1867 Reform Act

In March 1860 Lord John Russell attempted to introduce a new Parliamentary Reform Act that would reduce the qualification for the franchise to £10 in the counties and £6 in towns, and effecting a redistribution of seats. Many people in the Liberal Party were opposed to the measure. One MP warned of the dangers of handling the vote to "great masses of half-educated men". He argued that once trade unionists had the vote they would demand the reduction of the working day to "eight hours".

Benjamin Disraeli, the Conservative Party MP, was strongly against this measure because it enfranchised 203,000 people in the boroughs and these would cast their votes "all of one class, bound together by the same entitlements and habits - we must recollect that half the boroughs are already under the influence of the new class... we are conferring power on a class".

Lord Palmerston, the prime minister, was also opposed to parliamentary reform. He told Lord Russell that his proposal was causing "excitement in the working class" and would give "great power to the agitating but secret leaders' of the unions". He went on to say: "The direct consequence would be an increased and plausible cry for the ballot and the introduction of men into the House of Commons who would be following impulses not congenial to our institutions... Your intended course is openly disapproved of by all the intelligent and respectable classes." Without his support, Lord Russell's proposals did not become law. (1)

Liberal Party and Parliamentary Reform

William Gladstone, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, had been a member of the Conservative Party who had been totally opposed to parliamentary reform in the early part of his career. However, his views changed during a tour of the cotton districts and had been "favourably impressed by working-class qualities". Encouraged by the veteran radical John Bright, he became convinced that large numbers of working-class men could be trusted to exercise the franchise responsibility. (2)

On 11th May 1864, Gladstone argued in the House of Commons that it was a scandal that only one-tenth of those with a vote were "working men" and that "every man who is not presumably incapacitated by some consideration of personal unfitness or of political danger, is morally entitled to come within the pale of the constitution". He went on to say that "I do not recede from the protest I have previously made against sudden, or violent, or excessive or intoxicating change.... Hearts should be bound together by a reasonable extension, at fitting times and among selected portions of the people, of every benefit and every privilege that can be justly conferred upon them." (3)

This speech upset Lord Palmerston and Gladstone was forced to apologize. "I have never exhorted the working men to agitate for the franchise, and I am at a loss to conceive what report of my speech can have been construed by you in such a sense. I argued as strongly as I could against the withdrawal of the Reform Bill in 1860. I think the party which supports your Government has suffered and is suffering and will much more seriously suffer from the part which is a party it has played within these recent years, in regard to the franchise". (4)

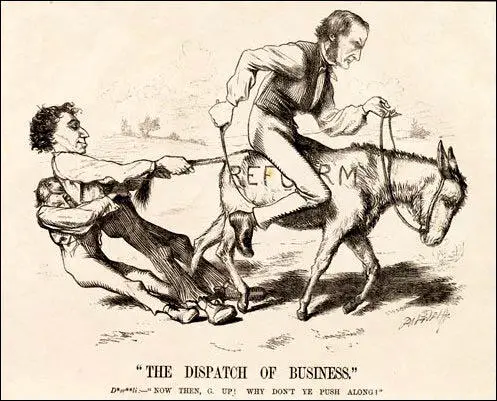

Too soon, Too soon! You mustn't go yet!"

John Tenniel, Punch Magazine (28th May, 1864)

On 23rd February, 1865, George Odger, Benjamin Lucraft, George Howell, William Allan, Johann Eccarius, William Cremer and several other members of the International Workingmen's Association established the Reform League, an organisation to campaign for one man, one vote. Karl Marx told Friedrich Engels "The International Association has managed so to constitute the majority on the committee to set up the new Reform League that the whole leadership is in our hands". (5)

The organization received financial and political support from middle-class radicals such as Peter Alfred Taylor, John Bright, Charles Bradlaugh, John Stuart Mill, Henry Fawcett, Titus Salt, Thomas Perronet Thompson, Samuel Morley and Wilfrid Lawson. Taylor was appointed vice-president and often spoke at public meetings. (6)

On the death of Lord Palmerston in July 1865, Earl Russell became prime minister. On 12th March 1866, William Gladstone introduced the government's new reform bill with the vote going to occupiers of proper in the boroughs worth £7 in rent a year. Gladstone had calculated that while increasing the number of working-class voters, it would still have left them a minority of the total electorate. Probably about one in four men would have been able to vote, instead of the existing one in five. (7)

Gladstone argued: "The £7 franchise will certainly work in a different manner... The wages of a man occupying such a house would be a little under 26s a week. That sum is undoubtedly unattainable by the peasantry, and by mere hand labour, except in very rare circumstances, but it is generally attainable by artisans and skilled labourers... To give the vote to £6 householders... would be to transfer the balance of political power in the boroughs to the working classes... We cannot consent to look upon this addition - considerable though it may be - of the working classes, as if it were

an addition fraught with nothing but danger; we cannot look upon it as a Trojan Horse... filled with armed men bent on ruin, plunder and conflagration." (8)

Several Liberal MPs objected to this measure. Robert Lowe complained: "Is it not certain that in a few years from this the working men will be in a majority? Is it not certain that causes are at work which will have a tendency to multiply the franchise - that the £6 houses will become £7 ones, and that £9 houses will expand to £10? There is no doubt an immense power of expansion; and therefore... it is certain that sooner or later we shall see the working classes in majority in the constituencies. Look at what that implies... If you want venality, if you want ignorance, if you want drunkenness, and facility for being intimidated; or if, on the other hand, you want impulsive, unreflecting, and violent people, where do you look for them in the constituencies? We know what those people are who live in small houses... The first stage, I have no doubt will be an increase of corruption, intimidation, and disorder... The second will be that the working men of England, finding themselves in a full majority of the whole constituency, will awake to a full sense of their power." (9)

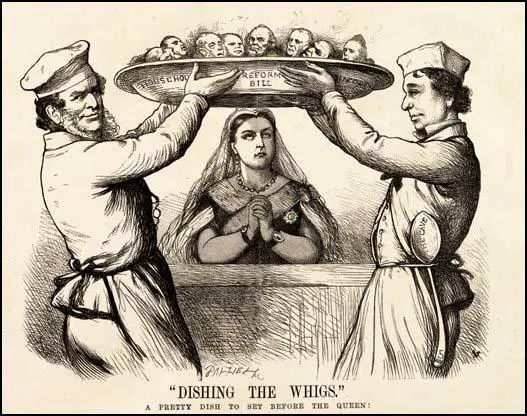

With Conservative opposition to the measure, Russell's government found it impossible to get the bill passed by the House of Commons. On 19th June 1866, Russell's administration resigned. Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, became the new Prime Minister. The Conservative Party were once again in power.

The Reform League responded by organising "a great street procession and meeting, 30,000 strong, in support of the popular demand for household suffrage... the London press for days after the procession had marched through the principal streets of the fashionable West End, teemed with half-frightened references to its military aspects, good marching, admirable order, well closed column and complete discipline." (10)

Lord Russell retired in 1867 and Gladstone became leader of the Liberal Party. Gladstone made it clear that he was in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, the new government, led by Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, was now sympathetic to the idea. The Conservatives knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Benjamin Disraeli "feared that merely negative and confrontational responses to the new forces in the political nation would drive them into the arms of the Liberals and promote further radicalism" and decided that the Conservative Party had to change its policy on parliamentary reform. (11)

Benjamin Disraeli

Disraeli, the new leader of the House of Commons, argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. He reasoned that if the Conservatives could pilot a reform bill through Parliament, they might gain politically as the newly enfranchised in the boroughs might well vote Conservative out of gratitude. At the same time they could make sure the bill had the necessary precautions to preserve aristocratic power in the counties.

In March 1867 Disraeli proposed his new Reform Act. It was a more moderate set of proposals than had been suggested by Gladstone. Fewer working-class males would get the vote and in addition, university graduates, members of the learned professions and those with £50 savings were to have extra votes. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, resigned in protest against this proposed extension of democracy. However, as Disraeli explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy." (12)

On 21st March, 1867, Gladstone made a two hour speech in the House of Commons, exposing in detail the inconsistencies of the bill. On 11th April Gladstone proposed an amendment which would allow a tenant to vote whether or not he paid his own rates. Forty-three members of his own party voted with the Conservatives and the amendment was defeated. Gladstone was so angry that apparently he contemplated retirement to the backbenches. (13)

Members of the Reform League still advocated the need for universal suffrage. At a large rally in Birmingham, George Nuttall attacked both the Conservatives and Liberals for preventing the introduction of democracy: "The House of Commons hated reform and would never grant it until they could not withhold it. The landlords, army lords, navy lords and law lords, who looked eagerly for a share of taxes for themselves and their dependants, would never let the people's nose from the grindstone if they could help it. But the people had the power in their hands if only they knew how to use it. Let them set their backs up, and show their bristles, and they would get the Reform Bill they wanted. They must show they are prepared to burst open the doors of the House of Commons should they be kept persistently closed against them. He hoped they were not coming to an end of a peaceful agitation... but when an aristocracy declared that the people should not be heard in the councils of the nation... that was a very dangerous and criminal thing. The people should rise in their might and majesty. If like the raging sea they should sweep on in their righteous indignation, every barrier set up against them - the aristocracy itself - might be swept into oblivion for ever. (14)

On 18th April, 1867, the Reform League's executive council met in London and unanimously condemned Disraeli's Bill as "partial and oppressive" and reaffirmed their commitment to "a vote for a man because he is a man". Charles Bradlaugh called for a national demonstration to take place in Hyde Park. It was pointed out that this would be breaking the law but Bradlaugh's motion was passed by five votes to three. The following day placards started to go up all over the country announcing a mass demonstration for universal manhood suffrage on 6th May. (15)

Spencer Walpole, the Home Secretary, announced that attending such a meeting would be illegal and that "all persons are hereby warned and admonished that they will attend any such meeting at their peril, and all her Majesty's loyal and faithful subjects are required to abstain from attending, aiding or taking part in any such meeting, or from entering the Park with a view to attend, aid or take part in any such meeting." (16)

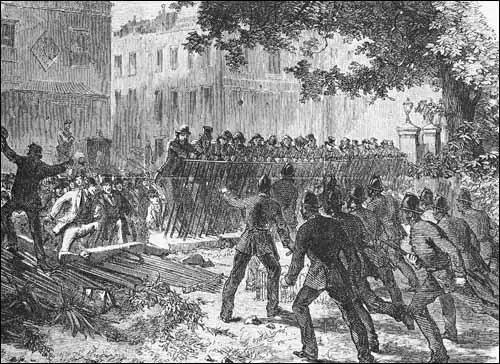

The Government arranged for troops of Hussars to be deployed in the park and thousands of special constables were sworn in. However, so many demonstrators turned up it was decided to back down. "As always with such demonstrations, versions of the numbers varied hugely - from 20,000 in some Tory papers to 500,000 in the League accounts. Some proof that the latter figure was closer to the reality came from the 14 separate platforms from which the most accomplished speakers could not make themselves heard." (17)

It was the first time that any political organization representing the working class had openly and successfully defied the law. Bradlaugh commented that the reformers who had been killed at Peterloo were now at last victorious. The newspapers called for the arrests of the leaders of the Reform League. The government decided that this would be too dangerous and instead, Walpole, the Home Secretary, resigned.

Disraeli realised that he had to make his Reform Bill more popular with the working class. On 20th May he accepted an amendment from Grosvenor Hodgkinson, which added nearly half a million voters to the electoral rolls, therefore doubling the effect of the bill. Gladstone commented: "Never have I undergone a stronger emotion of surprise than when, as I was entering the House, our Whip met me and stated that Disraeli was about to support Hodgkinson's motion." (18)

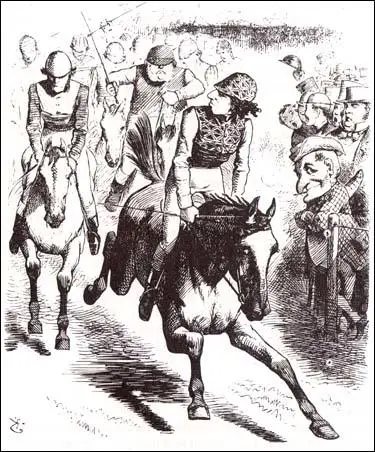

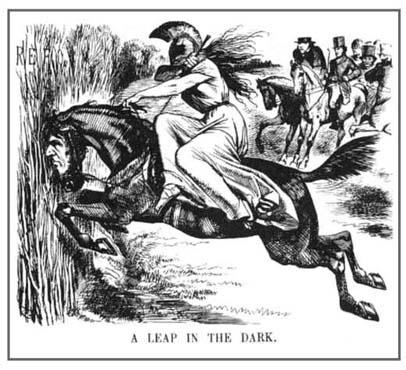

"The Derby, 1867, Dizzy wins with Reform Bill"

John Tenniel, Punch Magazine (25th May, 1867)

Some MPs condemned the move. Robert Lowe, the MP for the ancient pocket borough at Calne complained that this would give the vote to "Wiltshire labourers" earning "eight shillings a week". He feared that these people would not vote for either the Liberal or Conservative candidates: "What will their politics be? With every disposition to speak favourably of them, their politics must take one form or another of socialism" and with this reform "we are going to make a revolution". (19)

John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, was a leading supporter of women's suffrage and wanted to amend the bill by replacing the term "man" by "person". He argued: "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together." (20)

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73. Gladstone voted against the amendment. (21)

1867 Reform Act

Other amendments were accepted: Out went the "dual vote" which allowed people with property to vote in town and country. The clause that would give extra votes for people with savings or education. So did the requirement that ratepayers would need to show two years' residence - the condition was reduced to one year. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, complained that "all the precautions, guarantees, and securities in the Bill" had disappeared. He told Disraeli: "You are afraid of the pot boiling over. At the first threat of battle you throw your standard in the mud". (22)

Benjamin Disraeli dismissed these points by right-wing members of his party, by claiming that this reform will guarantee peace in the years to come: "England is safe in the race of men who inhabit her, safe in something much more precious than her accumulated capital - her accumulated experience. She is safe in her national character, in her fame and in that glorious future which I believe awaits her." (23)

William Gladstone decided not to take part in the debate on the third reading of the bill as he feared it would have a negative reaction: "A remarkable night. Determined at the last moment not to take part in the debate: for fear of doing mischief on our own side." (24) Without provocation from Gladstone the bill was passed in the House of Commons without division. The House of Lords also agreed to pass Disraeli's Reform Act on 15th August, 1867. (25)

The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. (26)

Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, one of the most reactionary figures in England, wrote to a friend welcoming the fact that it was the Conservative Party that had introduced this reform as it damaged William Gladstone and the Liberal Party: "The most wonderful thing is the rise of Disraeli. It is not the mere assertion of talent. He has been able to teach the House of Commons almost to ignore Gladstone, and at present lords it over him, and, I am told, says that he will hold him down for twenty years." (27)

The 1868 General Election proved Wilberforce wrong as the new working class electorate overwhelming supported the Liberal Party. More than a million votes were cast. This was nearly three times the number of people who voted in the previous election. The Liberals won 387 seats against the 271 of the Conservatives. Robert Blake, the author of The Conservative Party from Peel to Churchill (1970) believes the substantial gains in the large cities was an important factor in Gladstone's victory. (28)

Primary Sources

(1) William Gladstone, letter to Lord Palmerston (11th May, 1864)

I am warmly in favour of an extension of the Borough Franchise, I hope I did not commit the Government to anything: nor myself to a particular form of franchise. I stated that I wished to leave the form and figure open; that I was for a sensible and considerable, but not excessive enlargement.

(2) William Gladstone, letter to Lord Palmerston (13th May, 1864)

I have never exhorted the working men to agitate for the franchise, and I am at a loss to conceive what report of my speech can have been construed by you in such a sense. I argued as strongly as I could against the withdrawal of the Reform Bill in 1860. I think the party which supports your Government has suffered and is suffering and will much more seriously suffer from the part which is a party it has played within these recent years, in regard to the franchise.

(3) William Gladstone, letter to Lord Palmerston (23rd May, 1864)

My speech cannot I admit be taken for less than a declaration that, when a favourable state of opinion and circumstances shall arise, the working class ought to be enfranchised to some extent as was contemplated in the Reform Bill of 1860.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)