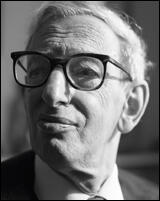

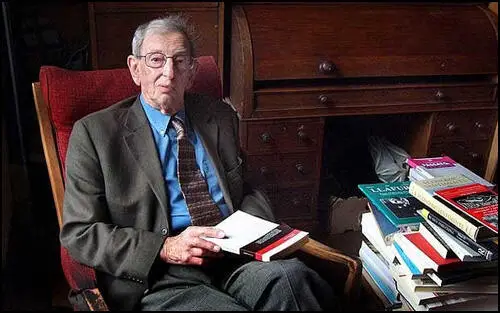

Eric Hobsbawm

Eric Hobsbawm, the elder child of Leopold Percy Hobsbawm, formerly Obstbaum, general merchant, and his wife, Nelly Grün Hobsbawm, was born on 9th June 1917 in Alexandria, Egypt. His grandfather, who was a cabinet-maker in Poland, came to London in the 1870s. Leopold, Eric's father, was one of eight children, all of whom were born in Britain and took British citizenship. (1)

In 1913 Leopold, who was then working in Alexandria for an Egyptian shipping office, met Eric's mother, Nelly Grün, the daughter of a "moderately prosperous Viennese jeweller". They married in neutral Switzerland in 1915, but were unable to live in either country until the First World War ended. (2)

In 1919, the family, which was Jewish, settled in Vienna, where Hobsbawm went to elementary school. "At the time playing and learning, family and school defined my life, as they defined the lives of most Viennese children in the 1920s. Virtually everything we experienced came to us in these ways or fitted into one or other of these frameworks. Of the two networks which constituted most of my life, the family was the far the more permanent." (3)

According to Martin Jacques: "The circumstances of Hobsbawm's childhood and early teens were to leave an indelible imprint on the rest of his life. A middle-class family that lived precariously - in a city and country that lived equally precariously - was always on the brink, his father seemingly incapable of holding down a steady job or delivering a secure income. Increasingly the family lived from hand to mouth, dependent on the support of relatives." (4)

In 1929 his father died suddenly of a heart attack. Two years later his mother died of tuberculosis. Hobsbawm later claimed that the two deaths were connected. "In the late evening of Friday 8th February 1929 my father returned from another of his increasingly desperate visits to town in search of money to earn or borrow, and collapsed outside the front door of our house. My mother heard his groans through the upstairs window and, when she opened them on the freezing air of that spectacularly hard alpine winter, she heard him calling to her. Within a few minutes he was dead, I assume from a heart attack. He was forty-eight years old. In dying, he also condemned to death my mother, who could not forgive herself for the way she felt she had treated him in what turned out to be the last terrible months, indeed the very last days, of his life…Within two and a half years she was dead also, at the age of thirty-six. I have always assumed that her many self-lacerating, underdressed visits to his grave in the harsh winter months after his death contributed to the lung disease which killed her." (5)

German Communist Party

Hobsbawm was only 14, and his uncle took him and his sister Nancy to live in Berlin. As a teenager in the Weimar Republic he inescapably became politicised. He read Karl Marx for the first time and told his school teacher he was now a communist. (6) Hobsbawm joined the Sozialistischer Schulerbund (Socialist Schoolboys). He argued: "It was impossible to remain outside politics. The months in Berlin made me a lifelong communist." (7)

Hobsbawm saw the dangers of Adolf Hitler taking power. By this time he believed the Russian Revolution was "the great hope of the world". (8) Not long before his death he reflected: "Anybody who saw Hitler's rise happen first-hand could not have helped but be shaped by it, politically. That boy is still somewhere inside, always will be." On 25 January 1933 Hobsbawm took part in the KPD organized last legal demonstration. (9)

As a member of a Communist student organization, he slipped party fliers under apartment doors in the weeks after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor and at one point concealed an illegal duplicating machine under his bed. (10) Hobsbawm took part in the German Communist Party last legal demonstration on 25th January 1933. Five days later Hitler was appointed chancellor. (11)

Hobsbawm admitted: "In Germany there wasn't any alternative left. Liberalism was failing. If I'd been German and not a Jew, I could see I might have become a Nazi, a German nationalist. I could see how they'd become passionate about saving the nation. It was a time when you didn't believe there was a future unless the world was fundamentally transformed." (12)

Hobsbawm took part in the March 1933 General Election campaign. "It was also my introduction to a characteristic experience of the communist movement: doing something hopeless and dangerous because the Party told us to. True, we might have wanted to help in the campaign in any case, but, given the situation, we did what we did as a gesture of our devotion to communism, that is to say to the Party. Much in the way that I, finding myself alone in the tram with two SA men, and justifiably scared, refused to conceal or take off my badge. We would go into the apartment buildings and, starting on the top floor, push the leaflets into each flat for signs of danger… Distributing election appeals for the KPD was no laughing manner, especially in the days after the Reichstag fire. Nor was voting for it, although over 13 per cent of the electorate still did so on 5 March. We had a right to be scared, for we were risking not only our own skins, but our parents". (13)

In April his Uncle Sidney and Aunt Gretl left Berlin for England taking with them the two young Hobsbawms. (14) Hobsbawm later recalled: "The months in Berlin made me a lifelong communist, or at least a man whose life would lose its nature and its significance without the political project to which he committed himself as a schoolboy, even though that project has demonstrably failed, and as I now know, was bound to fail. The dream of the October Revolution is still there somewhere inside me, as deleted texts are still waiting to be recovered by experts, somewhere on the hard disks of computers. I have abandoned, nay rejected it, but it has not been obliterated." (15)

Cambridge University

In April his Uncle Sidney and Aunt Gretl left Berlin for England taking with them the two young Hobsbawms. He was forbidden by his uncle to join either the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) or the Labour Party and told to concentrate on his studies. (16) The Hobsbawms went to live in Edgware in 1934. At the time he did not speak English but this was "not a problem" because the English education system was "way behind" the German. (17)

He became a pupil at Marylebone Grammar School where he came under the influence of Harold Llewellyn-Smith, "a handsome, well-connected, never married pillar of the Liberal Party, son of the architect of the Labour policy of Edwardian and Georgian Britain and a good part of the welfare state, who taught me history, steered me into Oxbridge, and eventually became headmaster of the school himself... Leaving aside the attraction of working with boys, it was the desire to do good works among the unprivileged. he lent me his books, mobilized his connections on my behalf, told me (correctly) how to handle the Oxbridge scholarship examinations, which colleges were the rights ones for me and warned me that I would there have to live like the rich, among gentlemen." (18)

During this period Hobsbawm developed a strong interest in modern jazz: "I experienced this musical revelation at the age of first love, sixteen or seventeen. But in my case it virtually replaced first love, for, ashamed of my looks and therefore convinced of being physically unattractive, I deliberately repressed my physical sensuality and sexual impulses. Jazz brought the dimension of wordless, unquestioning physical emotion into a life otherwise almost monopolized by words and the exercises of the exercises of the intellect. I did not then guess that in adult life my reputation as a jazz-lover would serve me well in unexpected ways. Then and for most of my lifetime a passion for jazz marked off a small and unusually embattled group even among the cultural minority tastes. For two-thirds of my life this passion bonded together the minority who shared it, into a sort of quasi-underground international freemasonry ready to introduce their country to those who came to them with the right code-sign." (19)

In 1936 Hobsbawm won a scholarship to King's College, Cambridge. While at university he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. He gained an enviable reputation for his intellectual prowess: "Is there anything that Hobsbawm doesn't know?' was a familiar refrain among his friends." (20)

On his arrival at university he wrote a description of himself: "A tall, angular, dangly, ugly, fair-haired fellow of eighteen and a half, quick on the uptake, with a considerable if superficial stock of general knowledge and a lot of original ideas, general and theoretical. An incorrigible striker of attitudes, which is all the more dangerous and at times effective, as he talks himself into believing in them himself. Not in love and apparently quite successful in sublimating his passions, which – not often – find expression in the ecstatic enjoyment of nature and art. Has no sense of morality, thoroughly selfish. Some people find him extremely disagreeable, others likeable, yet others (the majority) just ridiculous. He wants to be a revolutionary but, so far, shows no talent for organization. He wants to be a writer, but without energy and the ability to shape the material. He hasn't got the faith that will move the necessary mountains, only hope. He is vain and conceited. He is a coward. He loves nature deeply." (21)

Hobsbawm gained a double first in history, edited the student newspaper Granta, and was elected a member of the Apostles, an elitist society whose previous members included John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, Bertrand Russell, Roger Fry, Leonard Woolf and E. M. Forster. (22) Russell later commented: "It was owing to the existence of the Society that I soon got to know the people best worth knowing." (23)

Alec Cairncross has attempted to explain the beliefs of the Apostles: "The key difference in the attitude of Keynes and his friends was that the basis of the calculus of moral action was seen as exclusively personal, not as rules imposed from without. There could be no objective measure of what was good since, if the good consisted of states of mind, these states could be known and judged only by the minds in question. Duty, action, social need simply did not enter. Intuitive judgements were all one could turn to." (24)

The Second World War

On the outbreak of the Second World War Hobsbawm joined the British Army. Despite speaking German, French, Spanish and Italian fluently he was turned down for intelligence work. "The best way of summing up my personal experience of the Second World War is to say that it took six and a half years out of my life, six of them in the British army. I had neither a 'good war' not a 'bad war', but an empty war. I did nothing of significance in it, and was not asked to. Those were the least satisfactory years in my life." (25)

Hobsbawm served with the Royal Engineers and later with the Educational Corps. MI5 created a file on Hobsbawm in 1942. Although he was cleared of "suspicion of engaging in subversive activities or propaganda in the army", he was prevented from joining the Intelligence Corps by Roger Hollis, who later became head of MI5. At the end of the war, in July 1945, an MI5 officer noted: "As he is known to be in contact with communists I should be interested to see all his personal correspondence". (26)

On 12 May 1943 he married Muriel Seaman (1916–1963), whom he had met as an undergraduate at Cambridge University; she was the daughter of Alfred George Seaman, bank officer, and at the time of their marriage was working as a temporary civil servant at the Board of Trade. (27) Muriel was also a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain but it was not a happy marriage. According to a MI5 report Hobsbawm had “difficulties with his wife, who does not consider him to be a fervent enough Communist". (28)

Communist Party Historians' Group

In 1946 several historians who were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, that included Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, E. P. Thompson, Raphael Samuel, A. L. Morton, John Saville, George Rudé, Rodney Hilton, Dorothy Thompson, Dona Torr, Douglas Garman, Joan Browne, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan, Maurice Dobb, James B. Jefferys, John Morris and Allan Merson, formed the Communist Party Historians' Group. (29) Francis Beckett pointed out that these "were historians of a new type - socialists to whom history was not so much the doings of kings, queens and prime ministers, as those of the people." (30)

The group had been inspired by A. L. Morton's People's History of England (1938). Christopher Hill, the group's chairman, argued that the book provided a "broad framework" for the group's subsequent work in posing "an infinity of questions to think about"; for Eric Hobsbawm, it would become a model in how to write searching but accessible history, whereas for Raphael Samuel, who first encountered the book as a schoolboy, it was an antidote to "reactionary" history from above. According to Ben Harker: "Morton was an inspiration for a rising generation of Marxist historians who would come to dominate their respective fields." (31)

At their first meeting on 26th October 1946, Christopher Hill suggested that the Group was divided into period subgroups, i.e. ancient, medieval, sixteenth-seventeenth centuries and the nineteenth century. The first committee was comprised of Hill as chairman and Eric Hobsbawm as treasurer. Other members of the committee included Douglas Garman, Joan Browne, John Morris and Allan Merson. Later the Communist Party Historians' Group formed a school teachers group. (32)

Eric Hobsbawm later explained: "From 1946 to 1956 we – a group of comrades and friends – conducted a continuous Marxist seminar for our selves in the Historians' Group of the Communist Party, by means of endless duplicated discussion papers and regular meetings, mainly in the upper room of the Garibaldi Restaurant in Saffron Hill and occasionally in the then shabby premises of Marx House on Clerkenwell Green… Perhaps this was where we really became historians." (33) Hans-Ulrich Wehler has pointed out that "the astonishing impact of this generation of Marist historians" without whom "the worldwide influence of British historical scholarship, especially since the 1960s, is inconceivable." (34)

John Saville argued in his book, Memoirs from the Left (2003) that Hill's publication of his pamphlet, The English Revolution: 1640 (1940) was an important factor in the formation of the group: "We all regarded him as the senior member of the Historian's group, a historian of growing reputation and a man of notable integrity: characteristics which remained throughout his life." (35)

The CPHG expanded its work to local branches in Manchester, Nottingham and Sheffield, holding conferences, and producing a bulletin of local history in 1951. What united the Group beyond political comradeship and friendship was its members' passion for history, especially their local history, and their attempt to enrich the "battle of ideas" against conservatism. (36) According to Christos Efstathiou: Their discussions were characterised by a high level of openness and encouragement of critical perspectives, but were also products of committed intellectuals who did not separate their academic and political objectives." (37)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that: "The main pillars of the Group thus consisted initially of people who had graduated sufficiently early in the 1930s to have done some research, to have begun to publish and, in very exceptional cases, to have begun to teach. Among these Christopher Hill already occupied a special position as the author of a major interpretation of the English Revolution and a link with Soviet economic historians." (38)

John Saville later recalled: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching. For me, it was a privilege I have always recognised and appreciated." (39)

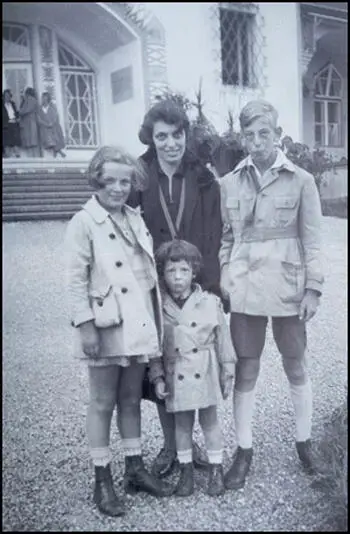

Guide, Christopher Hill, A. L. Morton, interpreter and Eric Hobsbawm (December, 1954)

Four members of the Communist Party Historians' Group: Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, A. L. Morton and Robert Browning, were invited by the Soviet Academy of Sciences to visit the Soviet Union during the academic Christmas vacation of 1954-55. Hobsbawm later recalled: "There were no telephone directories, no maps, no public timetables, no basic means of everyday reference. One was struck by the sheer impractically of a society in which an almost paranoiac fear of espionage turned the information needed for everyday life into a state secret. In short, there was not much to be learned about Russia by visiting it in 1954 that could not have been learned outside... I returned from Moscow politically unchanged if depressed, and without any desire to go there again." (40)

Past and Present

After the war Hobsbawm received a research studentship and in 1947 he was given a lectureship at Birkbeck College. In 1949 he was made a fellow of King's College, Cambridge, and for the next six years he divided his time between Cambridge and London. He completed his PhD on the Fabians and in 1948 he published his first book, Labour's Turning Point: 1880-1900, an edited collection of documents from the Fabian era. (41)

In January 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. According to his biographer, Christopher Hill was the prime mover of this venture. (42) Hobsbawm was appointed assistant editor. The editor was John Morris and members of the editorial board included:Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. H. M. Jones, Geoffrey Barraclough, Reginald Betts, Maurice Dobb, Vere G. Childe, and David B. Quinn. Its aim was to break the mould of traditional historical journals by introducing new ideas and approaches, not least those of the social sciences. In its opening number, it said: "We shall make a consistent attempt to widen the somewhat narrow horizon of traditional historical studies among the English-speaking public. The serious student in the mid-twentieth-century can no longer rest in ignorance of the history and historical thought of the greater part of the world." (43)

Hobsbawm later explained: "When some communist historians founded a new historical journal, Past and Present, in 1952, about as bad a time in the Cold War as can be imagined, we deliberately planned it not as a Marxist journal, but as a common platform for a "popular front" of historians, to be judged not by the badge in the author's ideological buttonhole, but by the contents of their articles. We desperately wanted to broaden the base of the editorial board, which at the start was naturally dominated by Party members, since only the rare, usually indigenous, radical historian with a safe academic base, such as A. H. M. Jones, the ancient historian from Cambridge, had the courage to sit at the same table as the Bolsheviks." (44)

Eventually the editors of the journal managed to persuade a group of non-Marxist historians of subsequent eminence, led by Lawrence Stone, and John Elliott, later Regius Professor at Oxford, who had sympathized with their objectives offered to join the board collectively on condition that they dropped the ideologically suspect phrase "a journal of scientific history" from its masthead. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (45)

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation Policy

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. (46)

In July 1956, two members of the Communist Party Historians' Group, E. P. Thompson and John Saville, starting publishing The New Reasoner as a forum for the discussion of "questions of fundamental principle, aim, and strategy," critiquing Stalinism as well as the dogmatic politics of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). It was open defiance of Party discipline to put out a publication not sanctioned by Party headquarters. As a result both Thompson and Saville were suspended from the CPGB. (47)

In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar. (48)

Most members of the Communist Party Historians' Group, supported Imre Nagy and as a result, like most Marxists, left the Communist Party of Great Britain after the Hungarian Uprising and a "New Left movement seemed to emerge, united under the banners of socialist humanism... the New Leftists aimed to renew this spirit by trying to organise a new democratic-leftist coalition, which in their minds would both counter the 'bipolar system' of the cold war and preserve the best cultural legacies of the British people." (49)

As John Saville pointed out: "I still regard it as wonderfully fortunate that I was of the generation that established the Communist Historians' group. For ten years we exchanged ideas and developed our Marxism into what we hoped were creative channels. It was not chance that when the secret speech of Khrushchev was made known in the West, it was members of the historians' group who were among the most active of the Party intellectuals on demanding a full discussion and uninhibited debate." (50)

Francis Beckett, the author of Enemy Within: The Rise and Fall of the British Communist Party (1995) argues that those who left were a greater lost of the CPGB than its leaders could ever bring themselves to admit. (51) Over 7,000 members of the CPGB resigned over what happened in Hungary. One of them, Peter Fryer, later recalled: "The central issue is the elimination of what has come to be known as Stalinism. Stalin is dead, but the men he trained in methods of odious political immorality still control the destinies of States and Communist Parties. The Soviet aggression in Hungary marked the obstinate re-emergence of Stalinism in Soviet policy, and undid much of the good work towards easing international tension that had been done in the preceding three years. By supporting this aggression the leaders of the British Party proved themselves unrepentant Stalinists, hostile in the main to the process of democratisation in Eastern Europe. They must be fought as such." (52)

However, Eric Hobsbawm did not leave the Communist Party of Great Britain. It is often assumed that his opposition to the Soviet Union invasion of Hungary was perhaps milder than other members of the Communist Party Historians' Group. This was not the case. On 12th November, 1956, Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill and Doris Lessing agreed to write a letter to the party’s paper, The Daily Worker, attacking the party leadership’s attitude towards the crimes of the Soviet Union. (53)

The letter stated: "All of us have for many years advocated Marxist ideas both in our special fields and in political discussion in the Labour movement. We feel therefore that we have a responsibility to express our views as Marxists in the present crisis of international socialism. We feel that the uncritical support given by the Executive Committee of the Communist Party to the Soviet action in Hungary is the undesirable culmination of years of distortion of fact, and failure by British Communists to think out political problems for themselves. We had hoped that the revelations made at the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union would have made our leadership and press realise that Marxist ideas will only be acceptable in the British Labour movement if they arise from the truth about the world we live in. The exposure of grave crimes and abuses in the USSR and the recent revolt of workers and intellectuals against the pseudo-Communist bureaucracies and police systems of Poland and Hungary, have shown that for the past twelve years we have based our political analyses on a false presentation of the facts - not an out-of-date theory, for we still consider the Marxist method to be correct." (54)

Hobsbawm later explained in his autobiography, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002): "Though I remained in the CP, unlike most of my friends in the Historians' Group, my situation as a man cut loose from his political moorings was not substantially different from theirs. In any case my relations with them remained the same.... Party membership no longer meant to me what it had since 1933. In practice I recycled myself from militant to sympathizer or fellow-traveller, or, to put it another way, from effective membership of the British Communist Party to something like spiritual membership of the Italian CP, which fitted my ideas of communism rather better." (55)

Tristram Hunt has suggested that by staying in the Communist Party he appeared to be a supporter of Joseph Stalin. He replied: "I wasn't a Stalinist. I criticised Stalin and I cannot conceive how what I've written can be regarded as a defence of Stalin... Why I stayed in the Communist Party is not a political question about communism, it's a one-off biographical question. It wasn't out of idealisation of the October Revolution. I'm not an idealiser. One should not delude oneself about the people or things one cares most about in one's life. Communism is one of these things and I've done my best not to delude myself about it even though I was loyal to it and to its memory. The phenomenon of communism and the passion it aroused is specific to the twentieth century. It was a combination of the great hopes which were brought with progress and the belief in human improvement during the nineteenth century along with the discovery that the bourgeois society in which we live (however great and successful) did not work and at certain stages looked as though it was on the verge of collapse. And it did collapse and generated awful nightmares." (56)

Eric Hobsbawm - Historian

Hobsbawm published his first major work, Primitive Rebels, a highly original account of southern European rural secret societies and millenarian cultures. He returned to these themes a decade later in Captain Swing (1969), a study of rural protest in early nineteenth-century England, with George Rudé, and most notably in Bandits (1969), which was over time to spawn a huge literature on the subject. Martin Jacques has argued "It is not difficult from this thread of his writing to see why Hobsbawm later said that if he had not been an historian he would like to have been an anthropologist." In 1964 he published Labouring Men, a collection of essays on the history of labour, including one on the standard of living debate in the first half of the nineteenth century. The book served to establish his pre-eminence in the scholarly history of the British working classes. (57)

Hobsbawm explained in his autobiography, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002) that he was trying to do "historic justice to social struggles - banditry, millenennial sects, pre-industrial city rioters - that had been overlooked or even dismissed just because they tried to come to grips with the problems rebels of the poor in a new capitalist society with historically obsolete or inadequate equipment." Hobsbawm had been told by an academic from the University of California, "the epicentre of the US student eruption, that the more intellectual young rebels there read the book with great enthusiasm because they identified themselves and the movement with my rebels." (58)

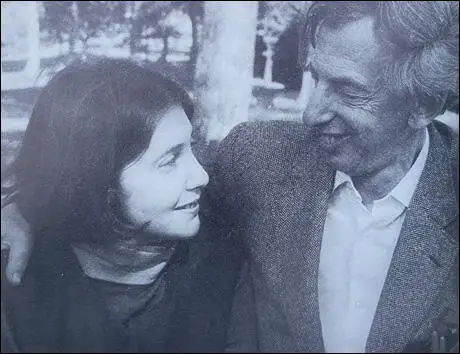

Hobsbawm's first marriage was unhappy, ending in divorce in 1951. In 1958 he had a son, Joshua Bennathan with Marion Bennathan, but the relationship did not last. "In 1962 he married Marlene Schwarz, with whom he was to form an extremely rich and rewarding partnership which lasted until his death, with many shared interests including travel, languages, music, entertaining, and party-going. Hobsbawm found a new kind of happiness and contentment and, with their two children, Andy (b. 1963) and Julia (b. 1964), a stable and loving family life that he had never experienced himself as a child and teenager. The Hobsbawms were great entertainers at their home in Nassington Road, Hampstead. Marlene was a wonderful host and Hobsbawm was highly convivial and stimulating company. Dinner there was enormously enjoyable and uplifting: there was never a dull moment, and ideas, stimulation, not to mention laughter, filled the air." (59)

Hobsbawm trilogy charting the rise of capitalism - The Age of Revolution (1962), The Age of Capital (1975) and The Age of Empire (1987) - became a defining work of his chosen period, the "long 19th century", from 1789 to 1914. "Encylopaedic and determinedly accessible, Hobsbawm has been credited with a hand in history's current popularity." Ben Pimlott, says his Marxism has been "a tool not a straitjacket; he's not dialectical or following a party line". According to Stuart Hall, he is one of few left wing historians to be "taken seriously by people who disagree with him politically". (60)

Hobsbawm's book, Industry and Empire (1968), a study of Britain from 1750 to the late twentieth century, proved highly influential and brought his writing to the attention of a much wider audience. Hobsbawm believed that as an historian he should stick clear of the events of his own lifetime. But the events of the late twentieth century persuaded him otherwise. The Age of Extremes: the Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991 was published in 1994. "Arguably it was the most successful of them all: it was translated into thirty-seven languages within the first year of its publication." (61)

Although he remained a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain until is dissolved in 1991 he took a keen interest in the Labour Party. Hobsbawm was deeply hostile to the attempt by the left to take over the party in during the 1980s and became a strong supporter of the attempts by Neil Kinnock to reform the Labour Party. Kinnock publicly acknowledged his debt to Hobsbawm and allowed himself to be interviewed by the man he described as as "my favourite Marxist". (62) Hobsbawm delivered a lecture at a Fabian Society event where he criticised Tony Benn, who was a strong advocate of socialism. He began his talk by saying that "the Bennite left reminded him of the man who lost his pipe on Hampstead Heath but preferred to search for it in his living room because the light was much better there." (63)

Tristram Hunt asked Hobsbawm about this surprising support of Kinnock: "To the fury of your comrades you became a committed supporter of Neil Kinnock's modernisation of the party - describing the 1992 general election night as the 'saddest and most desperate in my political experience'. Yet you have spoken out against Tony Blair, branding him 'Thatcher in trousers'. Surely New Labour was the inevitable conclusion of Kinnock's modernisation process?" Hobsbawm replied that he thought that the reforms put forward by Neil Kinnock would make the Labour Party more electable. However, he believed that Tony Blair had made too many changes to the party: "What we thought of was a reformed Labour Party not a simple rejection of everything that Labour had stood for. Obviously, any Labour Government, however watered down, is better than the right-wing alternative as the USA demonstrates. But I'm not absolutely certain that Labour Prime Ministers who glory in trying to be warlords - subordinate warlords particularly - are a thing that I can stick and it certainly sticks in my gullet." (64)

Although he never joined the Labour Party he once stated: "If there was anything to be done in this country we knew it would be through the Labour party". (65) Hobsbawm has been criticised as being a "champagne socialist". Although he was a Marxist he did well out of capitalism and was accused of being a hypocrite. The author Claire Tomalin, recalled asking Hobsbawm how, as a communist, he could live in such a splendid house in Hampstead. He replied that "if you're in a ship that's going down you might as well travel first class". (66)

Other book by Hobsbawm included Revolutionaries (1973), History of Marxism (1978), Workers (1984), Nations and Nationalism (1990), On History (1997), Uncommon People (1998), The New Century (1999), Interesting Times (2002) and Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism (2008). Martin Jacques has argued: "Hobsbawm's breadth of knowledge was combined with his incomparable ability to synthesize. He could make connections, see patterns, discern trends, and draw big pictures in a way that was far beyond the capacity of other historians, and in doing so was able enormously to enhance our understanding of historical events and processes. He was also possessed of an acutely analytical mind: he could reduce problems and questions to their essence, could invariably see the wood and not be distracted by the trees, even if he knew the names of all the trees. It is not difficult here to see the vital role that Marxism played in his historical work and its appeal for him: the importance of interconnections, the ability to synthesize, the multi-disciplinary approach, the power of analysis. There was nothing arid or dogmatic or abstract about his Marxism: on the contrary, his work was always surprising, his conclusions never predictable, the role of contingency always respected." (67)

Eric Hobsbawm died aged 95 on 1st October, 2012.

Primary Sources

(1) Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

In the late evening of Friday 8 February 1929 my father returned from another of his increasingly desperate visits to town in search of money to earn or borrow, and collapsed outside the front door of our house. My mother heard his groans through the upstairs window and, when she opened them on the freezing air of that spectacularly hard alpine winter, she heard him calling to her. Within a few minutes he was dead, I assume from a heart attack. He was forty-eight years old. In dying, he also condemned to death my mother, who could not forgive herself for the way she felt she had treated him in what turned out to be the last terrible months, indeed the very last days, of his life…

Within two and a half years she was dead also, at the age of thirty-six. I have always assumed that her many self-lacerating, underdressed visits to his grave in the harsh winter months after his death contributed to the lung disease which killed her.

(2) Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

The months in Berlin made me a lifelong communist, or at least a man whose life would lose its nature and its significance without the political project to which he committed himself as a schoolboy, even though that project has demonstrably failed, and as I now know, was bound to fail. The dream of the October Revolution is still there somewhere inside me, as deleted texts are still waiting to be recovered by experts, somewhere on the hard disks of computers. I have abandoned, nay rejected it, but it has not been obliterated.

(3) Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

I suppose taking part in that campaign (March 1933) was the first piece of genuinely political work I did. It was also my introduction to a characteristic experience of the communist movement: doing something hopeless and dangerous because the Party told us to. True, we might have wanted to help in the campaign in any case, but, given the situation, we did what we did as a gesture of our devotion to communism, that is to say to the Party. Much in the way that I, finding myself alone in the tram with two SA men, and justifiably scared, refused to conceal or take off my badge. We would go into the apartment buildings and, starting on the top floor, push the leaflets into each flat for signs of danger. There was an element of playing at the Wild West in this – we were the Indians rather than the US cavalry – but there was enough real danger to make us feel genuine fear as well as the thrill of risk-taking… Distributing election appeals for the KPD was no laughing manner, especially in the days after the Reichstag fire. Nor was voting for it, although over 13 per cent of the electorate still did so on 5 March. We had a right to be scared, for we were risking not only our own skins, but our parents'.

On 25 January 1933 the KPD organized its last legal demonstration, a mass march through the dark hours of Berlin converging on the headquarters of the Party, the Karl Liebknechthaus on the Bülowplatz (now Rosa Luxemburg-Platz), in response to a provocative mass parade of the SA on the same square. I took part in this march, presumably with other comrades from the SSB, although I have no specific memory of them.

Next to sex, the activity combining bodily experience and intense emotion to the highest degree is the participation in a mass demonstration at a time of great public exultation. Unlike sex, which is essentially individual, it is by its nature collective, and unlike the sexual climax, at any rate for men, it can be prolonged for hours. On the other hand, like sex it implies some physical action - marching, chanting slogans, singing – through which the merger of the individual in the mass, which is the essence of the collective experience, finds expression. The occasion has remained unforgettable, although I can recall no details of the demonstration…. What I can remember is singing, with intervals of heavy silence… We belonged together. I returned home to Halensee as if in a trance. When, in British isolation two years later, I reflected on the basis of my communism, this sense of "mass ecstasy" was one of the five components of it – together with pity for the exploited, the aesthetical appeal of a perfect and comprehensive intellectual system, "dialectical materialism", a little bit of the Blakean vision of the new Jerusalem and a good deal of intellectual anti-philistinism.

(4) Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

I experienced this musical revelation (a love of jazz) at the age of first love, sixteen or seventeen. But in my case it virtually replaced first love, for, ashamed of my looks and therefore convinced of being physically unattractive, I deliberately repressed my physical sensuality and sexual impulses. Jazz brought the dimension of wordless, unquestioning physical emotion into a life otherwise almost monopolized by words and the exercises of the exercises of the intellect.

I did not then guess that in adult life my reputation as a jazz-lover would serve me well in unexpected ways. Then and for most of my lifetime a passion for jazz marked off a small and unusually embattled group even among the cultural minority tastes. For two-thirds of my life this passion bonded together the minority who shared it, into a sort of quasi-underground international freemasonry ready to introduce their country to those who came to them with the right code-sign.

(5) Eric Hobsbawm, description of himself in 1936 that appeared him in Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm, a tall, angular, dangly, ugly, fair-haired fellow of eighteen and a half, quick on the uptake, with a considerable if superficial stock of general knowledge and a lot of original ideas, general and theoretical. An incorrigible striker of attitudes, which is all the more dangerous and at times effective, as he talks himself into believing in them himself. Not in love and apparently quite successful in sublimating his passions, which – not often – find expression in the ecstatic enjoyment of nature and art. Has no sense of morality, thoroughly selfish. Some people find him extremely disagreeable, others likeable, yet others (the majority) just ridiculous. He wants to be a revolutionary but, so far, shows no talent for organization. He wants to be a writer, but without energy and the ability to shape the material. He hasn't got the faith that will move the necessary mountains, only hope. He is vain and conceited. He is a coward. He loves nature deeply. And he forgets the German language.

(6) Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

From 1946 to 1956 we – a group of comrades and friends – conducted a continuous Marxist seminar for our selves in the Historians' Group of the Communist Party, by means of endless duplicated discussion papers and regular meetings, mainly in the upper room of the Garibaldi Restaurant in Saffron Hill and occasionally in the then shabby premises of Marx House on Clerkenwell Green… Perhaps this was where we really became historians. Others have spoken of "the astonishing impact of this generation of Marist historians" without whom "the worldwide influence of British historical scholarship, especially since the 1960s, is inconceivable." Among other things it gave birth to a successful and eventually influential historical journal in 1953, but Past and Present was born not in Clerkenwell, but in the more agreeable ambience of University College, Gower Street.

The Historians' Group broke up in the year of communist crisis, 1956. Until then we, and certainly I, had remained loyal, disciplined and politically aligned Communist Party members, helped no doubt by the wild rhetoric of crusading anti-communism of the "Free World". But it was far from easy.

(7) Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Life (2002)

When some communist historians founded a new historical journal, Past and Present, in 1952, about as bad a time in the Cold War as can be imagined, we deliberately planned it not as a Marxist journal, but as a common platform for a "popular front" of historians, to be judged not by the badge in the author's ideological buttonhole, but by the contents of their articles. We desperately wanted to broaden the base of the editorial board, which at the start was naturally dominated by Party members, since only the rare, usually indigenous, radical historian with a safe academic base, such as A. H. M. Jones, the ancient historian from Cambridge, had the courage to sit at the same table as the Bolsheviks…

We were equally keen to extend the range of our contributors. For several years we failed in the first task, although, thanks to our excellent reputation amo0ng younger academics, we soon did better on the second. In 1958 we succeeded. A group of non-Marxist historians of subsequent eminence, led by Lawrence Stone, shortly about to go to Princeton, and the present Sir John Elliott, later Regius Professor at Oxford, who had sympathized with our objectives but until then had found it impossible formally to join the former red establishment, offered to join us collectively on condition that we dropped the ideologically suspect phrase "a journal of scientific history" from our masthead. It was a cheap price to pay. They did not ask us about our political opinions – actually orthodox communists were no longer easy to find on the board – we did not enquire into theirs, and no ideological problems have ever arisen on its board since then. Even the Institute of Historical Research, which had steadfastly refused to include the journal in its library, relented.

(8) Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill and Doris Lessing, non-published letter to The Daily Worker (12th November, 1956)

All of us have for many years advocated Marxist ideas both in our special fields and in political discussion in the Labour movement. We feel therefore that we have a responsibility to express our views as Marxists in the present crisis of international socialism.

We feel that the uncritical support given by the Executive Committee of the Communist Party to the Soviet action in Hungary is the undesirable culmination of years of distortion of fact, and failure by British Communists to think out political problems for themselves. We had hoped that the revelations made at the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union would have made our leadership and press realise that Marxist ideas will only be acceptable in the British Labour movement if they arise from the truth about the world we live in.

The exposure of grave crimes and abuses in the USSR and the recent revolt of workers and intellectuals against the pseudo-Communist bureaucracies and police systems of Poland and Hungary, have shown that for the past twelve years we have based our political analyses on a false presentation of the facts - not an out-of-date theory, for we still consider the Marxist method to be correct.

If the left-wing and Marxist trend in our Labour movement is to win support, as it must for the achievement of socialism, this past must be utterly repudiated. This includes the repudiation of the latest outcome of the evil past, the Executive Committee's underwriting of the current errors of Soviet policy.

(9) Eric Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire (1968)

The Industrial Revolution marks the most fundamental transformation of human life in the history of the world recorded in written documents. For a brief period it coincided with the history of a single country, Great Britain. An entire world economy was thus built on, or rather around, Britain, and this country therefore temporarily rose to a position of global influence and power unparalleled by any state of its relative size before or since, and unlikely to be paralleled by any state in the foreseeable future. There was a moment in the world's history when Britain can be described, if we are not too pedantic, as its only workshop, its only massive importer and exporter, its only carrier, its only imperialist, almost its only foreign investor; and for that reason its only naval power and the only one which had a genuine world policy. Much of this monopoly was simply due to the loneliness of the pioneer, monarch of all he surveys because of the absence of any other surveyors. When other countries industrialized, it ended automatically, though the apparatus of world economic transfers constructed by, and in terms of, Britain remained indispensable to the rest of the world for a while longer. Nevertheless, for most of the world the 'British' era of industrialization was merely a phase - the initial, or an early phase of contemporary history. For Britain it was obviously much more than this. We have been profoundly marked by the experience of our economic and social pioneering and remain marked by it to this day.

(10) Eric Hobsbawm was interviewed by Tristram Hunt in The Observer (22nd September, 2002)

Tristram Hunt: Martin Amis's new book, Koba The Dread, has impugned the British Left - and you personally - for not condemning Stalin's atrocities. In your autobiography you vividly bring out the mind set of a believing Communist in the 1940s and 1950s: the party discipline and a reluctance "to believe the few who told us what they knew" of Soviet Russia. Yet you also bring out the historical context for joining the Communist Party - the battle against fascism on the streets of 1930s Berlin and a strong sense of the idealism of the October Revolution. There also remains the broader historical context that the Soviet Union remained a viable economic and political model to many in the West right up to the 1970s. Do you think this historical context seems absent in the current debate about "Communist guilt"?

Eric Hobsbawm: I must leave the discussion of Amis's views on Stalin to others. I wasn't a Stalinist. I criticised Stalin and I cannot conceive how what I've written can be regarded as a defence of Stalin. But as someone who was a loyal Party member for two decades before 1956 and therefore silent about a number of things about which it's reasonable not to be silent - things I knew or suspected in the USSR - I don't want to be critical of a book which brings out some of the horrors of Stalin. It isn't an original or important book. It brings nothing that we haven't known except perhaps about his personal relations with his father. But I don't want to say anything that might suggest to people that I'm in some ways trying to defend the record of something which is indefensible.

Tristram Hunt: Amis has criticised those on the Left who deny any moral equivalence between Nazism and Communism because the latter committed atrocities in the cause of a higher social ideal as opposed to racial genocide. The majority of deaths in the Soviet Union came not from political or racial persecution but famine caused by economic policies. As you have written of Stalin: 'His terrifying career makes no sense except as a stubborn, unbroken pursuit of that utopian aim of a communist society.' I want to tease out this issue of idealism. You stayed in the party after 1956 partly because of solidarity to the fallen and partly because of a belief in a societal ideal. Are you still drawn to an Enlightenment ideal of societal perfectibility or have you come to accept the limits of the human condition - what your friend Isaiah Berlin called, 'the crooked timber of humanity'?

Eric Hobsbawm: Why I stayed in the Communist Party is not a political question about communism, it's a one-off biographical question. It wasn't out of idealisation of the October Revolution. I'm not an idealiser. One should not delude oneself about the people or things one cares most about in one's life. Communism is one of these things and I've done my best not to delude myself about it even though I was loyal to it and to its memory. The phenomenon of communism and the passion it aroused is specific to the twentieth century. It was a combination of the great hopes which were brought with progress and the belief in human improvement during the nineteenth century along with the discovery that the bourgeois society in which we live (however great and successful) did not work and at certain stages looked as though it was on the verge of collapse. And it did collapse and generated awful nightmares.

Tristram Hunt: What struck me in your autobiography was that despite your lifelong Communist Party membership, you were deeply hostile to Militant Tendency attempts to take over the Labour Party during the 1980s. Indeed, to the fury of your comrades you became a committed supporter of Neil Kinnock's modernisation of the party - describing the 1992 general election night as the 'saddest and most desperate in my political experience'. Yet you have spoken out against Tony Blair, branding him "Thatcher in trousers". Surely New Labour was the inevitable conclusion of Kinnock's modernisation process?

Eric Hobsbawm: Most communists and indeed most socialists disagreed at the time (1980s) with the few of us who said it's absolutely no use, the Labour Party has got to go in a different direction. On the other hand, what we thought of was a reformed Labour Party not a simple rejection of everything that Labour had stood for. Obviously, any Labour Government, however watered down, is better than the right-wing alternative as the USA demonstrates. But I'm not absolutely certain that Labour Prime Ministers who glory in trying to be warlords - subordinate warlords particularly - are a thing that I can stick and it certainly sticks in my gullet.

(11) Maya Jaggi interviewed Eric Hobsbawm in the The Guardian (14th September, 2002)

Eric Hobsbawm was a schoolboy in Berlin when Hitler came to power. He knew he stood at a turning-point in history. "It was impossible to remain outside politics," he says. "The months in Berlin made me a lifelong communist." They may also have shaped his moral universe. When asked on Radio 4's Desert Island Discs in 1995 whether he thought the chance of bringing about a communist utopia was worth any sacrifice, he answered "yes". "Even the sacrifice of millions of lives?" he was asked. "That's what we felt when we fought the second world war," he replied.

Martin Amis in his new book Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million, discussing a perceived "asymmetry of indulgence" in attitudes towards Hitler's crimes and Stalin's Great Terror, characterises Hobsbawm's "yes" as "disgraceful". Interesting Times, Hobsbawm's autobiography, also out this month, offers an insight into the adherence to communism of many of the brightest of his generation, from an "unrepentant communist": Hobsbawm, who joined the party in 1936, remained in it until he let his membership lapse not long before the party's dissolution in 1991. His book - taking its title from the Chinese curse - traces his communist faith in "the most extraordinary and terrible century in human history".

"I've never tried to diminish the appalling things that happened in Russia, though the sheer extent of the massacres we didn't realise," says Hobsbawm."In the early days we knew a new world was being born amid blood and tears and horror: revolution, civil war, famine - we knew of the Volga famine of the early '20s, if not the early '30s. Thanks to the breakdown of the west, we had the illusion that even this brutal, experimental, system was going to work better than the west. It was that or nothing."

He says of Stalin's Russia: "These sacrifices were excessive; this should not have happened. In retrospect the project was doomed to failure, though it took a long time to realise this." Yet he appears to argue that some goals are worth any sacrifice. "I lived through the first world war, when 10 million-to 20 million people were killed. At the time, the British, French and Germans believed it was necessary. We disagree. In the second world war, 50 million died. Was the sacrifice worthwhile? I frankly cannot face the idea that it was not. I can't say it would have been better if the world was run by Adolph Hitler."

The Age of Extremes (1994), which was translated into 37 languages, extended Hobsbawm's range into the "short 20th century" almost spanned by his own life, from the first world war to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. He sees his autobiography as a "flipside" to The Age of Extremes, being world history "illustrated by the experiences of an individual". Interesting Times also reveals other sides to a man, who, under the pseudonym Francis Newton, was the New Statesman's jazz critic for a decade. His proudest moments were receiving an honorary degree beside Benny Goodman and meeting the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. He disparaged modernism in high art, when the "real revolution", he suggested, lay elsewhere, such as in the movies.

Now 85, and professor emeritus at Birkbeck College, London University, Hobsbawm lives in Hampstead, on the slopes of Parliament Hill, with his second wife, Marlene, a recently retired music teacher and writer. They also have a cottage in Wales "between the Hay-on-Wye literary festival and the Brecon jazz festival", where, according to the biographer Claire Tomalin, "they reproduce the urban intelligentsia in a Welsh wilderness". The couple have a "social circle of immense variety", says Roy Foster, a former colleague at Birkbeck. "Eric's a European intellectual; he doesn't allow ideology to infect the ordinary relations of life." While some find Hobsbawm cold and imperious, for Pimlott he has a great serenity.

Peripatetic as a displaced child then as an academic, Hobsbawm speaks German, French, Spanish and Italian fluently, and reads Dutch, Portuguese and Catalan. His reputation is arguably even greater abroad. Official recognition came slowly in Britain, where he was made a Companion of Honour in 1998. Hobsbawm insists that "whatever I've achieved has been with minimum, or no, concessions".

Hobsbawm was a member of the Communist party historians' group of 1946-56, which included EP Thompson and Christopher Hill, and in 1952 he co-founded the influential journal, Past and Present, whose contributors included many non-Marxists. They pioneered social history from the "bottom up". For Roy Foster, Hobsbawm "brought British social and labour history into an intellectually exciting and European-influenced sphere, bringing in culture from Romantic music to the role of the flat cap and fish and chips in working-class consciousness. At the same time he was writing about Sicilian bandits and Chicago gangsters." Unlike fellow British Marxist historians, Hobsbawm took an international approach, in such works as Industry and Empire (1968).

Hobsbawm's decision to stay in the party continues to puzzle even his sympathisers. Yet the writer and journalist Neal Ascherson, a student of his at Cambridge in the early 1950s who became a friend, recalls Hobsbawm being "in great distress and finding it difficult to talk... He said that you could achieve more by criticising from within." Hobsbawm signed a historians' letter of protest against the Soviet invasion of Hungary and was passionately in favour of the Prague spring, arguing against the "tankies" who backed its crushing by the Soviets in 1968. Yet he remained in the party, "recycling" himself from militant to fellow traveller, and resigning himself to interpreting the world, rather than actively changing it. Pimlott says Hobsbawm remained a member when it was deeply unfashionable and limiting; "he couldn't travel freely to the US. There was sacrifice in his position." Hobsbawm remained friends with many who did leave. Robin Blackburn, former editor of the New Left Review, for which he wrote, says, "I doubt he had many illusions about the Soviet Union after 1956; he was more hard-headed than many others."

In Paris in 1968, Hobsbawm found the events welcome "and puzzling to middle-aged left wingers". He was enthusiastic yet critical of the limitations of protests. "I misunderstood the historical significance of the 1960s," he says. "It wasn't a political or social revolution. It was more a spiritual equivalent of a consumer society - everybody doing their own thing. I'm not certain I welcome this." Another movement which some claim has eluded him is feminism. "His unwillingness to take seriously the research and concerns of women historians pissed off a whole generation of feminists in his profession in the '70s and '80s," says Harriet Jones, director of the Institute of Contemporary British History at London University. She senses a possible change of heart, however. "It's interesting that he has now identified women's history in the Communist party as one of the key gaps in 20th-century British politics."

Hobsbawm espoused Italian Eurocommunism, which distanced itself from Moscow (he found its late guru Gramsci "marvelously stimulating"). He also played a controversial role in the emergence of New Labour in Britain, having canvassed for the Labour party in 1945 ("If there was anything to be done in this country we knew it would be through the Labour party"). His Marx memorial lecture in 1978, The Forward March of Labour Halted? pointed to the inadequacy of Old Labour in the face of social and economic changes. Dubbed "Kinnock's guru", Hobsbawm has since criticised New Labour for going "much too far in accepting the logic of the free market", and been disparaged in turn as an out-of-touch "special intellectual" by the Number 10 adviser Geoff Mulgan, in 1998. Hobsbawm says: "While I share people's disappointment in Blair, it's better to have a Labour government than not."

(12) Martin Kettle and Dorothy Wedderburn, The Guardian (1st October 2012)

Had Eric Hobsbawm died 25 years ago, the obituaries would have described him as Britain's most distinguished Marxist historian and would have left it more or less there. Yet by the time of his death at the age of 95, he had achieved a unique position in the country's intellectual life. In his later years he became arguably Britain's most respected historian of any kind, recognised if not endorsed on the right as well as the left, and one of a tiny handful of historians of any era to enjoy genuine national and world renown.

Unlike some others, Hobsbawm achieved this wider recognition without in any major way revolting against either Marxism or Marx. In his 94th year he published How to Change the World, a vigorous defence of Marx's continuing relevance in the aftermath of the banking collapse of 2008-10. What is more, he achieved his culminating reputation at a time when the socialist ideas and projects that animated so much of his writing for well over half a century were in historic disarray, and worse – as he himself was always unflinchingly aware.

In a profession notorious for microscopic preoccupations, few historians have ever commanded such a wide field in such detail or with such authority. To the last, Hobsbawm considered himself to be essentially a 19th-century historian, but his sense of that and other centuries was both unprecedentedly broad and unusually cosmopolitan.

The sheer scope of his interest in the past, and his exceptional command of what he knew, continued to humble many, most of all in the four-volume Age of... series, in which he distilled the history of the capitalist world from 1789 to 1991. "Hobsbawm's capacity to store and retrieve detail has now reached a scale normally approached only by large archives with big staffs," wrote Neal Ascherson. Both in his knowledge of historic detail and in his extraordinary powers of synthesis, so well displayed in that four-volume project, he was unrivalled.

Hobsbawm was born in Alexandria, a good place for a historian of empire, in 1917, a good year for a communist. He was second-generation British, the grandson of a Polish Jew and cabinet-maker who came to London in the 1870s. Eight children, who included Leopold, Eric's father, were born in England and all took British citizenship at birth (Hobsbawm's Uncle Harry in due course became the first Labour mayor of Paddington).

But Eric was British of no ordinary background. Another uncle, Sidney, went to Egypt before the first world war and found a job there in a shipping office for Leopold. There, in 1914, Leopold Hobsbawm met Nelly Gruen, a young Viennese from a middle-class family who had been given a trip to Egypt as a prize for completing her school studies. The two got engaged, but the first world war broke out and they were separated. The couple eventually married in Switzerland in 1916, returning to Egypt for the birth of Eric, their first child.

"Every historian has his or her lifetime, a private perch from which to survey the world," he said in his 1993 Creighton lecture, one of several occasions in his later years when he attempted to relate his own lifetime to his own writing. "My own perch is constructed, among other materials, of a childhood in the Vienna of the 1920s, the years of Hitler's rise in Berlin, which determined my politics and my interest in history, and the England, and especially the Cambridge, of the 1930s, which confirmed both."

In 1919, the young family settled in Vienna, where Eric went to elementary school, a period he later recalled in a 1995 television documentary which featured pictures of a recognisably skinny young Viennese Hobsbawm in shorts and knee socks. Politics made their impact around this time. Eric's first political memory was in Vienna in 1927, when workers burned down the Palace of Justice. The first political conversation that he could recall took place in an Alpine sanatorium in these years, too. Two motherly Jewish women were discussing Leon Trotsky. "Say what you like," said one to the other, "but he's a Jewish boy called Bronstein."

In 1929 his father died suddenly of a heart attack. Two years later his mother died of TB. Eric was 14, and his Uncle Sidney took charge once more, taking Eric and his sister Nancy to live in Berlin. As a teenager in Weimar Republic Berlin, Eric inescapably became politicised. He read Marx for the first time, and became a communist.

He could always remember the day in January 1933 when, emerging from the Halensee S-Bahn station on his way home from his school, the celebrated Prinz Heinrich Gymnasium, he saw a newspaper headline announcing Hitler's election as chancellor. Around this time he joined the Socialist Schoolboys, which he described as "de facto part of the communist movement" and sold its publication, Schulkampf (School Struggle). He kept the organisation's duplicator under his bed and, if his later facility for writing was any guide, probably wrote most of the articles too. The family remained in Berlin until 1933, when Sidney Hobsbawm was posted by his employers to England.

The gangly teenage boy who settled with his sister in Edgware in 1934 described himself later as "completely continental and German speaking". School, though, was "not a problem" because the English education system was "way behind" the German. A cousin in Balham introduced him to jazz for the first time – the "unanswerable sound", he called it. The moment of conversion, he wrote some 60 years later, was when he first heard the Duke Ellington band "at its most imperial". He spent a period in the 1950s as jazz critic of the New Statesman, and published a Penguin Special, The Jazz Scene, on the subject in 1959 under the pen-name Francis Newton (many years later it was reissued with Hobsbawm identified as the author).

Learning to speak English properly, Eric became a pupil at Marylebone grammar school and in 1936 he won a scholarship to King's College, Cambridge. It was at this time that a saying became common among his Cambridge communist friends: "Is there anything that Hobsbawm doesn't know?" He became a member of the legendary Cambridge Apostles. "All of us thought that the crisis of the 1930s was the final crisis of capitalism," he wrote 40 years later. But, he added, "it was not."

When the second world war broke out, Hobsbawm volunteered, as many communists did, for intelligence work. But his politics, which were never a secret, led to rejection. Instead he became an improbable sapper in 560 Field Company, which he later described as "a very working-class unit trying to build some patently inadequate defences against invasion on the coasts of East Anglia". This, too, was a formative experience for the often aloof young intellectual prodigy. "There was something sublime about them and about Britain at that time," he wrote. "That wartime experience converted me to the British working class. They were not very clever, except for the Scots and Welsh, but they were very, very good people."

Hobsbawm married his first wife, Muriel Seaman, in 1943. After the war, returning to Cambridge, he made another choice, abandoning a planned doctorate on north African agrarian reform in favour of research on the Fabians. It was a move that opened the door to both a lifetime of study of the 19th century and an equally long-lasting preoccupation with the problems of the left. In 1947 he got his first tenured job, as a history lecturer at Birkbeck College, London, where he was to remain for much of his teaching life.

With the onset of the cold war, a very British academic McCarthyism meant that the Cambridge lectureship which Hobsbawm always coveted never materialised. He shuttled between Cambridge and London, one of the principal organisers and driving forces of the Communist Party Historians Group, a glittering radical academy which brought together some of the most prominent historians of the postwar era. Its members also included Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, AL Morton, EP Thompson, John Saville and, later, Raphael Samuel. Whatever else it achieved, the CP Historians Group, about which Hobsbawm wrote an authoritative essay in 1978, certainly provided a nucleus for many of his first steps as a major historical writer.

Hobsbawm's first book, Labour's Turning Point (1948), an edited collection of documents from the Fabian era, belongs firmly to this CP-dominated era, as does his engagement in the once celebrated "standard of living" debate about the economic consequences of the early industrial revolution, in which he and RM Hartwell traded arguments in successive numbers of the Economic History Review. The foundation of the Past and Present journal – now the most lasting, if fully independent, legacy of the Historians Group – also belongs to this period.

Hobsbawm was never to leave the Communist party and always thought of himself as part of an international communist movement. For many, this remained the insuperable obstacle to an embrace of his writing. Yet he always remained very much a licensed free-thinker within the party's ranks. Over Hungary in 1956, an event which split the CP and drove many intellectuals out of the party, he was a voice of protest who nevertheless remained.

Yet, as with his contemporary, Christopher Hill, who left the CP at this time, the political trauma of 1956 and the start of a lastingly happy second marriage combined in some way to trigger a sustained and fruitful period of historical writing that was to establish fame and reputation. In 1959 he published his first major work, Primitive Rebels, a strikingly original account, particularly for those times, of southern European rural secret societies and millenarian cultures (he was still writing about the subject as recently as 2011). He returned to these themes again a decade later in Captain Swing, a detailed study of rural protest in early 19th-century England co-authored with George Rudé, and Bandits, a more wide-ranging attempt at synthesis. These works are reminders that Hobsbawm was both a bridge between European and British historiography and a forerunner of the notable rise of the study of social history in post-1968 Britain.

By this time, though, Hobsbawm had already published the first of the works on which both his popular and academic reputations still rest. A collection of some of his most important essays, Labouring Men, appeared in 1964 (a second collection, Worlds of Labour, was to follow 20 years later). But it was Industry and Empire (1968), a compelling summation of much of his work on Britain and the industrial revolution, that achieved the highest esteem. It has rarely been out of print.

Even more influential in the long term was the Age of… series, which he began in 1962 with The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848. This was followed in 1975 by The Age of Capital: 1848-1875 and in 1987 by The Age of Empire: 1875-1914. A fourth volume, The Age of Extremes: 1914-91, more quirky and speculative but in some respects the most remarkable and admirable of all, extended the sequence in 1994.

The four volumes embodied all of Hobsbawm's best qualities – the sweep combined with the telling anecdote and statistical grasp, the attention to the nuance and significance of events and words, and above all, perhaps, the unrivalled powers of synthesis (nowhere better displayed than in a classic summary of mid-19th century capitalism on the very first page of the second volume). The books were not conceived as a tetralogy, but as they appeared, they acquired individual and cumulative classic status. They were an example, Hobsbawm wrote, of "what the French call 'haute vulgarisation'" (he did not mean this self-deprecatingly), and they became, in the words of one reviewer, "part of the mental furniture of educated Englishmen".

Hobsbawm's first marriage had collapsed in 1951. During the 1950s, he had another relationship which resulted in the birth of his first son, Joss Bennathan, but the boy's mother did not want to marry. In 1962 he married again, this time to Marlene Schwarz, of Austrian descent. They moved to Hampstead and bought a small second home in Wales. They had two children, Andrew and Julia.

In the 1970s, Hobsbawm's widening fame as a historian was accompanied by a growing reputation as a writer about his own times. Though he had a historian's respect for the Communist party's centralist discipline, his intellectual eminence gave him an independence that won the respect of communism's toughest critics, such as Isaiah Berlin. It also ensured him the considerable accolade that not one of his books was ever published in the Soviet Union. Thus armed and protected, he ranged fearlessly across the condition of the left, mostly in the pages of the CP's monthly, Marxism Today, the increasingly heterodox publication of which he became the house deity.

His conversations with the Italian communist – and now state president – Giorgio Napolitano date from these years, and were published as The Italian Road to Socialism. But his most influential political work centred on his increasing certainty that the European labour movement had ceased to be capable of bearing the transformational role assigned to it by earlier Marxists. These uncompromisingly revisionist articles were collected under the general heading The Forward March of Labour Halted.

By 1983, when Neil Kinnock became the leader of the Labour party at the depth of its electoral fortunes, Hobsbawm's influence had begun to extend far beyond the CP and deep into Labour itself. Kinnock publicly acknowledged his debt to Hobsbawm and allowed himself to be interviewed by the man he described as as "my favourite Marxist". Though he strongly disapproved of much of what later took shape as "New Labour", which he saw, among other things, as historically cowardly, he was without question the single most influential intellectual forerunner of Labour's increasingly iconoclastic 1990s revisionism.

His status was underlined in 1998, when Tony Blair made him a Companion of Honour, a few months after Hobsbawm celebrated his 80th birthday. In its citation, Downing Street said Hobsbawm continued to publish works that "address problems in history and politics that have re-emerged to disturb the complacency of Europe".

In his later years, Hobsbawm enjoyed widespread reputation and respect. His 80th and 90th birthday celebrations were attended by a Who's Who of left wing and liberal intellectual Britain. Throughout the late years, he continued to publish volumes of essays, including On History (1997) and Uncommon People (1998), works in which Dizzy Gillespie and Salvatore Giuliano sat naturally side by side in the index as testimony to the range of Hobsbawm's abiding curiosity. A highly successful autobiography, Interesting Times, followed in 2002, and Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism in 2007.

More famous in his extreme old age than probably at any other period of his life, he broadcast regularly, lectured widely and was a regular performer at the Hay literary festival, of which he became president at the age of 93, following the death of Lord Bingham of Cornhill. A fall in late 2010 severely reduced his mobility, but his intellect and willpower remained unvanquished, as did his social and cultural life, thanks to Marlene's efforts, love – and cooking.

That his writings continued to command such audiences at a time when his politics were in some ways so eclipsed was the kind of disjunction which exasperated right wingers, but it was a paradox on which the subtle judgment of this least complacent of intellects feasted. In his later years, he liked to quote EM Forster that he was "always standing at a slight angle to the universe". Whether the remark says more about Hobsbawm or about the universe was something that he enjoyed disputing, confident in the knowledge that it was in some senses a lesson for them both.

He is survived by Marlene and his three children, seven grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

(13) Richard Norton-Taylor, The Guardian (24th October 2014)

MI5 amassed hundreds of records on Eric Hobsbawm and Christopher Hill, two of Britain’s leading historians who were both once members of the Communist party, secret files have revealed.

The scholars were subjected to persistent surveillance for decades as MI5 and police special branch officers tapped and recorded their telephone calls, intercepted their private correspondence and monitored their contacts, the files show. Some of the surveillance gave MI5 more details about their targets’ personal lives than any threat to national security.

The files, released at the National Archives on Friday, reveal the extent to which MI5, including its most senior officers, secretly kept tabs on the personal and professional activities of communists and suspected communists, a task it began before the cold war. The papers also show that MI5 opened personal files on the popular Oxford historian AJP Taylor, the writer Iris Murdoch, and the moral philosopher Mary Warnock after they and Hill signed a letter supporting a march against the nuclear bomb in 1959....

Hobsbawm, who was refused access to his files when he asked to see them five years ago, died in 2012, and Hill died in 2009. Many passages, sometimes whole pages, of their files remain redacted and an entire file on Hobsbawm has been “temporarily retained”. The files include long lists of names and addresses of letters written by Hobsbawm and Hill.

They make clear that MI5 frequently read – or was sent – copies of as many as 10 letters a day. At the same time, its officers, or special branch officers, or their informants – one of whom was given the codename Ratcatcher – were secretly taking notes of their phone calls and meetings.

The files show that Hobsbawm, who became one of Britain’s most respected historians and was made a Companion of Honour by Tony Blair, first came to the notice of MI5 in 1942 when he and 38 colleagues were described as being “obvious members of the CPGB [the Communist party of Great Britain] on Merseyside”. He became number 211,764 on MI5’s index of personal files. Although he was cleared of "suspicion of engaging in subversive activities or propaganda in the army", MI5 noted it was doubtful that he would be suitable for the Intelligence Corps. Roger Hollis, later head of MI5, and Valentine Vivian, the deputy chief of MI6, prevented him from joining the Foreign Office’s political intelligence department.

At the end of the war, in July 1945, an MI5 officer noted: "As he is known to be in contact with communists I should be interested to see all his personal correspondence".