George Odger

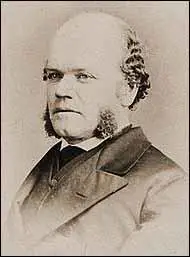

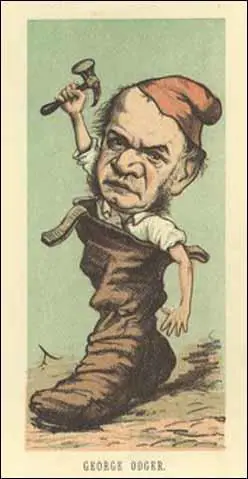

George Odger, the son of John Odger, a Cornish miner, was born in Roborough in 1813. After attending the village school, he became a shoemaker at the age of ten. He became an active trade unionist and "employers marked him as a man not to be hired if it was possible to avoid it." (1)

Odger moved to London, where he became active in the Ladies' West End Shoemakers' Society. Odger, who rose to prominence in delegate meetings of London trades to support building workers in the 1859 strike and lock-out, and helped to initiate the London Trades Council, succeeding George Howell as secretary in 1862. It has been pointed out that he was "a first-class craftsman, he was the only significant labour leader of his generation to practise his trade throughout his life". (2)

The historian Eric Hobsbawm has argued that in the early 1860s there was "a curious amalgam of political and industrial action, of various kinds of radicalism from the democratic to the anarchist, of class struggles, class alliances and government or capitalist concessions... but above all it was international, not merely because, like the revival of liberalism, it occurred simultaneously in various countries, but because it was inseparable from the international solidarity of the working classes." (3)

George Odger and Trade Unionism

Odger promoted the cause of parliamentary suffrage through the Manhood Suffrage and Vote by Ballot Association, of which he became the chairman in 1862. Odger was instrumental in persuading the labour newspaper The Bee-Hive to reverse its pro-Confederate position in the American Civil War and spoke at a meeting held at St James's Hall on 26th March 1863 in support of Abraham Lincoln. He was also involved in welcome to Giuseppe Garibaldi and in meetings to express sympathy with the Polish revolt in 1863. (4)

A group of trade unionists that became known collectively as the "junta" urged the establishment of an international organisation. This included George Odger, Robert Applegarth, Benjamin Lucraft, William Allan and Johann Eccarius. "The aim of the Junta was to satisfy the new demands which were being voiced by the workers as an outcome of the economic crisis and the strike movement. They hoped to broaden the narrow outlook of British trade unionism, and to induce the unions to participate in the political struggle". (5)

George Odger became the secretary of the London Trades Council. Karl Marx, who heard him speak at a public meeting and commented that "the working men themselves spoke very well indeed, without a trace of bourgeois rhetoric". At a meeting with French trade unionists Odger wrote an Address to the Workmen of France from the Working Men of England, "proposing that they should formalise their cross-Channel solidarity". (6)

On September 28, 1864, an international meeting for the reception of French trade unionists took place in St. Martin’s Hall in London. The meeting was organised by George Howell and attended by a wide array of radicals including Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The historian Edward Spencer Beesly was in the chair and he advocated "a union of the workers of the world for the realisation of justice on earth". (7)

In his speech, Beesly "pilloried the violent proceedings of the governments and referred to their flagrant breaches of international law. As an internationalist he showed the same energy in denouncing the crimes of all the governments, Russian, French, and British, alike. He summoned the workers to the struggle against the prejudices of patriotism, and advocated a union of the toilers of all lands for the realisation of justice on earth." (8)

International Workingmen's Association

The new organisation was called the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA). Karl Marx attended the meeting and he was asked to become a member of the General Council that consisted of two Germans, two Italians, three Frenchmen and twenty-seven Englishmen (eleven of them from the building trade). Marx was proposed as President but as he later explained: "I declared that under no circumstances could I accept such a thing, and proposed Odger in my turn, who was then in fact re-elected, although some people voted for me despite my declaration." (9)

The General Council met for the first time on 5th October. George Odger was elected as President and William Cremer as Secretary. After "a very long and animated discussion" the Council could not agree on a programme. Johann Eccarius privately told Marx: "You absolutely must impress the stamp of your terse yet pregnant style upon the first-born child of the European workmen's organisation". (10)

Karl Marx agreed to outline the purpose of the organization. The General Rules of the International Workingmen's Association was published in October 1864. Marx's introduction pointed out what they hoped to achieve: "That the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves, that the struggle for the emancipation of the working classes means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule... That the emancipation of labor is neither a local nor a national, but a social problem, embracing all countries in which modern society exists, and depending for its solution on the concurrence, practical and theoretical, of the most advanced countries." (11)

Friedrich Engels also joined the General Council but refused to to accept the office of treasurer: "Citizen Engels objected that none but working men ought to be appointed to have anything to do with the finances". Marx was asked to draw up the fundamental documents of the new organisation. He admitted that "It was very difficult to manage things in such a way that our views could secure expression in a form acceptable to the Labour movement in its present mood. A few weeks hence these British Labour leaders will he hobnobbing with Bright and Cobden at meetings to demand an extension of the franchise. It will take time before the reawakened movement will allow us to speak with the old boldness." (12)

Over the next few months other European radicals such as Wilhelm Liebknecht, August Bebel, Élisée Reclus, Ferdinand Lassalle, William Greene, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Friedrich Sorge and Louis Auguste Blanqui joined the organisation. Mikhail Bakunin was aware of the growth of the IWMA and after forming the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, he proposed a merger between the two organisations on equal terms, where he would effectively become co-president of the IWMA. This idea was rejected but in 1868 it was agreed to allow the Alliance of Socialist Democracy to become an ordinary affiliate organisation. (13)

1867 Reform Act

George Odger remained active in the struggle for parliamentary reform. On 23rd February, 1865, Odger, Benjamin Lucraft, George Howell, William Allan, Johann Eccarius, William Cremer and several other members of the International Workingmen's Association established the Reform League, an organisation to campaign for one man, one vote. Karl Marx told Friedrich Engels "The International Association has managed so to constitute the majority on the committee to set up the new Reform League that the whole leadership is in our hands". (14)

On 2nd July 1866 the Reform League organised "a great street procession and meeting, 30,000 strong, in support of the popular demand for household suffrage... the London press for days after the procession had marched through the principal streets of the fashionable West End, teemed with half-frightened references to its military aspects, good marching, admirable order, well closed column and complete discipline." (15)

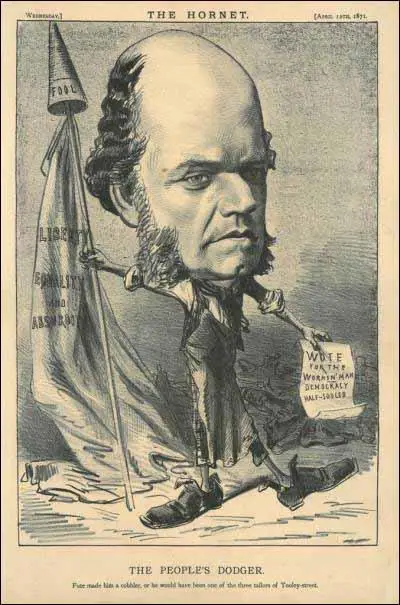

William Gladstone, the new leader of the Liberal Party, made it clear that he was in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, they knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the House of Commons, argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later Lord Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. However, as he explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy." (16)

Odger and other Reform League members had campaigned for adult suffrage but the government's proposals imposed strict restrictions on who could vote. At one meeting Odger declared that "nothing short of manhood suffrage would satisfy the working people". He went onto argue the vote would "prevent the labourer working for eight shillings a week." (17)

In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone and his followers and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. (18)

It has been argued that the passing of the 1867 Reform Act had made the British working class less radical. Odger attempted to stand at Chelsea in 1868 but failed to win the Liberal Party nomination. The same thing happen in Stafford in 1869 and Bristol 1870. He did stand in Southwark in 1870 but lost to the Conservative Party candidate by 304 votes. (19)

The Spectator reported that he was the first working-class candidate to win more than 4,500 votes: "Nevertheless the result is that, for the first time, a member of the artizan class has polled upwards of 4,500 votes, and a considerably greater number of votes than a most wealthy, respectable, and benevolent member of the middle-class, who, in this borough, had every advantage that local connection could give him. That alone should be a pledge to members of the operative class that if they steadily persevere in their attempts to break down the class-feeling which at present excludes them from the House of Commons, they will soon succeed, and have quite sufficient success to secure to the House of Commons a very adequate infusion of the poorest, but by no means the least acute and energetic, class of the English people." (20)

The novelist, Henry James, was dismissive of his attempts to become a member of the House of Commons: "George Odger... was an English radical agitator, of humble origin, who had distinguished himself by a perverse desire to get into Parliament. He exercised, I believe, the useful profession of shoemaker, and he knocked in vain at the door that opens but to golden keys." (21) However, Paul Foot has argued that Odger showed that it would not be long before working-class candidates would soon be elected to the House of Commons. (22)

Land and Labour League

In October 1869 George Odger helped to establish the Land and Labour League. Its formation was precipitated by discussion of the land question at the IWMA Basle Congress earlier that year. The League advocated the full nationalisation of land and was considered to be a republican working-class movement. Other members included Charles Bradlaugh, Johann Eccarius and Benjamin Lucraft. (23) After making one speech he was "set upon by a Conservative mob... and was severely beaten, suffering injuries that confined him for some time". (24)

The IWMA gave its support to strikes taking place in Europe. The financial help given by British trade unions to the striking Paris bronze workers led to their victory. The IWMA was also involved in helping Geneva builders and Basle silk-weavers. Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel were gradually building up support for the organisation in Germany. David McLellan points out that the IWA was "steadily gaining in size, success and prestige". (25)

Karl Marx pointed out that: "The International was founded in order to replace the socialist and semi-socialist sects with a genuine organisation of the working class for its struggle... Socialist sectarianism and a real working-class movement are in inverse ratio to each other. Sects have a right to exist only so long as the working class is not mature enough to have an independent movement of its own: as soon as that moment arrives sectarianism becomes reactionary... The history of the International is a ceaseless battle of the General Council against dilettantist experiments and sects." (26)

Later Years

At first George Odger gave his support to the Paris Commune but was appalled by the scale of the violence. He also disagreed with the views of Karl Marx, that were expressed in The Civil War in France (1871) and along with Benjamin Lucraft decided to resign from the General Council of International Workingmen's Association. (27) According to Boris Nicolaevsky "as cautious and far-sighted individuals and members of royal commissions and friends of some of the very best people, had long since begun to experience a sensation of discomfort". (28)

Although more radical than contemporaries like George Howell and Robert Applegarth, "he was never a socialist or a revolutionary, believing that working-class advance could be achieved only by legitimate political and industrial means... a brilliant orator, effective in parliamentary deputations, he was a popular leader but lacked the capacity for sustained administrative tasks." (29)

George Odger died from congestion of the lungs on 4th March 1877. Odger was buried on the 10th March, and funeral eulogies were delivered by Henry Fawcett and Edward Spencer Beesly. However, not everyone was sympathetic to the politics of Odger. Henry James described the funeral in the Lippincott's Monthly Magazine: "The element of the grotesque was very noticeable to me in the most striking collection of the shabbier English types that I had seen since I came to London. The occasion of my seeing them was the funeral of Mr. George Odger, which befell some four or five weeks before the Easter period.... I emerged accidentally into Piccadilly at the moment they were so engaged, and the spectacle was one I should have been sorry to miss. The crowd was enormous, but I managed to squeeze through it and to get into a hansom cab that was drawn up beside the pavement, and here I looked on as from a box at a play. Though it was a funeral that was going on I will not call it a tragedy; but it was a very serious comedy. The day happened to be magnificent - the finest of the year. The funeral had been taken in hand by the classes who are socially unrepresented in Parliament... The hearse was followed by very few carriages, but the cortege of pedestrians stretched away in the sunshine, up and down the classic gentility of Piccadilly, on a scale that was highly impressive. Here and there the line was broken by a small brass band - apparently one of those bands of itinerant Germans that play for coppers beneath lodginghouse windows; but for the rest it was compactly made up of what the newspapers call the dregs of the population. It was the London rabble, the metropolitan mob, men and women, boys and girls, the decent poor and the indecent, who had scrambled into the ranks as they gathered them up on their passage, and were making a sort of solemn spree of it." (30)

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Wheen, Karl Marx (1999)

It was not until about 1860 that the proletariat began to wake from its long doze. The London Trades Council, founded in 1860, was behind much of this activity. It organised a demonstration to welcome the Italian liberator Giuseppe Garibaldi (who drew a crowd of about 50,000), and in March 1863 it held a public meeting at St James's Hall to pledge support for Abraham Lincoln's fight against slavery in the American Civil War. Marx, who made a rare journey into town for the occasion, was pleased to note that "the working men themselves spoke very well indeed, without a trace of bourgeois rhetoric". But one shouldn't overlook the unwitting contribution of Napoleon III, who paid for a delegation of French workers to visit London during the Exhibition of 1862, thus giving them the chance to establish contact with men such as George Odger, secretary of the Trades Council. When several of these representatives returned to London for a rally in July 1863 to mark the Polish insurrection, Odger wrote an Address to the Workmen of France from the Working Men of England', proposing that they should formalise their cross-Channel solidarity.

(2) The Spectator (19th February 1870)

Mr Odger has lost his election for Southwark by a majority of 304 against him, the Tory, Colonel Beresford, having been returned. Sir Sydney Waterlow polled more than thirteen hundred votes fewer than Mr. Odger, but then he resigned shortly after two o'clock in favour of Mr. Odger, and it would seem that his supporters were so little willing to accept his resignation in that sense, that some of them at least voted for Colonel Beresford rather than support an artisan. Certainly, as far as we can judge, the retirement of Sir Sydney Waterlow hardly at all improved Mr. Odger's subsequent poll, but rather increased the distance between his poll and the Conservative's. Nevertheless the result is that, for the first time, a member of the artizan class has polled upwards of 4,500 votes, and a considerably greater number of votes than a most wealthy, respectable, and benevolent member of the middle-class, who, in this borough, had every advantage that local connection could give him. That alone should be a pledge to members of the operative class that if they steadily persevere in their attempts to break down the class-feeling which at present excludes them from the House of Commons, they will soon succeed, and have quite sufficient success to secure to the House of Commons a very adequate infusion of the poorest, but by no means the least acute and energetic, class of the English people.

(3) Henry James, Lippincott's Monthly Magazine (July 1877)

The element of the grotesque was very noticeable to me in the most striking collection of the shabbier English types that I had seen since I came to London. The occasion of my seeing them was the funeral of Mr. George Odger, which befell some four or five weeks before the Easter period. Mr. George Odger, it will be remembered, was an English radical agitator, of humble origin, who had distinguished himself by a perverse desire to get into Parliament. He exercised, I believe, the useful profession of shoemaker, and he knocked in vain at the door that opens but to golden keys. But he was a useful and honorable man, and his own people gave him an honorable burial. I emerged accidentally into Piccadilly at the moment they were so engaged, and the spectacle was one I should have been sorry to miss. The crowd was enormous, but I managed to squeeze through it and to get into a hansom cab that was drawn up beside the pavement, and here I looked on as from a box at a play. Though it was a funeral that was going on I will not call it a tragedy; but it was a very serious comedy. The day happened to be magnificent - the finest of the year. The funeral had been taken in hand by the classes who are socially unrepresented in Parliament, and it had the character of a great popular "manifestation." The hearse was followed by very few carriages, but the cortege of pedestrians stretched away in the sunshine, up and down the classic gentility of Piccadilly, on a scale that was highly impressive. Here and there the line was broken by a small brass band - apparently one of those bands of itinerant Germans that play for coppers beneath lodginghouse windows; but for the rest it was compactly made up of

what the newspapers call the dregs of the population. It was the London rabble, the metropolitan mob, men and women, boys and girls, the decent poor and the indecent, who had scrambled into the ranks as they gathered them up on their passage, and were making a sort of solemn spree of it.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)