National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

On 14th August, 1908, William English Walling and Anna Strunsky heard about the Springfield Riot in Illinois, where a white mob attacked local African Americans. During the riot two were lynched, six killed, and over 2,000 African Americans were forced to leave the city. Walling and Strunsky decided to visit Springfield "to write a broad, sympathetic and non-partizan account". When they arrived they interviewed Kate Howard, one of the leaders of the riots. Walling later wrote: "We at once discovered, to our amazement, that Springfield had no shame." He and Anna were treated to "all the opinions that pervade the South - that the negro does not need much education, that his present education even has been a mistake, that whites cannot live in the same community with negroes except where the latter have been taught their inferiority, that lynching is the only way to teach them, etc."

On 3rd September 1908, Walling published his article, Race War in the North. Walling complained that "a large part of the white population" in the area were waging "permanent warfare with the Negro race". He quoted a local newspaper as saying: "It was not the fact of the whites' hatred toward the negroes, but of the negroes' own misconduct, general inferiority or unfitness for free institutions that were at fault." Walling argued that they only way to reduce this conflict was "to treat the Negro on a plane of absolute political and social equality".

Walling argued that the people behind the riots were seeking economic benefits: "If the white laborers get the Negro laborers' jobs; if masters of Negro servants are able to keep them under the discipline of terror as I saw them doing in Springfield; if white shopkeepers and saloon keepers get their colored rivals' trade; if the farmers of neighboring towns establish permanently their right to drive poor people out of their community, instead of offering them reasonable alms; if white miners can force their negro fellow-workers out and get their positions by closing the mines, then every community indulging in an outburst of race hatred will be assured of a great and certain financial reward, and all the lies, ignorance and brutality on which race hatred is based will spread over the land."

Walling suggested that racists were in danger of destroying democracy in the United States: "The day these methods become general in the North every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as in the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war, which shall obliterate not only the remains of slavery but all other obstacles to a free democratic evolution that have grown up in its wake. Yet who realizes the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid.

Mary White Ovington was a social worker who in 1904 had written a study on racial discrimination, Half a Man: The Status of the Negro. In September 1908, Ovington, was working for the New York Post. Ovington responded to the article by writing to Walling and inviting him and a few friends to her apartment on West Thirty-Eighth Street. Ovington was impressed with Walling: "It always seemed to me that William English Walling looked like a Kentuckian, tall, slender; and though he might be talking the most radical socialism, he talked it with the air of an aristocrat."

Also at the meeting was Charles Edward Russell. He argued: "Wittingly or unwittingly, the entire South was virtually a unit in support of hatred and the ethics of the jungle. The Civil War raged there still, with hardly abated passions. The North was utterly indifferent where it was not covertly or sneakingly applausive of helotry... The whole of the society from which Walling emerged was crystallized against the black man; to view the darker tinted American as a human being was not good form; to insist upon his rights was insufferable gaucherie."

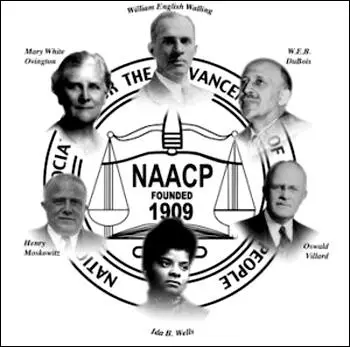

They decided to form the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). The first meeting of the NAACP was held on 12th February, 1909. Early members included William English Walling, Anna Strunsky, Mary Ovington, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Lillian Wald, Florence Kelley, Mary Church Terrell, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, George Henry White, William Du Bois, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, William Dean Howells, Fanny Garrison Villard, Oswald Garrison Villard, Ida Wells-Barnett, Sophonisba Breckinridge, John Haynes Holmes, Mary McLeod Bethune and George Henry White.

The NAACP started its own magazine, Crisis in November, 1910. The magazine was edited by William Du Bois and contributors to the first issue included Oswald Garrison Villard and Charles Edward Russell. The magazine soon built up a large readership amongst black people and white sympathizers. By 1919 Crisis was selling 100,000 copies a month.

In 1915 the NAACP campaigned against the film Birth of a Nation (1915). The film's portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan and African Americans, resulted in the director, D.W. Griffith, being accused of racism. Despite attempts by the NAACP to have the film banned, it was highly successful at the box office.

Mary White Ovington was the first executive secretary of the NAACP. She was replaced by the writer and diplomat, James Weldon Johnson in May, 1917. His assistant was Walter Francis White, and together they managed to rapidly increase the size of the organization. In 1918 the NAACP had 165 branches and 43,994 members.

The NAACP also fought for women's suffrage. Several women, including Mary White Ovington, Jane Addams, Inez Milholland, Josephine Ruffin, Mary McLeod Bethune, Mary Talbert, Mary Church Terrell and Ida Wells-Barnett, were active in both the struggle for women's rights as well as equal civil rights.

The NAACP was also involved in legal battles against segregation and racial discrimination in housing, education, employment, voting and transportation. The NAACP appealed to the Supreme Court to rule that several laws passed by southern states were unconstitutional and won three important judgments between 1915-23 concerning voting rights and housing.

The NAACP also fought a long campaign against lynching. In 1919 it published Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States: 1889-1918. The NAACP also paid for large adverts in major newspapers presenting the facts about lynching. To show that the members of the organization would not be intimidated, it held its 1920 annual conference in Atlanta, considered at the time to be one of the most active Ku Klux Klan areas in America.

In 1929 Walter Francis White became executive secretary of the NAACP. White was an outstanding propagandist and articles that he wrote about African American civil rights appeared in a variety of journals including Collier's, Saturday Evening Post, The Nation, Harper's Magazine and the New Republic. White also wrote a regular column in the New York Herald Tribune and the Chicago Defender.

In July, 1935, Walter Francis White recruited Charles Houston, to establish a legal department for the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). The following year Houston appointed Thurgood Marshall as his assistant. Over the next few years Houston and Marshall used the courts to challenge racist laws concerning transport, housing and education.

In 1940 Thurgood Marshall became chief of the NAACP's legal department. Over the next few years Marshall won 29 of the 32 cases that he argued before the Supreme Court. This included cases concerning the exclusion of black voters from primary elections (1944), restrictive covenants in housing (1948) and unequal facilities for students in state universities (1950).

Some members of the NAACP claimed that Walter Francis White had too much power in the organization. In 1950 the NAACP board decided that Roy Wilkins should replace White as the person in charge of all internal matters. White remained the NAACP's official spokesman until his death on 21st March, 1955.

During the 1950s the main tactic of the NAACP was to use the courts to end racial discrimination in the United States. One of the objectives was the end of the system of having separate schools for black and white children in the South. The states of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia and Kentucky all prohibited black and white children from going to the same school.

The NAACP appealed to the Supreme Court in 1952 to rule that school segregation was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court ruled that separate schools were acceptable as long as they were "separate and equal". It was not too difficult for the NAACP to provide information to show that black and white schools in the South were not equal. One study carried out in 1937 revealed that spending on white pupils in the South was $37.87 compared to $13.08 spent on black children.

After looking at information provided by the NAACP the Supreme Court announced in 1954 that separate schools were not equal and ruled that they were therefore unconstitutional. Some states accepted the ruling and began to desegregate. This was especially true of states where small black populations who had found the provision of separate schools extremely expensive.

Several states in the Deep South refused to accept the judgment of the Supreme Court. In September 1957, the governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, used the National Guard to stop black children from attending the local high school in Little Rock. Film of the events at Little Rock was shown throughout the world. This was extremely damaging to the image of the United States.

On 24th September, 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower, went on television and told the American people: "At a time when we face grave situations abroad because of the hatred that communism bears towards a system of government based on human rights, it would be difficult to exaggerate the harm that is being done to the prestige and influence and indeed to the safety of our nation and the world. Our enemies are gloating over this incident and using it everywhere to misrepresent our whole nation. We are portrayed as a violator of those standards which the peoples of the world united to proclaim in the Charter of the United Nations."

After trying for eighteen days to persuade Orval Faubus to obey the ruling of the Supreme Court, Eisenhower decided to send federal troops to Arkansas to ensure that black children could go to Little Rock Central High School. The white population of Little Rock were furious that they were being forced to integrate their school and Faubus described the federal troops as an army of occupation. The nine black students that entered the school suffered physical violence and constant racial abuse. Although under considerable pressure to leave the school they agreed to stay. In doing so, they showed the rest of the country that African Americans were determined to obtain equality.

The NAACP was also involved in the struggle to end segregation on buses and trains. In 1952 segregation on inter-state railways was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. This was followed in 1954 by a similar judgment concerning inter-state buses. However, states in the Deep South continued their own policy of transport segregation. This usually involved whites sitting in the front and African Americans at the back. When the bus was crowded, the rule was that blacks sitting nearest to the front had to give up their seats to any whites that were standing.

African American people who disobeyed the state's transport segregation policies were arrested and fined. On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, a middle-aged tailor's assistant from Montgomery, Alabama, who was tired after a hard day's work, refused to give up her seat to a white man. After her arrest, Martin Luther King, a pastor at the local Baptist Church, helped organize protests against bus segregation. It was decided that black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration.

After the successful outcome of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, its leader, Martin Luther King, wrote Stride Toward Freedom (1958). The book described what happened at Montgomery and explained King's views on non-violence and direct action and was to have a considerable influence on the civil rights movement.

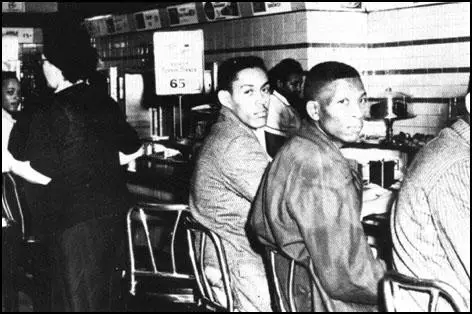

In Greensboro, North Carolina, a small group of black students read the book and decided to take action themselves. They started a student sit-in at the restaurant of their local Woolworth's store which had a policy of not serving black people. In the days that followed they were joined by other black students until they occupied all the seats in the restaurant. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of King they did not hit back.

King's non-violent strategy was adopted by black students all over the Deep South. This included the activities of the Freedom Riders in their campaign against segregated transport. Within six months these sit-ins had ended restaurant and lunch-counter segregation in twenty-six southern cities. Student sit-ins were also successful against segregation in public parks, swimming pools, theaters, churches, libraries, museums and beaches.

Martin Luther King travelled the country making speeches and inspiring people to become involved in the civil rights movement. As well as advocating non-violent student sit-ins, King also urged economic boycotts similar to the one that took place at Montgomery. He argued that as African Americans made up 10% of the population they had considerable economic power. By selective buying, they could reward companies that were sympathetic to the civil rights movement while punishing those who still segregated their workforce.

King also believed in the importance of the ballot. He argued that once all African Americans had the vote they would become an important political force. Although they were a minority, once the vote was organized, they could determine the result of presidential and state elections. This was illustrated by the African American support for John F. Kennedy that helped give him a narrow victory in the 1960 election.

In the Deep South considerable pressure was put on blacks not to vote by organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan. An example of this was the state of Mississippi. By 1960, 42% of the population were black but only 2% were registered to vote. Lynching was still employed as a method of terrorizing the local black population. Emmett Till, a fourteen year old schoolboy was lynched for whistling at a white woman, while others were murdered for encouraging black people to register to vote. King helped organize voting registration campaigns in states such as Mississippi but progress was slow.

During the 1960 presidential election campaign John F. Kennedy argued for a new Civil Rights Act. After the election it was discovered that over 70 per cent of the African American vote went to Kennedy. However, during the first two years of his presidency, Kennedy failed to put forward his promised legislation.

in Greensboro, North Carolina (1963)

The Civil Rights bill was brought before Congress in 1963 and in a speech on television on 11th June, Kennedy pointed out that: "The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day; one third as much chance of completing college; one third as much chance of becoming a professional man; twice as much chance of becoming unemployed; about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year; a life expectancy which is seven years shorter; and the prospects of earning only half as much."

In an attempt to persuade Congress to pass Kennedy's proposed legislation, King and other civil rights leaders organized the famous March on Washington. On 28th August, 1963, more than 200,000 people marched peacefully to the Lincoln Memorial to demand equal justice for all citizens under the law. At the end of the march King made his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

Kennedy's Civil Rights bill was still being debated by Congress when he was assassinated in November, 1963. The new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had a poor record on civil rights issues, took up the cause. Using his considerable influence in Congress, Johnson was able to get the legislation passed.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act made racial discrimination in public places, such as hotels, theaters and restaurants, illegal. It also required employers to provide equal employment opportunities. Projects involving federal funds could now be cut off if there was evidence of discriminated based on colour, race or national origin.

In 1964 the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organised its Freedom Summer campaign. Its main objective was to try an end the political disenfranchisement of African Americans in the Deep South. Volunteers from the three organizations decided to concentrate its efforts in Mississippi. In 1962 only 6.7 per cent of African Americans in the state were registered to vote, the lowest percentage in the country. This involved the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Party (MFDP). Over 80,000 people joined the party and 68 delegates attended the Democratic Party Convention in Atlantic City and challenged the attendance of the all-white Mississippi representation.

The NAACP, CORE and SNCC also established 30 Freedom Schools in towns throughout Mississippi. Volunteers taught in the schools and the curriculum now included black history, the philosophy of the civil rights movement. During the summer of 1964 over 3,000 students attended these schools and the experiment provided a model for future educational programs such as Head Start.

Freedom Schools were often targets of white mobs. So also were the homes of local African Americans involved in the campaign. That summer 30 black homes and 37 black churches were firebombed. Over 80 volunteers were beaten by white mobs or racist police officers and three men, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan on 21st June, 1964. These deaths created nation-wide publicity for the campaign.

The following year, President Lyndon Baines Johnson attempted to persuade Congress to pass his Voting Rights Act. This proposed legislation removed the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes."

Although opposed by politicians from the Deep South, the Voting Rights Act was passed by large majorities in the House of Representatives (333 to 48) and the Senate (77 to 19). The legislation empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list. The following year Lyndon Baines Johnson attempted to persuade Congress to pass his Voting Rights Act. This legislation proposed to remove the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes."

Although opposed by politicians from the Deep South, the Voting Rights Act was passed by large majorities in the House of Representatives (333 to 48) and the Senate (77 to 19). The legislation empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list.

Primary Sources

(1) William English Walling, Race War in the North (3rd September 1908)

If the new Political League succeeds in permanently driving every negro from office; if the white laborers get the Negro laborers' jobs; if masters of negro servants are able to keep them under the discipline of terror as I saw them doing in Springfield; if white shopkeepers and saloon keepers get their colored rivals' trade; if the farmers of neighboring towns establish permanently their right to drive poor people out of their community, instead of offering them reasonable alms; if white miners can force their negro fellow-workers out and get their positions by closing the mines, then every community indulging in an outburst of race hatred will be assured of a great and certain financial reward, and all the lies, ignorance and brutality on which race hatred is based will spread over the land....

Either the spirit of the abolitionists, of Lincoln and of Lovejoy must be revived and we must come to treat the negro on a plane of absolute political and social equality, or Vardaman and Tillman (two of the South's leading spokesmen on race) will soon have transferred the race war to the North....

The day these methods become general in the North every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as in the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war, which shall obliterate not only the remains of slavery but all other obstacles to a free democratic evolution that have grown up in its wake.

Yet who realizes the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid.

(2) Mary White Ovington, The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1914)

In the summer of 1908, the country was shocked by the account of the race riots at Springfield, Illinois. Here, in the home of Abraham Lincoln, a mob containing many of the town's "best citizens," raged for two days, killed and wounded scores of Negroes, and drove thousands from the city. Articles on the subject appeared in newspapers and magazines. Among them was one in the Independent by William English Walling, entitled Race War in the North.

For four years I had been studying the status of the Negro in New York. I had investigated his housing conditions, his health, his opportunities for work. I had spent many months in the South, and at the time of Mr. Walling's article, I was living in a New York Negro tenement on a Negro Street. And my investigations and my surroundings led me to believe with the writer of the article that "the spirit of the abolitionists must be revived."

So I wrote to Mr. Walling, and after some time, for he was in the West, we met in New York in the first week of the year of 1909. With us was Dr. Henry Moskowitz, now prominent in the administration of John Purroy Mitchell, Mayor of New York. It was then that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was born.

It was born in a little room of a New York apartment. It is to be regretted that there are no minutes of the first meeting, for they would make interesting if unparliamentary reading. Mr. Walling had spent some years in Russia where his wife, working in the cause of the revolutionists, had suffered imprisonment; and he expressed his belief that the Negro was treated with greater inhumanity in the United States that the Jew was treated in Russia. As Mr. Walling is a Southerner we listened with conviction. I knew something of the Negro's difficulty in securing decent employment in the North and of the insolent treatment awarded him at Northern hotels and restaurants, and I voiced my protest. Dr. Moskowitz, with his broad knowledge of conditions among New York's helpless immigrants, aided us in properly interpreting our facts. And so we talked and talked voicing our indignation.

(3) National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, statement (12th February, 1909)

The celebration of the Centennial of the birth of Abraham Lincoln, widespread and grateful as it may be, will fail to justify itself if it takes no note of and makes no recognition of the colored men and women for whom the great Emancipator labored to assure freedom. Besides a day of rejoicing, Lincoln's birthday in 1909 should be one of taking stock of the nation's progress since 1865.

How far has it lived up to the obligations imposed upon it by the Emancipation Proclamation? How far has it gone in assuring to each and every citizen, irrespective of color, the equality of opportunity and equality before the law, which underlie our American institutions and are guaranteed by the Constitution?

If Mr. Lincoln could revisit this country in the flesh, he would be disheartened and discouraged. He would learn that on January 1, 1909, Georgia had rounded out a new confederacy by disfranchising the Negro, after the manner of all the other Southern States. He would learn that the Supreme Court of the United States, supposedly a bulwark of American liberties, had refused every opportunity to pass squarely upon this disfranchisement of millions, by laws avowedly discriminatory and openly enforced in such manner that the white men may vote and that black men be without a vote in their government; he would discover, therefore, that taxation without representation is the lot of millions of wealth-producing American citizens, in whose hands rests the economic progress and welfare of an entire section of the country.

He would learn that the Supreme Court, according to the official statement of one of its own judges in the Berea College case, has laid down the principle that if an individual State chooses, it may make it a crime for white and colored persons to frequent the same market place at the same time, or appear in an assemblage of citizens convened to consider questions of a public or political nature in which all citizens, without regard to race, are equally interested.

In many states Lincoln would find justice enforced, it at all, by judges elected by one element in a community to pass upon the liberties and lives of another. He would see the black men and women, for whose freedom a hundred thousand of soldiers gave their lives set apart in trains, in which they pay first-class fares for third-class service, and segregated in railway stations and in places of entertainment; he would observe that State after state declines to do its elementary duty in preparing the Negro through education for the best exercise of citizenship.

(4) Harry S. Truman, speech (29th June, 1947)

We can no longer afford the luxury of a leisurely attack upon prejudice and discrimination. There is much that state and local governments can do in providing positive safeguards for civil rights. But we cannot, any longer, await the growth of a will to action in the slowest state or the most backward community. Our national government must show the way.

(5) Chief Justice Earl Warren, Supreme Court ruling on segregated education (17th May, 1954)

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.

To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.

(6) National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People statement (1955)

All Americans are now relieved to have the law of the land declare in the clearest language: ".. in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." Segregation in public education is now not only unlawful; it is un-American. True Americans are grateful for this decision. Now that the law is made clear, we look to the future. Having canvassed the situation in each of our states, we approach the future with the utmost confidence. . . .

We stand ready to work with other law abiding citizens who are anxious to translate this decision into a program of action to eradicate racial segregation in public education as speedily as possible.

While we recognize that school officials will have certain administrative problems in transferring from a segregated to a nonsegregated system, we will resist the use of any tactics contrived for the sole purpose of delaying desegregation.

We insist that there should be integration at all levels, including the assignment of teacher-personnel on a nondiscriminatory basis.

We look upon this memorable decision not as a victory for Negroes alone, but for the whole American people and as a vindication of America's leadership of the free world.

Lest there be any misunderstanding of our position, we here rededicate ourselves to the removal of all racial segregation in public education and reiterate our determination to achieve this goal without compromise of principle.

(7) President Dwight Eisenhower, television broadcast on Little Rock (24th September, 1957)

At a time when we face grave situations abroad because of the hatred that communism bears towards a system of government based on human rights, it would be difficult to exaggerate the harm that is being done to the prestige and influence and indeed to the safety of our nation and the world. Our enemies are gloating over this incident and using it everywhere to misrepresent our whole nation. We are portrayed as a violator of those standards which the peoples of the world united to proclaim in the Charter of the United Nations.

(8) Martin Luther King, Christian Century Magazine (1957)

Privileged groups rarely give up their privileges without strong resistance. Hence the basic question which confronts the world's oppressed is: How is the struggle against the forces of injustice to be waged? The alternative to violence is non-violent resistance. The non-violent resister must often express his protest through non-cooperation or boycotts, but he realizes that non-cooperation and boycotts are not ends in themselves; they are merely means to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent.

(9) In 1980, Benjamin Hooks, president of the NAACP, explained why the organization was against using violence to obtain civil rights.

There are a lot of ways an oppressed people can rise. One way to rise is to study, to be smarter than your oppressor. The concept of rising against oppression through physical contact is stupid and self-defeating. It exalts brawn over brain. And the most enduring contributions made to civilization have not been made by brawn, they have been made by brain.