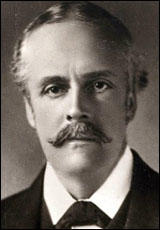

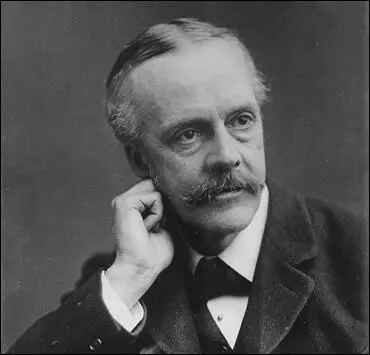

Arthur Balfour

Arthur Balfour was born on the family's Scottish estate in East Lothian on 25th July 1848. Educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, he entered the House of Commons in 1874 as the Conservative MP for Hertford.

In 1878 Balfour became private secretary to his uncle, the Marquess of Salisbury, who was Foreign Secretary in the Conservative government headed by Benjamin Disraeli.

In the 1885 General Election Balfour was elected to represent the East Manchester constituency. The Marquess of Salisbury, who was now Prime Minister, appointed him as his Secretary for Scotland. Other posts during the next few years included Chief Secretary of Ireland (1887), First Lord of the Treasury (1892) and leader of the House of Commons (1892).

Balfour replaced his uncle as Prime Minister in 1902. The most important events during his premiership included the 1902 Education Act and the ending of the Boer War. The topic of Tariff Reform split Balfour's government and when he resigned in 1905, Edward VII invited Henry Campbell-Bannerman to form a government. Campbell-Bannerman accepted and in the 1906 General Election that followed the Liberal Party had a landslide victory.

Balfour remained leader of the Conservative Party until he was replaced by Andrew Bonar Law in 1911. He returned to government when in 1915 Herbert Asquith offered him the post of First Lord of the Admiralty in Britain's First World War coalition government. The following year, David Lloyd George, the new Prime Minister, appointed him as Foreign Secretary, and consequently was responsible for the Balfour Declaration in 1917 which promised Zionists a national home in Palestine.

Henry Hamilton Fyfe, who worked for The Times reported: "I saw that Balfour was not a great man. He had charm and wit; he could be energetic when he chose, but he chose very seldom; he had a marvellously acute mind, but he feared the logic of its conclusions. He was truly bored by almost everything, and he was born lazy. I recall one of his official secretaries telling me furiously how Balfour was primed for a critical debate, given sheaves of notes, told what his line of argument must be. And then, spluttered Robert Morant, he stuffed all the papers in his pocket without looking at them, and made a speech that missed all the essential points. After such episodes he would be more than usually charming, and would ask with a smile and a slight lift of his shoulders, What does it matter?"

Balfour left Lloyd George's government in 1919 but returned to office when he served as Lord President of the Council (1925-29) in the Conservative government headed by Stanley Baldwin.

Arthur Balfour died on 19th March 1930.

Primary Sources

(1) Henry Hamilton Fyfe was a reporter on The Times when he first met Arthur Balfour.

I saw that Balfour was not a great man. He had charm and wit; he could be energetic when he chose, but he chose very seldom; he had a marvellously acute mind, but he feared the logic of its conclusions. He was truly bored by almost everything, and he was born lazy. I recall one of his official secretaries telling me furiously how Balfour was primed for a critical debate, given sheaves of notes, told what his line of argument must be. "And then," spluttered Robert Morant, "he stuffed all the papers in his pocket without looking at them, and made a speech that missed all the essential points." After such episodes he would be more than usually charming, and would ask with a smile and a slight lift of his shoulders, "What does it matter?"