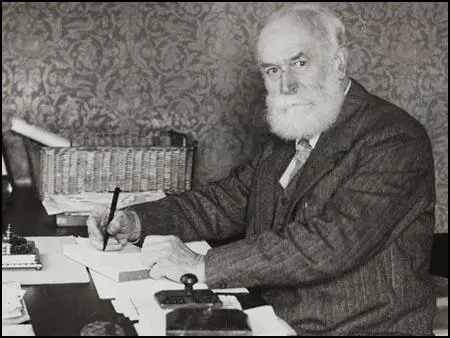

C. P. Scott

Charles Prestwich Scott, the son of Russell Scott, a successful businessman, was born in Bath in 1846. His grandfather, also called Russell Scott, had worked closely with Joseph Priestley to establish the Unitarian movement in Britain.

Charles was educated at Hove House, a Unitarian school in Brighton and Clapham Grammar School. After the passing of the 1854 University Act, Nonconformists were allowed to study at Oxford and Cambridge. Individual colleges could now devise their own entry rules. Scott was rejected by two colleges, Queen's and Christ Church, because he did not have a Church of England baptist certificate. However, he was accepted by Corpus Christi College and he started his studies in October 1865.

While at Oxford, Scott was approached by his cousin, John Taylor, to write for the Manchester Guardian. Taylor, the son of John Edward Taylor, the founder of the newspaper, ran the London office. In 1871 he decided that he needed an editor based in Manchester, and appointed the 25 year old C. P. Scott to the post. It was agreed that Scott should receive a salary of £400 a year and one-tenth of the profits.

In 1874 Scott married Rachel Cook, the daughter of the Professor of History at St Andrews University. Rachel was one of the first students to study at Girton College and was introduced to the Scott family by Barbara Bodichon. Over the next few years Rachel had four children: Madeline (1876), Laurence (1877), John Russell (1879) and Edward Taylor (1883).

Scott took a keen interest in further education and was a trustee of Owens College and a member of its council between 1890 and 1898. C. P. Scott was also an advocate of universal suffrage. His newspaper gave strong support to Jacob Bright's Bill for Women's Suffrage. Scott also joined Elizabeth Butler in her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Act.

John Taylor did not share C. P. Scott's views on parliamentary reform and ordered him not to use the Manchester Guardian to support the campaign. On 29th April, 1892, Taylor wrote to Scott again on this issue: "Your article yesterday for the Female Suffrage Bill was adroitly done, and your display of the cloven foot most discreetly managed; still it was quite visible. I must ask you not to advocate this measure whilst I live."

Although Scott was now receiving 25% of the profits of the Manchester Guardian, Taylor still controlled 75% of the company and had the power to over-rule his editor. Scott no longer received a salary but he did well from this agreement as the profits during this period ranged from £12,000 to £24,000 a year.

In the 1895 General Election, Scott stood as the Liberal Party candidate for North-East Manchester. He won with a majority of 667 and once in the House of Commons identified himself with the left-wing of the party. In Parliament C. P. Scott advocated women's suffrage and reform of the House of Lords.

In 1899 Scott strongly opposed the Boer War. This created a great deal of public hostility and both Scott's house and the Manchester Guardian building had to be given police protection. Sales of the newspaper also dropped during this period. However, despite holding unpopular views on the war, Scott managed to regain his seat in the 1900 General Election. With the help of his able lieutenants, C. E. Montague and L. T. Hobhouse, Scott continued to edit the newspaper during the period he sat in the House of Commons.

When John Taylor died in October 1905, he left instructions in his will that C. P. Scott could buy the Manchester Guardian for £10,000. The trustees were unwilling to obey these demands and eventually Scott had to raise £242,000 to buy the newspaper. This was a high price considering the newspaper only made a profit of £1,200 in 1905.

Scott was now in a position to use the newspaper to advocate women's suffrage. However, he was opposed to the tactics of the Women's Social & Political Union. In 1911 Scott held a meeting with David Lloyd George. He recorded in his diary: "We talked almost entirely of the Women's Suffrage movement and the damage done to it by the militant outrages. I urged that the militants should be ignored and the Suffrage campaign pressed on as though they didn't exist."

Scott initially opposed Britain's involvement in the First World War. Scott supported his friends, John Burns, John Morley and Charles Trevelyan, when they resigned from the government over this issue. However, he refused to join anti-war organizations such as the Union of Democratic Control (UDC). As he wrote at the time: "I am strongly of the opinion that the war ought not to have taken place and that we ought not to have become parties to it, but once in it the whole future of our nation is at stake and we have no choice but do the utmost we can to secure success."

Scott did oppose conscription introduced in 1916 and favoured the attempts made by Arthur Henderson to secure a negotiated peace in 1917. He recorded what David Lloyd George said about a meeting he had with the journalist, Philip Gibbs on the return from the Western Front: "I listened last night, at a dinner given to Philip Gibbs on his return from the front, to the most impressive and moving description from him of what the war (on the Western Front) really means, that I have heard. Even an audience of hardened politicians and journalists were strongly affected. If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they don't know, and can't know. The correspondents don't write and the censorship wouldn't pass the truth. What they do send is not the war, but just a pretty picture of the war with everybody doing gallant deeds. The thing is horrible and beyond human nature to bear and I feel I can't go on with this bloody business."

Scott thought it unwise to impose harsh conditions on Germany after the war had come to an end in 1918. Although Scott was critical of the way David Lloyd George handled the peace negotiations at Versailles he supported him in his struggle with Herbert Asquith. After the Conservative victory in the 1922 General Election, Scott worked hard to unite the Liberal Party. However, his loyal support of Lloyd George made this an impossible task.

Kingsley Martin went to work for the Manchester Guardian in 1927: "C. P. Scott was a remarkable figure. At the age of eighty he was bent nearly double, blind in one eye, but more fierce in expression than any other man I have known. He still rode his bicycle through the muddy and dangerous streets of Manchester, swaying between the tramlines, with white hair and whiskers floating in the breeze, equally oblivious of rain and traffic. Unconsciously, I am sure, he thought that no one in Manchester would hurt him."

C. E. Montague, who was married to C. P. Scott's only daughter, Madeline, died in June, 1929, after working for the Manchester Guardian for thirty-five years. The following month, Scott, after fifty-seven years as editor, decided to retire. Scott had initially expected his eldest son, Laurence Scott, to succeed him as editor. However, while involved in charity work in the Ancoats slums, he caught tuberculosis and died. It was therefore, Edward Scott, the youngest son, who took over from his father. Although officially retired, Charles Prestwich Scott kept a close watch over the newspaper until his death on 1st January, 1932.

It its editorial that week, The New Statesman compared Scott to Lord Northcliffe: "Every newspaper lives by appealing to a particular public. It can only go ahead of its times if it carries its public with it. Success in journalism depends on understanding the public. But success is of two kinds. Northcliffe had a genius for understanding his public and he used it for making money, not for winning permanent influence.... C. P. Scott succeeded in a different way. He had just as much flair, just as acute an understanding of his public as Northcliffe. But his relationship to it was a professional, not a commercial relation. He taught his public to trust his integrity, to rely on the facts he told them, to respect his judgment, and to listen to his criticism. He offered his undivided services. I remember his saying that there was a definite moment in his life, the equivalent of a religious conversion, when he dedicated his life wholly to his paper and the causes it served."

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Prestwich Scott, letter to his father while at Oxford University (1st May, 1866)

On Sunday morning immediately after breakfast, I was summoned for the first time into the awful presence of the dean in his official capacity. He asked my name (being a great philosopher, whose lofty gaze does not usually descend as low as first year men) and desired to know why I had not been in Chapel. I pleaded temporary indisposition, and was dismissed with an injunction not to repeat my offence.

(2) C. P. Scott, wrote to his brother about working on the Manchester Guardian (April, 1871)

With the other people in the office I am on a very pleasant and friendly footing. Acton takes three leaders a week, Couper one, and there is an odd leader (we have two long ones on Wednesday) which may fall to the lot of any one of us. My hours are pretty much as follows - I get up at 7.30, breakfast, read the Guardian thoroughly and walk into town, arriving soon after ten o'clock. I work on all day and walk back for dinner about six o'clock. Read and write in the evening and go to bed soon after ten.

(3) In his diary, C. P. Scott recorded details of a meeting with David Lloyd George about the decision of the WSPU to disrupt meetings held by leading figures in the government. (2nd December, 1911)

We talked almost entirely of the Women's Suffrage movement and the damage done to it by the militant outrages. I urged that the militants should be ignored and the Suffrage campaign pressed on as though they didn't exist. "That's all very well for us," said Lloyd George, "though it's difficult; I don't mind and it doesn't put me out much at meetings or irritate me. I'm used to the rough and tumble and have had to fight my way; so is Churchill, but it's different with Grey; he isn't accustomed to interruption. But what really matters is the effect on the audiences and the public."

(4) C. P. Scott, Manchester Guardian (9th July, 1912)

We do not know whether the present House of Commons will be prepared to do justice to women. A few months ago there can be little doubt that it would, and nothing that has since happened supplies any adequate reason for a change of purpose. The follies and excesses of a small section of women, deeply resented and regretted by the vast majority of women, ought not to be allowed to weigh in the balance against a claim which has been admitted to be just.

(5) C. P. Scott, letter to Manchester and Salford Trades and Labour Council (7th August, 1914)

I am strongly of the opinion that the war ought not to have taken place and that we ought not to have become parties to it, but once in it the whole future of our nation is at stake and we have no choice but do the utmost we can to secure success.

(6) C. P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, wrote a letter to Charles Trevelyan suggesting that he should not publish a pamphlet he had written that raised doubts about the reported atrocities being committed by the Germans in Belgium (5th September, 1914)

It would be expedient to hold back the pamphlet. The war is at present going badly against us and any day may bring more serious news. I suppose that as soon as the Germans have time to turn their attention to us we may expect to see their big guns mounted on the other side of the Channel and their Zeppelins flying over Dover and perhaps London. People will be wholly impatient of any sort of criticism of policy at such a time and I am afraid that premature action now might destroy any hope of usefulness for your organisation (Union of Democratic Control) later. I saw Angell and Ramsay MacDonald yesterday afternoon and found that they had come to the same conclusion.

(7) On the 4th September, 1914, C. P. Scott, recorded details of a meeting he had with David Lloyd George that day.

He (Lloyd George), Beauchamp, Morley and Burns had all resigned from the Cabinet on the Saturday (1st August) before the declaration of war on the ground that they could not agree to Grey's pledge to Cambon (the French ambassador in London) to protect north coast of France against Germans, regarding this as equivalent to war with Germany. On urgent representations of Asquith he (Lloyd George) and Beauchamp agreed on Monday evening to remain in the Cabinet without in the smallest degree, as far as he was concerned, withdrawing his objection to the policy but solely in order to prevent the appearance of disruption in face of a grave national danger. That remains his position. He is, as it were, an unattached member of the Cabinet.

(8) C. P. Scott, letter to Arthur Balfour about the threaten introduction of military conscription (2nd January, 1916)

You know that I was honestly willing to accept compulsory military service, provided that the voluntary system had first been tried out, and had failed to supply the men needed and who could still be spared from industry, and were numerically worth troubling about. Those, I think, are not unreasonable conditions, and I thought that in the conversation I had with you last September you agreed with them. I cannot feel that they had been fulfilled, and I do feel very strongly that compulsion is now being forced upon us without proof shown of its necessity, and I resent this the more deeply because it seems to me in the nature of a breach of faith with those who, like myself - there are plenty of them - were prepared to make great sacrifices of feeling and conviction in order to maintain the national unity and secure every condition needed for winning the war.

(9) C. P. Scott, recorded in his diary comments made by David Lloyd George after he had heard Philip Gibbs speak at a private meeting on 27th December, 1917.

I listened last night, at a dinner given to Philip Gibbs on his return from the front, to the most impressive and moving description from him of what the war (on the Western Front) really means, that I have heard. Even an audience of hardened politicians and journalists were strongly affected. If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they don't know, and can't know. The correspondents don't write and the censorship wouldn't pass the truth. What they do send is not the war, but just a pretty picture of the war with everybody doing gallant deeds. The thing is horrible and beyond human nature to bear and I feel I can't go on with this bloody business.

(10) After the 1922 General Election, the wife of Herbert Asquith, wrote to C. P. Scott criticizing his decision to support David Lloyd George in his campaign to be re-elected (21st November, 1922)

I feel very bitter about Lloyd George; his is the kind of character I mind most, because I feel his charm and recognize his genius; but he is full of emotion without heart, brilliant with intellect, and a gambler without foresight. He has reduced our prestige and stirred up resentment by his folly - in India, Egypt, Ireland, Poland, Russia, America, and France.

(11) C. P. Scott, letter to Henry Nevinson (7th September, 1927)

Will you kindly write us a signed review of this book about Northcliffe. He would be important if only because his rise is the rise of the vast popular press. The tragedy of his life seems to me to lie in the fact that though he knew how to create the instruments not only of profit but of power he had not the least idea what to do with his power when he got it.

(12) Kingsley Martin joined the Manchester Guardian in 1927. Martin later wrote an account of his editor.

C. P. Scott was a remarkable figure. At the age of eighty he was bent nearly double, blind in one eye, but more fierce in expression than any other man I have known. He still rode his bicycle through the muddy and dangerous streets of Manchester, swaying between the tramlines, with white hair and whiskers floating in the breeze, equally oblivious of rain and traffic. Unconsciously, I am sure, he thought that no one in Manchester would hurt him.

(13) King George V, letter to C.P. Scott on his retirement (July, 1929)

For fifty-seven years you have been responsible for the conduct of a great newspaper, and his Majesty, while regretting your resignation, congratulates you on an achievement which must surely be unique in the annals of journalism.

(14) Kingsley Martin, Father Figures (1966)

When C. P. Scott died, the innumerable tributes to him all emphasized his courage and integrity, his humanitarianism and his championship of unpopular causes. They omitted comment on his remarkable astuteness, his diplomatic gift, his caution, his capacity for compromise, his knowledge of when to strike and when to forebear.

He could claim, above all, that he had been right - right about the Boer War, right about Home Rule, right about Women's Suffrage, right about the Versailles Peace Treaty, right about a host of other smaller causes which we have forgotten because they have been won. The influence of the Manchester Guardian was due to the fact that the causes it took up were never run as stunts, taken up in the hot mood and dropped in the cold; they were clearly imagined lines of policy, consistently and moderately pursued year after year, boldly urged in season, persuasively advocated out of season, but never abandoned until victory was achieved.

(15) The New Statesman (January, 1932)

Every newspaper lives by appealing to a particular public. It can only go ahead of its times if it carries its public with it. Success in journalism depends on understanding the public. But success is of two kinds. Northcliffe had a genius for understanding his public and he used it for making money, not for winning permanent influence. He became a millionaire because he was his own most appreciative reader; he instinctively appealed in the most profitable way to the millions of men and women whose tastes and prejudices were the same as his own. He lived by flattering. He did not educate or change his public in any essential; he merely induced it to buy newspapers.

C. P. Scott succeeded in a different way. He had just as much flair, just as acute an understanding of his public as Northcliffe. But his relationship to it was a professional, not a commercial relation. He taught his public to trust his integrity, to rely on the facts he told them, to respect his judgment, and to listen to his criticism. He offered his undivided services. I remember his saying that there was a definite moment in his life, the equivalent of a religious conversion, when he dedicated his life wholly to his paper and the causes it served.