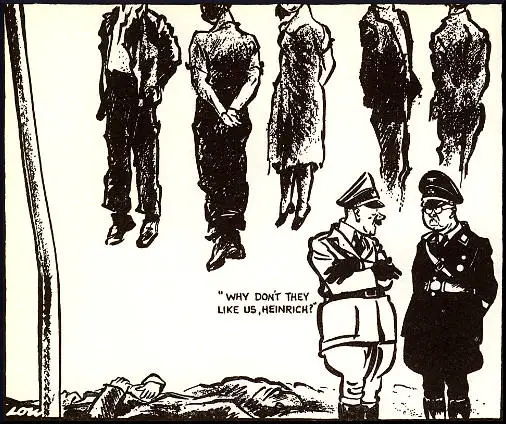

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Himmler, the second of three sons of Gerbhard Himmler, a Catholic schoolmaster, was born near Munich, Germany, on 7th October, 1900. When he was just two years old he suffered a serious lung infection and his mother took him to a mountain village where the air was pure. He was frequently ill and it has been claimed that as a result he was "overindulged". (1)

According to his first biographer, Willi Frischauer, the author of Himmler: The Evil Genius of the Third Reich (1953), in the evenings after dinner in the Himmler home, Professor Himmler would read to the boys from books on German history. By the time he entered secondary school he could recite the names and dates of all the famous battles and rivalled his teachers in knowledge of Germany's military past. (2)

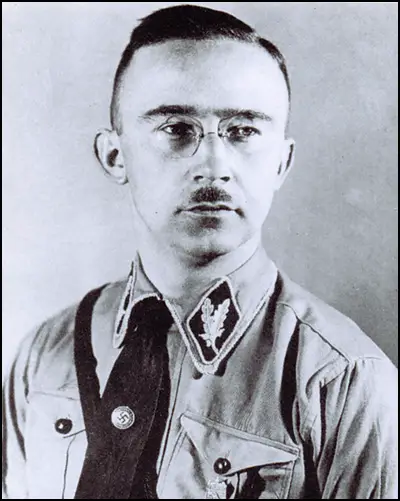

George Wolfgang Hallgarten recalls that while at school Himmler "was of scarcely average size, but downright podgy, with an uncommonly milk-white complexion, fairly short hair, and already wearing gold-rimmed glasses on his rather sharp nose; not infreqently he showed a half-embarrassed, half-sardonic smile either to excuse his short-sightedness or to stress a certain superiority." Hallgarten went on to say that he was hopeless at sport and his gym instructor, Carl Haggenmuller, was a source of terror to him. (3)

Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) has argued: "German society was agressively masculine. The tone was set by the Prussian military which had unified and now ruled the empire. The ideal was the warrior-hero of spartan simplicity... In such a society more than most, Himmler must have despised himself for his short sight, awkward, unathletic body, constitutional weakness and physical ineptitude, perhaps even have despised his father for being a civilian or one or other of his parents for handing him down his hateful qualities; and the periods of torture at Haggenmuller's hands must have driven these feelings of inferiority deep." (4)

First World War

In 1913 Gerbhard Himmler became deputy head of Landshut High School. Heinrich attended his father's school and it was not long before he was being bullied by the other students. For a boy brought up by his father on tales of historic battles, he was fascinated by the outbreak of the First World War. He wrote in his diary on 23rd August, 1914: "Victory of the German Crown Prince north of Metz.... Bavarian troops were very brave in the rough battle.... the whole city is bedecked with flags. The French and Belgians scarcely thought they would be chopped up so fast." (5)

The following month he was writing: "Now it's going along famously. I'm pleased about these victories, the more so because the French and especially the English are angry about them and the anger is not exactly insignificant. Falk (his friend at school) and I would like best of all to be fighting it out with them. Just look how the Germans... are not afraid even before a world of enemies... An English cavalry brigade has been thrashed (I'm glad! Hurrah!)" (6)

In 1916 Himmler joined the Jugendwehr (Youth Defence) which provided instruction in military subjects. He also started a daily regime of dumbbell exercises to strengthen his muscles. He also started a collection of newspaper cuttings about the war. Himmler was desperate to become involved in the war effort and on 6th October, the day before his seventeenth birthday, he left school to work at the War Welfare Office. Two months later he joined the 11th Bavarian Infantry Regiment. "Proud and delighted, he wrote to tell his friends and relations that he was now a soldier." (7)

The German Revolution

Himmler's hopes of being a German officer on the Western Front ended with the defeat of the country in November 1918. He found it particularly upsetting as his brother, Gebhard Himmler, had won the Iron Cross (First Class). Himmler returned to Regensburg where he joined the recently formed Bayerische Volkspartei (BVP), a right-wing nationalist organization setup to rally the conservative forces of the middle class and the rural workers against the communists and socialists. Himmler wrote to his father and advised him to join the BVP as it was the "only hope" for the country. "Now only for you. I don't know how it is in Landshut. Don't let mother go out alone at night. Not without protection. Be careful in your letters. You can't be sure." (8)

On 7th April, 1919, Max Levien declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. A few days later, Eugen Levine, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), arrived in Munich from Berlin. The leadership of the KPD was determined to avoid any repetition of the events in the capital when January, when its leaders, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, were murdered by the authorities. Levine was instructed that "any occasion for military action by government troops must be strictly avoided". Levine immediately set about reorganising the party to separate it off clearly from the anarcho-communists led by Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer. He reported back to Berlin that he had about 3,000 members of the KPD under his control." (9)

On hearing the news, Heinrich Himmler returned home and joined the Freikorps Landshut and became aide to the commanding officer. However, before he could see action, Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. On 1st May, 1919, the Freikorps entered the city and over the next two days Oven's troops easily defeated the Red Guards. Once again Himmler was denied the active service he craved. (10)

The Nazi Party

In 1919 he began studying agriculture at Munich Technical College. The following year he spent time working on a farm at Fridolfing. During this time he took a vow of chastity. In a diary entry he contrasted two types of people, "the melancholic, stern, among which I include myself", and the easy-going, hot-blooded sort who followed their desires without too much thought or sense of responsibility." (11)

Himmler did find himself attracted to one woman, named Inge Barco. He was horrified when he discovered she was Jewish. Like many people in Germany at the time, he held strong anti-Semitic views: "She is a quiet girl, not vain or toffee-nosed, places some value on good manners. No one would know she was a dancer. She is Viennese, but a Jewess, has however absolutely nothing of the Jew in her manner, at least so far as one can judge. At first I made several remarks about Jews, I ruled her out as one... She is no longer innocent as she freely admits. But she has given her body only from love." (12)

In July 1923 Himmler joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). He played a minor role at the Beer Hall Putsch in November 1923 when he carried the Reich War Flag at the Munich War Ministry. The rebellion was easily crushed and the leaders of the party, Adolf Hitler, Ernst Röhm, Rudolf Hess, Julius Steicher, Wilhelm Frick, Wilhelm Brückner, Hermann Kriebel, Walter Hewell, Friedrich Weber and Ernst Pohner were arrested and imprisoned. (13)

With the other leaders in prison, Gregor Strasser became the most significant figure in the Nazi Party. He joined forces with his brother, Otto Strasser, to establish the Berliner Arbeiter Zeitung, a left-wing newspaper, that advocated world revolution. It also supported Lenin and the Bolshevik government in the Soviet Union. Later that year, Strasser was elected to the Bavarian Legislature. Louis L. Snyder, has argued: "In this capacity he proved to be an able organizer, an indefatigable if weak speaker, a shrewd politician, and a lover of action.... Using his parliamentary immunity to protect him from libel suits and holding a free railway pass, he turned his energy to seeking the highest post in the National Socialist Party. He would push Hitler aside and replace him. Strasser regarded himself as a proud intellectual who had far more to offer the party than the emotional and unstable Hitler." (14)

In July, 1924, Himmler became Strasser's secretary. Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) has pointed out: "Strasser could not have made a better choice. Himmler not only shared his own passionate convictions, enjoying immersing himself in paperwork and bringing order to files, as he had at the student organisation, but he had learned to type after a fashion on a machine the family used at home, and he had his motorbike which enabled him to visit the remoter branches of the district." (15)

Otto Strasser later described his first impressions of Himmler: "A remarkable fellow. Comes from a strong Catholic family, but does not want to know anything from the Church. Looks like a half-starved shrew. But keen I tell you, incredibly keen. He has a motorbike. He is under way the whole day - from one farm to another - from one village to the next. Since I've had him our weapons have really been put into shape. I tell you, he's a perfect arms-NCO. He visits all the secret depots." (16)

Himmler served as secretary to Gregor Strasser and was a member of the socialist wing of the party. During this period he met Ernst Hanfstaengel who later wrote about him in his book, Hitler: The Missing Years (1957): "He had a pale, round, expressionless face, almost Mongolian, and a completely inoffensive air. Nor in his early years did I ever hear him advocate the race theories of what he was to become the most notorious executive. He studied to become a veterinary surgeon, although I doubt if he had ever become fully qualified. It was probably only part of the course he had taken as an agricultural administrator, but, for all I know, treating defenceless animals may have tended to develop that indifference to suffering which was to become his most frightening characteristic." (17)

Gauleiter Heinrich Himmler

In 1925 he became Gauleiter (district leader) in Lower Bavaria and in 1926 in Upper Bavaria. He also served as propaganda leader of the Nazi Party. In 1926 he met Margarete Boden in a hotel lobby at a Bavarian resort, Bad Reichenhall. He immediately saw her as his ideal woman. His brother, Gebhard Himmler, claimed he was particularly attracted to her blonde hair and her blue eyes. According to Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991): "Undoubtedly she impressed him as truly Aryan, although there was a width to her face and frame more suited to Wagnerian opera than to the ideal of Nordic womanhood." (18)

(If you are enjoying this article, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter and Google+ or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

It has been claimed by Hugh Thomas that Himmler had great difficulty in finding girlfriends: "The simple truth was that despite the moral bluster of the diaries, he lacked confidence. His timidity was probably largely based on his awareness of his looks. However, any potential sense of inadequacy was translated into contempt for those who did not share his limitations... Rather than consider his want of sexual success as undermining his masculinity, he grandly assumed the role of heroic defender of both men's and women's purity." At the age of twenty-one he had written in his diary: "I have experienced what it is like... to get all fired up... The girls are so far gone they no longer know what they are doing. It is the hot unconscious longing for the whole individual, for the satisfaction of a really powerful natural urge. For this reason it is also dangerous for the man, and involves so much responsibility. Depraved as they are of their will power, one could do anything with these girls and, at the same time one has to struggle with oneself." (19)

Otto Strasser claims that Marga, aged thirty-four, and therefore eight years older than Himmler, seduced him. Himmler told Strasser that she was the first woman with whom he had sexual relations. They married in July 1928. Margarete sold her share of the clinic and used the proceeds to buy a plot of land in Waldtrudering, near Munich, where they put up a prefabricated house.

Peter Padfield has pointed out: "Margarete ran a clinic she had opened with her father's money in Berlin. Apparently she distrusted conventional medicine; she was more interested in homeopathy, hypnosis, the old herbal remedies of the country. Despite having set herself up in Berlin, a sink of decadence according to his ideas, she apparently shared all his views of the good life of the land, so much so that she was prepared to sell her clinic and buy a smallholding to work with him." (20) A daughter, Gudrun Himmler, was born on 8th August, 1929. She was named after a character in a novel written by Himmler's favourite writer, Werner Jansen.

Himmler and Schutzstaffel (SS)

Heinrich Himmler was a devout follower of Adolf Hitler and believed that he was the Messiah that was destined to lead Germany to greatness. Hitler, who was always vulnerable to flattery, decided in January, 1929, that Himmler should become the new leader of his personal bodyguard, the Schutzstaffel (SS). At that time it consisted of 300 men. Himmler personally vetted all applicants to make sure that all were good "Aryan" types. Himmler later remembered that: "In those days we assembled the most magnificent Aryan manhood in the SS-Verfugungstruppe. We even turned down a man if he had one tooth filled." By the time the Nazi Party gained power in 1933 Himmler's SS had grown to a strength of 52,000.

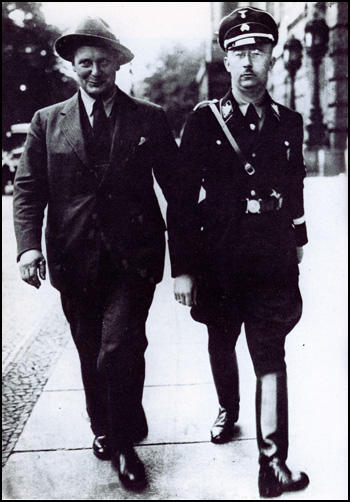

Karl Wolff met Himmler for the first time at the Reich Leadership School in Munich. "My first impression of Himmler was a great disappointment. I was considerably taller than him and had already been awarded the Iron Cross first and second class, and I had been an officer in one of the best and oldest regiments of the German Army - the Hessian Lifeguard Infantry Regiment in Darmstadt. On the other hand Himmler had no war decorations and had nothing in common with the front soldier; his whole bearing was rather sly and unmilitary, but he was very well read and tried to engage our interest with his acquired knowledge, and to enthuse us with the tasks of the SS." On 15th June 1933, Himmler appointed Wolff as his Chief of Staff. It has been claimed that the reason for this was that Himmler wanted to please senior officers in the German Army. Others have suggested that it was his links with bankers and industrialists that was important. (21)

Walter Dornberger also met him during this period. "He (Heinrich Himmler) looked to me like an intelligent elementary schoolteacher, certainly not a man of violence ... Under a brow of average height, two grey-blue eyes looked at me, behind glittering pince-nez, with an air of peaceful interrogation. The trimmed moustache below the straight, well-shaped nose traced a dark line on his unhealthy, pale features. The lips were colourless and very thin. Only the conspicuous receding chin surprised me. The skin of his neck was flaccid and wrinkled. With a broadening of his constant set smile, faintly mocking and sometimes contemptuous about the corners of the mouth, two rows of excellent white teeth appeared between the thin lips. His slender, pale, almost girlishly soft hands, covered with veins, lay motionless on the table throughout our conversation.... Himmler possessed the rare gift of attentive listening. Sitting back with legs crossed, he wore throughout the same amiable expression. His questions showed that he unerringly grasped what the technicians told him out of the wealth of their knowledge. The talk turned to war and the important questions in all our minds. He answered calmly and candidly. It was only at rare moments that, sitting with his elbows resting on the arms of the chair, he emphasised his words by tapping the tips of his fingers together. He was a man of quiet unemotional gestures. A man without words. (22)

Hugh Thomas has argued: "The pattern of a lifetime was established. He was a man of no outstanding intellectual gifts other than his memory, and no physical attraction, who set out to dominate the lives and minds of others. He was goaded by an unpleasant combination of ambition and officiousness that he disguised as high moral purpose. That he succeeded so well, then in a modest way, but later on a scale which brought disaster to mankind, must be attributed partly to hereditary make-up, and partly to the indoctrination of his father, which left him with exaggerated ideas of his own importance." (23)

Reinhard Heydrich & Himmler

Edouard Calic, the author of Himmler and the SS Empire (2009), points out that Reinhard Heydrich joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) in Hamburg on 31st May, 1931.(24) With the help of his girlfriend's family friend, Karl von Eberstein, Heydrich was able to obtain a meeting with Himmler. It has been claimed that he was impressed by Heydrich's "Nordic" appearance.

The Nazi Party decided to have its own intelligence and security body and so Himmler was asked to create the SD (Sicherheitsdienst). On 1st August, 1931, Heydrich became the head of the organization and it was kept distinct from the uniformed SS (Schutzstaffel). It has been claimed that Heydrich got the job because of his experience in Naval intelligence. However, Mark M. Boatner III has argued that Himmler had made his decision "not realizing he had been in signals, not naval intelligence." (25) Heydrich's fast task was to carry out an investigation of the SS: "The Security Service itself had its origins in reports early in 1931 that the Nazi Party had been infiltrated by its enemies. Himmler established the Security Service to investigate the claims." (26)

At first Heydrich had few resources to carry out his work. According to Andrew Mollo, the author of To The Death's Head: The Story of the SS (1982): "On a kitchen table, with a borrowed typewriter, a pot of glue, scissors and some files, Heydrich, now leader of the Security Service (Leiter des Sicherheitsdienstes), aided by his landlady and some out-of-work SS men, began to gather information on what the Nazis referred to as the 'radical opposition'. Top of the list were the political churches, Freemasons, Jews and Marxists. A titillating side-line was homosexuality and 'mattress affairs' both inside and out of the Nazi Party. Heydrich then toured the SS regional commands throughout Germany, and on his return began to recruit men of his own age and background into the SD. In contrast to the typical Nazi 'Lumpenpack' Heydrich sought bright young university graduates whose career prospects had been dimmed by depression. It was these young intellectuals from good families who were to give the SD its peculiar character. (27)

On 26th December, 1931, Reinhard Heydrich married Lina von Osten. In July 1932 he was promoted to Standartenführer-SS (full colonel) and became Himmler's valued chief of staff, and in this role helped develop the entire SS. During this period he developed good relationships with other powerful figures in the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) including Rudolf Hess and Martin Bormann.

Several writers have tried to explain the relationship between Heydrich and Himmler. Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) has argued: "To judge from letters and reports which they exchanged, the partnership was one of mutual trust and on Himmler's part affection... Himmler treated his protégé with special consideration and fondness... Both men were too complicated to conform to such simple analysis. Both were driven characters with deep-seated childhood complexes of inadequacy and they operated within a shifting minefield of power rivalries; neither was what he seemed... Himmler and Heydrich were a partnership and after more than a decade of success that virtually moulded the Nazi revolution they knew each other's strengths and weaknesses and each his position vis-a-vis the other as intimately as the partners in a marriage; as in a marriage no doubt the relationship changed and shifted subtly from time to time." (28)

Michael Burleigh, the author of The Third Reich: A New History (2001) claimed that the SS was "Himmler's mind projected on an institutional canvas, while the operational style largely derived from Heydrich.... Himmler's more outre obsessions should not distract from his manifestly astute grasp of how this highly chaotic and protean political system worked. Routinely out-manoeuvring his foes, his empire spread between the interstices of state, Party and army, throughout Germany, and then across the whole of occupied Europe. His manner may have been distracted and unassuming, but the coldness, moralising, prying and suspicion kept him in absolute control of subordinates, whose own utter ruthlessness was accompanied by human frailties which Himmler lacked." (29)

Richard Evans argues that Heydrich "became perhaps more universally and cordially feared and disliked than any other leading figure in the Nazi regime" and had the qualities that Himmler needed: "Unsentimental, cold, efficient, power-hungry and utterly convinced that the end justified the means, he soon won Himmler over to his ambitious vision of the SS and its Security Service as the core of a comprehensive new system of policing and control... on 9 March 1933, the two men took over the Bavarian police service, making the political section autonomous and moving SS Security Service personnel into some of the key posts. They went on to take over the political police service in one federated state after another, with the backing of the centralizing Reich Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick." (30)

Walter Schellenberg who was able to observe both men at work has pointed out that Heydrich was the "hidden pivot around which the Nazi regime revolved.... He was far superior to all his political colleagues and controlled them as he controlled the vast intelligence machine of the SD." (31) However, his wife, Lina Heydrich claimed that he an an inferiority complex: "His apparent arrogance was no more than self-protection. Even with me he expressed no kind word, no word of tenderness". (32)

Himmler was subordinate to the Sturm Abteilung (SA). This brought him into conflict with the Ernst Roehm. Himmler continued to build up his power base by establishing his own secret civilian security organization, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and placed Reinhard Heydrich at its head.

In 1932 Himmler sold the house and poultry farm in Waldtrudering and moved into a flat close to Hitler's apartment. He also purchased a large villa at Gmund on the Tegernsee, a lake south-east of Munich enclosed by mountains. Marga Himmler established herself there with Gudrun, whom they called "Puppi". The following year they adopted a boy named Gerhard von Ahe. He was the son of Kurt von der Ahe, a senior figure in the SS, who had been killed in Berlin.

Reichstag Fire

On 27th February, 1933, someone set fire to the Reichstag. Several people were arrested including a leading, Georgi Dimitrov, general secretary of the Comintern, the international communist organization. Dimitrov was eventually acquitted but a young man from the Netherlands, Marianus van der Lubbe, was eventually executed for the crime. As a teenager Lubbe had been a communist and Hermann Goering used this information to claim that the Reichstag Fire was part of a KPD plot to overthrow the government. (33)

Adolf Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". KPD candidates in the election were arrested and Goering announced that the Nazi Party planned "to exterminate" German communists. Thousands of members of the Social Democrat Party and KPD were arrested and sent to Germany's first concentration camp at Dachau, a village a few miles from Munich. Himmler was placed in charge of the operation, whereas Theodor Eicke became commandant of the first camp and eventually took overall control of the system.

Gestapo

On 26th April, 1933, Hermann Göring established the Prussian Secret State Police (Gestapo). He appointed Rudolf Diels as his deputy. "The same day a decree created a State police office in each district of Prussia, subordinate to the central Service in Berlin. The Gestapo... now had a branch in every district, but its power did not yet exceed the boundaries of Prussia. The purge was complete, not only in the police but also in the magistrature and among the State officials. A law was passed that... allowed the dismissal of officials and anti-Fascist judges, Jews, or those who had belonged to Left Wing organizations." (34)

The organization was gradually enlarged and reorganzed so that it could "deal with political police tasks in parallel with or instead of normal police authorities". The following year Göring decided to form an alliance with Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich. On 24th April 1934, Göring appointed Himmler Inspector of the Secret State Police and Heydrich its commander. Now the whole police apparatus was firmly in SS hands. It has been argued by Alan Bullock, that Göring had taken this decision in order to obtain an ally against Ernst Röhm and the Sturm Abteilung (SA). (35)

In May 1933, Himmler met Oswald Pohl and told him he was looking for an officer to take over the administrative and financial side of the SS. At first Pohl rejected the offer as he was happy in the navy and headed a staff of over 500 hundred men at Kiel. Pohl later wrote: "Himmler became very insistent and wrote me one letter after another urging that I take over the administrative organisation of the SS. In December 1933 and January 1934, he invited me to Berlin and Munich, and showed me the whole SS administrative set-up and the many complex problems that were involved. It was only in February 1934, after I saw what a big job was in store for me, that I finally accepted."

Pohl joined Himmler's personal staff as chief of the administrative section. "When I took over my office, the SS was a comparatively small organisation, like a union, with a group here and there in various towns and cities. I started by installing administrative commands in various key cities, and I selected personnel who would be fit for their jobs. I inaugurated schools that taught these administrative officials for a few weeks before they were dispatched to take over my branch offices all over Germany. I achieved a sound administration in the SS, with orderly bookkeeping and financial sections." (36)

Adrian Weale, the author of The SS: A New History (2010): "Before January 1933, much of the SS's funding had come from membership dues, with occasional subsidies from party headquarters for special projects, but as it began to take over state functions, it increasingly became eligible for state funding. It was in this area that Pohl really made his mark. Despite the supposedly revolutionary nature of the National Socialist government, expenditure still had to be justified, budgets formulated and fiscal probity maintained to the satisfaction of both the civil service and the party. Pohl, drawing on his long experience in naval administration, succeeded in achieving all of this. In addition, he established relationships between his office and the various departments and ministries on whom the SS depended for its budget: the party treasury, the Finance Ministry, the Ministry of the Interior; the Army Ministry and so forth." (37)

Heinrich Himmler & Ernst Röhm

By 1934 Adolf Hitler appeared to have complete control over Germany, but like most dictators, he constantly feared that he might be ousted by others who wanted his power. To protect himself from a possible coup, Hitler used the tactic of divide and rule and encouraged other leaders such as Himmler, Hermann Goering, Joseph Goebbels, and Ernst Röhm to compete with each other for senior positions.

Albert Speer pointed out in his book, Inside the Third Reich (1970): "After 1933 there quickly formed various rival factions that held divergent views, spied on each other, and held each other in contempt. A mixture of scorn and dislike became the prevailing mood within the party. Each new dignitary rapidly gathered a circle of intimates around him. Thus Himmler associated almost exclusively with his SS following, from whom he could count on unqualified respect... As an intellectual Goebbels looked down on the crude philistines of the leading group in Munich, who for their part made fun of the conceited academic's literary ambitions. Goering considered neither the Munich philistines nor Goebbels sufficiently aristocratic for him and therefore avoided all social relations with them; whereas Himmler, filled with the elitist missionary zeal of the SS felt far superior to all the others." (38)

One of the consequences of this policy was that these men developed a dislike for each other. Roehm was particularly hated because as leader of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) he had tremendous power and had the potential to remove any one of his competitors. Himmler asked Reinhard Heydrich to assemble a dossier on Roehm. Heydrich, who also feared him, manufactured evidence that suggested that Röhm had been paid 12 million marks by the French to overthrow Hitler.

Hitler liked Ernst Röhm and initially refused to believe the dossier provided by Heydrich. Röhm had been one of his first supporters and, without his ability to obtain army funds in the early days of the movement, it is unlikely that the Nazis would have ever become established. The SA under Röhm's leadership had also played a vital role in destroying the opposition during the elections of 1932 and 1933. However, Hitler had his own reasons for wanting Röhm removed. Powerful supporters of Hitler had been complaining about Röhm for some time. Generals were afraid that the Sturm Abteilung (SA), a force of over 3 million men, would absorb the much smaller German Army into its ranks and Röhm would become its overall leader.

Industrialists such as Albert Voegler, Gustav Krupp, Alfried Krupp, Fritz Thyssen and Emile Kirdorf, who had provided the funds for the Nazi victory, were unhappy with Roehm's socialistic views on the economy and his claims that the real revolution had still to take place. Many people in the party also disapproved of the fact that Röhm and many other leaders of the SA were homosexuals.

Night of the Long Knives

Adolf Hitler was also aware that Roehm and the SA had the power to remove him. Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler played on this fear by constantly feeding him with new information on Roehm's proposed coup. Their masterstroke was to claim that Gregor Strasser, whom Hitler hated, was part of the planned conspiracy against him. With this news Hitler ordered all the SA leaders to attend a meeting in the Hanselbauer Hotel in Bad Wiesse.

Himmler along with his loyal assistants, Reinhard Heydrich, Kurt Daluege and Walter Schellenberg, drew up a list of people outside the SA that they wanted killed. The list included Gregor Strasser, Kurt von Schleicher, Hitler's predecessor as chancellor, and Gustav von Kahr, who crushed the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. Louis L. Snyder argues: "Hitler later alleged that his trusted friend Roehm had entered a conspiracy to take over political power. The Führer was told, possibly by one of Roehm's jealous colleagues, that Roehm intended to use the SA to bring a socialist state into existence... On June, 1934... Hitler came to his final decision to eliminate the socialist element in the party. A list of hundreds of victims was prepared." (38) This became known as the Night of the Long Knives.

On 29th June, 1934. Hitler, accompanied by Theodor Eicke and selected members of the Schutzstaffel (SS), arrived at Bad Wiesse, where he personally arrested Ernst Röhm. During the next 24 hours 200 other senior SA officers were arrested on the way to the meeting. Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Röhm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Röhm, you are under arrest. Röhm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Röhm under police guard. Röhm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Röhm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic." (39)

A large number of the SA officers were shot as soon as they were captured but Adolf Hitler decided to pardon Röhm because of his past services to the movement. However, after much pressure from Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler, Hitler agreed that Röhm should die. Himmler ordered Theodor Eicke to carry out the task. Eicke and his adjutant, Michael Lipppert, travelled to Stadelheim Prison in Munich where Röhm was being held. Eicke placed a pistol on a table in Röhm's cell and told him that he had 10 minutes in which to use the weapon to kill himself. Röhm replied: "If Adolf wants to kill me, let him do the dirty work."

According to Paul R. Maracin, The author of The Night of the Long Knives: Forty-Eight Hours that Changed the History of the World (2004): "Ten minutes later, SS officers Michael Lippert and Theodor Eicke appeared, and as the embittered, scar-faced veteran of verdun defiantly stood in the middle of the cell stripped to the waist, the two SS officers riddled his body with revolver bullets." (40) Eicke later claimed that Röhm fell to the floor moaning "Mein Führer". Three days after the purge Eicke was appointed Inspector of Concentration Camps and head of Death's Head Units. He was also promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General (SS-Gruppenfuehrer). According to Louis L. Snyder, the next day, Otto Dietrich, Press Chief of the NSDAP, "gave a blood-curdling account of the slaughter to the press. He described Hitler's sense of shock at the moral degeneracy of his oldest comrades." (41)

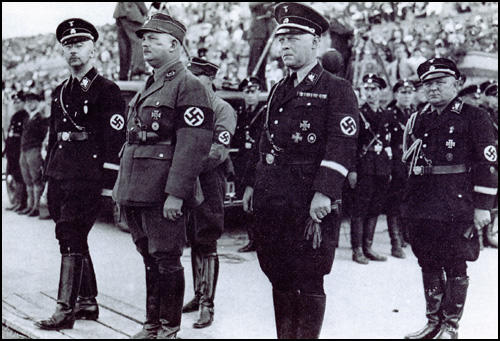

Three weeks after the Night of the Long Knives the Schutzstaffel (SS) was given independent status and no longer under the control of the SA. As a result of this purge the SS was now the principal instrument of internal rule in Germany. Now that Himmler was leader of his own independent SS, he could expand the organization. By the end of 1934 it had 400,000 members. Eventually, Himmler came to the conclusion that the mass recruitment which had taken place was very damaging to the elite status of the SS and so in 1935 over 200,000 SS men were discharged on moral, racial and physical grounds. Himmler now introduced a complex five year enrolment procedure. Having been declared physically and racially suitable for SS membership, an eighteen-year-old youth became an applicant (bewerber). The following year he became a candidate (anwärter). At the end of his probationary period he swore the oath of alliance to Adolf Hitler. At twenty-one he became liable for military service which lasted two years. It was only on his return to civilian life that he became a full SS man.

As an SS man he would serve in SS1 until he was twenty-five, then SS2 until thirty-five, when he became a member of the SS Reserve. The typical part-time member of the SS gave up one evening a week for ideological work and training. One afternoon, usually Wednesday or Saturday, was set aside for physical training and sport. One weekend in each month an SS man had to spend Saturday afternoon and Sunday on military training, important elements of which were drill, crowd control and shooting.

This smart and disciplined para-military force enabled the Nazi Party to maintain a large auxiliary police force at nominal cost. The SS could be called out at short notice in case of a national emergency such as an anti-Nazi putsch, a demonstration or a trade union dispute. The SS were also used to help the police with crowd control and security arrangements for a visit by Hitler or any other prominent member of the Nazi Party. SS headquarters in Berlin would summon SS men to duty with a printed postcard. An SS man's employee was forbidden by law to prevent or hinder his employee from responding to such a summons.

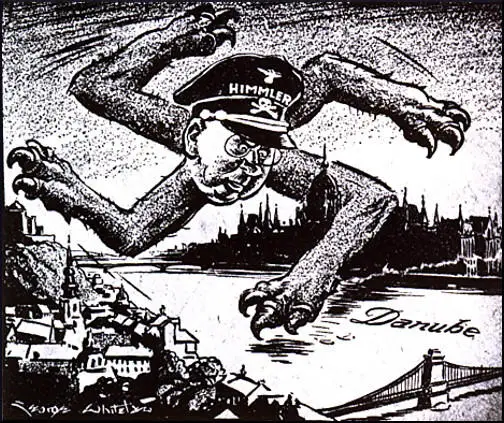

Himmler's Growing Power

On 17th June, 1936, Hitler designated Himmler as head of the unified police system of the Third Reich. He was also put in charge of the Gestapo. "Essentially the Gestapo were policemen, but they were the instruments of Nazi methods which allowed and encouraged terror to gain and keep control of the state and the people... As Nazi power spread so did the fearsome reputation of the Gestapo. Backed by the system of concentration camps and by his right under the law to extract confessions by beating, the Gestapo man in the leather overcoat and dark, snap-brim hat became a figure of terror." (42)

Jacques Delarue, the author of The Gestapo (1962) has argued that Himmler imposed on the Gestapo the structure developed with the Schutzstaffel (SS): "Himmler, grand master of the S.S. transposed some of the principles of the Black Order to organize the Gestapo. The strict hierarchy was progressively modeled on that of the S.S., even reproducing it completely as soon as the members of the Gestapo received S.S. rank on assimilation. The partitioning of powers was reinforced by the protection of secrecy. Discretion was one of the basic principles of S.S. discipline. It constituted one of the essential bases of the Gestapo which Himmler, as he had done with the S.S. turned into an enclosed world, of which no one had the right to catch the least glimpse and about which it was forbidden to utter any criticism." (43)

Concentration Camps

Himmler was in overall control of the concentration camps in Germany. Hermann Langbein, the author of Against All Hope: Resistance in the Nazi Concentration Camps 1938-1945 (1992) has pointed out: "National Socialism replaced democratic institutions with a system of command and obedience, the so-called Fuhrer principle, and it was this system that the Nazis installed in their concentration camps. It goes without saying that any command by a member of the SS had to be unconditionally carried out by all prisoners. Refusal or hesitation was liable to lead to a cruel death. The camp administration not only saw to it that every command was carried out, but also held inmates assigned to certain jobs responsible for completing them. In this way it facilitated its own work and was also able to play one prisoner off against another.... Each unit housing prisoners, whether a barrack or a brick building, was called a block. The camp administration held a senior block inmate (Blockdltester) responsible for enforcing discipline, keeping order, and carrying out all commands. If a dwelling unit was divided into rooms, a senior block inmate was assisted by senior barracks inmates and their staff. A senior camp inmate (Lageraltester) was responsible for the operation of the entire camp, and it was he who proposed the appointment of senior block inmates to the officer-in-charge." (44)

Langbein, who was an inmate in Dachau, explained that each work group was headed by a capo (trusty). "The capo himself was exempted from work, but he had to see to it that the required work was done by his underlings. Capos, senior block inmates, and senior camp inmates were identified by an armband with the appropriate inscription. These armband wearers, as they were generally called, were under the protection of the camp administration, often enjoyed extensive privileges, and as a rule had unlimited power over those under them. This is to be taken literally, for if an armband wearer killed an underling, he did not (with a few exceptions) have to answer to anyone, provided a timely report of the death was made and the roll call was corrected. An ordinary prisoner was completely at the mercy of his capo and senior block inmate."

Heinrich Himmler argued that: "These approximately 40,000 German political and professional criminals... are my 'noncommissioned officer corps' for this whole kit and caboodle. We have appointed so-called capos here; one of these is the supervisor responsible for thirty, forty, or a hundred other prisoners. The moment he is made a capo, he no longer sleeps where they do. He is responsible for getting the work done, for making sure that there is no sabotage, that people are clean and the beds are of good construction.... So he has to spur his men on. The minute we're dissatisfied with him, he is no longer a capo and bunks with his men again. He knows that they will then kill him during the first night."

Inmates had to wear a coloured symbol to indicate their category. This included political prisoners (red), convicts (greens), Jews (yellow), homosexuals (pink), Jehovah's Witnesses (violet) and what the Nazis described as anti-socials (black). The anti-social group included gypsies and prostitutes. The Schutzstaffel (SS) preferred those with a criminal record to be capos. As Hermann Langbein has pointed out: "As a rule the SS bestowed armbands on prisoners they could expect to be willing tools in return for their privileged status. As soon as German convicts arrived in the camps the SS preferred them to morally stable men."

Himmler & Hedwig Potthast

Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) has claimed that Himmler was jealous that the two men under him in the Schutzstaffel (SS), Reinhard Heydrich and Karl Wolff, both had attractive wives. Himmler spent very little time with his wife. Lina Heydrich suggested that Himmler was embarrassed by her appearance: "Size 50 knickers, that's all there was to her." Bella Fromm, a journalist commented in July 1937 she saw Himmler with his "dirty-blonde, insipid, fat wife" and "the pleasures of the table are apparently about the pleasures she gets, since Himmler keeps her at home." (45)

In 1939 Heinrich Himmler began an affair with his young secretary, Hedwig Potthast. The couple set up home in Mecklenburg. Hedwig gave birth to a son, Helge (born 1942) and a daughter, Nanette Dorothea (born 1944). Lina Heydrich commented that Himmler become more relaxed and human as a result of his relationship with Hedwig. Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991): "All testimony suggests that the relationship between Himmler and Häschen (Hedwig) was a loving one on both sides. A girl who joined Himmler's secretarial staff two years later and lived for long periods in his special train noticed that he kept Häschen's photograph in his desk and often, when he was working, took it out to look at it.... At one time, she said, he had wanted to divorce Marga to marry her. Häschen had stopped him for Marga's sake. It is more likely perhaps that he stopped himself for the reasons he had refused Wolff permission to divorce. There must be no malicious gossip around the person of the Reichsfuhrer; he above all had to set an example of decency." (46)

Although separated from his wife, Himmler remained close to his daughter, Gudrun Himmler, who he phoned every few days and wrote to her at least once a week. Himmler adored his young, blue-eyed, blonde-haired daughter and would often take her to official state functions. In 1941 he even took his daughter to visit the Dachau Concentration Camp. Gudrun wrote in her diary: "Today, we went to the SS concentration camp at Dachau. We saw everything we could. We saw the gardening work. We saw the pear trees. We saw all the pictures painted by the prisoners. Marvelous. And afterwards we had a lot to eat. It was very nice." According to Stephan Lebert, the author of My Father' s Keeper: Children of Nazi Leaders - An Intimate History of Damage and Denial (2001): "At fourteen... she cut out every picture of him from the newspapers and glued them into a large scrapbook" (47)

Second World War

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Himmler was appointed as a Commissar for the Consolidation of German Nationhood. Himmler devised methods of mass murder based on a rationalized extermination process. His main task was to eliminate "racial degenerates" that Hitler believed stood in the way of German's regeneration. The SS also followed the German Army into the Soviet Union where they had the responsibility of murdering Jews, gypsies, communists and partisans.

After the war Lieutenant Colonel Richard Schulze-Kossens, who fought with the Leibstandarte-SS Adolf Hitler in Poland in 1939 defended his troops in this action: "Let me say as a soldier I condemn all crimes regardless of who committed them, whether by us or by others, and that includes the crimes committed against captured SS men after the capitulation. But I make no reproaches in that respect. I am not recriminating, I only want to say that in war, amongst the mass of soldiers, there are always elements who develop criminal tendencies, and I can only condemn them. I would not say that the Waffen-SS was typically criminal, but there are well-known incidents. I don't want to excuse anything, but I must say one thing which is, that it is natural in war, during hot and heavy fighting, for young officers to sometimes lose their nerve." (48)

In August 1941, Himmler and Karl Wolff observed a mass execution near Minsk, that had been organised by Arthur Nebe. According to Wolff, Himmler noticed a tall, blond, blue-eyed man of about twenty whom he engaged in conversation. Himmler asked the man if both his parents were Jews. When he replied "Yes" he followed up with "Do you have any ancestors who were not Jews?" When the man said "No" he replied: "Then I can't help you."

Standing close to the pit, Himmler became increasingly distressed as the shooting commenced. According to Wolff: "After many volleys, I could see that Himmler was trembling. He ran his hand across his face and swayed... His face was almost green... He immediately threw up." Himmler complained that "a piece of brain just splattered in my face". After the killing was over, Himmler made a speech to the men in which he told them to "see it through". Wolff claims that Himmler told Nebe to "devise a less gruesome means of mass execution than simply shooting people." (49)

In February 1942, Oswald Pohl took control of the administration of the concentration camps. Pohl clashed with Theodor Eicke over the way the camps should be run. According to Andrew Mollo, the author of To The Death's Head: The Story of the SS (1982): "Pohl insisted on better treatment for camp inmates, and SS men were forbidden to strike, kick or even touch a prisoner. Inmates were to be better housed and fed, and even encouraged to take an interest in their work. Those who did were to be trained and rewarded with their freedom. There was a small reduction in the number of cases of maltreatment, but food and accommodation were still appalling, and in return for these 'improvements' prisoners were still expected to work eleven hours per day, six or seven days a week." (50)

War Production

Pohl came under pressure from Albert Speer to increase production at the camps. Pohl complained to Himmler: "Reichsminister Speer appears not to know that we have 160,000 inmates at present and are fighting continually against epidemics and a high death-rate because of the billeting of the prisoners and the sanitary arrangements are totally inadequate." In a letter written on 15th December, 1942, Himmler suggested an improvement in the prisoner's diet: "Try to obtain for the nourishment of the prisoners in 1943 the greatest quantity of raw vegetables and onions. In the vegetable season issue carrots, kohlrabi, white turnips and whatever such vegetables there are in large quantity and store up sufficient for the prisoners in the winter so that they had a sufficient quantity every day. I believe we will raise the state of health substantially thereby." (51)

As the war progressed Adolf Hitler became greatly concerned about the problems of production. Himmler informed Hitler that a growing number of prisoners were placed at the disposal of the armaments industry. According to Hermann Langbein, the author of Against All Hope: Resistance in the Nazi Concentration Camps 1938-1945 (1992): Auschwitz's four rapidly erected crematories with built-in gas chambers made such killing possible with the smallest expenditure of guards and service personnel. But because the arms industry required ever more workers, those destined for extermination were subjected to a selection process, something that was not done in the extermination camps of eastern Poland." (52)

Himmler instructed all camp commandants to lower the mortality rate substantially. On 20th January 1943, wrote: "I shall hold the camp commandant personally responsible for doing everything possible to preserve the manpower of the prisoners." Himmler told Oswald Pohl: "I believe that at the present time we must be out there in the factories personally in unprecedented measure in order to drive them on with the lash of our words and use our energy to assist on the spot. The Führer is counting heavily on our production and our help and our ability to overcome all difficulties, just hurl them overboard and simply produce. I ask you and Richard Glucks (head of concentration camp inspectorate) with all my heart to let no week pass by when one of you does not appear unexpectedly at this or that camp and goad, goad, goad." (53)

In a speech made on 4th October, 1943, to members of the Schutzstaffel (SS), Himmler argued: "One basic principle must be the absolute rule for the SS men - we must be honest, decent, loyal, and comradely to members of our own blood and to nobody else. What happens to a Russian or to a Czech does not interest me in the slightest. What the nations can offer in the way of good blood of our type we will take, if necessary by kidnapping their children and raising them here with us. Whether nations live in prosperity or starve to death interests me only so far as we need them as slaves for our culture; otherwise, it is of no interest to me. Whether ten thousand Russian females fall down from exhaustion while digging an antitank ditch interests me only so far as the antitank ditch for Germany is finished. We shall never be rough and heartless when it is not necessary, that is clear. We Germans, who are the only people in the world who have a decent attitude toward animals, will also assume a decent attitude toward these human animals."

He added: "I also want to talk to you, quite frankly, on a very grave matter. Among ourselves it should be mentioned quite frankly, and we will never speak of it publicly. Just as we did not hesitate on 30 June 1934 to do the duty we were bidden and stand comrades who had lapsed up against the wall and shoot them, so we have never spoken about it and will never speak of it. It was that tact which is a matter of course and which I am glad to say, inherent in us, that made us never discuss it among ourselves, nor speak of it. It appalled everyone, and yet everyone was certain that he would do it the next time if such orders are issued and if it is necessary. I mean the evacuation of the Jews, the extermination of the Jewish race.... Most of you must know what it means when one hundred corpses are lying side by side, or five hundred, or one thousand. To have stuck it out and at the same time - apart from exceptions caused by human weakness - to have remained decent fellows, that is what has made us hard. This is a page of glory in our history which has never been written and is never to be written, for we know how difficult we should have made it for ourselves, if with the bombing raids, the burdens and the deprivations of war we still had Jews today in every town as secret saboteurs, agitators, and troublemakers. We would now probably have reached the 1916-1917 stage when the Jews were still in the German national body." (54)

Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "Himmler expanded the SS from three to thirty-five divisions, until it rivaled the Wehrmacht itself. Made Minister of the Interior on August 25, 1943, he strengthened his grip on the civil service and the courts. Meanwhile, he enlarged the concentration camps and the extermination camps, organized a supply of expendable labor, and the authorized pseudomedical experiments in the camps... On July 21, 1944, Hitler made him supreme commander of the Volkssturm defending the German capital and the chief of the Werwolf unit that was expected to carry on a last-ditch fight in the Bavarian mountains." (55)

By June 1944 the SS had over 800,000 members: Hitler's Body Guard (200,000) Waffen (594,000) and Death Head Units (24,000). In April 1944 Oswald Pohl issued orders to camp commanders: "Work must be, in the true sense of the world, exhausting in order to obtain maximum output... The hours of work are not limited. The duration depends on the technical structure of the camp and the work to be done and is determined by the camp Kommandant alone." One inmate of Auschwitz complained that Pohl was guilty of "the systematic and implacable urge to use human beings as slaves and to kill them when they could work no more."

Heavy bombing of the camps further damaged production. Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) points out that Himmler suggested a possible solution to the problem: "Himmler urged Pohl to build factories for the production of war materials in natural caves and underground tunnels immune to enemy bombing, and instructed him to hollow out workshop and factory space in all SS stone quarries, suggesting that by the summer of 1944 they should have ... the greatest possible number of such 'uniquely bomb-proof work sites'... Pohl's Works' Department chief, Brigadeführer Hans Kammler, succeeded in creating underground workshops and living quarters from a cave system in the Harz mountains in central Germany." (56)

Himmler attempts Negotiated Peace

Himmler was put in charge of the German Army facing the advancing United States Army. In January, 1945, he was switched to face the advancing Red Army in the east. Unable to halt the decline in fortunes of the German forces, Himmler became convinced that Germany needed to seek peace with Britain and the United States. In March, 1945, Himmler had a meeting with Joseph Goebbels. He recorded in his diary: "Himmler summarises the situation correctly when he says that his mind tells him that we have little hope of winning the war militarily but instinct tells him that sooner or later some political opening will emerge to swing it in our favour. Himmler thinks this more likely in the West than the East. He thinks that England will come to her senses, which I rather doubt. As his remarks show, Himmler is entirely Western-oriented; from the East he expects nothing whatsoever. I still think that something is more likely to be achieved in the East since Stalin seems to me more realistic than the trigger-happy Anglo-American (Roosevelt)." (57)

General Walter Schellenberg suggested to Himmler at the beginning of 1945 that he should open negotiations with the Western Powers. Himmler was at first reluctant to go against Adolf Hitler but when the Swedish internationalist Count Folke Bernadotte, arrived in Berlin in February to discuss the release of Norwegian and Danish prisoners on behalf of the Swedish Red Cross, he agreed to a meeting. However, Himmler could not make up his mind to speak out. He did agree to accompany Schellenberg to another meeting with Bernadotte in Lübeck on 23rd April, 1945.

Himmler told Bernadotte that Hitler intended to commit suicide in the next few days: "In the situation that has now arisen I consider my hands free. I admit that Germany is defeated. In order to save as great a part of Germany as possible from a Russian invasion I am willing to capitulate on the Western Front in order to enable the Western Allies to advance rapidly towards the east. But I am not prepared to capitulate on the Eastern Front." Bernadotte passed this message to onto Winston Churchill and Harry S. Truman but they rejected the idea, insisting on unconditional surrender.

The Death of Heinrich Himmler

On 28th April the negotiations were leaked to the press. Hanna Reitsch was with Hitler when he heard the news: "His colour rose to a heated red and his face was unrecognizable... After the lengthy outburst, Hitler sank into a stupor, and for a time the entire bunker was silent." Hitler ordered Himmler's arrest. In an attempt to escape Himmler now took the name and documents of a dead village policeman. Although in heavy disguise, Himmler was arrested by a British army officer in Bremen on 22nd May. Before he could he interrogated, Himmler committed suicide by swallowing a cyanide capsule.

The American journalist, Ann Stringer, gave Himmler's wife the news of his death: "Frau Margarete Himmler maintained today that she was still proud of her infamous husband and shrugged away the world's hatred of the dead Gestapo chief with the calm observation that no one loves a policeman. When I told her that husband Heinrich had been captured and had died from his own dose of poison, Frau Himmler showed absolutely no emotion. She sat, hands folded in her lap, and merely shrugged her shoulders. Until then she had not known what had happened to Himmler since he last telephoned her from Berlin around Easter while she was at their home near Munich. When first captured by the Fifth Army she had claimed a weak heart and internment camp officials, fearful of a heart attack, never told her of her husband's death. But even when I told her that Himmler was buried in an unmarked grave Frau Himmler showed no surprise, no interest. It was the coldest exhibition of complete control of human feeling that I have ever witnessed." (58)

Gudrun Himmler, refused to believe that her father had committed suicide. She pointed out that his body was photographed before he was cremated: "In those pictures he looks more as though he was about to inspect a parade. He had a typical way of placing his hands on those occasions, and I don't accept that he'd hold his hands that way if, as it was reported, he was biting into a poison capsule. I believe that picture shows him really inspecting a parade. To me it's a retouched photo from when he was alive." (59)

Primary Sources

(1) Hugh Thomas, The Unlikely Death of Heinrich Himmler (2001)

Despite the inherent advantage of his father being headmaster, Himmler never achieved much academically, even though his father employed a personal tutor. His phenomenal memory served him well in history and geography. However, he failed to get in the top third of his graduation class, and passed his much-deferred Abitur examination with just two days to spare before taking up his place at technical college. Nor did he shine in music. He started learning to play the piano, but had no real talent for it, and was eventually persuaded to give it up. When war broke out in 1914, Himmler became inflamed with the patriotic zeal of the times and two years later his father unsuccessfully attempted to get him a commission. His diaries are drenched in the sentiments of the Kaiser's Intellectual Brigade of Guards, who believed in the intellectual superiority of the martial elite, and fervently expounded the concepts of the Pan-Germanic League that believed Germany should encompass all. (page 20)

(2) Heinrich Himmler, diary entry (24th November, 1921)

A real man will love a woman in three ways - first as a dear child who must be admonished, perhaps even punished when she is foolish... secondly he will love her as a wife and a dear comrade who helps him fight in the struggle of life, always at his side but never dampening the spirit... thirdly he will love her as the wife whose feet he longs to kiss and who gives him the strength never to falter, even in the worst strife, in the strength that she gives thanks to her child-like purity.

(3) Heinrich Himmler, diary entry (5th February, 1922)

We discussed the danger of such things. I have experienced it, one lay so closely together, by couples, body to body, hot human being by human being, one catches on fire and has to summon all one's rational faculties. The girls arc then so far gone they no longer know what they are doing. It is the hot, unconscious longing of the whole individual for the satisfaction of a frightfully powerful natural drive. That is why it is also so dangerous for the man and involves such responsibility. One could do as one wants with the helpless girls, yet one has enough to do to struggle with oneself. I am indeed sorry for the girls.

(4) Ernst Hanfstaengel, Hitler: The Missing Years (1957)

He (Heinrich Himmler) had a pale, round, expressionless face, almost Mongolian, and a completely inoffensive air. Nor in his early years did I ever hear him advocate the race theories of what he was to become the most notorious executive.

He studied to become a veterinary surgeon, although I doubt if he had ever become fully qualified. It was probably only part of the course he had taken as an agricultural administrator, but, for all I know, treating defenceless animals may have tended to develop that indifference to suffering which was to become his most frightening characteristic.

(5) Walter Dornberger, V2 (1952)

He (Heinrich Himmler) looked to me like an intelligent elementary schoolteacher, certainly not a man of violence ... Under a brow of average height, two grey-blue eyes looked at me, behind glittering pince-nez, with an air of peaceful interrogation. The trimmed moustache below the straight, well-shaped nose traced a dark line on his unhealthy, pale features. The lips were colourless and very thin. Only the conspicuous receding chin surprised me. The skin of his neck was flaccid and wrinkled. With a broadening of his constant set smile, faintly mocking and sometimes contemptuous about the corners of the mouth, two rows of excellent white teeth appeared between the thin lips. His slender, pale, almost girlishly soft hands, covered with veins, lay motionless on the table throughout our conversation....

Himmler possessed the rare gift of attentive listening. Sitting back with legs crossed, he wore throughout the same amiable expression. His questions showed that he unerringly grasped what the technicians told him out of the wealth of their knowledge. The talk turned to war and the important questions in all our minds. He answered calmly and candidly. It was only at rare moments that, sitting with his elbows resting on the arms of the chair, he emphasised his words by tapping the tips of his fingers together. He was a man of quiet unemotional gestures. A man without words.

(6) Hugh Thomas, The Unlikely Death of Heinrich Himmler (2001)

The pattern of a lifetime was established. He was a man of no outstanding intellectual gifts other than his memory, and no physical attraction, who set out to dominate the lives and minds of others. He was goaded by an unpleasant combination of ambition and officiousness that he disguised as high moral purpose. That he succeeded so well, then in a modest way, but later on a scale which brought disaster to mankind, must be attributed partly to hereditary make-up, and partly to the indoctrination of his father, which left him with exaggerated ideas of his own importance. This episode shows an outstandingly pompous man, middle-aged at 24.

(7) Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (1970)

After 1933 there quickly formed various rival factions that held divergent views, spied on each other, and held each other in contempt. A mixture of scorn and dislike became the prevailing mood within the party. Each new dignitary rapidly gathered a circle of intimates around him. Thus Himmler associated almost exclusively with his SS following, from whom he could count on unqualified respect. Goering also had his band of uncritical admirers, consisting partly of members of his family, partly of his closest associates and adjutants. Goebbels felt at ease in the company of literary and movie people. Hess occupied himself with problems of homeopathic medicine, loved chamber music, and had screwy but interesting acquaintances.

As an intellectual Goebbels looked down on the crude philistines of the leading group in Munich, who for their part made fun of the conceited academic's literary ambitions. Goering considered neither the Munich philistines nor Goebbels sufficiently aristocratic for him and therefore avoided all social relations with them; whereas Himmler, filled with the elitist missionary zeal of the SS felt far superior to all the others. Hitler, too, had his retinue, which went everywhere with him. Its membership, consisting of chauffeurs, the photographer, his pilot, and secretaries, remained always the same.

(8) Konrad Heiden, Der Führer – Hitler's Rise to Power (1944)

The post-war generation now begins to assume prominence in the party. Himmler was the first party leader who had been too young to serve in the World War. Born in Munich in 1900, he grew up in Landshut, where Gregor Strasser later lived. He attended the gymnasium, and like all German gymnasiasts of that day, was given an opportunity to become an officer. He spent the last year of the World War as an ensign (aspirant to the officer's career) in a Bavarian regiment, but never reached the front...

Himmler is an excellent example of what a task can make of a man. He had a task of the first order to solve, and the task made him; to a nature mediocre at best it gave a weightiness which the apparatus that grew up around him helped him to bear. Men who combine the gift of creation or leadership with deep insight or independent judgment are always rare; in the National Socialist Movement they can be counted on the fingers; Himmler in any case is not one of them. His great qualities, infrequent in his milieu, are industry, precision, thoroughness. It is a quality inherent in a body of men working for a common purpose that great results can be achieved by the men who are not great. A preponderance of strong personalities can even force a split, and only through the addition of average qualities can an efficient machine be built up. Himmler is the living, actual proof of Hitler's thesis, "that the strength of a political party lies, not in having single adherents of outstanding intelligence, but in disciplined obedience. A company of two hundred men of equal capabilities would in the long run be more difficult to discipline than a group in which one hundred and ninety are less capable and ten are of greater abilities".

In the National Socialist machine Himmler is a wire activated by the electric current, connecting important parts. He looks like the caricature of a sadistic school-teacher, and this caricature conceals the man like a mask. If one takes away the pince-nez and uniform, there is revealed, under a narrow forehead, a look of curious objectivity. Apart from pose and calling, he gives the impression of a certain courtesy - even modesty. But this objectivity is of that frightful sort that can look unmoved on the most grisly of horrors. A demonic will to power has been attributed to him; in truth, he, more than any other of the first rank of his party, has been guided by devotion to the cause, and compared to others he might be considered a model of personal selflessness. He is married, his private life is unassuming. He loves flowers and birds, yet this offers no contradiction to his political role; personally he is almost without demands. More than anyone else in this circle, he feels that he is only a part of the whole embodied in the person of his supreme leader; his passion for race and race-building arises from a deep contempt of the individual, including himself. He has found classic formulas for the creed of the armed intellectual - that the State is all, the individual nothing. He takes the doctrine of "you are nothing, your people are everything", more seriously than almost anyone else in the movement, and for that reason Hitler took this man more seriously than many others who were more intelligent.

Himmler understood with his heart when his Fuhrer demanded that the party must become the racial elite of Germany, the party of the ruling minority. But by the party was meant Hitler's party, which grew out of the unbridled National Socialist mass and raised itself above the mass; Himmler saw his own S.S. as the motive force of this special party. "We are not more intelligent than two thousand years ago," he said to his men in 1931. "The military history of antiquity, the history of the Prussian Army two or three hundred years ago - again and again we see that wars are waged with men, but that every leader surrounds himself with an organization of men of special quality when things are at their worst and hardest; that is the guard. There has always been a guard; the Persians, the Greeks, Caesar, Old Fritz,' Napoleon, all had a guard, and so on up to the World War; and the guard of the new Germany will be the S.S. The guard is an elite of specially chosen men."

Chosen average men in positions of mastery. That is the meaning of the S.S., which represents the model of National Socialist education. These men are not - and are not supposed to be - great individuals, but "good material" for the fabrication of a race, as Chamberlain put it. Therefore, their "honour is loyalty"; that is, obedience towards the few who really rule and lead. "Few flames burn in Germany," Goebbels once said of these top personalities, naturally counting himself among them; the rest are only illumined by their glow" - he wrote these words of contempt in his diary after returning from a meeting of party officials (1932), where he had seen the good material assembled.

The S.S. was stamped forever by the reason for its founding: Hitler's need to control an undisciplined party by founding a new party. The National Socialist despises his fellow-Germans, the S.A. man the other National Socialists, the S.S. man the S.A. men. His task is to supervise and spy on the whole party for his leader. The first service code of the S.S. lists among its tasks protection of the Fuhrer, a promotion of understanding within the ranks, information service. The last two terms mean espionage within and outside the party.

In 1930 Hitler surprised a circle of his friends by asking them if they had read the just-published autobiography of Leon Trotsky, the great Jewish leader of the Russian Revolution, and what they thought of it. As might have been expected, the answer was: "Yes... loathsome book... memoirs of Satan... "To which Hitler replied: `Loathsome? Brilliant! I have learned a great deal from it, and so can you." Himmler, however, remarked that he had not only read Trotsky but studied all available literature about the political police in Russia, the Tsarist Ochrana, the Bolshevist Cheka and G.P.U.; and he believed that if such a task should ever fall to his lot, he could perform it better than the Russians.

With this in mind he drilled his troop, imbued it with his Fuhrer's arrogance and contempt of humanity, thus arming its men with the moral force to massacre their own people as well as foreigners, and to regard this as absolutely necessary. At a time when the party still meant nothing, Himmler's service regulations ordered that once a month at least the men must attend a confidential local party meeting; at these meetings they must not smoke nor leave the room like common mortals, and above all never take part in the discussion; for "the nobility keeps silence". The good material does not discuss, but only obeys and commands, "in responsibility upward, in command downward", as Hitler put it. The finest and most venomous flower of his contempt for humanity is the contempt of their own person that is expected of the good material: not only ruthless struggle to the death, but, in case of grave failure, suicide.

(9) Peter Padfield, Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991)

Himmler's goals were not confined to Bavaria. His aim was to unify the separate regional Political Police forces and so impose his system of "Political Police - concentration camps - SS" throughout the Reich. His eventual aim was to unify all police - "political", "criminal", "order", and the green Schutz-Polizei - and incorporate them into the SS as a national internal "protection" force. According to a high official in the SD, Dr Werner Best, this idea was fully developed in his mind by 1933. As already mentioned, Otto Strasser suggests that Himmler had prepared a memorandum on these lines for Hitler during his earliest days as Reichsfuhrer-SS.

He started to realise the idea that autumn, taking over, one by one, different Political Police forces. Precisely how it was done is not clear. It happened over some three months between October 1933 and January 1934, by which time he was Political Police Commander in every Land except Prussia. In several cases the way was opened by SS officers who had obtained leading positions in the police: Best for example was Police Commissioner in Hessen, SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Streckenbach chief of the newly formed Political Police in Hamburg. Elsewhere Heydrich's network of V-men could provide inside information for use in the manoeuvres for power. Himmler also had an ally in the Reich Interior Minister, Dr Frick, who had the similar goal of unifying all police forces of the Reich - under his own Ministry. He must also have had Hitler's ultimate backing, although no documentary evidence has surfaced to indicate a Fuhrer decree. Judging by events in Bavaria, he had the support of his "Duz-friend", Rohm too. This is understandable for Rohm needed friends himself at this time when SA excesses were conjuring powerful enemies. It is interesting that in September, just before Himmler began the series of police take-overs, Rohm issued an order valid for SA, SS and Stahlhelm - which he had incorporated into the SA - that in service matters the Reichsfuhrer-SS was to be addressed as "Mein Reichsfuhrer!"

In the separate negotiations with regional authorities leading up to his appointments, Himmler showed his political flair, using existing rivalries to further his suit, always prepared to make concessions to gain the main point in view. He and Heydrich were objects of deep unease throughout the Reich - the "black Diaskuren" (heavenly twins), as Diels referred to them, not simply on account of the black SS uniforms. On the other hand the reputation for efficiency of the "Political Police - concentration camp" system in Bavaria, and Dachau's notoriety, worked to Himmler's advantage; so did the success he had achieved in recruiting a high proportion of nobles and young lawyers into the SS, giving it a conventionally as well as racially elite status.

This other face of the SS, reassuringly reasonable, intelligent but realistic, socially ultra-acceptable, was epitomised by Himmler's new adjutant, Karl Wolff. Like Heydrich he conformed closely to the Aryan ideal, six feet tall, blond hair, blue eyes with a high enough forehead to give his face the required length. He was six months older than Himmler, and had the advantage of having served a year at the front where he had won promotion and the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd class for bravery and zeal. His father had been a director of the district court in Darmstadt, thus a member of the haute bourgeoisie, and Wolff had attended the most socially acceptable Gymnasium in the city. His war service had been with the exclusive Hessian Guard-Infantry regiment 115 led by the Grand Duke of Hessen-Darmstadt in person. Demobilised after the war, Wolff had taken a variety of bank and commercial jobs, married into a good family and gravitated to Munich as the nationalist mood boiled up just before Hitler's putsch. There in 1924, at a time when Himmler was despairing and unemployed, Wolff's agreeable personality had won him a post in a branch of a Hamburg advertising company and he performed so well that he was soon head of the branch. Within a year he had formed his own advertising firm, and it was only when this ran into trouble in the economic crises of 1931 that he had taken himself to the Brown House and signed an enrolment form for the SS: "I undertake to commit myself to the idea of Adolf Hitler, to maintain strictest Party discipline and to carry out the orders of the Reichsfuhrer of the Schutzstaffeln and the Party leadership conscientiously. I am German, of Aryan descent, belong to no freemasons' lodge and no secret society and promise to support the movement with all my powers."

The form passed up the chain of officials in the Reichsfuhrung, arriving on Himmler's desk some three weeks later, where the photograph attached was scrutinised through the pince-nez for non-Aryan blemishes in the features - Himmler claimed that all photographs were so examined - and sent out, approved, the same day.

Such was the man with the bearing of a soldier, the easy manners of an assured background, a naturally agreeable, persuasive personality - and with a National Socialist Weltanschauung soon grafted on to his nationalist outlook by the SS officer school - who, less than two years later, Himmler chose for his closest aide. It has been said that Himmler wanted to woo the Army at the time, and picked Wolff for the purpose, but Wolff was an asset in any company Himmler wished to impress, and did as well with the "Friends' Circle" of bankers and industrialists who donated to SS funds as with the officers of the Reichswehr or Land or Reich officials, or indeed SS or SA officers with proposals or quarrels. He was both reasonable persuader and emollient, and attempted to shield his chief as much as he could from the consequences of the immense responsibilities he was taking on. Heydrich was the fearful face of the Reichsfuhrer-SS, Wolff his "public relations" face. Himmler used both for his take-over of the regional Political Police. At the same time, by creating a rivalry between these two very different but most capable men, he sharpened their zeal and attachment to him, and safeguarded his own power position.

The picture of the unsoldierly, bespectacled Himmler, "to outward appearance a grotesque caricature of his own laws, norms and ideals", flanked by two such specimens of Aryan manhood and evidently compelling their devotion is something which has intrigued all commentators. And it was not only these two; there were a host of other blond, Nordic men from every background who looked up to him.

(10) Joachim Fest, The Face of the Third Reich (1963)