Ida Wells

Ida Wells, the daughter of a carpenter, was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1862. Her parents were slaves but they family achieved freedom in 1865. When Ida was sixteen both her parents and a younger brother, died of yellow fever. At a meeting following the funeral, friends and relatives decided that the five children should be farmed out to various aunts and uncles. Ida was devastated by the idea and to keep the family together, dropped out of High School, and found employment as a teacher in a local Black school.

In 1880 Ida moved to Memphis where she attended Fisk University. Ida held strong political opinions and she upset many people with her views on women's rights. When she was 24 she wrote, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge."

Ida became a public figure in the city when in 1884 she led a campaign against segregation on the local railway. After being forcibly removed from a whites only carriage she successfully sued the Chesapeake, Ohio & South Western Railroad Company. However, this was overturned three years later by a ruling from the Tennessee Supreme Court.

In 1884 Ida began teaching in Memphis. She also wrote articles on civil rights for local newspapers and when she criticised the Memphis Board of Education for under-funding African American schools, she lost her job as a teacher.

Ida used her savings to become part owner of Free Speech, a small newspaper in Memphis. Over the next few years she concentrated on writing about individual cases where black people had suffered at the hands of white racists. This included an investigation into lynching and discovered during a short period 728 black men and women had been lynched by white mobs. Of these deaths, two-thirds were for small offences such as public drunkenness and shoplifting. the first conference of the NAACP she successfully persuaded the organisation to resolve to make lynching a federal crime.

On 9th March, 1892, three African American businessmen were lynched in Memphis. When Ida wrote an article condemning the lynchers, a white mob destroyed her printing press. They declared that they intended to lynch Ida but fortunately she was visiting Philadelphia at the time. Unable to return to Memphis, Ida was recruited by the progressive newspaper, New York Age . She continued her campaign against lynching and Jim Crow laws and in 1893 and 1894 made lecture tours of Britain. While there in 1894 she helped to establish the British Anti-Lynching Committee. Members included James Keir Hardie, Thomas Burt, John Clifford, Isabella Ford, Tom Mann, Joseph Pease, C. P. Scott, Ben Tillett and Mary Humphrey Ward.

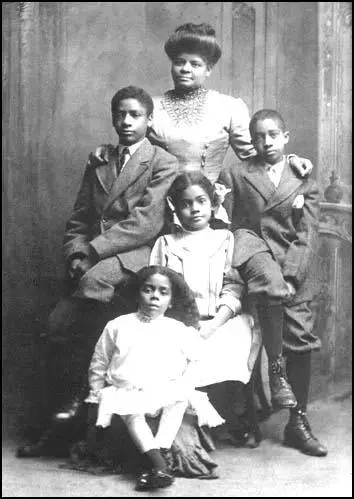

In 1894 Ida married Ferdinand Barnett, the founder of the Conservator , the first African American newspaper in Chicago. Ida gave birth to four children: Charles (1896), Herman (1897), Ida (1901) and Alfreda (1904). She continued her involvement in politics and wrote pamphlets such as Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.

In 1901 Ida published her book, Lynching and the Excuse for It. In the book she argued that the main aim of lynching was to intimidate blacks from becoming involved in politics and therefore maintaining white power in the South.

Ida was also one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909. At the first conference of the NAACP she successfully persuaded the organisation to resolve to make lynching a federal crime.

An early supporter of women's suffrage, Ida created a stir in 1913 when she refused to march at the back with other black delegates during a demonstration organised by the National American Women Suffrage.

Ida, who wrote for the Chicago Tribune, campaigned for racial equality in the United States Army during the First World War. This included publicizing the execution of black soldiers for minor offences while fighting for their country. After her retirement, Ida wrote her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928).

Ida Wells-Barnett died of uremia on 25th March, 1931.

Primary Sources

(1) Ida Wells was one of the leaders of the fight against Jim Crow laws and wrote about this in her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928)

In the ten years succeeded the Civil War thousands of Negroes were murdered for the crime of casting a ballot. As a consequence their vote is entirely nullified throughout the entire South. The laws of the Southern states make it a crime for whites and Negroes to inter-marry or even ride in the same railway carriage. Both crimes are punishable by fine and imprisonment. The doors of churches, hotels, concert halls and reading rooms are alike closed against the Negro as a man, but every place is open to him as a servant.

(2) Ida Wells, New York Age (May, 1892)

Eight Negroes lynched since last issue of the Free Speech. three were charged with killing white men and five with raping white women. Nobody in this section believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men assault white women. If Southern white men are not careful they will over-reach themselves and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

(3) Ida Wells, Crusade for Justice (1928)

All my life I had known that such conditions were accepted as a matter of course. I found that this rape of helpless Negro girls and women, which began in slavery days, still continued without let or hindrance, check or reproof from the church, state, or press until there had been created this race within a race - and all designated by the inclusive term of "colored".

I also found that what the white man of the South practiced as all right for himself, he assumed to be unthinkable in white women. They could and did fall in love with the pretty mulatto and quadroon girls as well as black ones, but they professed an inability to imagine white women doing the same thing with Negro and mulatto men. Whenever they did so and were found out, the cry of rape was raised, and the lowest element of the white South was turned loose to wreak its fiendish cruelty on those too weak to help themselves.

No torture of helpless victims by heathen savages or cruel red Indians ever exceeded the cold-blooded savagery of white devils under lynch law. This was done by white men who controlled all the forces of law and order in their communities and who could have legally punished rapists and murderers, especially black men who had neither political power nor financial strength with which to evade any justly deserved fate. The more I studied the situation, the more I was convinced that the Southerner had never gotten over his resentment that the Negro was no longer his plaything, his servant, and his source of income.

(4) The Newcastle Leader (19th May, 1893)

Yesterday Miss Wells addressed public meetings held afternoon and evening in the Society of Friends Meeting House, Pilgrim Street, Newcastle. Miss Wells is a young lady with a strong American accent, and who speaks with an educated and forceful style, gave some harrowing instances of the injustice to the members of her race, of their being socially ostracized and frequently lynched in the most barbarous fashion by mobs on mere suspicion, and without any trial whatever. These lynchings are on the increase, and have risen from 52 in 1882 to 169 in 1891, and 159 in 1892. Her object in coming to England, she said, was to arouse public sentiment on this subject. England has often shown America her duty in the past, and she has no doubt that England will do so again.

(5) Birmingham Daily Post (18th May, 1893)

A meeting was held yesterday at the Young Men's Christian Association assembly room to hear addresses upon the treatment of Negroes in the southern states of the American Union. Miss Wells in a quiet but effective address said it had been asked why she should have come four thousand miles to tell the people of Birmingham about something that could be dealt with very properly by the local authorities in America. She thought her story would answer that question.

Since 1875 the southern states had been in possession each of its own state government, and the privilege had been used to make laws in every way restrictive and proscriptive of the Negro race. One of the first of these laws was that which made it a state prison offense for black and white to inter-marry. That law was on the statute book of every southern state. Another of these restrictive laws had only been adopted within the last half dozen years. It was one that made it a crime by fine and imprisonment for black and white people to ride in the same carriage.

(6) Ida Wells spoke at several meetings organised by the Society of Friends while in England in 1893. In her autobiography she described travelling back to the United States with members of this organization.

My return voyage was most delightful. First, there were few if any white Americans on board. Second, there were fifteen young Englishmen in one party on their way to visit the World's Fair. I had not met any of them previously, but one or two of them were members of the Society of Friends and they had read about my trip. They were as courteous and attentive to me as if my skin had been of the fairest. It was indeed a delightful experience. All this I enjoyed hugely, because it was the first time I had met any of the members of the white race who saw no reason why they should not extend to me the courtesy they would have offered to any lady of their own race.

(7) Ida Wells was one of the first members of the NAACP. In her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928), Wells points out that the NAACP was concerned about the activities of Booker T. Washington in the struggle for racial equality.

There was an uneasy feeling that Mr. Booker T. Washington and his theories, which seemed for the moment to dominate the country, would prevail in the discussion as to what ought to be done. Although the country at large seemed to be accepting and adopting Mr. Washington's theories of industrial education, a large number agreed with Dr. Du Bois that it was impossible to limit the aspirations and endeavors of an entire race within the confines of the industrial education program.

(8) Ida Wells played an active role in the women suffrage movement. In her autobiography she described a conversation she had with Susan Anthony about Frederick Douglass.

Miss Anthony said when women called their first convention back in 1848 inviting all those who thought that women ought to have an equal share with men in the government, Frederick Douglass, the ex-slave, was the only man who came to their convention and stood up with them. "He said he could not do otherwise; that we were among the friends who fought his battles when he first came among us appealing for our interest in the antislavery cause. From that day until the day of his death Frederick Douglass was an honorary member of the National Women's Suffrage Association. In all our conventions, most of which had been held in Washington, he was the honored guest who sat on our platform and spoke in our gatherings

(9) In 1898 Ida Wells wrote to President McKinley asking him to take action against the lynching of blacks that was taking place in the southern states.

For nearly twenty years lynching crimes have been committed and permitted by this Christian nation. Nowhere in the civilized world save the United States of America do men, possessing all civil and political power, go out in bands of 50 to 5,000 to hunt down, shoot, hang or burn to death a single individual, unarmed and absolutely powerless. Statistics show that nearly 10,000 American citizens have been lynched in the past 20 years. To our appeals for justice the stereotyped reply has been the government could not interfere in a state matter.

(10) Ida Wells, a members of the NAACP, was involved in the protests about Birth of a Nation. In her In her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928), she described how D. W. Griffith defended his film in court.

Mr. D. W. Griffith, the creator of the film, took the stand and denied that there was anything in The Birth of a Nation which could be objected to. D. W. Griffith was a great artist and one of the leading geniuses in presenting photo plays. That he should prostitute his talents in what would otherwise have had the finest picture presented, in an effort to misrepresent a helpless race, has always been a wonder to me. I have often wondered if his failure to establish himself as a moving picture magnate is not because he chose to prostitute his magnificent talents by an unjust and unworthy portrayal of the Negro race.

(11) In 1917 Ida Wells investigated an incident where twelve black soldiers were executed at Houston.

The result of the court-martial of those who had fired on the police and the citizens of Houston was that twelve of them were condemned to be hanged and the remaining members of that immediate regiment were sentenced to Leavenworth for different terms of imprisonment. The twelve were afterward hanged by the neck until they were dead, and, according to the newspapers, their bodies were thrown into nameless graves. This was done to placate southern hatred. It seemed to me a terrible thing that our government would take the lives of men who had bared their breasts fighting for the defence of our country.

(12) In her autobiography, Crusade for Justice, Ida Wells described being threatened with arrest for treason after distributing anti-lynching buttons during the First World War.

One morning very soon after we began distributing these buttons, a reporter from the Herald Examiner came into the office and asked to see one. I gave it to him and told him that the purpose was to give one to every member of our race who wanted to wear one.

The reporter went away with a button, and in less than two hours men from the secret service bureau came into the office with a picture of the button which I had given to the reporter. They inquired for me, showed me the button, and told me that they had been sent out to warn me that if I distributed those buttons I was liable to be arrested.

"On what charge?" I asked. One of the men, the smaller of the two, said, "Why, for treason."

"Will you give us the buttons?" I said no. "Why," he said, "you have criticized the government." "Yes," I said, "and the government deserves to be criticised."

"Well," said the shorter of the two men, "the rest of your people do not agree with you." I said, "Maybe not. They don't know any better or they are afraid of losing their whole skins. As for myself I don't care. I'd rather go down in history as one lone Negro who dared to tell the government that it had done a dastardly thing than to save my skin by taking back what I have said. I would consider it an honour to spend whatever years are necessary in prison as the one member of the race who protested, rather than to be with all the 11,999,999 Negroes who didn't have to go to prison because they kept their mouths shut."