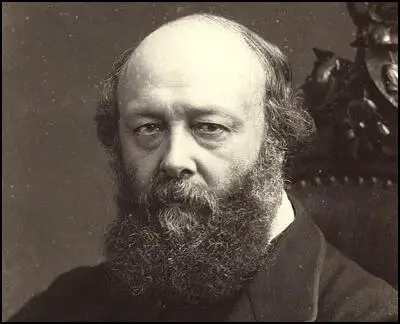

Robert Cecil

Robert Cecil, son of the 2nd Marquis of Salisbury, was born at Hatfield House in 1830. Cecil was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford.

A supporter of the Conservative Party Cecil was elected to represent Stamford in 1853. He was granted the title of Lord Cranborne on the death of his brother in 1865. Cranborne played an important role in the defeat of the Parliamentary Reform Bill proposed by William Gladstone in 1866.

After Gladstone was forced to resign from office, the new prime minister, Lord Derby, appointed Cranborne as his Secretary for India. He strongly opposed the proposal by Benjamin Disraeli to introduce his own parliamentary reform bill. When he realised he was unable to stop Disraeli's 1867 Reform Act he resigned from the cabinet. He later argued: "Unfortunately for Conservatism, its leaders belong solely to one class; they are a clique composed of members of the aristocracy, land-owners, and adherents whose chief merit is subserviency. The party chiefs live in an atmosphere in which a sense of their own importance and of the importance of their class interests and privileges is exaggerated, and to which the opinions of the common people can scarcely penetrate."

In 1868 Robert Cecil succeeded his father as the 3rd Marquis of Salisbury. In 1874 Salisbury returned to government as Benjamin Disraeli's Secretary for India. Four years later he replaced Lord Derby as Foreign Secretary. 1903.

On the death of Benjamin Disraeli in 1878 the Marquis of Salisbury became leader of the Conservative Party. However, he had to wait until the general election of 1885 before he became Prime Minister. He argued in a letter to Randolph Churchill that he found government difficult: "We have to give some satisfaction to both the upper classes and the masses. This is especially difficult with the upper classes - because all legislation is rather unwelcome to them, as tending to disturb a state of things with which they are satisfied. It is evident, therefore, that we must work at less speed and at a lower temperature than our opponents. Our bills must be tentative and cautious, not sweeping and dramatic."

He was replaced by William Gladstone briefly in 1886 but also headed the Conservative governments between 1886-92 and 1895-1902. Salisbury supported the policies that led to the Boer War (1899-1902).

Robert Cecil, the Marquis of Salisbury, retired from public life in July 1902 and died the following year on 22nd August, 1903.

Primary Sources

(1) Marquis of Salisbury, letter to Lord Randolph Churchill (7th November, 1886)

We have to give some satisfaction to both the upper classes and the masses. This is especially difficult with the upper classes - because all legislation is rather unwelcome to them, as tending to disturb a state of things with which they are satisfied. It is evident, therefore, that we must work at less speed and at a lower temperature than our opponents. Our bills must be tentative and cautious, not sweeping and dramatic.

(2) G. C. Bartley, a Conservative Party Agent, was angry when the Marquis of Salisbury's Cabinet included two of his nephews (22nd October, 1898)

It becomes clearer after every appointment that though men may work their hearts out and make every sacrifice financial and otherwise when the Conservative party is in opposition and in difficulties, yet in prosperous times all is forgotten and all honours, emoluments and places are reserved for the friends and relations of the favoured few, many of whom were in the nursery while some of us were fighting uphill battles for the party.

(3) J. A. Gorst, helped to reorganise the Conservative Party in the 1870s. In The Fortnightly Review in 1882 he wrote an article called Tory Democracy.

Unfortunately for Conservatism, its leaders belong solely to one class; they are a clique composed of members of the aristocracy, land-owners, and adherents whose chief merit is subserviency. The party chiefs live in an atmosphere in which a sense of their own importance and of the importance of their class interests and privileges is exaggerated, and to which the opinions of the common people can scarcely penetrate.