jenks argued "the Jews were aliens to this country, and as guests, were expected to achieve the standard of behaviour set up in this country". If they failed to do this and the BUF were in control "they would be deported". (121)

Primary Sources

(1) David Low, Autobiography (1956)

Mosley was young, energetic, capable and an excellent speaker. Since I had met him in 1925 he had graduated from close friendship with MacDonald to a job in the second Labour Government; but he had become disgusted with the evasions over unemployment and had resigned to start a party of his own.

Unfortunately at the succeeding general election he fell ill with influenza and his party-in-embryo, deprived of his brilliant talents, was wiped out. Mosley was too ambitious to retire into obscurity. Looking around for a 'vehicle' he united himself to the British Fascists, rechristened 'the Blackshirts', and acquired almost automatically the encouragement of Britain's then biggest newspaper, the Daily Mail, which was more than willing to extend its admiration for the Italian original to the local imitation. That was a fateful influenza germ.

(2) Lord Rothermere, The Daily Mirror (22nd January, 1934)

Timid alarmists all this week have been whimpering that the rapid growth in numbers of the British Blackshirts is preparing the way for a system of rulership by means of steel whips and concentration camps.

Very few of these panic-mongers have any personal knowledge of the countries that are already under Blackshirt government. The notion that a permanent reign of terror exists there has been evolved entirely from their own morbid imaginations, fed by sensational propaganda from opponents of the party now in power.

As a purely British organization, the Blackshirts will respect those principles of tolerance which are traditional in British politics. They have no prejudice either of class or race. Their recruits are drawn from all social grades and every political party.

Young men may join the British Union of Fascists by writing to the Headquarters, King's Road, Chelsea, London, S.W.

(3) David Low attended one of the public meetings held by the British Union of Fascists in 1936.

Mosley spoke effectively at great length. Delivery excellent, matter reckless. Interruptions began, but no dissenting voice got beyond half a dozen sentences before three or four bullies almost literally jumped on him, bashed him and lugged him out. Two such incidents happened near me. An honest looking blue-eyed student type rose and shouted indignantly "Hitler means war!" whereupon he was given the complete treatment.

(4) George Ward Price described how the Black Shirts dealt with anti-fascist demonstrators in The Daily Mail (8th June 1934)

If the Blackshirts movement had any need of justification, the Red Hooligans who savagely and systematically tried to wreck Sir Oswald Mosley's huge and magnificently successful meeting at Olympia last night would have supplied it.

They got what they deserved. Olympia has been the scene of many assemblies and many great fights, but never had it offered the spectacle of so many fights mixed up with a meeting.

(5) Collin Brooks, diary entry (6th June, 1934)

The advertised time of the great oration was eight o'clock. At 8.45 the searchlights were directed to the far end, the Blackshirts lined the centre corridor - and trumpets braved as a great mass of Union Jacks surmounted by Roman plates passed towards the platform. Everybody thought this was Mosley and stood and cheered and saluted. Only it wasn't Mosley. He came some few minutes later at the head of his chiefs of craft. In consequence the second greeting was an anti-climax. He mounted to the high platform and gave the salute - a figure so high and so remote in that huge place that he looked like a doll from Marks and Spencer's penny bazaar. He then began - and alas the speakers hadn't properly tuned in and every word was mangled. Not that it mattered - for then began the Roman circus. The first interrupter raised his voice to shout some interjection.The mob of storm troopers hurled itself at him. He was battered and biffed and hashed and dragged out - while the tentative sympathisers all about him, many of whom were rolled down and trodden on, grew sick and began to think of escape. From that moment it was a shambles. Free fights all over the show. The Fascist technique is really the most brutal thing I have ever seen, which is saving something. There is no pause to hear what the interrupter is saying: there is no tap on the shoulder and a request to leave quietly: there is only the mass assault. Once a man's arms are pinioned his face is common property to all adjacent punchers...

The breaking of glass off-stage added to the trepidation of old ladies and parsons in the audience who had come to support the 'patriots'. More free fights - more bashing and lashing and kickings - and a steady withdrawal of the ordinary audience. We left With Mosley still speaking and the loud speakers still preventing our hearing a word he said, and by that time the place was half empty. Outside, of course, were the one thousand police expecting more trouble, but I didn't wait to see the aftermath. One of our party had gone there very sympathetic to the fascists and very anti-Red. As we parted he said "My God, if ifs to be a choice between the Reds and these toughs, I'm all for the Reds".

(6) Margaret Storm Jameson, The Daily Telegraph (9th July, 1934)

A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue.... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality?

(7) Oswald Mosley, Message for British Union Members and Supporters (2nd September, 1939)

We have said a hundred times that if the life of Britain were threatened we would fight again, but I am not offering to fight in the quarrel of Jewish finance in a war from which Britain could withdraw at any moment she likes, with her Empire intact and her people safe. I am now concerned with only two simple facts. This war is no quarrel of the British people, this war is a quarrel of Jewish finance, so to our people I give myself for the winning of peace.

(8) Jessica Mitford, Hons and Rebels (1960)

On May Day the entire community turned out, men, women and children, home-made banners proclaiming slogans of the "United Front against Fascism" waving alongside the official ones. The long march to Hyde Park started early in the morning, contingents of the Labour Party, the Co-ops, the Communist Party, the Independent Labour Party marching through the long day to join other thousands from all parts of London in the traditional May Day labour festival.

Everyone took lunch in a paper bag, and there was much good-natured jostling and shouting of orders, and last-minute rounding up of children who had darted away in the crowd.

We had been warned that the Blackshirts might try to disrupt the parade, and sure enough there were groups of them lying in wait at several points along the way. Armed with rubber truncheons and knuckle-dusters, they leaped out from behind buildings; there were several brief battles in which the Blackshirts were overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of the Bermondsey men. Once I caught sight of two familiar, tall blonde figures: Boud (Unity Mitford) and Diana (Mitford), waving Swastika flags. I shook my fist at them in the Red Front salute, and was barely dissuaded by Esmond (Romilly) and Philip (Toynbee), who reminded me of my now pregnant condition, from joining the fray.

(9) David Cesarani, The Internment of Aliens in the 20th Century (1993)

As well as transmitting anti-alienism through the 1930s, the presence of a well-organized Fascist Party with extensive propaganda resources at its disposal ensured that the treatment of aliens remained an issue in political debate that other parties, including the government, could not ignore. Although the real strength of the fascists may have been slight, their spectre loomed large and provided a crucial justification for maintaining barriers against foreigners seeking to enter the country.

The main features of anti-alienism in the 1930s were no different from previous waves. Indeed, the continuity is at times astounding. Aliens allegedly threatened the jobs and homes of Englishmen, undermined the country's security, brought with them diseases (or ill-considered methods of treatment) and crime. German, Austrian and Czech Jewish immigrants were the object of an anti-alien rhetoric that harked back to the turn of the century. In June, 1938, for example, the Sunday Express pronounced that "just now there is a big influx of foreign Jews into Britain. They are overrunning the country". A characteristic headline in the Daily Mail in August 1938 ran "Aliens Pouring into Britain".

(10) Francis Beckett, writing about his father, John Beckett, in History Today (May 1994)

There is no evidence that Beckett was anti-Semitic before joining Mosley, but he does seem to have been psychologically ready to endorse the anti-Semitism he found in the BUF. And yet all this time he guarded a secret - guarded it so well that I only discovered it years after his death, and it has never been published before. He was, strictly speaking, a Jew, because his mother was a Jew.

He denied it when there was a rumour in BUF circles. It is a surprising and rather shocking lie from a man who was, most of the time, more truthful than was good for him.

He was the most unlikely fascist you could imagine. He was irreverent, spontaneous, funny. He loathed accepting orders. He spoke and wrote with fluency, humour, logic - the weapons of a democratic politician, not a demagogue. He had no time for the trappings of fascism, which he called "heel-clicking and petty militarism". He did not have the proper reverence and admiration for The Leader. He referred to Mosley as 'the Bleeder'. Mosley, who was a textbook fascist leader resented this: Beckett was not a textbook fascist lieutenant. He was shocked by some of the people who were attracted to fascism because it enabled them to strut about self-importantly in a uniform. He does not seem to have realised that all this was an intrinsic part of the creed he had embraced.

(11) William Joyce, Germany Calling (13th June, 1941)

National Socialism condemns wealth without responsibility, privilege without merit and it works to unite all classes in the common task... Communism (for the benefit of the few) preaches the law of the jungle. Communism is based on the lowest tendencies of rapacity ... In England I have seen crowds of sub-anthropoid creatures using razor blades and pieces of lead piping against disabled ex-Servicemen who happened to belong to patriotic movements or to the Conservative Party. In almost every case, they were led from behind by Jews. It is with creatures of the same kind that Churchill has made his pact. Small wonder that the truth is not to be expected from him. Small wonder that the darkness deepens over England as Europe sees the dawn of a New Order.

(11) Railton Freeman, a member of the British Union of Fascist, worked with William Joyce and Norman Baillie-Stewart on Germany Calling. His views on fascism was quoted by Adrian Weale in his book Renegades: Hitler's Englishmen (1994)

I have been bitterly opposed to the appalling menace of Soviet Communism for a long time. I have studied Moscow propaganda . . . and its hideous exploitation by World Jewry and I am more than dismayed by the fearful fate that awaits this country and western Europe, and eventually the whole world, when this menace overpowers them. I came to these conclusions long before I ever heard of Mosley or Hitler, therefore it is inaccurate to describe my views or actions as Nazi... National Socialism merely provided the one apparently solid barrier in the path of this Asiatic doctrine from which opposition could be made.

(12) Reverand James Louis Crosland, letter to Adolf Hitler (April, 1936)

In order that you may be able to fully understand the attitude of the British people towards the proposals put forward by the German Government, we the undersigned take this opportunity as representative of public opinion, to write and express our full approval of the proposals, and also our deep sympathy and understanding for the German people in their sincere effort to bring a lasting peace to the disturbed and troubled continent of Europe.

We feel that the proposals contain in themselves the essence of a plan which could bring a new order of civilization undreamt of in the annals of history and which would once and for all establish the peace of Europe on a solid and lasting foundation.

We sympathise with the German nation in their struggle for equal status with the other great nations of Europe, and we realise that a country with so high a culture, which has contributed so much in the field of music, science, and art, should find a worthy and honoured place in the community of nations. We realise the work that your Excellency has done for Germany in particular, and for Europe as a whole is driving the menace of Communism from our midst, and we desire above all a friendship with Germany and the German people. We firmly reject the proposed Staff talks as monstrous, they are entirely out of sympathy with the feelings of the British nation, and we accord our warmest approval action of the German Government in their re-militarisation of the Rhine zone as a counter measure to the Franco-Soviet Pact.

We sincerely trust that this letter may reach your Excellency safely and that it will give you an idea of the opinion of the British people.