German Revolution

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a ceasefire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (1)

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace." (2)

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Keil soon travelled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power." (3)

November Uprising in Bavaria

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks." (4)

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Several leading socialists arrived in the city to support the new regime. This included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution. (5)

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds." (6)

Eisner made a speech pointing out the connections between art and revolution: "A politician who is not an artist is also no politician. It is a delusion of our unpolitical German people to believe you can achieve something in the world without such poetic power. The poet is no unpractical dreamer: he is the prophet of the future… Art should no longer be a refuge for those who despair of life, for life itself should be a work of art, and the state the greatest work of art." (6a)

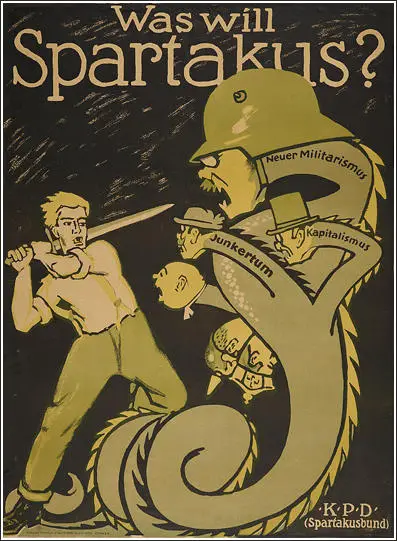

The Spartacus League

Chancellor, Max von Baden, decided to hand over power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy: "You have no right to proclaim the republic." (7)

Karl Liebknecht climbed to a balcony in the Imperial Palace and made a speech: "The day of Liberty has dawned. I proclaim the free socialist republic of all Germans. We extend our hand to them and ask them to complete the world revolution. Those of you who want the world revolution, raise your hands." It is claimed that thousands of hands rose up in support of Liebknecht. (8)

The Social Democratic Party press, fearing the opposition of the left-wing Spartacus League, proudly trumpeted their achievements: "The revolution has been brilliantly carried through... the solidarity of proletarian action has smashed all opposition. Total victory all along the line. A victory made possible because of the unity and determination of all who wear the workers' shirt." (9)

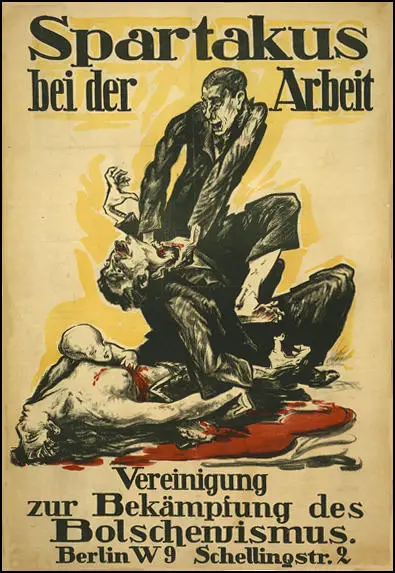

Ebert gave permission for the publishing of a Social Democratic Party leaflet that attacked the activities of the Spartacus League, led by Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches and Clara Zetkin: "The shameless doings of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg besmirch the revolution and endanger all its achievements. The masses cannot afford to wait a minute longer and quietly look on while these brutes and their hangers-on cripple the activity of the republican authorities, incite the people deeper and deeper into a civil war, and strangle the right of free speech with their dirty hands. With lies, slander, and violence they want to tear down everything that dares to stand in their way. With an insolence exceeding all bounds they act as though they were masters of Berlin."(10)

Heinrich Ströbel, a journalist based in Berlin believed that some leaders of the Spartacus League overestimated their support: "The Spartakist movement, which also influenced a section of the Independents, succeeded in attracting a fraction of the workers and soldiers and keeping them in a state of constant excitement, but it remained without a hold on the great mass of the German proletariat. The daily meetings, processions, and demonstrations which Berlin witnessed... deceived the public and the Spartakist leaders into believing in a following for this revolutionary section which did not exist." (11)

Council of the People's Deputies

Friedrich Ebert established the Council of the People's Deputies, a provisional government consisting of three delegates from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and three from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Liebknecht was offered a place in the government but he refused, claiming that he would be a prisoner of the non-revolutionary majority. A few days later Ebert announced elections for a Constituent Assembly to take place on 19th January, 1918. Under the new constitution all men and women over the age of 20 had the vote. (12)

As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League." (13)

Luxemburg was aware that the Spartacus League only had 3,000 members and not in a position to start a successful revolution. The Spartacus League consisted chiefly of innumerable small and autonomous groups scattered all over the country. John Peter Nettl has argued that "organisationally Spartakus was slow to develop... In the most important cities it evolved an organised centre only in the course of December... and attempts to arrange caucus meetings of Spartakist sympathisers within the Berlin Workers' and Soldiers' Council did not produce satisfactory results." (14)

Pierre Broué suggests that the large meetings helped to convince Karl Liebknecht that a successful revolution was possible. "Liebknecht, an untiring agitator, spoke everywhere where revolutionary ideas could find an echo... These demonstrations, which the Spartakists had neither the force nor the desire to control, were often the occasion for violent, useless or even harmful incidents caused by the doubtful elements who became involved in them... Liebknecht could have the impression that he was master of the streets because of the crowds which acclaimed him, while without an authenic organisation he was not even the master of his own troops." (15)

On 1st January, 1919, there was a convention of the Spartacus League. Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Levi and Leo Jogiches all recognised that a "successful revolution depended on more than temporary support for certain slogans by a disorganised mass of workers and soldiers". (16) They were outvoted on this issue. As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "In vain did she (Luxemburg) try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising." (17)

German Revolution in Berlin

Emil Eichhorn had been appointed head of the Police Department in Berlin. As Rosa Levine pointed out: "A member of the Independent Socialist Party and a close friend of the late August Bebel, he enjoyed great popularity among revolutionary workers of all shades for his personal integrity and genuine devotion to the working class. His position was regarded as a bulwark against counter-revolutionary conspiracy and was a thorn in the flesh of the reactionary forces." (18)

On 4th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert, ordered the removal of Emil Eichhorn, as head of the Police Department. Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "The Berlin workers greeted the news that Eichhorn had been dismissed with a huge wave of anger. They felt he was being dismissed for siding with them against the attacks of right wing officers and employers. Eichhorn responded by refusing to vacate police headquarters. He insisted that he had been appointed by the Berlin working class and could only be removed by them. He would accept a decision of the Berlin Executive of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, but no other." (19)

The Spartacus League published a leaflet that claimed: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers." It is estimated that over 100,000 workers demonstrated against the sacking of Eichhorn the following Sunday in "order to show that the spirit of November is not yet beaten." (20)

Paul Levi later reported that even with this provacation, the Spartacus League leadership still believed they should resist an open rebellion: "The members of the leadership were unanimous; a government of the proletariat would not last more than a fortnight... It was necessary to avoid all slogans that might lead to the overthrow of the government at this point. Our slogan had to be precise in the following sense: lifting of the dismissal of Eichhorn, disarming of the counter-revolutionary troops, arming of the proletariat." (21)

Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck published a leaflet calling for a revolution. "The Ebert-Scheidemann government has become intolerable. The undersigned revolutionary committee, representing the revolutionary workers and soldiers, proclaims its removal. The undersigned revolutionary committee assumes provisionally the functions of government." Karl Radek, had been sent by Lenin, to encourage a revolution, later commented that Rosa Luxemburg was furious with Liebknecht and Pieck for getting carried away with the idea of establishing a revolutionary government." (22)

Although massive demonstrations took place, no attempt was made to capture important buildings. On 7th January, Luxemburg wrote in the Die Rote Fahne: "Anyone who witnessed yesterday's mass demonstration in the Siegesalle, who felt the magnificent mood, the energy that the masses exude, must conclude that politically the proletariat has grown enormously through the experiences of recent weeks.... However, are their leaders, the executive organs of their will, well informed? Has their capacity for action kept pace with the growing energy of the masses?" (23)

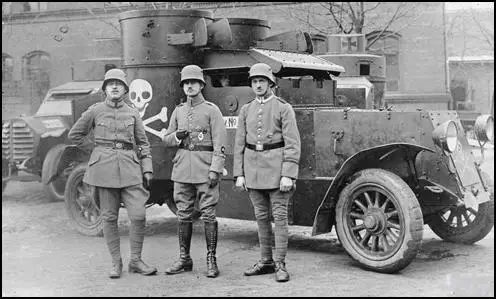

General Kurt von Schleicher, was on the staff of Paul von Hindenburg. In December 1919 he helped organize the Freikorps, in an attempt to prevent a German Revolution. The group was composed of "former officers, demobilized soldiers, military adventurers, fanatical nationalists and unemployed youths". Holding extreme right-wing views, von Schleicher blamed left-wing political groups and Jews for Germany's problems and called for the elimination of "traitors to the Fatherland". (24)

The Freikorps appealed to thousands of officers who identified with the upper class and had nothing to gain from the revolution. There were also a number of privileged and highly trained troops, known as stormtroopers, who had not suffered from the same rigours of discipline, hardship and bad food as the mass of the army: "They were bound together by an array of privileges on the one hand, and a fighting camaraderie on the other. They stood to lose all this if demobilised - and leapt at the chance to gain a living by fighting the reds." (25)

Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, was also in contact with General Wilhelm Groener, who as First Quartermaster General, had played an important role in the retreat and demobilization of the German armies. According to William L. Shirer, the SDP leader and the "second-in-command of the German Army made a pact which, though it would not be publicly known for many years, was to determine the nation's fate. Ebert agreed to put down anarchy and Bolshevism and maintain the Army in all its tradition. Groener thereupon pledged the support of the Army in helping the new government establish itself and carry out its aims." (26)

On the 5th January, Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. Groener later testified that his aim in reaching accommodation with Ebert was to "win a share of power in the new state for the army and the officer corps... to preserve the best and strongest elements of old Prussia". Ebert was motivated by his fear of the Spartacus League and was willing to use "the armed power of the far-right to impose the government's will upon recalcitrant workers, irrespective of the long-term effects of such a policy on the stability of parliamentary democracy". (27)

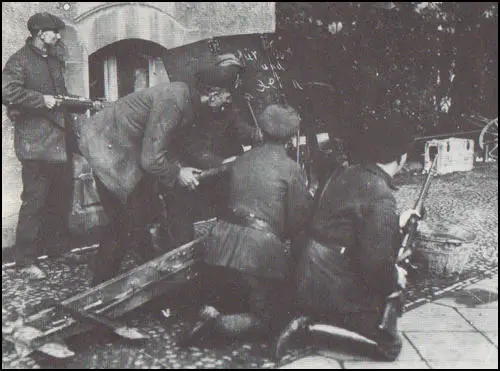

rolls of newsprint as barricades (January, 1919)

The soldiers who entered Berlin were armed with machine-guns and armoured cars and demonstrators were killed in their hundreds. Artillery was used to blow the front off the police headquarters before Eichhorn's men abandoned resistance. "Little quarter was given to its defenders, who were shot down where they were found. Only a few managed to escape across the roofs." (28)

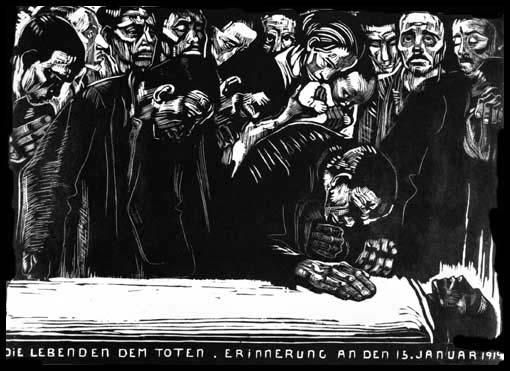

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal." (29) Vorwärts, the newspaper owned by the German Social Democrat Party reported the following day: Vorwärts has the honour of announcing in advance of all other papers that Karl Liebknecht had been "shot while trying to escape" and Rosa Luxemburg was "killed by the people". (30)

Paul Frölich blamed the Berlin newspapers for building up a hatred of the Socialist League: "The armed mercenaries of the counter-revolution were savagely slaughtering their prisoners and the press sang hymns in praise of the deliverers. It described with gusto the blood and brain splattered walls against which batches of workers were being mown down. The unscrupulous campaign of the press turned the middle and lower middle class into a bloodthirsty mob eager to drive men and women before the rifles of the execution squads on the slightest suspicion." (31)

On the morning of the funeral Kollwitz visited the Liebknecht home to offer sympathy to the family. At their request, she made drawings of him in his coffin. She noted that there were red flowers around his forehead, where he had been shot. She wrote in her journal: "I am trying the Liebknecht drawing as a lithograph... Lithography now seems to be the only technique I can still manage. It's hardly a technique at all, its so simple. In it only the essentials count." However, she changed her mind and it became a woodcut. (31a)

The Karl Liebknecht woodcut was attacked by the German Communist Party (KPD) because it had not been produced by a member of the party. Kollwitz wrote in her journal: "As an artist who moreover is a woman cannot be expected to unravel these crazily complicated relationships. As an artist I have the right to extract the emotional content out of everything, to let things work upon me and then give them outward form. And so I also have the right to portray the working class's farewell to Liebknecht, and even dedicate it to the workers, without following Liebknecht politically." (31b)

The elections for the National Assembly took place on 19th January 1919. The turnout rate was 83%. Over 90% of the women eligible voted. The result was as follows: German Social Democrat Party (38.72%), Independent Social Democratic Party (5.23%), German Democratic Party (21.62%), German National People's Party (17.81%) and German People's Party (4.51).

Bavarian Soviet Republic

In Bavaia, Kurt Eisner formed a coalition with the German Social Democrat Party (SDP) in the National Assembly. The Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) only receied 2.5% of the total vote and he decided to resign to allow the SDP to form a stable government. He was on his way to present his resignation to the Bavarian parliament on 21st February, 1919, when he was assassinated in Munich by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. (32)

It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." Johannes Hoffmann, of the SDP, replaced Eisner as President of Bavaria. One armed worker walked into the assembled parliament and shot dead one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Party. Many of the deputies fled in terror from the city. (33)

Max Levien, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), became the new leader of the revolution. Rosa Levine-Meyer argued: "Levien.... was a man of great intelligence and erudition and an excellent speaker. He exercised an enormous appeal of the masses and could, with no great exaggeration, be defined as the revolutionary idol of Munich. But he owed his popularity rather to his brilliance and wit than to clear-mindedness and revolutionary expediency." (34)

On 7th April, 1919, Levien declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. A fellow revolutionary, Paul Frölich later commented: "The Soviet Republic did not arise from the immediate needs of the working class... The establishment of a Soviet Republic was to the Independents and anarchists a reshuffling of political offices... For this handful of people the Soviet Republic was established when their bargaining at the green table had been closed... The masses outside were to them little more than believers about to receive the gift of salvation from the hands of these little gods. The thought that the Soviet Republic could only arise out of the mass movement was far removed from them. While they achieved the Soviet Republic they lacked the most important component, the councils." (35)

Ernst Toller, a member of the Independent Socialist Party, became a growing influence in the revolutionary council. Rosa Levine-Meyer claimed that: "Toller was too intoxicated with the prospect of playing the Bavarian Lenin to miss the occasion. To prove himself worthy of his prospective allies, he borrowed a few of their slogans and presented them to the Social Democrats as conditions for his collaboration. They included such impressive demands as: Dictatorship of the class-conscious proletariat; socialisation of industry, banks and large estates; reorganisation of the bureaucratic state and local government machine and administrative control by Workers' and Peasants' Councils; introduction of compulsory labour for the bourgeoisie; establishment of a Red Army, etc. - twelve conditions in all." (36)

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982) has pointed out: "Meanwhile, conditions for the mass of the population were getting worse daily. There were now some 40,000 unemployed in the city. A bitterly cold March had depleted coal stocks and caused a cancellation of all fuel rations. The city municipality was bankrupt, with its own employees refusing to accept its paper currency." (37)

Toller was elected as the Commander of the first Red Army to be formed on German soil. Richard Dove has pointed out: "The paradox of a pacifist poet as military commander is one which has continued to fascinate the imagination up to the present day... In fact, all his actions as military commander reveal the inherent ambivalence of his position, torn between the principle of non-violence and the imperative of revolutionary solidarity. He had joined the spontaneous defence of Munich without hesitation but not without misgiving. He saw the prospect of armed conflict as 'a tragic necessity', a phrase which runs through all his subsequent accounts. He felt 'obliged' to join the workers; the same sense of moral obligation made him accept command of the Red Army". (37a)

Eugen Levine, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), arrived in Munich from Berlin. The leadership of the KPD was determined to avoid any repetition of the events in Berlin in January, when its leaders, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, were murdered by the authorities. Levine was instructed that "any occasion for military action by government troops must be strictly avoided". Levine immediately set about reorganising the party to separate it off clearly from the anarcho-communists led by Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer. He reported back to Berlin that he had about 3,000 members of the KPD under his control. In a letter to his wife he commented that "in a few days the adventure will be liquidated". (38)

Levine pointed out that despite the Max Levien declaration, little had changed in the city: "The third day of the Soviet Republic... In the factories the workers toil and drudge as ever before for the capitalists. In the offices sit the same royal functionaries. In the streets the old armed guardians of the capitalist world keep order. The scissors of the war profiteers and the dividend hunters still snip away. The rotary presses of the capitalist press still rattle on, spewing out poison and gall, lies and calumnies to the people craving for revolutionary enlightenment... Not a single bourgeois has been disarmed, not a single worker has been armed." Levine now gave orders for over 10,000 rifles to be distributed. (39)

Inspired by the events of the October Revolution, Levine ordered the expropriated of luxury flats and gave them to the homeless. Factories were to be run by joint councils of workers and owners and workers' control of industry and plans were made to abolish paper money. Levine, like the Bolsheviks had done in Russia, established Red Guard units to defend the revolution. (40)

Levine also argued that: "We must speed up the building of revolutionary workers' organisations... We must create workers' councils out of the factory committees and the vast army of the unemployed." However, he urged caution: "We know from our experience in northern Germany that the Social Democrats often attempted to provoke premature actions which are the easiest to crush. A soviet republic cannot be proclaimed at a conference table. It is founded after a struggle by a victorious proletariat. The proletariat of Munich has not yet entered the struggle for power. After the first intoxication the Social Democrats will seize upon the first pretext to withdraw and thus deliberately betray the workers. The Independents will collaborate, then falter, then begin to waver, to negotiate with the enemy and turn unwittingly into traitors. And we as Communists will have to pay for your undertaking with blood?" (41)

Sebastian Haffner wrote in his book, Failure of a Revolution: Germany, 1918-19 (1973), that Eugen Levine was the communists best hope for leading a successful revolution as he had the same qualities as Leon Trotsky: "Eugen Levine, a young man of impulsive and wild energy who, unlike Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, probably possessed the qualities of a German Lenin or Trotsky." (42)

Johannes Hoffmann and other leaders of the Social Democratic Party in Munich fled to the town of Bamberg. Hoffman blocked food supplies to the city and began looking for troops to attack the Bavarian Soviet Republic. By the end of the week he had gathered 8,000 armed men. On 20th April, Hoffmann's forces clashed with troops led by Ernst Toller at Dachau in Upper Bavaria. After a brief battle, Hoffmann's army was forced to retreat. (43)

Eugen Levine announced that the German Communist Party had doubts about the proclamation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, but that the party would be in "the forefront of the fight" against any counter-revolutionary attempt and urged the workers to elect "revolutionary shop stewards" in order to defend the revolution. Levine argued that they should "elect men consumed with the fire of revolution, filled with energy and pugnacity, capable of rapid decision-making, while at the same time possessed of a clear view of the real power relations, thus able to choose soberly and cautiously the moment for action." (44)

Paul Frölich pointed out: "From 14 to 22 April there was a general strike, with the workers in the factories ready for any alarm. The Communists sent their feeble forces to the most important points... The administration of the city was carried on by the factory councils. The banks were blocked, each withdrawal being carefully controlled. Socialisation was not only decreed, but carried through from below in the enterprises." (45)

Hoffmann's spies were providing him with worrying reports about what was taking place in Bavaria: "Time and again one could hear in the discussions in the streets that Bavaria was called upon to promote the world revolution... These speakers were often quite reasonable people... It would be a fateful error if it were assumed that in Munich the same clear division between Spartakists and other socialists exists as for example in Berlin. For the present policy of the Communists aims constantly at uniting the whole working class against capitalism and in favour of world revolution." (46)

Johannes Hoffmann reacted by arranging for posters to appear all over Munich that proclaimed: "The Russian terror rages in Munich unleashed by alien elements. This shame must not endure for another day, another hour... Men of the Bavarian mountains, plateaux and woods, rise like one man... Head for the recruiting depots. Signed Hoffmann, Schneppenhorst." (47)

Eugen Levine pointed out that Colonel Franz Epp posed a serious threat to the revolution: "Colonel Epp is already recruiting volunteers. Students and other bourgeois youths are flocking to him from all sides. Nuremberg declared war on Munich. The gentlemen in Weimar recognise only Hoffmann's government. Noske is already whetting his butcher's knife, eager to rescue his threatened party friends and the threatened capitalists." (48)

Some of the revolutionaries realised that it was not possible to create a successful Bavarian Soviet Republic. Paul Frölich argued: "Bavaria is not economically self-sufficient. Its industries are extremely backward and the predominant agrarian population, while a factor in favour of the counter-revolution, cannot at all be viewed as pro-revolutionary. A Soviet Republic without areas of large scale industry and coalfields is impossible in Germany. Moreover the Bavarian proletariat is only in a few giant industrial plants genuinely disposed towards revolution and unhampered by petty bourgeois traditions, illusions and weaknesses." (49)

Rosa Levine-Meyer argued: "The streets were filled with workers, armed and unarmed, who marched by in detachments or stood reading the proclamations. Lorries loaded with armed workers raced through the town, often greeted with jubilant cheers. The bourgeoisie had disappeared completely; the trams were not running. All cars had been confiscated and were being used exclusively for official purposes. Thus every car that whirled past became a symbol, reminding people of the great changes. Aeroplanes appeared over the town and thousands of leaflets fluttered through the air in which the Hoffmann government pictured the horrors of Bolshevik rule and praised the democratic government who would bring peace, order and bread." (50)

Munich suffered terrible food shortages. The Red Guards sent out food patrols and did manage to steal a certain amount from the rich, but it was not enough to feed the soldiers, let alone the mass of workers. "Efforts to get more food for the poorest could lead only to clashes with the lower middle classes, which the counter-revolution was only too happy to exploit. By the end of the second week resentment began to build up even among the most radical sections of workers." (51)

On 10th April Ernst Toller made an attack on the leaders of the German Communist Party in Munich that had established the Second Bavarian Soviet Republic. He also accused Eugen Levine and Max Levien of having "absconded with the funds of the crippled war-veterans". (52) A few days later he argued: "I consider the present government a disaster for the Bavarian toiling masses. To support them would in my view compromise the revolution and the Soviet Republic." (53)

On the night of 29th April, ten prisoners, members of the Thule Society, an early fascist group, whose membership included Rudolf Hess, who had been accused of counter-revolutionary activity, were executed in the cellar of the Luitpold College. None of the Communist leaders were at that time in the building. According to Rosa Levine-Meyer this incident "unleashed tales of cut off fingers, put out eyes: the entire vocabulary of wartime atrocity came back to life... the fury within and outside the town reached its pitch." (54)

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly." (55)

The Freikorps entered Munich on 1st May, 1919. Over the next two days the Freikorps easily defeated the Red Guards. Gustav Landauer was one of the leaders who was captured during the first day of fighting. Rudolf Rocker explained what happened next: "Together with other prisoners he was loaded on a truck and taken to the jail in Starnberg. From there he and some others were driven to Stadelheim a day later. On the way he was horribly mistreated by dehumanized military pawns on the orders of their superiors. One of them, Freiherr von Gagern, hit Landauer over the head with a whip handle. This was the signal to kill the defenseless victim.... He was literally kicked to death. When he still showed signs of life, one of the callous torturers shot a bullet in his head. This was the gruesome end of Gustav Landauer - one of Germany's greatest spirits and finest men." (56)

Allan Mitchell, the author of Revolution in Bavaria (1965), pointed out: "Resistance was quickly and ruthlessly broken. Men found carrying guns were shot without trial and often without question. The irresponsible brutality of the Freikorps continued sporadically over the next few days as political prisoners were taken, beaten and sometimes executed." An estimated 700 men and women were captured and executed. (57)

Ernst Toller was arrested and charged with high treason. Toller, who served as President of the Bavarian Soviet Republic between 6th and 12th April and was expected to be found guilty and sentenced to death but his friends began an international campaign to save his life. Max Weber, Thomas Mann and Max Halbe, gave evidence on his behalf in court. Wolfgang Heine, a leading figure in the Social Democratic Party and the Prussian Minister of the Interior, wrote to the court that he could "say nothing but good about Toller's character", calling him "an incorrigible optimist... who rejects all violence" and concluding that "his execution could have only the most unfortunate consequences". (57a)

At his trial Toller argued: "We revolutionaries acknowledge the right to revolution when we see that the situation is no longer tolerable, that it has become a frozen. Then we have the right to overthrow it. The working class will not halt until socialism has been realized. The revolution is like a vessel filled with the pulsating heartbeat of millions of working people. And the spirit of revolution will not die while the hearts of these workers continue to beat. Gentlemen! I am convinced that, by your own lights, you will pronounce judgement to the best of your knowledge and belief. But knowing my views you must also accept that I shall regard your verdict as the expression, not of justice, but of power." (58)

Toller, who served as President of the Bavarian Soviet Republic between 6th and 12th April and was expected to be found guilty and sentenced to death but his friends began an international campaign to save his life. Max Weber and Thomas Mann gave evidence on his behalf in court and although Toller was found guilty of high treason, the judge acknowledged his "honourable motives" and sentenced him to only five years in prison.

Eugen Levine, was arrested by the authorities on 12th May, 1919. Levine's cell was left open in the hope that he would be beaten to death. According to his wife: "Soldiers were constantly patrolling the corridors, entering his cell and keeping him in a state of great suspense." A warder told his wife that "we were told that your husband ordered the execution of 10,000 prison warders and policeman." According to his wife "he was heavily chained and the door of his cell stood wide open, positively inviting an assault." (59)

In court Levine defended his actions: "The Proletarian Revolution has no need of terror for its aims; it detests and abhors murder. It has no need of these means of struggle, for it fights not individuals but institutions. How then does the struggle arise? Why, having gained power, do we build a Red Army? Because history teaches us that every privileged class has hitherto defended itself by force when its privileges have been endangered. And because we know this; because we do not live in cloud-cuckoo-land; because we cannot believe that conditions in Bavaria are different - that the Bavarian bourgeoisie and the capitalists would allow themselves to be expropriated without a struggle - we were compelled to arm the workers to defend ourselves against the onslaught of the dispossessed capitalists."

Eugen Levine accepted that the court would order his execution: "We Communists are all dead men on leave. Of this I am fully aware. I do not know if you will extend my leave or whether I shall have to join Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In any case I await your verdict with composure and inner serenity. For I know that, whatever your verdict, events cannot be stopped... Pronounce your verdict if you deem it proper. I have only striven to foil your attempt to stain my political activity, the name of the Soviet Republic with which I feel myself so closely bound up, and the good name of the workers of Munich. They - and I together with them - we have all of us tried to the best of our knowledge and conscience to do our duty towards the International, the Communist World Revolution." (60)

The Münchener Post reported: "Levine faced the Court on the second day of the trial with an indifference to the fate hanging over him which alone could shatter the indictment of cowardice by the Public Prosecutor. The unstudied posture of the defendant undoubtedly impressed many of those who had not experienced the Levine of the second Soviet Republic. Levine relieved his Counsel of the task of defending him. In his final speech, which put into the shade all the rhetoric of his professional advocates, he resolutely swept aside all the little tricks which his Counsel brought forward in his favour. Lucid, calm and to the point the speech was more effective than all that had been said in his defence during the long preceding hours. Once again it became evident that he possessed courage wrongfully denied to him, that he skilfully remained master of the situation, that he succeeded with a superiority of his own, in crystallising all those points which ensured him his influence on the masses." (61)

In court Levine was defended by Count Alberto Pestalozza, a member of the Catholic Centre Party. He argued: "Don't send this man to his death, for should you do so, he would not die, he would start to live again. The life of this man would lie on the conscience of the entire community and his ideas would generate the seed of terrible revenge." However, Levine was sentenced to death on 3rd June, 1919.

The Frankfurter Zeitung wrote that it was the duty of the Social Democrat Party government to prevent the execution "by every means, even at the risk of evoking a cabinet crisis." The Berliner Neue Zeitung, which denounced Levine as "the seducer of the Munich proletariat" called for him to be reprieved: "Wide circles, from the government down to the non-socialist community, left no doubt that under the prevailing political conditions, which were the background of Levine's crimes, the application of mercy and political wisdom would be more more appropriate than punishment. Both socialist parties, usually at loggerheads, agreed that this was a case which simply cried out for a reprieve." (62)

Primary Sources

(1) Eric Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920)

The proud German Army, after victoriously resisting an enemy superior in numbers for four years, performing feats unprecedented in history, and keeping our foes from our frontiers, disappeared in a moment. Our victorious fleet was handed over to the enemy. The authorities at home, who had not fought against the enemy, could not hurry fast enough to pardon deserters and other military criminals, including among these many of their own number, themselves and their nearest friends.

They and the Soldiers' Councils worked with zeal, determination and purpose to destroy the whole military structure. Such was the gratitude of the new homeland to the German soldiers who had bled and died for it in millions. The destruction of Germany's power to defend herself - the work of Germans - was the most tragic crime the world has witnessed. A tidal wave had broken over Germany, not by the force of nature, but through the weakness of the Government, represented by the Chancellor, and the paralysis of a leaderless people.

(2) Bertram D. Wolfe, Strange Communists I Have Known (1966)

In the third week of December, the masses, as represented in the First National Congress of the Councils of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, rejected by an overwhelming majority the Spartacan motion that the Councils should disrupt the Constituent Assembly and the Provisional Democratic Government and seize power themselves.

In the light of Rosa's public pledge, the duty of her movement seemed clear: to accept the decision, or to seek to have it reversed not by force but by persuasion. However, on the last two days of 1918 and the first of 1919, the Spartacans held a convention of their own where they outvoted their "leader" once more. In vain did she try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising. Almost alone in her party, Rosa Luxemburg decided with a heavy heart to lend her energy and her name to their effort.

The Putsch, with inadequate forces and overwhelming mass disapproval except in Berlin, was as she had predicted, a fizzle. But neither she nor her close associates fled for safety as Lenin had done in July, 1917. They stayed in the capital, hiding carelessly in easily suspected hideouts, trying to direct an orderly retreat. On January 16, a little over two months after she had been released from prison, Rosa Luxemburg was seized, along with Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck. Reactionary officers murdered Liebknecht and Luxemburg while "taking them to prison." Pieck was spared, to become, as the reader knows, one of the puppet rulers of Moscow-controlled East Germany.

(3) Paul Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940)

A short while after Liebknecht had been taken away, Rosa Luxemburg was led out of the hotel by a First Lieutenant Vogel. Awaiting her before the door was Runge, who had received an order from First Lieutenants Vogel and Pflugk-Hartung to strike her to the ground. With two blows of his rifle-butt he smashed her skull.

Her almost lifeless body was flung into a waiting car, and several officers jumped in. One of them struck Rosa on the head with a revolver-butt, and First Lieutenant Vogel finished her off with a shot in the head. The corpse was then driven to the Tiergarten and, on Vogel's orders, thrown from the Liechtenstein Bridge into the Landwehr Canal, where it was not washed up until 31 May 1919.

(4) Ernst Toller, speech at his trial for high treason (14th July, 1919)

We revolutionaries acknowledge the right to revolution when we see that the situation is no longer tolerable, that it has become a frozen. Then we have the right to overthrow it.

The working class will not halt until socialism has been realized. The revolution is like a vessel filled with the pulsating heartbeat of millions of working people. And the spirit of revolution will not die while the hearts of these workers continue to beat.

Gentlemen! I am convinced that, by your own lights, you will pronounce judgement to the best of your knowledge and belief. But knowing my views you must also accept that I shall regard your verdict as the expression, not of justice, but of power.

(5) Chris Harman, The Lost Revolution (1982)

On 7th November, 1918, the city was paralysed by the strike. Auer (the SDP leader) turned up to address what he expected to be a peaceful demonstration, to find the most militant section of it composed of armed soldiers and sailors, gathered behind the bearded Bohemian figure of Eisner and a huge banner reading Long Live the Revolution. While the Social Democrat leaders stood aghast, wondering what to do, Eisner led his group off, drawing much of the crowd behind it, and made a tour of the barracks. Soldiers rushed to the windows at the sound of the approaching turmoil, exchanged quick words with the demonstrators, picked up their guns and flocked in behind.

(6) Eugen Levine, speech (4th April, 1919)

I have just learned of your plans. We Communists harbour profound suspicion of a soviet republic initiated by the Social Democrat minister Schneppenhorst and men like Durr, who up to now have combated the soviet system with all their power. At best we can interpret their attitude as the attempt of bankrupt leaders to ingratiate themselves with the masses by seemingly revolutionary action, or worse, as a deliberate provocation.

We know from our experience in northern Germany that the Social Democrats often attempted to provoke premature actions which are the easiest to crush.

A soviet republic cannot be proclaimed at a conference table. It is founded after a struggle by a victorious proletariat. The proletariat of Munich has not yet entered the struggle for power.

After the first intoxication the Social Democrats will seize upon the first pretext to withdraw and thus deliberately betray the workers. The Independents will collaborate, then falter, then begin to waver, to negotiate with the enemy and turn unwittingly into traitors. And we as Communists will have to pay for your undertaking with blood?

(7) Rosa Levine-Meyer, Levine: The Life of a Revolutionary (1973)

The streets were filled with workers, armed and unarmed, who marched by in detachments or stood reading the proclamations. Lorries loaded with armed workers raced through the town, often greeted with jubilant cheers.

The bourgeoisie had disappeared completely; the trams were not running. All cars had been confiscated and were being used exclusively for official purposes. Thus every car that whirled past became a symbol, reminding people of the great changes.

Aeroplanes appeared over the town and thousands of leaflets fluttered through the air in which the Hoffmann government pictured the horrors of Bolshevik rule and praised the democratic government who would bring peace, order and bread.

(8) Eric Hobsbawm, The German Revolution (1973)

In Bavaria, hardly a stronghold of the labour movement, the revolution under the leadership of the Independent Social Democrat Kurt Eisner and a peasant leader, each representing quite small organisations, had demonstrated what it might have achieved in Germany. Eisner became prime minister of a Bavarian Republic, supported by all sections of the left, and attempted a sort of combination of a democratic constitution with a republic of the councils. This left-wing regime survived the collapse of the revolution in Berlin and most other parts of the country, but Eisner was assassinated in February 1919 by an ultra-reactionary, Count Arco. To this part of Germany the Communist Party sent Eugen Levine. Here he participated in, and attempted to introduce some element of serious organisation and effectiveness into, the Bavarian Soviet Republic of April 1919.

It is possible, though perhaps not very likely, that Bavaria could have maintained itself as an autonomous and relatively left-wing regime, based on the unity of its labour movement and the proverbial dislike of Bavarians for going the way of the rest of Germany. At all events Berlin hesitated to intervene against it. But a Soviet Republic was doomed. Levine himself was opposed to it. After the proclamation of the Hungarian Soviet Republic on March 21, 1919, however a wave of utopian hope swept across the Bavarian movement. If they gave another signal, would not Austria also rise and a central European soviet zone come into existence? A Soviet Republic was proclaimed in Munich and enthusiastically joined by the numerous, often anarchist and semi-anarchist writers and intellectuals of what was Germany's most celebrated Latin Quarter. Levine, a lucid, sceptical, efficient professional of revolution among noble amateurs living out the dream of liberation and confused militants, knew that it was lost, but also that it had to fight. Though not lacking in at least passive support among the Munich workers, the Soviet Republic horrified the conservative and Catholic peasantry and the notably reactionary middle class of Bavaria to the point where they welcomed the joint invasion of government troops and Free Corps from all over Germany (including a Bavarian Free Corps). The Soviet Republic ended on May 1 and was drowned in blood. Eugen Levine its ablest leader, was one of the victims.

He died comparatively young, and it is impossible to say what this impressive Russian, a figure closer by origin and sympathy to Lenin's Bolsheviks than to most German revolutionaries of the time, would have achieved had he lived. There is little point in speculating about it. We can only welcome this most valuable memoir in which his widow has made him live again for us, and incidentally provided a notable addition to our knowledge of the German tragedy of 1918-19, and to our understanding of the revolutionaries and revolutions of our century.

(9) Sebastian Haffner, Failure of a Revolution: Germany, 1918-19 (1973)

Never before was a revolutionary party forced into action in an inflammable situation against its will and with such cynicism. Never were the militant workers so severely punished for it. Never was a game so clearly envisaged by a superior, not only "equal" opponent. Never had a revolutionary party resisted with such determination taking part in an ostensibly revolutionary action. Never had a revolutionary party to master such a bizarre, daily changing situation.

(10) Rudolf Rocker, Gustav Landauer (1919)

After the end of the first council republic, which he had dedicated his rich knowledge and abilities to wholeheartedly, Landauer lived with the widow of his good friend Kurt Eisner. He was arrested in her house on the afternoon of May 1. Close friends had urged him to escape a few days earlier. Then it would have still been a fairly easy thing to do. But Landauer decided to stay. Together with other prisoners he was loaded on a truck and taken to the jail in Starnberg. From there he and some others were driven to Stadelheim a day later. On the way he was horribly mistreated by dehumanized military pawns on the orders of their superiors. One of them, Freiherr von Gagern, hit Landauer over the head with a whip handle. This was the signal to kill the defenseless victim. An eyewitness later said that Landauer used his last strength to shout at his murderers: "Finish me off - to be human!' He was literally kicked to death. When he still showed signs of life, one of the callous torturers shot a bullet in his head. This was the gruesome end of Gustav Landauer - one of Germany's greatest spirits and finest men.

(11) Rosa Levine-Meyer, Levine: The Life of a Revolutionary (1973)

The executive of the Social-Democratic Party vouched that "the troops of Hoffmann's Socialist Government are not enemies of the workers, not White Guards. They come to safeguard public order and security."

Only a handful of workers rallied to resist the onslaught. as Levine predicted: "There will always be a number of foolhardy heroes ready to fight for their lives and defend the honour of the revolution."

According to official figures, no more than 93 members of the Red Army and 38 soldiers fell in battle.

Nevertheless, the military operation lasted several days. To achieve security and order of their type it was essential to thoroughly "smoke out the Spartacists' nests." According to official estimates this operation cost 370 lives. Other sources more qualified and objective put the number of victims into the 600-700 bracket.

(12) Eugen Levine, speech in court (2nd June, 1919)

The Proletarian Revolution has no need of terror for its aims; it detests and abhors murder. It has no need of these means of struggle, for it fights not individuals but institutions. How then does the struggle arise? Why, having gained power, do we build a Red Army? Because history teaches us that every privileged class has hitherto defended itself by force when its privileges have been endangered. And because we know this; because we do not live in cloud-cuckoo-land; because we cannot believe that conditions in Bavaria are different - that the Bavarian bourgeoisie and the capitalists would allow themselves to be expropriated without a struggle - we were compelled to arm the workers to defend ourselves against the onslaught of the dispossessed capitalists...

I am coming to a close. During the last six months I have no longer been able to live with my family. Occasionally my wife could not even visit me. I could not see my three-year-old boy because the police have kept a vigilant watch on us.

Such was my life and it is not compatible with lust for power or with cowardice. When Toller, who tried to persuade me to proclaim the Soviet Republic, in his turn accused me of cowardice, I said to him: "What do you want? The Social Democrats start, then run away and betray us; the Independents fall for the bait, join us, and later let us down, and we Communists are stood up against the wall."

We Communists are all dead men on leave. Of this I am fully aware. I do not know if you will extend my leave or whether I shall have to join Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In any case I await your verdict with composure and inner serenity. For I know that, whatever your verdict, events cannot be stopped. The Prosecuting Counsel believes that the leaders incited the masses. But just as leaders could not prevent the mistakes of the masses under the pseudo-Soviet Republic, so the disappearance of one or other of the leaders will under no circumstances hold up the movement.

And yet I know, sooner or later other judges will sit in this Hall and then those will be punished for high treason who have transgressed against the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Pronounce your verdict if you deem it proper. I have only striven to foil your attempt to stain my political activity, the name of the Soviet Republic with which I feel myself so closely bound up, and the good name of the workers of Munich. They - and I together with them - we have all of us tried to the best of our knowledge and conscience to do our duty towards the International, the Communist World Revolution.

Student Activities

Who Set Fire to the Reichstag? (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)