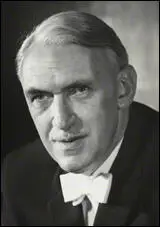

Alan Bullock

Alan Bullock, the son of Frank Bullock, was born in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, on 13th December, 1914. His father was a gardener and his mother, a maid. When he was a child his parents moved to Bradford where his father became a Unitarian minister and leader of the city's Literary Society. As one biographer pointed out: "The Bullocks were poor but high-minded, and spent what money they could on buying books and going to concerts. Father and son were close; by the time Alan was 16, they were talking together in Latin." He later argued that his father was "an autodidact of extraordinary mental power and spiritual feeling, who deeply affected all who knew him."

Bullock won a place at Bradford Grammar School. Another pupil at the school was Denis Healey: "Of all my contemporaries at Bradford, I most admired Alan Bullock... He was two years older than I, and won the Senior Essay Prize of the National Book Council in 1930, the same year as I won the Junior Essay Prize.... Alan had a range of knowledge and interests unique in our school; he seemed equally familiar with Wagner's letters and Joyce's Ulysses."

Bullock won a scholarship to Wadham College, where he studied for five years to win a rare double first in classics (1936) and modern history (1938). Soon after leaving Oxford University the outbreak of the Second World War took place. His asthma disqualified him from military service, and during the conflict he worked for the BBC Overseas Service.

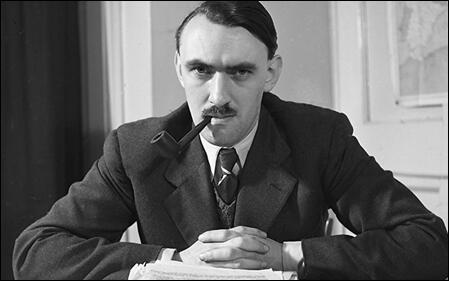

In 1945 he was appointed as a modern history fellow at New College. Over the next few years he worked on his first book, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1952). Mark Frankland has argued that the book on Adolf Hitler "remains both a standard work and an absorbing piece of modern historical writing. The book on which his reputation as a historian rests, it played to his strengths as a biographer who had the knack of penetrating the minds of others." This was followed by The Liberal Tradition from Fox to Keynes (1956) and a biography of Ernest Bevin, the trade union leader, The Life and Times of Ernest Bevin (1960).

In 1960 Bullock was appointed as founding master of St Catherine's College, the only new college for both undergraduates and graduates built in Oxford University in the 20th century. Mark Frankland claimed: "He was a powerfully built man, and some people found him domineering... He was Oxford's first full-time vice-chancellor (1969-73), serving during a difficult period of student unrest. His build, strong voice and irrepressible Yorkshire accent gave him an air of strength that was quite undonnish. This served him well when it came to keeping unruly undergraduates within limits." He was aware of this trait and once commented: "Bullock by name, and Bullock by nature."

Bullock was chairman of the Committee on Reading and Other Uses of English Language (1972-74) that resulted in the publication of the report A Language of Life (1975). The following year he chaired an investigation into industrial democracy (1976). He also served as chairman of the Tate Gallery (1973-1980).

Other books by Bullock include Faces of Europe (1980), The Humanist Tradition in the West (1985), Has History a Future? (1987), Hitler and Stalin: Parrallel Lives (1991) a biography of his father, Building Jerusalem (2000) and a single-volume biography of Ernest Bevin (2002).

Peter Dickson has argued: "Three intellectual characteristics are discernible. First is the apparently effortless ability to absorb huge amounts of information, whether from the unending Nuremberg documents, the trades-union or Foreign Office archives, or the enormous corpus of primary and secondary printed material on Stalinist Russia. Second is the ability to arrange this information objectively into convincing patterns, so that interpretation and judgement are always close behind description. Bullock wrote for truth, not for effect, and eschewed the heating up of controversy not unknown in other contemporary historians. Third, overlapping with this, are a breadth of historical perspective, and a force of imagination, which resulted from intuition as much as formal study."

Alan Bullock died on 2nd February, 2004.

Primary Sources

(1) Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (1989)

Of all my contemporaries at Bradford, I most admired Alan Bullock, who later wrote the biography of Ernest Bevin, became the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, and produced the Bullock Report on industrial democracy. He was two years older than I, and won the Senior Essay Prize of the National Book Council in 1930, the same year as I won the Junior Essay Prize. His father was a Unitarian minister and leader of the city's Literary Society. Alan had a range of knowledge and interests unique in our school; he seemed equally familiar with Wagner's letters and Joyce's Ulysses. He has remained a friend throughout the years, the breadth of his wisdom and humanity steadily growing with time.

(2) Mark Frankland, The Guardian (3rd February, 2004)

Bullock first caught the public's attention in 1952, with his biography Hitler, A Study In Tyranny, which, in its revised edition (1964), remains both a standard work and an absorbing piece of modern historical writing. The book on which his reputation as a historian rests, it played to his strengths as a biographer who had the knack of penetrating the minds of others....

Almost 40 years later, Bullock returned to the subject with his thousand-page tome Hitler And Stalin: Parallel Lives (1991, revised 1998). His definition of evil was "the corruption of people to behave in an inhuman way". His Hitler is ready to destroy anyone and anything in pursuit of abstract ideas. Stalin, Bullock argued, frightens us both because he justified his bloody methods as the only way to modernise a backward society and because of his extreme paranoia.

Friends warned Bullock against attempting this double biography, fearing it would flop. Some doubted the two lives were, in any meaningful sense, parallel; a handful felt Stalin was beyond the grasp of this very English Englishman. His colleague Norman Stone said Bullock's Stalin came out "like a Sheffield city councillor running amuck, and beheading the aldermen".

This was unfair, for Bullock had grasped that Stalin's personal malice marked him out from Hitler, who was astonishingly tolerant of inadequate colleagues. Asked the frivolous question as to which of the dictators he would have preferred spending a weekend with, Bullock replied promptly, "Hitler, because although it would have been boring in the extreme, you would have have had a greater certainty in coming back alive." The book was generally a critical success, and indisputably a commercial one, not least because of the clear English that was the hallmark of its writing.

Bullock began work on another book in the 1950s, a three-volume biography (1960, 1967 and 1983) of Ernest Bevin, the postwar Labour foreign secretary and a Bullock hero, whose character, in some respects, was remarkably like his own. He also made a stir as a teacher of history who seemed in touch with the outside world, and won a reputation in the lecture halls equal to that other Oxford star AJP Taylor. Bullock's lecture on Gladstone, delivered in a compulsive boom and packed with moral passion, is still remembered by those who heard it decades ago.

(3) Peter Dickson, The Independent (3rd February, 2004)

Review of Alan Bullock's work shows that he preferred to write books rather than articles, and operated on a large scale. Ernest Bevin: Foreign Secretary has nearly 900 pages, Parallel Lives in its revised version nearly 1,200.

Three intellectual characteristics are discernible. First is the apparently effortless ability to absorb huge amounts of information, whether from the unending Nuremberg documents, the trades-union or Foreign Office archives, or the enormous corpus of primary and secondary printed material on Stalinist Russia.

Second is the ability to arrange this information objectively into convincing patterns, so that interpretation and judgement are always close behind description. Bullock wrote for truth, not for effect, and eschewed the heating up of controversy not unknown in other contemporary historians. Third, overlapping with this, are a breadth of historical perspective, and a force of imagination, which resulted from intuition as much as formal study.

These are characteristics which Leopold von Ranke would have recognised. The older reader also gratefully acknowledges a lucidity and correctness of written English which Bullock's father would have much admired, and is not characteristic of our lax age.