Little Rock

During the 1950s the main tactic of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People was to use the courts to end racial discrimination in the United States. One of its objectives was to end the system of having separate schools for black and white children in the South. For example, the states of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia and Kentucky all prohibited black and white children from going to the same school.

In 1952 the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People appealed to the Supreme Court that school segregation was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court ruled that separate schools were acceptable as long as they were "separate and equal". It was not too difficult for the NAACP to provide information to show that black and white schools in the South were not equal.

After looking at information provided by the NAACP, the Supreme Court announced in 1954 that separate schools were not equal and ruled that they were therefore unconstitutional. Some states accepted the ruling and began to desegregate. This was especially true of states that had small black populations and had found the provision of separate schools extremely expensive.

However, several states in the Deep South, including Arkansas, refused to accept the judgment of the Supreme Court. Daisy Bates, the publisher of Arkansas State Press, started a campaign for desegregate schools in the state.

On 3rd September 1957, the governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, used the National Guard to stop black children from attending the local high school in Little Rock. Woodrow Mann, the reforming mayor of the city, disagreed with this decision and on 4th September telegraphed President Dwight Eisenhower and asked him to send federal troops to Little Rock.

On 24th September, 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower, went on television and told the American people: "At a time when we face grave situations abroad because of the hatred that communism bears towards a system of government based on human rights, it would be difficult to exaggerate the harm that is being done to the prestige and influence and indeed to the safety of our nation and the world. Our enemies are gloating over this incident and using it everywhere to misrepresent our whole nation. We are portrayed as a violator of those standards which the peoples of the world united to proclaim in the Charter of the United Nations."

After trying for eighteen days to persuade Orval Faubus to obey the ruling of the Supreme Court, Eisenhower decided to order paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division, to protect black children going to Little Rock Central High School. The white population of Little Rock were furious that they were being forced to integrate their school and Faubus described the federal troops as an army of occupation.

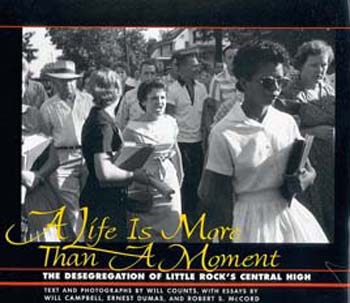

Elizabeth Eckford and the other eight African American students that entered the school (Carlotta Walls, Jefferson Thomas, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Pattillo, Ernest Green, Terrance Roberts, Gloria Ray and Minnijean Brown) suffered physical violence and constant racial abuse. Parents of four of the children lost their jobs because they had insisted in sending them to a white school. Woodrow Mann and his family received death threats and Klu Klux Klan crosses were burnt on his front lawn.

The federal troops left at the end of November and the first black student graduated from Central High School in May 1958.

on 4th September, 1957. The girl shouting is Hazel Massery.

Primary Sources

(1) Alistair Cooke, The Civil Liberties Struggle, Manchester Guardian (7th June, 1950)

The supreme court of the United States handed down yesterday a decision on race relations as historic as anything since the famous case of Dred Scott versus Sanford, which was - among other things - one of the causes of the civil war. In its last decision of the spring term, the supreme court held that the segregation of Negro students in white universities, and of Negroes in railway dining-cars, is unconstitutional in that it denies Negroes the "equal protection of the law" due to all citizens of the United States and guaranteed to them in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which in 1868 proclaimed the citizenship of Negroes, by defining citizens as "all persons born or naturalised in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof ..."

Some states have already given notice that they will defy the court's ruling and seek a rhetorical and more acceptable interpretation of the 'separate but equal' doctrine. Governor Herman Talmadge of Georgia announced in Atlanta yesterday: "As long as I am your governor, Negroes will not be admitted to white schools." In the end, Talmadge and his like will lose. But between the opening of the floodgates of new test cases and the peaceable end of segregation, the old South might well make a final and bloody stand.

(2) Supreme Court ruling on segregation in schools (17th May, 1954)

Segregation of white and coloured children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the coloured children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to retard the educational and mental development of Negro children.

(3) James Eastland, representative from Mississippi, speech in the United States Senate (27th May, 1954)

Separation promotes racial harmony. it permits each race to follow its own pursuits, to develop its own culture, its own institution, and its own civilization. Segregation is not discrimination. Segregation is not a badge of racial inferiority. Segregation is desired and supported by the vast majority of the members of both of the races in the South, who dwell side by side under harmonious conditions. It is the law of nature, it is the law of God, that every race has both the right and the duty to perpetuate itself. Free men have the right to send their children to schools of their own choosing, free from government interference.

(4) Daisy Bates was president of the Arkansas NAACP. She wrote about the struggle to bring an end to school segregation in her book, The Long Shadow of Little Rock (1962).

Faubus' alleged reason for calling out the troops was that he had received information that caravans of automobiles filled with white supremacists were heading toward Little Rock from all over the state. He therefore declared Central High School off limits to Negroes. For some inexplicable reason he added that Horace Mann, a Negro high school, would be off limits to whites.

Then, from the chair of the highest office of the State of Arkansas, Governor Orval Eugene Faubus delivered the infamous words, "blood will run in the streets" if Negro pupils should attempt to enter Central High School.

In a half dozen ill-chosen words, Faubus made his contribution to the mass hysteria that was to grip the city of Little Rock for several months.

The citizens of Little Rock gathered on September 3 to gaze upon the incredible spectacle of an empty school building surrounded by 250 National Guard troops. At about eight fifteen in the morning, Central students started passing through the line of national guardsmen - all but the nine Negro students.

I had been in touch with their parents throughout the day. They were confused, and they were frightened. As the parents voiced their fears, they kept repeating Governor Faubus' words that "blood would run in the streets of Little Rock" should their teenage children try to attend Central - the school to which they had been assigned by the school board.

(5) Elizabeth Eckford was one of the nine African American students who tried to enroll at Little Rock Central High School during September, 1957. She was later interviewed about her attempts to gain entry to the school on the first day of term.

At the corner I tried to pass through the long line of guards around the school so as to enter the grounds behind them. One of the guards pointed across the street. So I pointed in the same direction and asked whether he meant for me to cross the street and walk down. He nodded 'yes.' So, I walked across the street conscious of the crowd that stood there, but they moved away from me.

For a moment all I could hear was the shuffling of their feet. Then someone shouted, 'Here she comes, get ready!' I moved away from the crowd on the sidewalk and into the street. If the mob came at me I could then cross back over so the guards could protect me.

The crowd moved in closer and then began to follow me, calling me names. I still wasn't afraid. Just a little bit nervous.

Then my knees started to shake all of a sudden and I wondered whether I could make it to the center entrance a block away. It was the longest block I ever walked in my whole life.

Even so, I still wasn't too scared because all the time I kept thinking that the guards would protect me.

When I got in front of the school, I went up to a guard again. But this time he just looked straight ahead and didn't move to let me pass him. I didn't know what to do. Then I looked and saw the path leading to the front entrance was a little further ahead. So I walked until I was right in front of the path to the front door.

I stood looking at the school - it looked so big! Just then the guards let some white students through.

The crowd was quiet. I guess they were waiting to see what was going to happen. When I was able to steady my knees, I walked up to the guard who had let the white students in. He too didn't move. When I tried to squeeze past him, he raised his bayonet and then the other guards moved in and they raised their bayonets.

They glared at me with a mean look and I was very frightened and didn't know what to do. I turned around and the crowd came toward me.

They moved closer and closer. Somebody started yelling, 'Lynch her! Lynch her!'

I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the mob - someone who maybe would help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me.

They came closer, shouting, 'No ****** bitch is going to get in our school. Get out of here!'

I turned back to the guards but their faces told me I wouldn't get any help from them. Then I looked down the block and saw a bench at the bus stop. I thought, If I can only get there I will be safe.' I don't know why the bench seemed a safe place to me, but I started walking toward it. I tried to close my mind to what they were shouting, and kept saying to myself, If I can only make it to the bench I will be safe.

When I finally got there, I don't think I could have gone another step. I sat down and the mob crowded up and began shouting all over again. Someone hollered, 'Drag her over to this tree! Let's take care of that ******.' Just then a white man sat down beside me, put his arm around me and patted my shoulder. He raised my chin and said, 'Don't let them see you cry.'

(6) President Dwight Eisenhower, television broadcast on Little Rock (24th September, 1957)

At a time when we face grave situations abroad because of the hatred that communism bears towards a system of government based on human rights, it would be difficult to exaggerate the harm that is being done to the prestige and influence and indeed to the safety of our nation and the world. Our enemies are gloating over this incident and using it everywhere to misrepresent our whole nation. We are portrayed as a violator of those standards which the peoples of the world united to proclaim in the Charter of the United Nations.

(7) Ronald Segal, The Race War (1966)

In 1957 Negroes at Little Rock, the capital of Arkansas, won a court order for the admission of Negro children to the city's all-white Central High School; but Orval Faubus, governor of the state, commanded National Guardsmen to surround the school and prevent the entry of any Negro applicants.

(8) I. F. Stone, I. F. Stone's Weekly (7th October, 1957)

Amid the hand-wringing over Little Rock by the so-called Southern moderates, and the conferences in the White House to negotiate withdrawal of troops, and to let Faubus save face, it is forgotten that for the Negro the law never looked more truly majestic than it does today in Little Rock where for once the bullies of the South have been put on notice that they cannot take out their venom on the Negro and his children.

Quite different is the scene through white Southern eyes. The white South feels like an oppressed minority because the white North has interfered to prevent it from oppressing its Negro minority. The white South feels a victim of injustice, misunderstanding and brute force. That these are exactly what it visits on the helpless Negro who steps out of line merely illustrates the capacity of human beings to go on doing to others what they violently object to when done to themselves.

(9) Orval Faubus was interviewed about the Little Rock crisis after he retired by Jack Bass and Walter DeVries.

Q: How about the decision in 1957 to refuse admittance to black students?

Faubus: It was the only way to keep some black people from being killed. As one black leader said to me in this campaign, he said "Well, Governor Faubus, you probably saved more black lives than you did white lives."

Q: The assertion though is that you based that decision on the evidence from the school principal and him alone.

Faubus: Oh no, I had much evidence. But my first information came from the school principal, or superintendent rather.

Q: You were convinced that that evidence was hard and real?

Faubus: Yes. Wasn't any question about it. I confirmed it from too many sources. And I was trained in intelligence during the war and part of my duties, all during combat, was what you call military intelligence. So you learn something about how to evaluate. You know, how to discount, and how to check something if you're not sure. Sometimes you get a piece of information that sounds fantastic and you think this can't be true and you check it out and find it is. So there's not any question in my mind, none whatsoever.

Q: Wasn't there a court order to admit the students?

Faubus: But I wasn't trying to keep them from integrating. If it had been peaceful they could have gone right on in.

(10) Elizabeth Eckford was interviewed about her experiences at Little Rock High School by Peter Lennon in The Guardian (30th December, 1998)

I was fifteen in September, 1957. At the time I thought the National Guard were there to protect all students. I thought they were there to see that order was maintained. I didn't realise they were there to keep me out of school. My teachers expected there might be name-calling, but I thought that eventually we would be accepted.

I was brought up to believe that students respected adults' orders. That was our expectation, because that was what occurred in the school that we had attended. I had never seen adults appease students who were behaving badly. Many of them did that day, and many of the teachers tried to sit on the fence, tried not to take any side at all. I did not know that Governor Orvel Faubus would side with the segregationists.

Another day, we tried again. The soldiers told us to get into the car, get our heads down and drove us into the basement by the side entrance of the building. So the mob did not realise we were in. When they did they attacked the black news men who were outside. There were FBI men observing all this and they did nothing to stop it. Then Governor Faubus gave the citizens of Little Rock two choices: keep the schools open and de-segregate or close down all the schools. The vote was to close down the schools and for a full year no school, white or black, operated in Little Rock.

Of the thousands of students affected, only a few could afford to send their children to families in other cities or boarding schools out of state. I stayed in town and took a correspondence course. Since my parents were accustomed to paying for my books, this was not so difficult. But four of the nine families had to move out, their parents lost their jobs because of pressure on them not to send their children back to school.

By 1960, the entire state of Arkansas had suffered economically. For years no new industry would come in, and the officials began to change their rhetoric. My definition of a Southern white moderate is someone who reluctantly accepts the law.

(11) Hazel Massery was one of the white students who attempted to stop Elizabeth Eckford and the other eight African Americans from entering Little Rock School (see photograph above). She was interviewed by Peter Lennon in The Guardian (30th December, 1998)

I am not sure at that age what I thought, but probably I overheard that my father was opposed to integration. I vividly remember that the National Guard was going to be there. But I don't think I was old enough to have any convictions of my own yet. I was just mirroring my adult environment. I wasn't following Elizabeth. She happened to come along, the crowd shifted and I was standing in that spot so I just went along with the crowd.

I soon forget about it all. I married as a teenager, right out of school. I was not quite 17. But there was Martin Luther King's Civil Rights activities and gradually you began to think that even though he was a trouble-maker, all the while, deep in your soul, that he was right.

I think motherhood brings out the protection or care in a person. I had a sense of deep remorse that I had wronged another human being because of the colour of her skin. But you are also looking for relief and forgiveness, of course, more for yourself than for the other person.

I called her (Elizabeth Eckford). The first meeting was very awkward. What could I say to her? I thought of something finally and we kind of warmed up. The families are not at ease about this relationship. Housing is still strictly segregated in Little Rock. There is some tension regarding our safety. On one side there are blacks who feel Elizabeth has betrayed them by becoming friends with me, and certain whites feel that I have betrayed them by becoming friends with me, and certain whites feel that I have betrayed our culture. But we have become real friends.