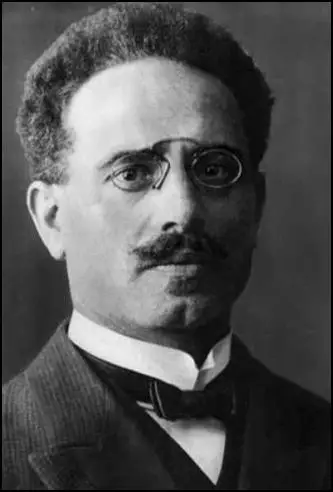

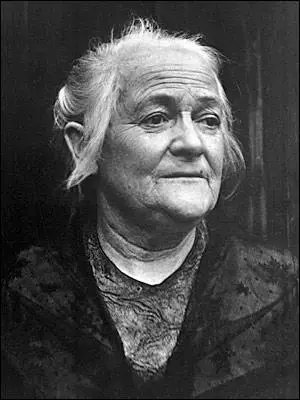

Clara Zetkin

Clara Eissner, the daughter of Gottfried Eissner, a local schoolmaster, was born in Wiederau, Saxony, on 5th July, 1857. While studying at Leipzig Teacher's College for Women she became a socialist and feminist. (1)

In 1875 August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht, the founders of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP), merged it with the General German Workers' Association (ADAV), an organisation led by Ferdinand Lassalle, to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Clara was one of those who joined the new party. In the 1877 General Election in Germany the SDP won 12 seats. This worried Otto von Bismarck, and in 1878 he introduced an anti-socialist law which banned SDP meetings and publications. (2)

Clara, like other members of the SDP left for Zurich in 1882 and then moved on to live in exile in Paris. During this period Clara read Woman and Socialism. In the book August Bebel argued that it was the goal of socialists "not only to achieve equality of men and women under the present social order, which constitutes the sole aim of the bourgeois women's movement, but to go far beyond this and to remove all barriers that make one human being dependent upon another, which includes the dependence of one sex upon another." She later wrote that out of this book "streams of life poured forth; thus it was that his great firmness in principles and tactics did not appear as dry, rigid dogmatism, but seemed, on the contrary, to breathe forth the natural freshness of life itself." (3)

A strong supporter of international socialism, Clara married Ossip Zetkin, a Russian revolutionary who was living in exile. Ossip was a carpenter, a Marxist, and according to her mother was a "good-for-nothing". In 1883, her son Maxim, was born, followed by Kostya in 1885. In Paris she met other leading socialists from France, Germany and Russia. She was active politically, worked as a journalist and took up a role of "teacher and Educator". (4)

Clara and Ossip Zetkin became members of the international socialist group, Cercle Internationale, which met weekly to discuss questions of Marxist theory and to plan action. "Here the Zetkins came into contact not only with Russian, German and French socialists, but with socialists from Spain, Italy, Austria and Britain as well. It was in this period that Clara Zetkin gained her vast knowledge of the international labour movement, as well as her proficiency in a number of languages." Ossip Zetkin died of tuberculosis in January, 1889. (5)

Clara Zetkin - International Socialist

Ossip Zetkin died of tuberculosis in January, 1889. Clara continued with her political campaigns. She refused to join the Berlin Association of Proletarian Women and Girls because it accepted only women as members. Clara disapproved of the "segregation of women and men" and regretted the "feminist tendencies... of many outstanding supporters of the Berlin movement". Zetkin was initially critical of the demand for female suffrage because "without economic freedom it changes absolutely nothing". She saw it as being a middle-class movement. (6)

Zetkin took a particular interest in supporting women workers in their demand for higher wages: "What made women's labour particularly attractive to the capitalists was not only its lower price but also the greater submissiveness of women. The capitalists speculate on the two following factors: the female worker must be paid as poorly as possible and the competition of female labour must be employed to lower the wages of male workers as much as possible. In the same manner the capitalists use child labour to depress women's wages and the work of machines to depress all human labour." (7)

After the anti-socialist law ceased to operate in 1890, Zetkin returned to Germany. Membership grew rapidly but August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht had problems with divisions in the party. Eduard Bernstein, a member of the SDP, who had been living in London, became convinced that the best way to obtain socialism in an industrialized country was through trade union activity and parliamentary politics. He published a series of articles where he argued that the predictions made by Karl Marx about the development of capitalism had not come true. He pointed out that the real wages of workers had risen and the polarization of classes between an oppressed proletariat and capitalist, had not materialized. Nor had capital become concentrated in fewer hands. (8)

Eduard Bernstein's revisionist views appeared in his extremely influential book Evolutionary Socialism (1899). His analysis of modern capitalism undermined the claims that Marxism was a science and upset leading revolutionaries such as Lenin and Leon Trotsky. In 1900, Rosa Luxemburg published an attack on Bernstein in her pamphlet, Reform or Revolution. (9)

Luxemburg argued: "He (Bernstein), who wants to pass as a socialist, and at the same time declare war on Marxian doctrine, the most stupendous product of the human mind in the century, must begin with involuntary esteem for Marx. He must begin by acknowledging himself to be his disciple, by seeking in Marx’s own teachings the points of support for an attack on the latter, while he represents this attack as a further development of Marxian doctrine. On this account, we must, unconcerned by its outer forms, pick out the sheathed kernel of Bernstein’s theory. This is a matter of urgent necessity for the broad layers of the industrial proletariat in our Party." (10)

In 1891 Clara Zetkin became editor of the SPD's journal, Die Gleichheit (Equality). An impressive journalist, Zetkin took the circulation from 11,000 in 1903 to 67,000 three years later. Zetkin now changed her views on women's suffrage and helped to organize the first International Conference of Socialist Women in Struttgart. The conference was attended by 58 female delegates from 15 countries in Europe. During the conference "the socialist parties of all countries committed themselves to energetically championing female suffrage without any restrictions." This was in contrast to middle class women who were willing to accept "restricted female suffrage" or "ladies' suffrage". (11)

Anti-Militarism

Karl Liebknecht was a leading figure in the anti-militarist section of the SDP. In 1907 he published Militarism and Anti-Militarism. In the book he argued: "Militarism is not specific to capitalism. It is moreover normal and necessary in every class-divided social order, of which the capitalist system is the last. Capitalism, of course, like every other class-divided social order, develops its own special variety of militarism; for militarism is by its very essence a means to an end, or to several ends, which differ according to the kind of social order in question and which can be attained according to this difference in different ways. This comes out not only in military organization, but also in the other features of militarism which manifest themselves when it carries out its tasks. The capitalist stage of development is best met with an army based on universal military service, an army which, though it is based on the people, is not a people’s army but an army hostile to the people, or at least one which is being built up in that direction."

Liebknecht then went on to argue why the socialist movement should concentrate on persuading young people to adopt the philosophy of anti-militarism: "Here is a great field full of the best hopes of the working-class, almost incalculable in its potential, whose cultivation must not at any cost wait upon the conversion of the backward sections of the adult proletariat. It is of course easier to influence the children of politically educated parents, but this does not mean that it is not possible, indeed a duty, to set to work also on the more difficult section of the proletarian youth. The need for agitation among young people is therefore beyond doubt. And since this agitation must operate with fundamentally different methods – in accordance with its object, that is, with the different conditions of life, the different level of understanding, the different interests and the different character of young people – it follows that it must be of a special character, that it must take a special place alongside the general work of agitation, and that it would be sensible to put it, at least to a certain degree, in the hands of special organizations." (12)

At this time Germany became involved in an arms race with Britain. The Royal Navy built its first dreadnought in 1906. It was the most heavily-armed ship in history. She had ten 12-inch guns (305 mm), whereas the previous record was four 12-inch guns. The gun turrets were situated higher than user and so facilitated more accurate long-distance fire. In addition to her 12-inch guns, the ship also had twenty-four 3-inch guns (76 mm) and five torpedo tubes below water. In the waterline section of her hull, the ship was armoured by plates 28 cm thick. It was the first major warship driven solely by steam turbines. It was also faster than any other warship and could reach speeds of 21 knots. A total of 526 feet long (160.1 metres) it had a crew of over 800 men. It cost over £2 million, twice as much as the cost of a conventional battleship.

Germany built its first dreadnought in 1907 and plans were made for building more. Kaiser Wilhelm II gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph in October 1908 where he outlined his policy of increasing the size of his navy: "Germany is a young and growing empire. She has a world-wide commerce which is rapidly expanding and to which the legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds. Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect that commerce and her manifold interests in even the most distant seas. She expects those interests to go on growing, and she must be able to champion them manfully in any quarter of the globe. Her horizons stretch far away. She must be prepared for any eventualities in the Far East. Who can foresee what may take place in the Pacific in the days to come, days not so distant as some believe, but days at any rate, for which all European powers with Far Eastern interests ought steadily to prepare?" (13)

Karl Liebknecht led the campaign against the building of more dreadnoughts. Other members of the Social Democratic Party who supported Liebknecht became known as the Left Radicals. This included Leo Jogiches, Franz Mehring, Clara Zetkin, Paul Frölich, Hugo Eberlein, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker, Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Anton Pannekoek. The leadership of the SDP agreed with the build-up of the armed forces in Germany and they saw a significant growth in their popularity. For example, in 1907 they won 43 seats in the Reichstag. Four years later they increased this to 110 seats. (14)

Outbreak of the First World War

On 4th August, 1914, Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy." (15)

Paul Frölich, a supporter of Liebknecht in the Social Democratic Party (SDP), argued: "On the day of the vote only one man was left: Karl Liebknecht. Perhaps that was a good thing. That only one man, one single person, let it be known on a rostrum being watched by the whole world that he was opposed to the general war madness and the omnipotence of the state - this was a luminous demonstration of what really mattered at the moment: the engagement of one's whole personality in the struggle. Liebknecht's name became a symbol, a battle-cry heard above the trenches, its echoes growing louder and louder above the world-wide clash of arms and arousing many thousands of fighters against the world slaughter." (16)

John Peter Nettl claims that two left-wing members of the SDP, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin, were horrified by these events. They had great hopes that the SDP, the largest socialist party in the world with over a million members, would oppose the war: "Both Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin suffered nervous prostration and were at one moment near to suicide. Together they tried on 2 and 3 August to plan an agitation against the war; they contacted 20 SPD members with known radical views, but they got the support of only Liebknecht and Mehring... Rosa sent 300 telegrams to local officials who were thought to be oppositional, asking their attitude to the vote in the Reichstag and inviting them to Berlin for an urgent conference. The results were pitiful." (17)

Clara Zetkin later recalled: "The struggle was supposed to begin with a protest against the voting of war credits by the social-democratic Reichstag deputies, but it had to be conducted in such a way that it would be throttled by the cunning tricks of the military authorities and the censorship. Moreover, and above all, the significance of such a protest would doubtless be enhanced, if it was supported from the outset by a goodly number of well-known social-democratic militants.... Out of all those out-spoken critics of the social-democratic majority, only Karl Liebknecht joined with Rosa Luxemburg, Franz Mehring, and myself in defying the soul-destroying and demoralising idol into which party discipline had developed." (18)

International Peace Movement

Clara Zetkin joined forces with Rosa Luxemburg, Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Hugo Eberlein to campaign against the war but decided against forming a new party and agreed to continue working within the SPD. Clara Zetkin was initially reluctant to join the group. She argued: "We must ensure the broadest relationship with the masses. In the given situation the protest appears more as a personal beau geste than a political action... It is justified and nice to say that everything is lost, except one's honour. If I wanted to follow my feelings, then I would have telegraphed a yes with great pleasure. But now we must more than ever think and act coolly." (19)

However, by September, 1914, Zetkin was playing a significant role in the anti-war movement. She co-signed with Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Mehring, letters that appeared in socialist newspapers in neutral countries condemning the war. Above all Zetkin used her position as editor-in-chief of the Die Gleichheit (Equality) and as Secretary of the Women's Secretariat of the Socialist International to propagate the positions of the anti-war movement. (20)

Zetkin became very disillusioned with the growing nationalism of the Social Democratic Party. She wrote to her friend, Helen Ankersmit, about her concerns: "The most disastrous phenomenon of the current situation is the factor that imperialism is employing for its own ends all the powers of the proletariat, all of its institutions and weapons, which its fighting vanguard has created for its war of liberation. Social Democracy bears the main guilt and responsibility for this phenomenon before the International and history. The granting of the war credits was the harbinger for the equally comprehensive and revolting process of capitulation of German Social Democracy". (21)

Karl Liebknecht continued to make speeches in public about the war: "The war is not being waged for the benefit of the German or any other peoples. It is an imperialist war, a war over the capitalist domination of the world market... The slogan 'against Tsarism' is being used - just as the French and British slogan 'against militarism' - to mobilise the noble sentiments, the revolutionary traditions and the hopes of the people for the national hatred of other peoples." (22)

Clara Zetkin became involved in the Women's Peace Party that attempted to bring an end to the war. Other members included Mary Sheepshanks, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Chrystal Macmillan. Sylvia Pankhurst, Charlotte Despard, Helena Swanwick, Olive Schreiner, Helen Crawfurd, Alice Wheeldon, Jane Addams, Emily Greene Balch, Lida Gustava Heymann, Rosika Schwimmer; Aletta Jacobs and Emilia Fogelklou.

At a International Women's Peace Conference in March, 1915, at the Hague, Clara Zetkin argued: "Who profits from this war? Only a tiny minority in each nation: The manufacturers of rifles and cannons, of armor-plate and torpedo boats, the shipyard owners and the suppliers of the armed forces' needs. In the interests of their profits, they have fanned the hatred among the people, this contributing to the outbreak of the war. The workers have nothing to gain from this war, but they stand to lose everything that is dear to them." (23)

In May 1915, Karl Liebknecht published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued that: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity." (24)

In December, 1915, 19 other deputies joined Karl Liebknecht in voting against war credits. The following year a series of demonstrations took place. Some of these were "spontaneous outbursts by unorganised groups of people, usually women: anger would flare when a shop ran out of food, or put its prices up, or when rations were suddenly cut." These demonstrations often led to bitter clashes between workers and the police. (25)

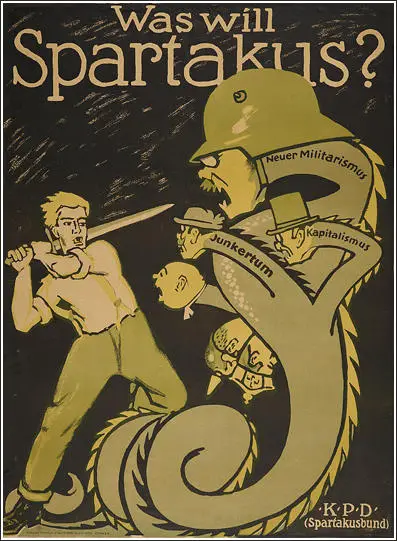

The Spartacus League

Rosa Luxemburg continued to protest against Germany's involvement in the war and on the 19th February, 1915, she was arrested. As a political prisoner she was allowed books and writing materials. With the help of Mathilde Jacob she was able to smuggle out articles and pamphlets she had written to Franz Mehring. In April 1915, Mehring published some of this material in a new journal, Die Internationale.

Other contributors included Clara Zetkin, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker and Heinrich Ströbel. The journal included articles by Mehring on the attitude of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to the problem of war and Zetkin dealt with the position of women in wartime. The main objective of the journal was to criticise the official policy of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) towards the First World War. (26)

Over the next few months members of this group were arrested for their anti-war activities and spent several short spells in prison. This included Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck and Hugo Eberlein. Other activists included Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi, Julian Marchlewski and Hermann Duncker. On the release of Luxemburg in February 1916, it was decided to establish an underground political organization called Spartakusbund (Spartacus League). The Spartacus League publicized its views in its illegal newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Like the Bolsheviks in Russia, they argued that socialists should turn this nationalist conflict into a revolutionary war. (27)

The group published an attack on all European socialist parties (except the Independent Labour Party): "By their vote for war credits and by their proclamation of national unity, the official leaderships of the socialist parties in Germany, France and England (with the exception of the Independent Labour Party) have reinforced imperialism, induced the masses of the people to suffer patiently the misery and horrors of the war, contributed to the unleashing, without restraint, of imperialist frenzy, to the prolongation of the massacre and the increase in the number of its victims, and assumed their share in the responsibility for the war itself and for its consequences." (28)

Eugen Levine was one of the first people to join the Spartacus League. He had been disturbed by the "new wave of national prejudice and chauvinism". His wife, Rosa Levine-Meyer, was shocked when he stated that the war would last "at least eighteen months or two years". This upset his mother who had been convinced by government propaganda that "the war would end by Christmas". Levine told Rosa that the "war would be accompanied by a severe world crisis and revolutionary shocks". He added that during a war "it is easier to convert thousands of workers than one single well-meaning intellectual". (29)

On 1st May, 1916, Rosa Luxemburg, organised a anti-war demonstration on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. It was a great success and by eight o'clock in the morning around 10,000 people assembled in the square. The police charged at Karl Liebknecht who was about to speak to the large crowd. "For two hours after Liebknecht's arrest masses of people swirled around Potsdamer Platz and the neighbouring streets, and there were many scuffles with the police. For the first time since the beginning of the war open resistance to it had appeared on the streets of the capital." (30)

As a member of the Reichstag, Liebknecht had parliamentary immunity from prosecution. When the military judicial authorities demanded that this immunity was removed, the Reichstag agreed and he was placed on trial. On 28th June 1916, Liebknecht was sentenced to two years and six months hard labour. The day Liebknecht was sentenced, 55,000 munitions workers went on strike. The government responded by arresting trade union leaders and having them conscripted into the German Army.

Luxemburg responded by publishing a handbill defending Liebknecht and accusing members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) who had removed his parliamentary immunity as being "political dogs". She claimed that: "A dog is someone who licks the boots of the master who has dealt him kicks for decades. A dog is someone who gaily wags his tail in the muzzle of martial law and looks straight into the eyes of the lords of the military dictatorship while softly whining for mercy... A dog is someone who, at his government's command, abjures, slobbers, and tramples down into the muck the whole history of his party and everything it has held sacred for a generation." (31)

Rosa Luxemburg was re-arrested on 10th July, 1916. So also was the seventy-year-old Franz Mehring, Ernest Meyer and Julian Marchlewski. Leo Jogiches now became the leader of the Spartacus League and the editor of its newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Luxemburg, wrote regularly for each edition, sometimes writing three-quarters of a whole issue. She also worked on her book, Introduction to Economics. (32)

The German Revolution

In April 1917 Clara Zetkin left the Spartacus League and along with other left-wing members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) formed the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Members included Kurt Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Emil Barth, Julius Leber, Ernst Toller, Ernst Thälmann, Rudolf Breitscheild, Emil Eichhorn, Kurt Rosenfeld, Ernst Torgler and Rudolf Hilferding.

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a ceasefire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (33)

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace." (34)

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Keil soon travelled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power." (35)

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks." (36)

Chancellor, Max von Baden, decided to hand over power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy: "You have no right to proclaim the republic." (37)

Karl Liebknecht, who had been released from prison on 23rd October, climbed to a balcony in the Imperial Palace and made a speech: "The day of Liberty has dawned. I proclaim the free socialist republic of all Germans. We extend our hand to them and ask them to complete the world revolution. Those of you who want the world revolution, raise your hands." It is claimed that thousands of hands rose up in support of Liebknecht. (38)

The Social Democratic Party press, fearing the opposition of the left-wing and anti-war Spartacus League, proudly trumpeted their achievements: "The revolution has been brilliantly carried through... the solidarity of proletarian action has smashed all opposition. Total victory all along the line. A victory made possible because of the unity and determination of all who wear the workers' shirt." (39)

Friedrich Ebert established the Council of the People's Deputies, a provisional government consisting of three delegates from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and three from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Liebknecht was offered a place in the government but he refused, claiming that he would be a prisoner of the non-revolutionary majority. A few days later Ebert announced elections for a Constituent Assembly to take place on 19th January, 1918. Under the new constitution all men and women over the age of 20 had the vote. (40)

As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League." (41)

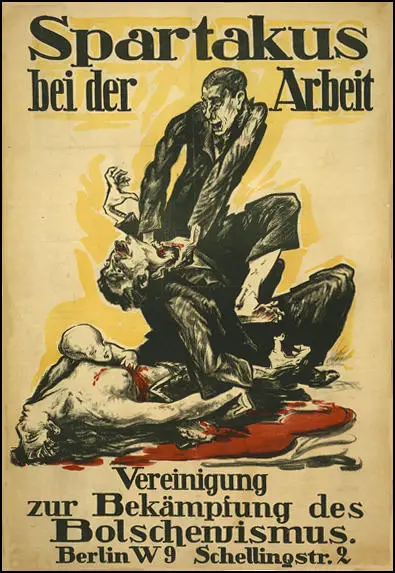

Friedrich Ebert decided to destroy the Spartacus League in Berlin who had attempted to gain power by force. He made contact with General Wilhelm Groener, who as First Quartermaster General, had played an important role in the retreat and demobilization of the German armies. According to William L. Shirer, the SDP leader and the "second-in-command of the German Army made a pact which, though it would not be publicly known for many years, was to determine the nation's fate. Ebert agreed to put down anarchy and Bolshevism and maintain the Army in all its tradition. Groener thereupon pledged the support of the Army in helping the new government establish itself and carry out its aims." (42)

On the 5th January, Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. Groener later testified that his aim in reaching accommodation with Ebert was to "win a share of power in the new state for the army and the officer corps... to preserve the best and strongest elements of old Prussia". Ebert was motivated by his fear of the Spartacus League and was willing to use "the armed power of the far-right to impose the government's will upon recalcitrant workers, irrespective of the long-term effects of such a policy on the stability of parliamentary democracy". (43)

The soldiers who entered Berlin were armed with machine-guns and armoured cars and demonstrators were killed in their hundreds. Artillery was used to blow the front off the police headquarters before Eichhorn's men abandoned resistance. "Little quarter was given to its defenders, who were shot down where they were found. Only a few managed to escape across the roofs." (44)

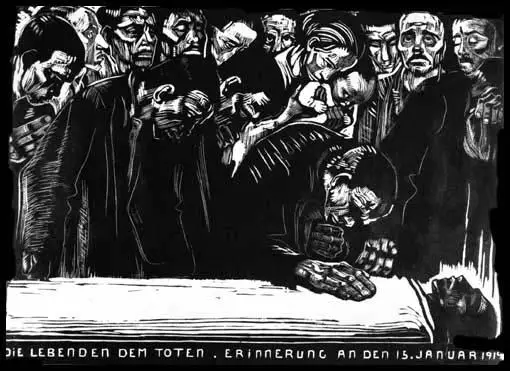

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal." (45)

Clara Zetkin was one of twenty-two members of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) elected to the Constituent Assembly. The German Social Democrat Party won 163 of a total of 421, and dominated the new national government. On 29th January 1919, she was the first woman to speak in a German parliament. In the speech she delivered an attack on Friedrich Ebert and his government for the way he had dealt with the Spartacus League. (46)

Leo Jogiches was executed on 10th March, 1919. Clara Zetkin wrote to Lenin on 8th April: "The murder of Karl (Liebknecht) and especially Rosa (Luxemburg) was a terrible blow. Leo's death has taken from me the last of the small group in which we have been fighting together... Of the four who first protested against the world war and fought for the revolution I am now the only one alive and in Germany I feel completely orphaned." (47)

In May, 1919, Clara Zetkin, wrote an article, about her long-term colleague, Rosa Luxemburg, who had been murdered by the Freikorps. "Rosa Luxemburg the socialist idea was a dominating and powerful passion of both mind and heart, a consuming and creative passion. To prepare for the revolution, to pave the way for socialism - this was the task and the one great ambition of this exceptional woman. To experience the revolution, to fight in its battles - this was her highest happiness. With will-power, selflessness and devotion, for which words are too weak, she engaged her whole being and everything she had to offer for socialism. She sacrificed herself to the cause, not only in her death, but daily and hourly in the work and the struggle of many years. She was the sword, the flame of revolution." (48)

In January, 1919 the Spartacus League changed its name to the German Communist Party (KPD). Later that year she switched from the USPD to the KPD. Other members included Paul Levi, Willie Munzenberg, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Julian Marchlewski, Ernst Thälmann, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Franz Mehring, and Ernest Meyer. Levi's moderate approach to communism increased the size of the party and in the 1924 elections they won 62 seats in the Reichstag. (49)

Clara Zetkin served on the Central Committee of the KPD. She was also appointed to the executive committee of Comintern which meant she spent long period in the Soviet Union. A life-long anti-racist, Zetkin took part in the international protests against Jim Crow laws in the United States. She also campaigned against the conviction of the Scotsboro Boys.

In March, 1929, Clara Zetkin wrote to Nikolai Bukharin complaining about the way the KPD was being run. "I feel completely alone and alien in this body, which has changed from being a living political organism into a dead mechanism, which on one side swallows orders in the Russian language and on the other spits them out in various languages, a mechanism which turns the mighty world historical meaning and content of the Russian revolution into the rules of the game for Pickwick Clubs." (50)

In 1932, Zetkin, although seventy-five years old, was once again elected to the Reichstag. As the oldest member she was entitled to open the parliament's first session. Zetkin took the opportunity to make a long speech where she denounced the policies of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. "Motivated by imperialist cravings, they bring Germany into aimless, amateurish vacillations between clumsily currying favour with and sabre-rattling against the Great Powers of the Versailles Treaty, which will bring this country into greater dependence upon them. They also damage relations with the Soviet Union - the state that, through its honest policies of peace and its economic ascendance, stands behind the German working population."

Zetkin condemned the terror tactics employed during the election campaign. "The presidential cabinet bears a great burden of guilt. It is fully responsible for the murders of the last few weeks, murders for which it is fully responsible through its abolishing the ban on uniforms for the National Socialist Storm Troopers and by its open patronage of Fascist civil-war troops. In vain, it seeks to hide its political and moral guilt through quarrels with its allies about the division of power in the state; the blood that has been spilled will forever link it to the Fascist murders." (51)

Clara Zetkin died on 20th June, 1933.

Primary Sources

(1) Clara Zetkin, speech at the International Workers' Congress in Paris (19th July, 1889)

What made women's labour particularly attractive to the capitalists was not only its lower price but also the greater submissiveness of women. The capitalists speculate on the two following factors: the female worker must be paid as poorly as possible and the competition of female labour must be employed to lower the wages of male workers as much as possible. In the same manner the capitalists use child labour to depress women's wages and the work of machines to depress all human labour.

(2) Clara Zetkin, Die Gleichheit (1st November, 1893)

It is not just the women workers who suffer because of the miserable payment of their labour. The male workers, too, suffer because of it. As a consequence of their low wages, the women are transformed from mere competitors into unfair competitors who push down the wages of men. Cheap women's labour eliminates the work of men and if the men want to continue to earn their daily bread, they must put up with low wages. Thus women's work is not only a cheap form of labour, it also cheapens the work of men and for that reason it is doubly appreciated by the capitalist, who craves profits.

Given the fact that many thousands of female workers are active in history, it is vital for the trade unions to incorporate them into their movement. In individual industries where female labour pays an important role, any movement advocating better wages, shorter working hours, etc., would not be doomed from the start because of the attitude of those women workers who are not organized.

(3) Clara Zetkin, speech at the Second International in Copenhagen (1907)

The socialist parties of all countries are duty bound to fight energetically for the implementation of universal women's suffrage which is to be vigorously advocated both by agitation and by parliamentary means. When a battle for suffrage is conducted, it should only be conducted according to socialist principles, and therefore with the demand of universal suffrage for women and men.

(4) Clara Zetkin, letter to Helen Ankersmit (7th September , 1913)

If the women of the people are to be won for socialism then we need in part special ways, means and methods. If those who are awakened are to be schooled for work and struggle in the service of socialism theoretically and practically, then we must have special organisations and arrangements for it. This is explained by the historical milieu of proletarian women, by the specific psychological character of women, which has become historical, and finally by the multitude of duties which burden the proletarian woman, in a word by all the actual living conditions which economically, politically, socially and spiritually create a certain special position for women. Certainly many proletarian women will awake even without special social women’s agitation in spite of all these conditions. Certainly also many awakened women will be drawn into the general movement through joint work without special organisations for theoretical and practical schooling. But we must not forget that these are an elite who are above the average. What is important however is to seize and hold the broadest masses of proletarian women. Therefore we must tailor our measures for agitation and education not for the elite but for the average. But – as stated – we will not manage without special measures whose driving and executive forces are predominantly women who are dedicated to the awakening and education of women.

(5) Clara Zetkin, Die Gleichheit (7th November, 1914)

When the men kill, it is up to us women to fight for the preservation of life. When the men are silent, it is our duty to raise our voices in behalf of our ideals.

(6) Clara Zetkin, letter to Helen Ankersmit (3rd December, 1914)

The most disastrous phenomenon of the current situation is the factor that imperialism is employing for its own ends all the powers of the proletariat, all of its institutions and weapons, which its fighting vanguard has created for its war of liberation. Social Democracy bears the main guilt and responsibility for this phenomenon before the International and history. The granting of the war credits was the harbinger for the equally comprehensive and revolting process of capitulation of German Social Democracy.

The majority nowadays no longer constitutes a proletarian Socialist party of class battles, but a nationalist social reforming party which waxes enthusiastic over annexations and conquests of colonies. Social Democratic and trade union organs have approved of the illegal invasion of Belgium, of the massacre of suspected guerrillas, as well as their wives and children, as well as the destruction of their homes in various towns and districts.

(7) Clara Zetkin, speech at the International Women's Peace Conference (15th March, 1915)

Who profits from this war? Only a tiny minority in each nation: The manufacturers of rifles and cannons, of armor-plate and torpedo boats, the shipyard owners and the suppliers of the armed forces' needs. In the interests of their profits, they have fanned the hatred among the people, this contributing to the outbreak of the war. The workers have nothing to gain from this war, but they stand to lose everything that is dear to them.

(8) Clara Zetkin, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Fight Against the German Betrayers of International Socialism (May, 1919)

In Rosa Luxemburg the socialist idea was a dominating and powerful passion of both mind and heart, a consuming and creative passion. To prepare for the revolution, to pave the way for socialism - this was the task and the one great ambition of this exceptional woman. To experience the revolution, to fight in its battles - this was her highest happiness. With will-power, selflessness and devotion, for which words are too weak, she engaged her whole being and everything she had to offer for socialism. She sacrificed herself to the cause, not only in her death, but daily and hourly in the work and the struggle of many years. She was the sword, the flame of revolution.

(8) Clara Zetkin, speech in the Reichstag (30th August, 1932)

At present, those in power in Germany have seized hold of a presidential cabinet which was formed by the side-lining of the Reichstag and which is the henchman of trustified monopoly capital and the large landowners. Its driving force is the Reichswehr generals.

In spite of its omnipotence, the presidential cabinet has proved a miserable failure in the face of all the political tasks of the hour - both at home and abroad. Just like the previous cabinet, its domestic policies are characterized by the emergency decrees, which are emergency decrees in the most literal sense of the word; for these laws decree emergency and intensify the already existing emergency. At the same time, this cabinet tramples upon the rights of the masses to struggle against the emergency. The only people this government sees as needing and eligible for help are indebted large landowners, bankrupt industrialists, giant banks, shipowners and unscrupulous speculators and racketeers. Its taxation, tariff and trade policies hit broad layers of the working people in order to benefit small interest groups and to exacerbate the crisis by further restricting consumption, imports and exports.

Equally, its foreign policies are a slap in the face of the interests of the working people. Motivated by imperialist cravings, they bring Germany into aimless, amateurish vacillations between clumsily currying favour with and sabre-rattling against the Great Powers of the Versailles Treaty, which will bring this country into greater dependence upon them. They also damage relations with the Soviet Union - the state that, through its honest policies of peace and its economic ascendance, stands behind the German working population.

The presidential cabinet bears a great burden of guilt. It is fully responsible for the murders of the last few weeks, murders for which it is fully responsible through its abolishing the ban on uniforms for the National Socialist Storm Troopers and by its open patronage of Fascist civil-war troops.

In vain, it seeks to hide its political and moral guilt through quarrels with its allies about the division of power in the state; the blood that has been spilled will forever link it to the Fascist murders.

The impotence of the Reichstag and the omnipotence of the presidential cabinet are an expression of the decay of bourgeois liberalism, which inevitably accompanies the collapse of the capitalist mode of production. This decline also fully impacts on reformist Social Democracy, which bases itself in theory and practice on the rotten soil of the bourgeois social order.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Who Set Fire to the Reichstag? (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)