Wilhelm Brückner

Wilhelm Brückner was born in Baden-Baden on 11th December 1884. He studied law and economics in Freiburg, Heidelberg and Munich. During the First World War he served in the Bavarian Army and reached the rank of lieutenant.

After the war, former senior officers in the German Army began raising private armies called Freikorps. Captain Kurt von Schleicher, of the political department at the army, secretly equipped and paid for the Freikorps. As Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "Composed of former officers, demobilized soldiers, military adventurers, fanatical nationalists, and unemployed youths, was organized by Captain Kurt von Schleicher. Rightist in political philosophy, blaming Social Democrats and Jews for Germany's plight, the Freikorps called for the elimination of traitors to the Fatherland."

Wilhelm Brückner held right-wing political views and joined the Freikorps and served under Colonel Franz Epp. One of the socialist leaders Eugen Levine, who was based in Munich, argued: "Colonel Epp is already recruiting volunteers. Students and other bourgeois youths are flocking to him from all sides. Nuremberg declared war on Munich. The gentlemen in Weimar recognise only Hoffmann's government. Noske is already whetting his butcher's knife, eager to rescue his threatened party friends and the threatened capitalists."

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner made a speech where he declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. Eisner explained that his program would be based on democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a republic.

On 9th November, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and the Chancellor, Max von Baden, handed power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy and was keen for one of the his grandsons to replace Wilhelm.

At the beginning of January, 1919, Chancellor Ebert ordered the removal of Emil Eichhorn, the head of the Police Department in Berlin. As Rosa Levine pointed out: "A member of the Independent Socialist Party and a close friend of the late August Bebel, he enjoyed great popularity among revolutionary workers of all shades for his personal integrity and genuine devotion to the working class. His position was regarded as a bulwark against counter-revolutionary conspiracy and was a thorn in the flesh of the reactionary forces."

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "The Berlin workers greeted the news that Eichhorn had been dismissed with a huge wave of anger. They felt he was being dismissed for siding with them against the attacks of right wing officers and employers. Eichhorn responded by refusing to vacate police headquarters. He insisted that he had been appointed by the Berlin working class and could only be removed by them. He would accept a decision of the Berlin Executive of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, but no other."

Members of the Independent Socialist Party and the German Communist Party jointly called for a protest demonstration. They were joined by members of the Social Democratic Party who were outraged by the decision of their government to remove a trusted socialist. Eichhorn remained at his post under the protection of armed workers who took up quarters in the building. A leaflet was distributed which spelt out what was at stake: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers. The blow which is aimed at the Berlin police chief will affect the whole German proletariat and the revolution."

Friedrich Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. Wilhelm Brückner served under Colonel Franz Epp in Berlin. By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck on 16th January. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were murdered while in police custody. The journalist, Morgan Philips Price, claimed that they were murdered by the Freikorps. It is estimated that Epp's men killed over 600 communists and socialists over the next few weeks.

In 1922 Brückner joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the following year was appointed leader of the Munich SA Regiment. With the help of Ernst Roehm, in February 1923, Adolf Hitler entered into negotiations with the Patriotic Leagues in Bavaria. This included the Lower Bavarian Fighting League, Reich Banner, Patriotic League of Munich and Oberland Defence League. A joint committee was set up under the chairmanship of Hermann Kriebel, the military leader of the Working Union of the Patriots Fighting Associations. Over the next few months Hitler and Roehm worked hard to bring in as many of the other right-wing groups as they could.

Gustav Stresemann, of the German National People's Party (DNVP), with the support of the Social Democratic Party, became chancellor of Germany in August 1923. On 26th September, he announced the decision of the government to call off the campaign of passive resistance in the Ruhr unconditionally, and two days later the ban on reparation deliveries to France and Belgium was lifted. He also tackled the problem of inflation by establishing the Rentenbank. Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has pointed out: "This was a courageous and wise decision, intended as the preliminary to negotiations for a peaceful settlement. But it was also the signal the Nationalists had been waiting for to stir up a renewed agitation against the Government."

With the help of Ernst Roehm, in February 1923, Adolf Hitler entered into negotiations with the Patriotic Leagues in Bavaria. This included the Lower Bavarian Fighting League, Reich Banner, Patriotic League of Munich and Oberland Defence League. A joint committee was set up under the chairmanship of Hermann Kriebel, the military leader of the Working Union of the Patriots Fighting Associations. Over the next few months Hitler and Roehm worked hard to bring in as many of the other right-wing groups as they could.

Gustav Stresemann, of the German National People's Party (DNVP), with the support of the Social Democratic Party, became chancellor of Germany in August 1923. On 26th September, he announced the decision of the government to call off the campaign of passive resistance in the Ruhr unconditionally, and two days later the ban on reparation deliveries to France and Belgium was lifted. He also tackled the problem of inflation by establishing the Rentenbank. Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has pointed out: "This was a courageous and wise decision, intended as the preliminary to negotiations for a peaceful settlement. But it was also the signal the Nationalists had been waiting for to stir up a renewed agitation against the Government."

Hermann Kriebel, Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goering and Ernst Roehm had a meeting together on 25th September where they discussed what they were to do. Hitler told the men that it was time to take action. Roehm agreed and resigned his commission to give his full support to the cause. Hitler's first step was to put his own 15,000 Sturm Abteilung men in a state of readiness. The following day, the Bavarian Cabinet proclaimed a state of emergency and appointed Gustav von Kahr, one of the best-known politicians, with strong right-wing leanings, as State Commissioner with dictatorial powers. Kahr's first act was to ban Hitler from holding meetings.

General Hans von Seeckt made it clear that he would take action if Hitler attempted to take power. As William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964), has pointed out: "He issued a plain warning to... Hitler and the armed leagues that any rebellion on their part would be opposed by force. But for the Nazi leader it was too late to draw back. His rabid followers were demanding action." Wilhelm Brückner urged him to strike at once: "The day is coming, when I won't be able to hold the men back. If nothing happens now, they'll run away from us."

A plan of action was suggested by Alfred Rosenberg and Max Scheubner-Richter. The two men proposed to Hitler that they should strike on 4th November during a military parade in the heart of Munich. The idea was that a few hundred storm troopers should converge on the street before the parading troops arrived and seal it off with machine-guns. However, when the SA arrived they discovered the street was fully protected by a large body of well-armed police and the plan had to be abandoned. It was then decided that the putsch should take place three days later.

On 8th November, 1923, the Bavarian government held a meeting of about 3,000 officials. While Gustav von Kahr, the prime minister of Bavaria was making a speech, Adolf Hitler and 600 armed SA men entered the building. According to Ernst Hanfstaengel: "Hitler began to plough his way towards the platform and the rest of us surged forward behind him. Tables overturned with their jugs of beer. On the way we passed a major named Mucksel, one of the heads of the intelligence section at Army headquarters, who started to draw his pistol as soon as he saw Hitler approach, but the bodyguard had covered him with theirs and there was no shooting. Hitler clambered on a chair and fired a round at the ceiling." Hitler then told the audience: "The national revolution has broken out! The hall is filled with 600 armed men. No one is allowed to leave. The Bavarian government and the government at Berlin are hereby deposed. A new government will be formed at once. The barracks of the Reichswehr and the police barracks are occupied. Both have rallied to the swastika!"

Leaving Hermann Goering and the SA to guard the 3,000 officials, Hitler took Gustav von Kahr, Otto von Lossow, the commander of the Bavarian Army and Hans von Seisser, the commandant of the Bavarian State Police into an adjoining room. Hitler told the men that he was to be the new leader of Germany and offered them posts in his new government. Aware that this would be an act of high treason, the three men were initially reluctant to agree to this offer. Adolf Hitler was furious and threatened to shoot them and then commit suicide: "I have three bullets for you, gentlemen, and one for me!" After this the three men agreed.

Soon afterwards Eric Ludendorff arrived. Ludendorff had been leader of the German Army at the end of the First World War. He had therefore found Hitler's claim that the war had not been lost by the army but by Jews, Socialists, Communists and the German government, attractive, and was a strong supporter of the Nazi Party. Ludendorff agreed to become head of the the German Army in Hitler's government.

While Adolf Hitler had been appointing government ministers, Ernst Roehm, leading a group of storm troopers, had seized the War Ministry and Rudolf Hess was arranging the arrest of Jews and left-wing political leaders in Bavaria. Hitler now planned to march on Berlin and remove the national government. Surprisingly, Hitler had not arranged for the Sturm Abteilung (SA) to take control of the radio stations and the telegraph offices. This meant that the national government in Berlin soon heard about Hitler's putsch and gave orders to General Hans von Seeckt for it to be crushed.

Gustav von Kahr, Otto von Lossow and Hans von Seisser, managed to escape and Von Kahr issued a proclamation: "The deception and perfidy of ambitious comrades have converted a demonstration in the interests of national reawakening into a scene of disgusting violence. The declarations extorted from myself, General von Lossow and Colonel Seisser at the point of the revolver are null and void. The National Socialist German Workers' Party, as well as the fighting leagues Oberland and Reichskriegsflagge, are dissolved."

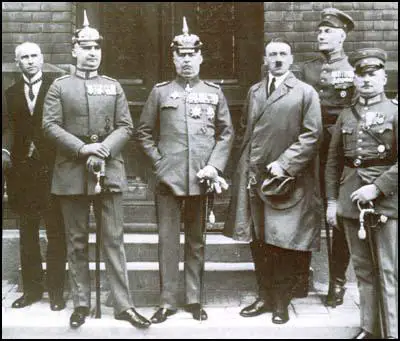

Hermann Kriebel and Ernst Roehm on 8th November 1923

The next day Wilhelm Brückner, Hermann Kriebel, Adolf Hitler, Eric Ludendorff, Julius Steicher, Hermann Goering, Max Scheubner-Richter and 3,000 armed supporters of the Nazi Party marched through Munich in an attempt to join up with Roehm's forces at the War Ministry. At Odensplatz they found the road blocked by the Munich police. What happened next is in dispute. One observer said that Hitler fired the first shot with his revolver. Another witness said it was Steicher while others claimed the police fired into the ground in front of the marchers.

William L. Shirer has argued: "At any rate a shot was fired and in the next instant a volley of shots rang out from both sides, spelling in that instant the doom of Hitler's hopes. Scheubner-Richter fell, mortally wounded. Goering went down with a serious wound in his thigh. Within sixty seconds the firing stopped, but the street was already littered with fallen bodies - sixteen Nazis and three police dead or dying, many more wounded and the rest, including Hitler, clutching the pavement to save their lives." Louis L. Snyder later commented: "In seconds 16 Nazis and 3 policeman lay dead on the pavement, and others were wounded. Goering, who was shot through the thigh, fell to the ground. Hitler, reacting spontaneously because of his training as a dispatch bearer during World War I, automatically hit the pavement when he heard the crack of guns. Surrounded by comrades, he escaped in a car standing close by. Ludendorff, staring straight ahead, moved through the ranks of the police, who in a gesture of respect for the old war hero, turned their guns aside."

Hitler, who had dislocated his shoulder, lost his nerve and ran to a nearby car. Although the police were outnumbered, the Nazis followed their leader's example and ran away. Only Eric Ludendorff and his adjutant continued walking towards the police. Later Nazi historians were to claim that the reason Hitler left the scene so quickly was because he had to rush an injured young boy to the local hospital.

At his trial Adolf Hitler was allowed to turn the proceedings into a political rally. "The army we have trained is growing from day to day, from hour to hour. At this very time I hold to the proud hope that the hour will come when these wild bands will be formed into battalions, the battalions into regiments, the regiments into divisions.... Then from our bones and our graves will speak the voice of that court which alone is empowered to sit in judgment on us all. For not you, gentlemen, will deliver judgment on us; that judgment will be pronounced by the eternal court of history, which will arbitrate the charge that has been made against us.... That court will judge us, will judge the Quartermaster General of the former army, will judge his officers and soldiers as Germans who wanted the best for their people and their Fatherland, who were willing to fight and die."

After the failed coup Ernst Hanfstaengel hid Adolf Hitler in his villa in the Bavarian Alps for several days, Hitler was arrested and put on trial for treason. If found guilty, Hitler faced the death penalty. Also tried for this offence was Wilhelm Brückner, Eric Ludendorff, Wilhelm Frick, Hermann Kriebel, Ernst Roehm, Friedrich Weber and Ernst Pohner. It soon became clear that the Bavarian authorities were unwilling to punish the men too severely.

The State Prosecutor, Ludwig Stenglein, was remarkably tolerant towards Hitler in court: "His (Hitler) honest endeavour to reawaken the belief in the German cause among an oppressed and disarmed people.... His private life has always been clean, which deserves special approbation in view of the temptations which naturally came to him as an acclaimed party leader.... Hitler is a highly gifted man who, coming from a simple background, has, through serious and hard work, won for himself a respected place in public life. He dedicated himself to the ideas that inspired him to the point of self-sacrifice, and as a soldier he fulfilled his duty in the highest measure."

At his trial Adolf Hitler was allowed to turn the proceedings into a political rally. "The army we have trained is growing from day to day, from hour to hour. At this very time I hold to the proud hope that the hour will come when these wild bands will be formed into battalions, the battalions into regiments, the regiments into divisions.... Then from our bones and our graves will speak the voice of that court which alone is empowered to sit in judgment on us all. For not you, gentlemen, will deliver judgment on us; that judgment will be pronounced by the eternal court of history, which will arbitrate the charge that has been made against us.... That court will judge us, will judge the Quartermaster General of the former army, will judge his officers and soldiers as Germans who wanted the best for their people and their Fatherland, who were willing to fight and die."

Hitler was found guilty he only received the minimum sentence of five years. Ludendorff was acquitted and the others, although found guilty, only received very light sentences. Brückner was sent to Landsberg Castle in Munich to serve his prison sentence with Hitler, Emil Maurice, Rudolf Hess and Hermann Kriebel.

and Wilhelm Brückner at Landsberg.

Brückner was released only four and a half months of his prison sentence. He returned to his role as commander of the later and once again took over his old SA regiment's leadership. In 1930 he became Hitler's adjutant and bodyguard. Brückner joined Hitler inner-circle that included Ernst Roehm, Gregor Strasser, Herman Goering , Joseph Goebbels, Baldur von Schirach, Rudolf Hess, Max Amann, Franz Schwarz and Hans Frank.

On 9th November 1934, Brückner was appointed SA Obergruppenführer by Hitler. He later recommended his personal doctor, Karl Brandt, to Hitler. After a disagreement with Martin Bormann he was sacked by Hitler in October 1940 and replaced by Julius Schaub as his chief adjutant. He joined the German Army and by the end of the war held the rank of colonel.

Wilhelm Brückner died in Chiemgau on 18th August 1954.

Primary Sources

(1) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964)

At any rate a shot was fired and in the next instant a volley of shots rang out from both sides, spelling in that instant the doom of Hitler's hopes. Scheubner-Richter fell, mortally wounded. Goering went down with a serious wound in his thigh. Within sixty seconds the firing stopped, but the street was already littered with fallen bodies - sixteen Nazis and three police dead or dying, many more wounded and the rest, including Hitler, clutching the pavement to save their lives.

There was one exception, and had his example been followed, the day might have had a different ending. Ludendorff did not fling himself to the ground. Standing erect and proud in the best soldierly tradition, with his adjutant, Major Streck, at his side, he marched calmly on between the muzzles of the police rifles until he reached the Odeonsplatz. He must have seemed a lonely and bizarre figure. Not one Nazi followed him. Not even the supreme leader, Adolf Hitler.

The future Chancellor of the Third Reich was the first to scamper to safety. He had locked his left arm with the right arm of Scheubner-Richter (a curious but perhaps revealing gesture) as the column approached the police cordon, and when the latter fell he pulled Hitler down to the pavement with him. Perhaps Hitler thought he had been wounded; he suffered sharp pains which, it was found later, came from a dislocated shoulder. But the fact remains that according to the testimony of one of his own Nazi followers in the column, the physician Dr Walther Schulz which was supported by several other witnesses, Hitler "was the first to get up and turn back", leaving his dead and wounded comrades lying in the street. He was hustled into a waiting motor car and spirited off to the country home of the Hanfstaengls at Uffing, where Putzi's wife and sister nursed him and where, two days later, he was arrested.

Ludendorff was arrested on the spot. He was contemptuous of the rebels who had not had the courage to march on with him, and so bitter against the Army for not coming over to his side that he declared henceforth he would not recognize a German officer nor ever again wear an officer's uniform. The wounded Goering was given first aid by the Jewish proprietor of a nearby bank into which he had been carried and then smuggled across the frontier into Austria by his wife and taken to a hospital in Innsbruck. Hess also fled to Austria. Roehm surrendered at the War Ministry two hours after the collapse before the Feldherrnhalle. Within a few days all the rebel leaders except Goering and Hess were rounded up and jailed.