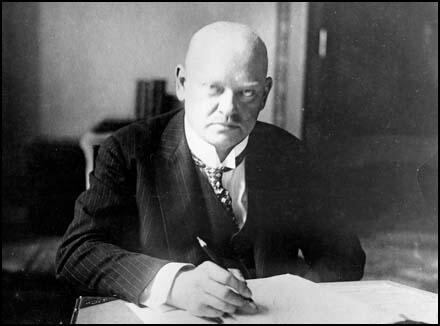

Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Stresemann, the son of a innkeeper, was born in Berlin on 10th May, 1878. Stresemann attended universities in Berlin and Leipzig where he studied history, literature and economics.

After completing his studies he worked for the German Chocolate Makers's Association. In 1902 he founded the Saxon Manufacturers' Association and the following year joined the National Liberal Party. A right-wing party, Stresemann emerged as one of the leaders of the more moderate wing who favoured an improvement in social welfare provision.

In 1908 Stresemann was elected to the Reichstag. He soon came into conflict with his more conservative colleagues and he was ousted from the party's executive committee in 1912. Later that year he lost his seat in Parliament. Stresemann returned to business life and was the founder of the German-American Economic Association. A strong advocate of German imperialism, he aliened himself with the political views of Alfred von Tirpitz and Bernhard von Bulow.

He returned to the Reichstag in 1914. Exempted from military service during the First World War because of poor health, Stresemann was a passionate supporter of the war effort and advocated that Germany should take possession of land in Russia, Poland, France and Belgium.

During the war Stresemann became increasing right-wing in his views and his opponents claimed he was the parliamentary spokesman for military figures such as Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. He became increasingly critical of Bethmann Hollweg and advocated unrestricted submarine warfare against the Royal Navy.

In 1918 Stresemann formed the German People's Party. After Germany's defeat Stresemann was sympathetic to the Freikorps and welcomed the defeat of the socialists and communists in the German Revolution. However, he became increasingly concerned by the use of violence of the right-wing groups and after the murders of Matthias Erzberger and Walther Rathenau, Stresemann decided to argue in favour of the Weimar Republic.

With the support of the Social Democratic Party Stresemann became chancellor of Germany in 1923. He managed to bring an end to the passive resistance in the Ruhr and resumed payment of reparations. He also tackled the problem of inflation by establishing the Rentenbank.

Stresemann was severely criticized by members of the Social Democratic Party and Communist Party over his unwillingness to deal firmly with Adolf Hitler and other Nazi Party leaders after the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch. Later that month the socialists withdrew from Stresemann's government and he was forced to resign as chancellor.

In the new government led by Wilhelm Marx, Stresemann was appointed as foreign minister. He accepted the Dawes Plan (1924) as it resulted in the French Army withdrawing from the Ruhr. Under Hans Luther Stresemann's skilled statesmanship led to the Locarno Treaty (December, 1925), the German-Soviet Treaty (April, 1926) and Germany joining the League of Nations in 1926. Later that year he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Gustav Stresemann negotiated the Young Plan but soon after that he suffered two strokes and on 3rd October, 1929 he died of a heart attack.

Primary Sources

(1) Gustav Stresemann, Friedrich Ebert (1925)

I have spoken before of the loss we have sustained in losing a man who might well have been the instrument of a great work of reconciliation in Germany. To me his loss seems the heaviest because such reconciliation is so sorely needed. The old Germany and the new ought not to be permanently opposed; the Reichsbanner and the Stahlhelm should not for ever face each other as antagonists. Some means must be found of fusing the old and the new. And the dead man would certainly have been one of those who would have set themselves wholeheartedly to such a task. The reserve with which we formerly regarded the President, which had indeed already been broken through by the impression of his conscientious labours, vanished on that August 11th when the President made up his mind to raise the Deutschlandlied above the turmoil of Party strife and restore it to its place as the song of the Germans. Let us not underestimate such a symbol. We wave flags enough against each other. It would be a pity if we tried to sing each other down! Thus we have at least a national song that unites all Germans, and is the symbol of our sixty-million nation.

(2) Gustav Stresemann, diary entry (28th April, 1925)

The result of the election is psychologically extraordinarily interesting. There can be no doubt that the personal element won the day. During the turmoil of the election campaign there was no lack of effort to discredit the significance of Hindenburg's personality. But with little success. Many indeed were doubtful whether the burden of age might not be too heavy for one who aspired to the Presidential office. But in the end the great name produced its effect, and brought forth reserves of voters who would hardly otherwise have been available in such numbers if they had not regarded it as a patriotic duty to record their votes for the great commander in the Great War.

On the other side, Hindenburg's nomination combined the Weimar Coalition even more firmly than would have otherwise been the case. Anyone acquainted with the reports of the meetings held by the Social Democratic Party at the time of the elections knows how violent was the reaction against the idea of electing a leading member of the Centre Party to the Presidency. It was opposed by the Levi Group, which saw a betrayal of the conception of the Class War in any co-operation with the Centre bourgeoisie. It was opposed by the whole body of Freethinkers - and where are these stronger than in the ranks of the Social Democratic Party? - who had no notion of voting for the champion of denominational schools, and the avowed supporter of the Christian attitude to the State and the world. It was opposed above all by the women in the areas where the denominational conflict is acute, owing to their fear that the election of Marx would lead to a strengthening of Catholicism. And the opposition was much more intense among the Democrats. Not only from Bavaria came protests against the support of the Centre candidate. In other districts too the Democratic creed was shaken.

(3) Gustav Stresemann, diary entry (19th July, 1925)

Peace between France and Germany is not merely a Franco-German but a European affair. The last world War in my opinion produced no victors who could rejoice in their victory. The War, and the continuation of the War by other means, were responsible for social, political, and economic upheavals in Europe which have directly confronted the older civilized nations with the question of their future material existence. In the debates that recently took place in this honourable House, you have discussed a problem that is one of the effects of the War on Europe, not merely on Germany, namely the problem how to relieve by any public measures those who have been proletarianized by the collapse of currency and trade. They were, not merely in this country but in others, the supporters of the idea of the State, the most steadfast pillars of the present order. The collapse of the currency has spread from East to West, and has hitherto not stopped at any national frontier. I do not belong to those who expect any advantages for Germany from the continuance of this currency fall in France. I can envisage no political or even economic advantages if this fall goes on. Still less do I share the opinion which seemed to be implicit in an interjection at the beginning of my remarks, to the effect that the position of France as a Great Power, which she held after the Peace of Versailles, can be permanently shaken by any difficulties in the Rif territories of Morocco.

Not here lie the great problems of the present time; they lie, I believe, in the fact that, without the cooperation of the great territories that are today the paramount factors in the trade of the world, neither French financial distress nor German economic distress can be removed. It is not merely our interest but that of other nations in Europe that these world Powers should set about the reconstruction of a ruined Europe, and they cannot expect these world Powers and their public opinion to undertake the task, unless they~feel that they have before them a pacified Europe, and not a Europe of sanctions and of wars yet to come.

(4) Gustav Stresemann, speech after the signing of the Locarno Treaty (16th October, 1925)

At the moment of initialling the treaties that have here been drafted will you allow me to say a few words in the name of the Chancellor and in my own. The German delegates agree to the text of the final protocol and its annexes, an agreement to which we have given expression by adding our initials. Joyfully and wholeheartedly we welcome the great development in the European concept of peace that has its origin in this meeting at Locarno, and as the Treaty of Locarno, is destined to be a landmark in the history of the relations of States and peoples to each other. We especially welcome the expressed conviction set forth m this final protocol that our labours will lead to decreased tension among the peoples and to an easier solution of so many political and economic problems.

We have undertaken the responsibility of initialling the treaties because we live in the faith that only by peaceful cooperation of States and peoples can that development be secured, which is nowhere more important than for that great civilized land of Europe whose peoples have suffered so bitterly in the years that lie behind us. We have more especially undertaken it because we are justified in the confidence that the political effects of the treaties will prove to our particular advantage in relieving the conditions of our political life. But great as is the importance of the agreements that

are here embodied, the treaties of Locarno will only achieve their profoundest importance in the development of the nations if Locarno is not to be the end but the beginning of confident cooperation among the nations. That these prospects, and the hopes based upon our work, may come to fruition is the earnest wish to which the German delegates would give expression at this solemn moment.

(5) Gustav Stresemann, speech on the Locarno Treaty (December, 1925)

At the moment when the work begun at Locarno is concluded by our signature in London, I should like to express above all to you, Sir Austen Chamberlain, our gratitude for what we owe you in the recognition of your leadership in the work that is completed here today. We had, as you know, no chairman to preside over our negotiations at Locarno. But it is due to the great traditions of your country, which can look back to an experience of many hundred years, that unwritten laws work far better than the form in which man thinks to master events. Thus, the Conference of Locarno, which was so informal, led to a success. That was possible because in you, Sir Austen Chamberlain, we had a leader who by his tact and friendliness, supported by his charming wife, created that atmosphere of personal confidence that may well be regarded as a part of what is meant by the spirit of Locarno. But something else was more important than personal approach, and that was the will, so vigorous in yourself and in us, to bring this work to a conclusion. Hence the joy that you felt like the rest of us, when we came to initial those documents at Locarno. And hence our sincere gratitude to you here today.

In speaking of the work done at Locarno, let me look at it in the light of this idea of form and will. We have all had to face debates on this achievement in our respective Houses of Parliament Light has been thrown upon it in all directions, and attempts have been made to discover whether there may not be contradictions in this or that clause. In this connection I say one word! I see in Locarno not a juridical structure of political ideas, but the basis of great developments in the future. Statesmen and nations therein proclaim their purpose to prepare the way for the yearnings of humanity after peace and understanding. If the pact were no more than a collection of clauses, it would not hold. The form that it seeks to find for the common life of nations will only become a reality if behind them stands the will to create new conditions in Europe, a will that inspired the words that Herr Briand has just uttered. '

I should like to express to you, Herr Briand, my deep gratitude for what you said about the necessity of the cooperation of all peoples - and especially of those peoples that have endured so much in the past. You started from the idea that every one of us belongs in the first instance to his own country, and should be a good Frenchman, German, Englishman, as being a part of his own people, but that everyone also is a citizen of Europe, pledged to the great cultural idea that finds expression in the concept of our continent. We have a right to speak of a European idea; this Europe of ours has made such vast sacrifices in the Great War, and yet it is faced with the danger of losing, through the effects of that Great

War, the position to which it is entitled by tradition and development.

The sacrifices made by our continent in the World War are often measured solely by the material losses and destruction that resulted from the War. Our greatest loss is that a generation has perished from which we cannot tell how much intellect, genius, force of act and will, might have come to maturity, if it had been given to them to live out their lives. But together with the convulsions of the World War one fact has emerged, namely that we are bound to one another by a single and a common fate. If we go down, we go down together; if we are to reach the heights, we do so not by conflict but by common effort.

For this reason, if we believe at all in the future of our peoples, we ought not to live in disunion and enmity, we must join hands in common labour. Only thus will it be possible to lay the foundations for a future of which you, Herr Briand, spoke in words that I can only emphasize, that it must be based on a rivalry of spiritual achievement, not of force. In such co-operation the basis of the future must be sought. The great majority of the German people stands firm for such a peace as this. Relying on this will to peace, we set our signature to this treaty. It is to introduce a new era of cooperation among the nations. It is to close the seven years that followed the War, by a time of real peace, upheld by the will of responsible and far-seeing statesmen, who have shown us the way to such development, and will be supported by their peoples, who know that only in this fashion can prosperity increase. May later generations have cause to bless this day as the beginning of a new era.