Scottsboro Boys

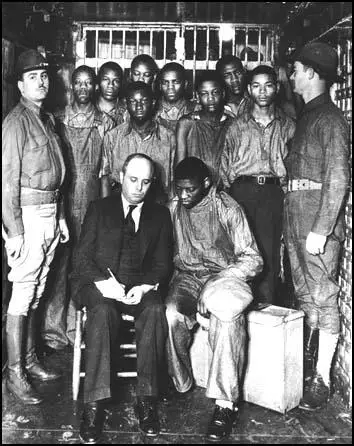

On 25th March, 1931, Victoria Price (21) and Ruby Bates (17) claimed they were gang-raped by 12 black men on a Memphis bound train. Nine black youths on the train were arrested and charged with the crime. Twelve days later the trial of Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems, Clarence Norris, Andy Wright, Ozzie Powell, Olen Montgomery, Eugene Williams and Willie Roberson took place at Scottsboro, Alabama. Their defence attorney was an alcoholic, who was drunk throughout the trial. The prosecutor on the other hand, told the jury, "Guilty or not, let's get rid of these niggers". After three days all nine men were found guilty: eight, including two aged 14, were sentenced to death and the youngest man, who was only thirteen, was given life imprisonment.

John Gates later wrote: "A few weeks after I joined the YCL (Young Communist League), nine young Negroes were arrested on a freight train near Scottsboro, Alabama, convicted of raping two white women and sentenced to the electric chair. This was the famous Scottsboro case. It was to have lasting significance for our country and to set off a chain reaction that is still felt throughout the world.... The plight of an entire people was suddenly illumined for me. Besides, some of the Scottsboro Boys themselves were of my own age; they were victims of the same depression which affected all of us in one way or another. The role of the Communists in the case confirmed my conviction that I had been right in joining up with them."

Two famous writers, Theodore Dreiser and Lincoln Steffens, publicized the case by writing articles on how the men had been falsely convicted. The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and the American Communist Party both became involved in the campaign and Clarence Darrow, America's leading criminal lawyer, took up the case. In November, 1932, the United States Supreme Court ordered a second trial on the grounds that the men had been inadequately defended in court.

Although Ruby Bates testified at the second trial that the rape story had been invented by Victoria Price and the crime had not taken place, the men were once again found guilty. Mary Heaton Vorse wrote: "The Scottsboro case is not simply one of race hatred. It arose from the life that was followed by both accusers and accused, girls and boys, white and black. If it was intolerance and race prejudice which convicted Haywood Patterson, it was poverty and ignorance which wrongfully accused him."

Heywood Broun, probably the most popular journalist in the United States at the time, took up the case. He also wrote about the conviction of the innocent Tom Mooney. However, in 1933 he was expelled from the Socialist Party of America after appearing with members of the Communist Party at a rally demanding the release of these men. Broun wrote in the New York World-Telegram on 29th April 1933: "I don't expect the Communists to love me, and I'm not going to love them. I hope from time to time to say many things about them, and I expect the same in return. But I think it would be a fine idea not to fight until Tom Mooney is free and the Scottsboro boys are acquitted."

A third trial ended with the same result but a fourth in January, 1936, resulted in four of the men being acquitted. Lincoln Steffens, like many other journalists, continued with his campaign. "No state in this union has a right to speak of justice as long as the most friendless Negro child accused of a crime receives less than the best defence that would be given its wealthiest white citizen."

Richard B. Moore, was another civil rights activist who campaigned for the men's release. In 1940 he argued: "The Scottsboro Case is one of the historic landmarks in the struggle of the American people and of the progressive forces throughout the world for justice, civil rights and democracy. In the present period, the Scottsboro Case has represented a pivotal point around which labor and progressive forces have rallied not only to save the lives of nine boys who were framed... but also against the whole system of lynching terror and the special oppression and persecution of the Negro people... Last year we came to a new development in the Scottsboro Case which shows more clearly than ever before the fascist nature of this case. Governor Graves (of Alabama) gave his pledged word to the Scottsboro Defense Committee and to leading Alabama citizens at a hearing to release the remaining Scottsboro boys." Four more of the men were released in the 1940s but the last prisoner, Andy Wright, had to wait until 9th June, 1950, before achieving his freedom. This was nineteen years and two months after his arrest in Alabama.

The nine men were finally pardoned in October, 1976. Only one of the men, Clarence Norris, who had spent 15 years in prison for the crime, was still alive. He commented when he heard the news: "I only wish the other eight boys could be here today. Their lives were ruined by this thing, too." In April 1977 the Alabama House Judiciary Committee rejected a proposal to pay Norris $10,000 in compensation for his time spent in prison. The last of the group, Clarence Norris, died in 1989.

On 20th November, 2013, Alabama’s parole board granted posthumous pardons for the three remaining members of the group who had yet to have their convictions rescinded, Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems and Andy Wright. Sheila Washington, a Scottsboro resident who has led the campaign to pardon the men, told The Guardian that holding the three pardon certificates in her hand had been “joyous and sad at the same time. I feel like jumping up and down and rejoicing for them, because this is something they wanted in their lifetimes but it never happened.”

Primary Sources

(1) On May, 1931, Lincoln Steffens , Theodore Dreiser and a group of writers sent an open letter to the Governor Miller of Alabama.

No state in this union has a right to speak of justice as long as the most friendless Negro child accused of a crime receives less than the best defence that would be given its wealthiest white citizen.

(2) In April, 1933, Heywood Broun was expelled from the Socialist Party for sharing the lecture platform with members of the Communist Party during a rally demanding the release of Tom Mooney and the Scottsboro Nine. He wrote about the event in the New York World-Telegram (29th April, 1933)

I don't expect the Communists to love me, and I'm not going to love them. I hope from time to time to say many things about them, and I expect the same in return. But I think it would be a fine idea not to fight until Tom Monney is free and the Scottsboro boys are acquitted.

(3) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

A few weeks after I joined the YCL (Young Communist League), nine young Negroes were arrested on a freight train near Scottsboro, Alabama, convicted of raping two white women and sentenced to the electric chair. This was the famous Scottsboro case. It was to have lasting significance for our country and to set off a chain reaction that is still felt throughout the world.

The Daily Worker gave banner headlines to the case - this was April, 1931 - and the Communist Party rose to the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, as they were called. The Communists charged that the case was a frame-up from start to finish, and, in fact, that is just what it turned out to be. The fight proved to be a prolonged and stormy one. Nothing had so dramatized the issue of civil rights since the Civil War. Finally all the boys were freed, but only after years of national and world protest-campaigns and protracted legal battles, and after the white women in the case confessed to having lied, one of the women, Ruby Bates, even joining the crusade for the freedom of the young Negroes.

Before the case reached its final conclusion, a large part of America was made aware for the first time of the code under which southern Negroes enjoyed no rights, could expect no justice.

The Communists took the initiative in the case, although in later stages the legal defense was taken over by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and others, and lawyers like Samuel Leibowitz played a prominent role. It has been charged that the Communists cared less about defending the boys than about dramatizing the larger political issues, but this argument has never impressed me.

The Scottsboro frame-up was the product of an outrageous social and legal system in the South (still existing in large part); individual cases could not be separated from the oppressive background which gave rise to them. The Communists deserve credit not only for pioneering in the case, but for focusing the attention of the country on the underlying issues. This campaign opened the way for an assault upon the all-white jury system and the white primary. The trouble has not been that the Communists ever did too much but that white America has done too little, and this is our national shame.

I myself was deeply moved by the terrible injustice that the case revealed. The plight of an entire people was suddenly illumined for me. Besides, some of the Scottsboro Boys themselves were of my own age; they were victims of the same depression which affected all of us in one way or another. The role of the Communists in the case confirmed my conviction that I had been right in joining up with them.

(4) Mary Heaton Vorse, How Scottsboro Happened, New Republic (10th May, 1933)

Out of the contradictory testimony of the trial, the Scottsboro story finally emerged. It unwound itself slowly, tortuously. As witnesses for the prosecution and the defense succeeded one another, they revealed what took place on the southbound freight between Chattanooga and Huntsville, and how they happened to be riding on it, and how they lived at home and in the hobo jungles. It was a murky story of degradation and horror that rivals anything written by Faulkner.

The Scottsboro case is not simply one of race hatred. It arose from the life that was followed by both accusers and accused, girls and boys, white and black. If it was intolerance and race prejudice which convicted Haywood Patterson, it was poverty and ignorance which wrongfully accused him.

Victoria Price was spawned by the unspeakable conditions of Huntsville. These medium-sized mill towns breed a sordid viciousness which makes gangsters seem as benign as Robin Hood and the East Side a cultural paradise. As you leave Huntsville you pass through a muddle of mean shacks on brick posts standing in garbage-littered yards. They are dreary and without hope. No one has planted a bit of garden anywhere.

Victoria Price grew up here, worked in the mill for long hours at miserable wages, and here was arrested for vagrancy, for violation of the Volstead Act, and served a sentence in the workhouse on a charge of adultery. Here she developed the callousness which made it possible for her to accuse nine innocent boys. In jail in Scottsboro she quarreled with the boy who remained on the train, Orval Gilley, alias Carolina Slim, and with Lester Carter, the Knoxville Kid, because they refused to testify with her. Orval Gilley said he would "burn in torment" if he testified against innocent boys, but Victoria, the product of the mean mill-town streets, said she "didn’t care if every nigger in Alabama was stuck in jail forever."

The chief actors in the trial besides Haywood Patterson, the trial’s dark core, were the three hobo children: Victoria Price of the hard face; Ruby Bates, the surprise witness who recanted her former testimony and insisted that she had accused the boys in the first place because ""Victoria had told her to"; and Lester Carter, the girls’ companion in the "jungle."

On both Ruby Bates and Lester Carter, the jury smelled the North where they had been. Carter offended them by his gestures, by the fact that he said "Negro" - showing "subversive Northern influences." Ruby Bates was dressed in a neat, cheap gray dress and a little gray hat; Lester Carter had on a cheap suit of clothes. Their clothes probably threw their testimony out of court for the jury. The jury, as well as most people in the courtroom, believed these clothes were "bought with Jew money from New York."

Ruby Bates, Victoria Price and Lester Carter among them gave a picture of the depths of our society. They told how the hobo children live, of their innocent depravity, of their promiscuous and public lovemaking.

Lester Carter, just off the chain gang for pilfering laundry, was taken to Victoria Price’s house by Jack Tiller, the "boy friend" for whom she had been serving time in the workhouse. Carter was staying at the Tillers’. There would be words between Tiller and his wife, and Tiller would go over to Victoria’s. It is interesting to note that Tiller was in the witness room during the trial, but was never put on the stand.

In the Prices’ front room there was a bed; behind that was a kitchen room, and a shed, and a yard behind that. Victoria’s mother and Carter talked together. Tiller and Victoria sat on the bed. Later they went out. The next night Victoria introduced Ruby Bates to Lester Carter, and the four of them went off to a hobo jungle. "We all sat down near a bendin’ lake of water where they was honeysuckles and a little ditch. I hung my hat up on a little limb—" And here in each other’s presence they all made love.

"Did you see Jack Tiller and Victoria Price?" Lester Carter was asked.

"Sure. They would scoot down on top of us. They was on higher ground." All four of them were laughing at this promiscuous lovemaking. It began to rain, so they went to a box car in the railroad yards. Here they spent the night together and made plans to go West and "hustle the towns." The girls both had on overalls, Victoria’s worn over her three dresses; both had coats, probably their entire wardrobe. The girls were already what Judge Horton had called them in his charge to the jury: "women of the underworld," whose amusements were their promiscuous love affairs, whose playgrounds were hobo swamps and the unfailing freight cars.

Why not? What was to stop them? What did Huntsville or Alabama or the United States offer a girl for virtue and probity and industry? A mean shack, many children for whom there would not be enough food or clothing or the smaller decencies of life, for whom, at best there would be long hours in the mill—and, as now, not even the certainty of work.

With hunger, dirt, sordidness, the reward of virtue, why not try the open road, the excitement of new places? One could always be sure of a boy friend, a Chattanooga Chicken or a Knoxville Kid or a Carolina Slim, to be a companion in the jungle and to go out "a-bummin’" for food. More fun for the girls to "hustle the towns" than to stay in Huntsville in a dirty shack, alternating long hours in the mill with no work at all. Ruby Bates’s mother had had nine children. What had Ruby ever seen in life that rewarded virtue with anything but work and insecurity?

In the cozy box car they went on with their exciting plans. Jack Tiller said he had better not go with the girls on account of the Mann Act and the conviction already on record between him and Victoria. He could join them later. So the two girls and the Knoxville Kid went on to Chattanooga together, bumming their way.

Victoria Price had said on the witness stand that when they got to Chattanooga they went to "Callie Broochie’s" boarding house, "a two-story white house on Seventh Street," and had looked for work. In reality they had stayed all night in the hobo jungle, where they picked up Orval Gilley, alias Carolina Slim, another of the great band of wandering children, another of those for whom this civilization had no place. Here the boys made a "little shelter from boughs" for the girls and went off to "stem" for food. Nellie Booth’s chili cart gave them some, and "tin cans in which to heat coffee." Many different witnesses saw them there in the hobo swamp in the morning. The quartet boarded the freight car which was to make so much dark history. They found five other white boys on the train. Scattered the length of the freight car were Negro boys.

Among these were four very young boys, Negroes from Chattanooga, Andy and Roy Wright, Haywood Patterson and another boy of fourteen. One of the Wright boys was thirteen. These little Negro-boy hoboes stayed by themselves on an oil-tank car. White tramps came past and "tromped their hands."

"Look out, white boy," Haywood Patterson warned. "Yo’ll make me fall off !"

"That’d be too bad !" said the white boy. "There’d be one nigger less !" Then the white boys got off the train as it was going slow, and "chunked" the Negro boys with rocks.

There is one precious superiority which every white person has in the South. No matter how low he has fallen, how degraded he may be, he still can feel above the "niggers." It was this feeling of superiority that started the fight between the white hobo boys and the black hoboes on the train between Chattanooga and Hunstville.

It started because seven white-boy bums were above riding even on the same train with Negroes. The Negroes decided to rush the white boys. The four very young Negroes were asked to come along by the older boys. The dozen Negroes on the train fought the seven white boys, and put them off the train.

The only decent moment in the whole story was the dragging back of Orval Gilley - Carolina Slim - by one of the Negro boys, apparently Haywood Patterson. He had pulled the white boy Gilley back on the train by his belt, perhaps saving his life. When asked on the witness stand if he had committed the crime, Haywood Patterson cried in a loud voice—

"Do yo’ think I’d ’a pulled a white boy back to be a witness if I’d ben a-fixin’ to rape any white woman ?"

Gilley then climbed in the gondola with the girls, a "churt car" full of finely crushed rock for mending the road bed. It was in this car that the conductor later found Victoria’s snuff box. The four young Negro boys from Chattanooga went back to their former places and sat facing each other. The white boys who had been put off the train complained to the authorities at Stevenson, who telephoned ahead.

At Paint Rock a posse of seventy-five men arrested the nine Negroes in different places on the train. The girls in overalls, fearing a vagrancy charge, then accused the Negro boys of assault.

Ruby Bates, Victoria Price and their companions, Orval Gilley and Lester Carter, were all taken to the jail together. The rest of the story is known.

Observe that this quartet of young people has no standards, no training, no chance of advancement; that there is for them not even the promise of low-paid steady employment. They have one thing only—the trains going somewhere, the box cars for homes, the jungles for parks. They pilfer laundry, clothes, as a matter of course. They bum their food, the girls "pick up a little change hustling the towns," and it’s all a lot better than the crowded shacks at home and the uncertain work in the mills.

Apparently Victoria had come in and out of Chattanooga often. Lewis, a Negro who lived near the jungle, the one whose "sick wheezin’ hawg" wandered in and out of the story, testified that Victoria had often begged food "off his old woman." Victoria Price and Ruby Bates are no isolated phenomenon. The children’s bureau reports 200,000 children under twenty-one wandering through the land. These two girls are part of a great army of adventurous, venal girls who like this way of life.

For it is a way of life, something that from the bottom is rotting out our society. Boys and girls are squeezed out of the possibility of making a living, they are given nothing else; but there are the shining rails and trains moving somewhere, so the road claims them. The girls semi-prostitutes, the boys sometimes living on the girls, and all of them stealing and bumming to end up with a joyous night in a box car.

The fireman on the freight train was asked what he thought when he saw the girls on the train. He answered "he didn’t think a thing of it, he saw so many white girls nowadays a-bummin’ on trains." Victoria Price is only one of thousands who put overalls on over all the clothes they own and hit the road; only one of thousands, one who has had all kindness and decency ground out of her in her youth.

(5) William Patterson, The Man Who Cried Genocide (1971)

It had begun March 25, 1931, when nine Negro lads were dragged by a sheriff and his deputies from a 47-car freight train that was passing through Paint Rock, Alabama, on its way to Memphis. The train was crowded with youths, both white and Black, aimlessly wandering about. They were riding the freights in search of food and employment and they wandered about aimlessly in the train. There was a fight, and some white lads telegraphed ahead that they had been jumped and thrown off the train by "niggers." At Paint Rock, a sheriff and his armed posse boarded the train and began their search for the "niggers."

Two white girls dressed in overalls were taken out of a car; white and Black youths alike were arrested and charged with vagrancy. But the presence of the white girls added a new dimension to the arrest. The girls were first taken to the office of Dr. R. R. Bridges for physical examination. No bruises were found on their bodies, no were they unduly nervous. A small amount of semen was found in the vagina of each of them but it was at least a day old.

The doctor gave his report to the sheriff and obviously it ruled out rape in the preceding 24 hours. But for the Alabama authorities that made no difference - they came up with a full-blown charge of rape. The nine Black lads stood accused.

The second day after the arrests the sheriff tried to get the girls to say they had been raped by the youths, and both refused. They were sent back to jail, but a Southern sheriff can exert a lot of pressure, and on the following day Victoria Price, the older of the two women (who had a police record), caved in. Ruby Bates, the 17-year-old, an almost illiterate mill hand, still refused to corroborate the charge. But on the fourth day she, too, succumbed to the pressure. The Roman holiday could now be staged.

On March 31, 1931, 20 indictments were handed down by a grand jury, emphasizing the charge of rape and assault. The nine boys were immediately arraigned before the court in Scottsboro. All pleaded not guilty.

The first exposure of the infamous frame-up appeared April 2, 1931, in the pages of the Daily Worker, which called on the people to initiate mass protests and demonstrations to save nine innocent Black youths from legal lynching. On April 4, the Southern Worker, published in Chattanooga, Tenn., carried a first-hand report from Scottsboro by Helen Marcy describing the lynch spirit that had been aroused around the case. The trail began on April 7 - with the outcome a foregone conclusion.

Thousands of people poured into Scottsboro - if there were "niggers" to be lynched, they wanted to see the show. A local brass band played "There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight" outside the courthouse while the all-white jury was being picked. The state militia was called out - ostensibly to protect the prisoners. Its attitude toward the lads, one of whom was bayonetted by a guardsman, was little different from that of the lynch mob. In short order, Charles Weems, 20, and Clarence Norris, 19, the two older lads, were declared guilty by the jury. On the same day, Haywood Patterson, 17, was the next victim. And on April 8, Ozie Powell, 14; Eugene Williams, 13; Olin Montgomery, 17; Andy Wright, 18; and Willie Robertson, 17, were declared guilty. The hearing of Roy Wright, 14 years old, ran into "legal" difficulties. The prosecution had asked the jury to give him life imprisonment, but eleven jurors voted for death, and it was declared a mistrial.

(6) Richard B. Moore, speech at the National Conference of the International Labor Defense (1940)

The Scottsboro Case is one of the historic landmarks in the struggle of the American people and of the progressive forces throughout the world for justice, civil rights and democracy. In the present period, the Scottsboro Case has represented a pivotal point around which labor and progressive forces have rallied not only to save the lives of nine boys who were framed... but also against the whole system of lynching terror and the special oppression and persecution of the Negro people...

Last year we came to a new development in the Scottsboro Case which shows more clearly than ever before the fascist nature of this case. Governor Graves (of Alabama) gave his pledged word to the Scottsboro Defense Committee and to leading Alabama citizens at a hearing to release the remaining Scottsboro boys.

(7) Henry Lee Moon, Balance of Power (1948)

It was during this period, in the spring of 1931, that nine colored lads, in age from thirteen to nineteen years, were arrested in Alabama and charged with the rape of two nondescript white girls. The defense of these boys was first undertaken by the NAACP. But the Communists, through the International Labor Defense, captured the defense of the imprisoned youths and conducted a vigorous, leather-lunged campaign that echoed and reechoed throughout the world. The Scottsboro boys were lifted from obscurity to a place among the immortals - with Mooney and Billings, Sacco and Vanzetti - fellow-victims of bias in American courts.

(8) Jessica Mitford, A Fine Old Conflict (1977)

I had an ally in William L. Patterson, who often came out from New York on a national tour to meet with CRC chapters around the country. Pat, then in his late fifties, was a formidable figure in the black Party leadership. The son of a slave, he was a practising lawyer at the time of the Sacco and Vanzetti case which had led him into the Party. As a leader in the International Labour Defense he had organized the mass defence of the Scottsboro Boys in the thirties. Although Pat operated on a national and international level - one of his many dazzling achievements was presentation of the CRC petition, 'We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People,' at a United Nations meeting in Paris - he always had time for the lower-echelon CRC workers, and took a deep interest in the day-to-day organizational problems that beset us.

(9) Ed Pilkington, The Guardian (21st November, 2013)

Eighty-two years and eight months after they were arrested and framed for raping two white women on board a freight train heading to Memphis, justice has finally been served for all of the Scottsboro Nine, though none are alive to enjoy the bittersweet moment.

Alabama’s parole board granted posthumous pardons on Thursday for the three remaining members of the group who had yet to have their convictions rescinded – finally laying to rest one of the great miscarriages of the civil rights era. The pardons were issued for Haywood Patterson, Charlie Weems and Andy Wright, all of whom were initially sentenced to death and who served long prison sentences having been found guilty by all-white juries on trumped-up charges.

The nine deceased African Americans were represented at the parole board meeting, in the absence of any family members, by Sheila Washington, a Scottsboro resident who has led the campaign to pardon the men. The last of the group, Clarence Norris, died in 1989.

Washington told the Guardian that holding the three pardon certificates in her hand had been “joyous and sad at the same time. I feel like jumping up and down and rejoicing for them, because this is something they wanted in their lifetimes but it never happened.”

The certificates will next month be placed in pride of place at the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center that Washington founded in a disused church near the centre of town. “Although they won’t be here to see it, the story of the nine will now be told – that all of them have finally been declared innocent.”

The nine boys entered into an altercation with some white youths as they were on the freight train passing through Alabama, on the night of 25 March 1931. When the train stopped at Scottsboro a posse of local white men boarded the train and took the teenagers captive; they also found two white women on board, who said they had been raped.

Although one of the women recanted her story in court, the nine were still sentenced to death by all-white juries. The case was to have enduring legal ramifications – the US supreme court ruled on the back of it that black people could not be excluded from juries on racial grounds.

Five of the accused teenagers – Olen Montgomery, Ozie Powell, Willie Roberson, Eugene Williams and Roy Wright – had their convictions overturned on appeal. In 1976, Norris became the only Scottsboro Boy to be pardoned while alive. That left three with convictions still on the books – until Thursday morning.

To clear the way for the pardons, the Alabama legislature had to introduce a new law allowing posthumous pardons, honed specifically to this case. Arthur Orr, a Republican state senator who sponsored the rule change, told the parole board: “Today is a reminder that it is never too late to right a wrong. We cannot go back in time and change the course of history, but we can change how we respond.”