The Great Purge

On 23rd December 1930, Isaak Illich Rubin was arrested by the secret police and charged with participation in a plot to establish an underground organization called the "Union Bureau of Mensheviks." Rubin's sister later reported: "They put Rubin for days in the kartser, the punishment cell. My brother at forty-five was a man with a diseased heart and diseased joints. The kartser was a stone hole the size of a man; you couldn't move in it, you could only stand or sit on the stone floor. But my brother endured this torture too, and left the kartser with a feeling of inner confidence in himself, in his moral strength."

The OGPU now decided to change their tactics. On 28th January, 1931, he was taken to the cell of a prisoner named Vasil'evskii. The interrogator told the prisoner: "We are going to shoot you now, if Rubin does not confess." Vasil'evskii went on his knees and begged Rubin: "Isaac Il'ich, what does it cost you to confess?" According to his sister, "my brother remained firm and calm, even when they shot Vasil'evskii right there". The next night they took him to the cell of a prisoner called Dorodnov: "This time a young man who looked like a student was there. My brother didn't know him. When they turned to the student with the words, 'You will be shot because Rubin will not confess,' the student tore open his shirt at the breast and said, 'Fascists, gendarmes, shoot!' They shot him right there."

The killing of Dorodnov persuaded Rubin to confess to being a member of "Union Bureau of Mensheviks" and to implicate his friend and mentor, David Riazanov. Rubin's sister continued the story: "Rubin's position was tragic. He had to confess to what had never existed, and nothing had: neither his former views; nor his connections with the other defendants, most of whom he didn't even know, while others he knew only by chance; nor any documents that had supposedly been entrusted to his safekeeping; nor that sealed package of documents which he was supposed to have handed over to Riazanov. In the course of the interrogation and negotiations with the investigator, it became clear to Rubin that the name of Riazanov would figure in the whole affair, if not in Rubin's testimony, then in the testimony of someone else. And Rubin agreed to tell the whole story about the mythical package. My brother told me that speaking against Riazanov was just like speaking against his own father. That was the hardest part for him."

V. V. Sher was another witness who gave evidence against Riazanov. One of his friends, Victor Serge, argued in his book, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "Of course his heretical colleagues were often arrested, and he defended them, with all due discretion. He had access to all quarters and the leaders were a little afraid of his frank way of talking. His reputation had just been officially recognized in a celebration of his sixtieth birthday and his life's work when the arrest of the Menshevik sympathizer Sher, a neurotic intellectual who promptly made all the confessions that anyone pleased to dictate to him, put Riazanov beside himself with rage. Having learnt that a trial of old Socialists was being set in hand, with monstrously ridiculous confessions foisted on them, Riazanov flared up and told member after member of the Politburo that it was a dishonor to the regime, that all this organized frenzy simply did not stand up and that Sher was half-mad anyway."

Roy A. Medvedev, who has carried out a detailed investigation of the case, argued in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) that the Union Bureau of Mensheviks did not exist. "The political trials of the late twenties and early thirties produced a chain reaction of repression, directed primarily against the old technical intelligentsia, against Cadets who had not emigrated when they could have, and against former members of the Social Revolutionary, Menshevik, and nationalist parties."

Isaak Illich Rubin was sentenced to a 5-year term of imprisonment. This testimony of Rubin was used in building a case against Riazanov, Nikolai Sukhanov and other colleagues at the Marx-Engels Institute. Riazanov was dismissed as director of the institute in February 1931, and expelled from the Communist Party. Riazanov was arrested by the OGPU but as he refused to confess he did not appear in court and instead was sent into exile to the the city of Saratov.

In the summer of 1932 Joseph Stalin became aware that opposition to his policies were growing. Some party members were publicly criticizing Stalin and calling for the readmission of Leon Trotsky to the party. When the issue was discussed at the Politburo, Stalin demanded that the critics should be arrested and executed. Sergey Kirov, who up to this time had been a staunch Stalinist, argued against this policy. When the vote was taken, the majority of the Politburo supported Kirov against Stalin.

In the spring of 1934 Kirov put forward a policy of reconciliation. He argued that people should be released from prison who had opposed the government's policy on collective farms and industrialization. Once again, Stalin found himself in a minority in the Politburo. After years of arranging for the removal of his opponents from the party, Stalin realized he still could not rely on the total support of the people whom he had replaced them with. Stalin no doubt began to wonder if Kirov was willing to wait for his mentor to die before becoming leader of the party. Stalin was particularly concerned by Kirov's willingness to argue with him in public. He feared that this would undermine his authority in the party.

As usual, that summer Kirov and Stalin went on holiday together. Stalin, who treated Kirov like a son, used this opportunity to try to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé.

Sergey Kirov was assassinated by a young party member, Leonid Nikolayev, on 1st December, 1934. Victor Kravchenko, pointed out: "Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks."

Walter Duranty, the New York Times correspondent based in Moscow argued that Nikolayev was part of a larger plot: "The details of Kirov's assassination at first pointed to a personal motive, which may indeed have existed, but investigation showed that, as commonly happens in such cases, the assassin Nikolaiev had been made the instrument of forces whose aims were treasonable and political. A widespread plot against the Kremlin was discovered, whose ramifications included not merely former oppositionists but agents of the Nazi Gestapo. As the investigation continued, the Kremlin's conviction deepened that Trotsky and his friends abroad had built up an anti-Stalinist organisation in close collaboration with their associates in Russia, who formed a nucleus or centre around which gradually rallied divers elements of discontent and disloyalty. The actual conspirators were comparatively few in number, but as the plot thickened they did not hesitate to seek the aid of foreign enemies in order to compensate for the lack of popular support at home."

Robin Page Arnot, a member of the British Communist Party, argued that the conspiracy was led by Leon Trotsky. This resulted in the arrest of Genrikh Yagoda, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Nikolay Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov and eleven other party members who had been critical of Stalin. "In December 1934 one of the groups carried through the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, a member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Subsequent investigations revealed that behind the first group of assassins was a second group, an Organisation of Trotskyists headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev. Further investigations brought to light definite counter-revolutionary activities of the Rights (Bukharin-Rykov organisations) and their joint working with the Trotskyists."

However, according to Alexander Orlov, a NKVD officer, "Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov".

The first ever show show trial took place in August, 1936, of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin. Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

Most journalists covering the trial were convinced that the confessions were statements of truth. The Observer reported: "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine." The The New Statesman commented: "Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation."

Anna Louise Strong, of the Moscow Daily News, defended the Great Purge: "The key to the terror, most probably, in actual, extensive penetration of the GPU by a Nazi fifth column, in many actual plots and in the impact of these on a highly suspicious man who saw his own assassination plotted and believed he was saving the Revolution by drastic purge... Stalin engineered the country's modernization ruthlessly, for he was born in a ruthless land and endured ruthlessness from childhood. He engineered suspiciously, for he had been five times exiled and must have been often betrayed. He condoned, and even authorized outrageous acts of the political police against innocent people, but so far no evidence is produced that he consciously framed them."

Walter Duranty was the New York Times journalist based in Moscow. He wrote in the The New Republic that while watching the trial he came to the conclusion "that the confessions are true". Based on these comments the editor of the journal argued: "Some commentators, writing at a long distance from the scene, profess doubt that the executed men (Zinoviev and Kamenev) were guilty. It is suggested that they may have participated in a piece of stage play for the sake of friends or members of their families, held by the Soviet government as hostages and to be set free in exchange for this sacrifice. We see no reason to accept any of these laboured hypotheses, or to take the trial in other than its face value. Foreign correspondents present at the trial pointed out that the stories of these sixteen defendants, covering a series of complicated happenings over nearly five years, corroborated each other to an extent that would be quite impossible if they were not substantially true. The defendants gave no evidence of having been coached, parroting confessions painfully memorized in advance, or of being under any sort of duress."

Leon Trotsky, who was living in exile in Mexico City, was furious with Duranty and described him as a "hypocritical psychologist" who tried to explain away the terrors of the regime with "glib and facile phrases." Trotsky condemned Joseph Stalin "for betraying socialism and dishonoring the revolution" and describing the leadership as being "dominated by a clique which holds the people in subjection by oppression and terror." The trial, Trotsky claimed was a "frame-up" that lacked "objectivity and impartiality" and volunteered to go before an international commission to prove his innocence."

In September, 1936, Stalin appointed Nikolai Yezhov as head of the NKVD, the Communist Secret Police. Yezhov quickly arranged the arrest of all the leading political figures in the Soviet Union who were critical of Stalin. The Secret Police broke prisoners down by intense interrogation. This included the threat to arrest and execute members of the prisoner's family if they did not confess. The interrogation went on for several days and nights and eventually they became so exhausted and disoriented that they signed confessions agreeing that they had been attempting to overthrow the government.

In January, 1937, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, and fifteen other leading members of the Communist Party were put on trial. They were accused of working with Leon Trotsky in an attempt to overthrow the Soviet government with the objective of restoring capitalism. Robin Page Arnot, a leading figure in the British Communist Party, wrote: "A second Moscow trial, held in January 1937, revealed the wider ramifications of the conspiracy. This was the trial of the Parallel Centre, headed by Piatakov, Radek, Sokolnikov, Serebriakov. The volume of evidence brought forward at this trial was sufficient to convince the most sceptical that these men, in conjunction with Trotsky and with the Fascist Powers, had carried through a series of abominable crimes involving loss of life and wreckage on a very considerable scale."

Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "After they saw that Piatakov was ready to collaborate in any way required, they gave him a more complicated role. In the 1937 trials he joined the defendants, those whom he had meant to blacken. He was arrested, but was at first recalcitrant. Ordzhonikidze in person urged him to accept the role assigned to him in exchange for his life. No one was so well qualified as Piatakov to destroy Trotsky, his former god and now the Party's worst enemy, in the eyes of the country and the whole world. He finally agreed I to do it as a matter of 'the highest expediency,' and began rehearsals with the interrogators."

One of the journalists covering the trial, Lion Feuchtwanger, commented: "Those who faced the court could not possibly be thought of as tormented and desperate beings. In appearance the accused were well-groomed and well-dressed men with relaxed and unconstrained manners. They drank tea, and there were newspapers sticking out of their pockets... Altogether, it looked more like a debate... conducted in conversational tones by educated people. The impression created was that the accused, the prosecutor, and the judges were all inspired by the same single - I almost said sporting - objective, to explain all that had happened with the maximum precision. If a theatrical producer had been called on to stage such a trial he would probably have needed several rehearsals to achieve that sort of teamwork among the accused."

Yuri Piatakov and twelve of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to death. Karl Radek and Grigori Sokolnikov were sentenced to ten years. Feuchtwanger commented that Radek "gave the condemned men a guilty smile, as though embarrassed by his luck." Maria Svanidze, who was later herself to be purged by Joseph Stalin wrote in her diary: "They arrested Radek and others whom I knew, people I used to talk to, and always trusted.... But what transpired surpassed all my expectations of human baseness. It was all there, terrorism, intervention, the Gestapo, theft, sabotage, subversion.... All out of careerism, greed, and the love of pleasure, the desire to have mistresses, to travel abroad, together with some sort of nebulous prospect of seizing power by a palace revolution. Where was their elementary feeling of patriotism, of love for their motherland? These moral freaks deserved their fate.... My soul is ablaze with anger and hatred. Their execution will not satisfy me. I should like to torture them, break them on the wheel, burn them alive for all the vile things they have done."

On 14th July 1937, Walter Duranty wrote another article on the show-trials, The Riddle of Russia, for The New Republic. He argued that since November 1934, that agents working for Nazi Germany had infiltrated the ranks of the Soviet leadership, while Trotsky, like an exiled monarch, was the leader of the conspiracy to overthrow Stalin. Duranty went on to claim that this conspiracy had involved many men in the highest echelons of government. But now "their Trojan horse was broken, and its occupants destroyed."

James William Crowl, the author of Angels in Stalin's Paradise (1982 has argued: "Although Louis Fischer reserved judgment on the trials, Duranty vigorously defended them. According to him, Trotsky had created a spy network at the very time that Germany and Japan were spreading their own spy organizations in Russia. He explained that the two groups shared a hatred for Stalin, and fascist agents had cooperated with the Trotskyites in Kirov's assassination. The show-trials, Duranty insisted, had revealed the Trotskyite-fascist link beyond question. The trials showed just as clearly, he argued (on 14th July, 1937), that Stalin's arrest of thousands of these agents had spared the country from a wave of assassinations. Duranty charged that those who worried about the rights of the defendants or claimed that their confessions had been gained by drugs or torture, only served the interests of Germany and Japan."

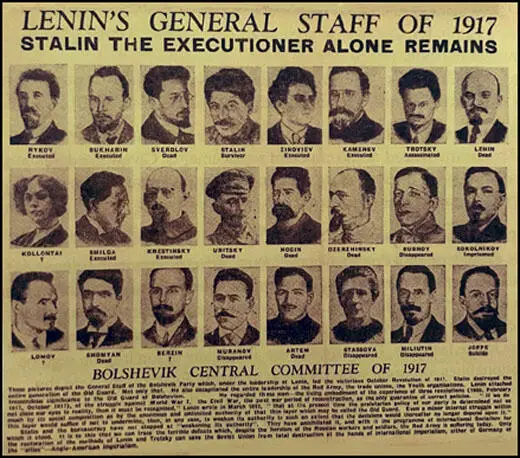

The next show trials took place in March, 1938, and involved twenty-one leading members of the party. This included Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Krestinsky and Christian Rakovsky. They were accused of being involved with Leon Trotsky in a plot against Joseph Stalin and with spying for foreign powers. They were all found guilty and were either executed or died in labour camps.

Stalin now decided to purge the Red Army. Some historians believe that Stalin was telling the truth when he claimed that he had evidence that the army was planning a military coup at this time. Leopold Trepper, head of the Soviet spy ring in Germany, believed that the evidence was planted by a double agent who worked for both Stalin and Hitler. Trepper's theory is that the "chiefs of Nazi counter-espionage" led by Reinhard Heydrich, took "advantage of the paranoia raging in the Soviet Union," by supplying information that led to Stalin executing his top military leaders.

In June, 1937, Mikhail Tukhachevsky and seven other top Red Army commanders were charged with conspiracy with Germany. All eight were convicted and executed. All told, 30,000 members of the armed forces were executed. This included fifty per cent of all army officers.

The last stage of the terror was the purging of the NKVD. Stalin wanted to make sure that those who knew too much about the purges would also be killed. Stalin announced to the country that "fascist elements" had taken over the security forces which had resulted in innocent people being executed. He appointed Lavrenti Beria as the new head of the Secret Police and he was instructed to find out who was responsible. After his investigations, Beria arranged the executions of all the senior figures in the organization.

Walter Duranty always underestimated the number killed during the Great Purge. As Sally J. Taylor, the author of Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990) has pointed out: "As for the number of resulting casualties from the Great Purge, Duranty's estimates, which encompassed the years from 1936 to 1939, fell considerably short of other sources, a fact he himself admitted. Whereas the number of Party members arrested is usually put at just above one million, Duranty's own estimate was half this figure, and he neglected to mention that of those exiled into the forced labor camps of the GULAG, only a small percentage ever regained their freedom, as few as 50,000 by some estimates. As to those actually executed, reliable sources range from some 600,000 to one million, while Duranty maintained that only about 30,000 to 40,000 had been killed."

Primary Sources

(1) J. T. Murphy, The Errors of Trotskyism (1925)

It is said Comrade Trotsky wanted democracy to come from below, and the Central Committee wanted to introduce it from above. For Comrade Trotsky or anyone else to speak of introducing the Resolutions of the Party Conference from “below,” that is to begin with the locals spreading upwards, is to again forget the first principles of Bolshevik Party organisation, and thereby strengthen the political position of the opponents of the Party. Of what use is it to elect an Executive Committee if the decisions of the Party Congress can be effectively carried through without the election of such a committee? And this is what the proposals amounts to. It finds its echo amongst many industrialists in this country and also amongst reformist Labour leaders. The industrialists plead for more ballots, more referendums, impervious to the fact that they are simply transferring the Parliamentarism of the Labour Party to the industrial arena. The union leaders respond, and the “coming from below” turns out to be more often than not the means for preventing action than securing it.

(2) Alexander Orlov was a NKVD officer who escaped to the United States.

Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov, "the beloved son of the party", a member of the Politburo, he then would be justified in demanding blood for blood.

(3) Leon Trotsky, Stalin (1941)

Much was said in the Moscow trial about my alleged "hatred" for Stalin. Much was said in the Moscow trial about it, as one of the motives of my politics. Toward the greedy caste of upstarts which oppresses the people "in the name of socialism" I have nothing but irreducible hostility, hatred if you like. But in this feeling there is nothing personal. I have followed too closely all the stages of the degeneration of the revolution and the almost automatic usurpation of its conquests; I have sought too stubbornly and meticulously the explanation for these phenomena in objective conditions for me to concentrate my thoughts and feelings on one specific person. My standing does not allow me to identity the real stature of the man with the giant shadow it casts on the screen of the bureaucracy. I believe I am right in saying I have never rated Stalin so highly as to be able to hate him.

(4) Gregory Zinoviev, speech at his trial (August, 1936)

I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky.

(5) The Observer (23rd August, 1936)

It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine.

(6) The New Republic (2nd September, 1936)

Some commentators, writing at a long distance from the scene, profess doubt that the executed men (Zinoviev and Kamenev) were guilty. It is suggested that they may have participated in a piece of stage play for the sake of friends or members of their families, held by the Soviet government as hostages and to be set free in exchange for this sacrifice. We see no reason to accept any of these laboured hypotheses, or to take the trial in other than its face value. Foreign correspondents present at the trial pointed out that the stories of these sixteen defendants, covering a series of complicated happenings over nearly five years, corroborated each other to an extent that would be quite impossible if they were not substantially true. The defendants gave no evidence of having been coached, parroting confessions painfully memorized in advance, or of being under any sort of duress.

(7) The New Statesman (5th September, 1936)

Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation.

(8) Leon Trotsky, The Trial of the Seventeen (22nd January, 1937).

How could these old Bolsheviks who went through the jails and exiles of Czarism, who were the heroes of the civil war, the leaders of industry, the builders of the party, diplomats, turn out at the moment of "the complete victory of socialism" to be saboteurs, allies of fascism, organizer of espionage, agents of capitalist restoration? Who can believe such accusations? How can anyone be made to believe them. And why is Stalin compelled to tie up the fate of his personal rule with these monstrous, impossible, nightmarish juridical trials?

First and foremost, I must reaffirm the conclusion I had previously drawn that the ruling tops feel themselves more and more shaky. The degree of repression is always in proportion to the magnitude of the danger. The omnipotence of the soviet bureaucracy, its privileges, its lavish mode of life, are not cloaked by any tradition, any ideology, any legal norms.

The ruling caste is unable, however, to punish the opposition for its real thoughts and actions. The unremitting repressions are precisely for the purpose of preventing the masses from the real program of Trotskyism, which demands first of all more equality and more freedom for the masses.

(9) Max Shachtman, Socialist Appeal (October 1936)

Unless we are the "gullible idiots" who Trotsky says would have to people the world if the charges made against the sixteen men just tried and shot in Moscow, were to be believed, we must conclude that the very indictment and execution of Zinoviev, Kamenev and the fourteen others constitute in actuality the most crushing indictment yet made of the Stalin regime itself. The real accused in the trial were not on the defendants' bench before the Military Tribunal. They were and they remain the usurping masters of the Kremlin - concocters of a hideous frame-up.

The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?

Leon Trotsky, organizer and leader, together with Lenin, of the October Revolution, and founder of the Comintern.

Zinoviev: 35 years of his life in the Bolshevik party; Lenin's closest collaborator in exile and nominated by him as first chairman of the Communist International; chairman of the Petrograd Soviet for years; member of the Central Committee and the Political Bureau of the C.P. for years.

Kamenev: also 35 years spent in the Bolshevik party; chairman of the Political Bureau in Lenin's absence; chairman of the Moscow Soviet; chairman of the Council of Labor and Defense; Lenin's literary executor.

Smirnov: head of the famous Fifth Army during the civil war; called the "Lenin of Siberia;" a member of the Bolshevik party for decades.

Yevdokimov: official party orator at Lenin's funeral; leader of the Leningrad party organization for many years; member of the Central Committee at the time Kirov died.

Ter-Vaganian: theoretical leader of the Armenian communists; founder and first editor of the party's review, "Under the Banner of Marxism."

Mrachkovsky: defender of Ekaterinoslav from the interventionist Czechs and the White troop during the civil war.

Bakayev: old Bolshevik leader in Moscow; member of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission during Lenin's time.

Sokolnikov: Soviet ambassador to England; creator of the "chervonetz," the first stable Soviet currency.

Tomsky: head of the Russian trade union center for years; old worker-Bolshevik; member of the Central Committee and Political Bureau for years.

Rykov: old Bolshevik leader; Lenin's successor as chairman of the Council of People's Commissars.

Serebriakov: Stalin's predecessor in the post of secretary of the C.P.

Bukharin: for years one of the most prominent theoreticians of the Bolsheviks; chairman of the Comintern after Zinoviev; editor of official government organ, Isvestia.

Kotsubinsky: one of the main founders of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic.

General Schmidt; head of one of the first Red Cavalry brigades in the Ukraine and one of the country's liberators from the White forces.

Other heroes of the Civil War, like General Putna, military attache till yesterday of the Soviet Embassy in London; Gertik and Gaevsky; Shaposhnikov, director of the Academy of the General Staff; Klian Kliavin.

Heads of banking institutions; chiefs of industrial trusts; heads of educational and scientific institutions; party secretaries from one end of the land to the other; authors (Selivanovsky, Serebriakova, Katayev, Friedland, Tarassov-Rodiondv); editors of party papers; high government officials (Prof. Joseph Lieberberg, chairman of the Executive Committee of the Jewish Autonomous Republic of Biro-Bijan); etc., etc.

Now to charge, as has been done, all these men and women, plus hundreds and perhaps thousands of others, with having engaged to one extent or another, in an assassination plot, is equivalent, at the very outset and on the face of the matter, to an involuntary admission by the accusing bureaucracy.

1. That its much-vaunted popularity and the universality of its support among the population, is fantastically exaggerated.

2. That it has created such a regime in the party and the country as a whole, that the very creators of the Bolshevik party and revolution, its most notable and valiant defenders in the crucial and decisive early years, could find no normal way of expressing their dissatisfaction or opposition to the ruling bureaucracy and found that the only way of fighting the latter was the way chosen, for example, by the Nihilists in their struggle against Czarist despotism, namely, conspiracy and individual terrorism.

3. That the "classless socialist society irrevocably" established by Stalin is so inferior to Fascist barbarism on the political, economic and cultural fields, that hundreds of men whose whole lives were prominently devoted to the cause of the proletariat and its emancipation, decided to discard everything achieved by 19 years of the Russian Revolution in favor of a Nazi regime.

4. And, not least of all, that the Russian Revolution was organized and led by an unscrupulous and perfidious hand of swindlers, liars, scoundrels, mad dogs and assassins. Or, more correctly, if these were not their characteristic in 1917 and the years immediately thereafter, then there was something about the gifted and beloved leadership of Stalinism that reduced erstwhile revolutionists and men of probity and integrity to the level of swindlers, liars, scoundrels, mad dogs and assassins.

These are the outstanding counts in the self-indictment of the bureaucracy. To them must be added the charge of a clumsy and cynical frame-up. Even a casual examination of the very carefully edited record of the trial that has thus far been made public, so thoroughly reveals its trumped-up, staged nature, as to deprive all the avidly made "confessions" of so much as an ounce of validity.

(10) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935)

At the December Congress Zinoviev and Kamenev played possum, but in the following spring they joined Trotsky to form a united opposition bloc which concentrated its assault upon Stalin's agrarian policy, demanding that the kulaks be expropriated immediately. Stalin refused to yield; he met blows with double blows and used all the weapons in his armoury, from control of the Party machine and the Press to police regulations about public meetings. It availed his opponents little to say that he forced them into a position of illegality, into holding secret conclaves or using "underground" printing-presses to disseminate their views. The news of a secret meeting which they held in the woods near Moscow in the autumn of 1926 produced such a furore that Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev were expelled from the Politburo without a voice being raised to defend them. The six chief opposition leaders yielded to public indignation and issued a formal disavowal of "underground tactics" and "illegal factional meetings", but in the following spring and summer they returned to the charge in the belief, which perhaps was justified, that the Party masses were really stirred by the kulak danger. Again Stalin muffled the attack by control of the Press and public meetings. The opposition leaders lost their heads; on November 7th, anniversary of the Revolution, they "came out into the streets" in Moscow and Leningrad and appealed to the people from balconies or in the public squares. The attempt was a fiasco; the public was indifferent; there was no excitement, much less rioting or violence. But in Soviet law this was counter-revolution. For the last time Trotsky had played by his own act into Stalin's hand; this error was fatal - political suicide. On December 18th the Fifteenth Party Congress expelled the seventy-five leading members of the opposition from the Communist Party; its adherents followed, neck and crop. In January, 1928, the oppositionists great and small were scattered in exile across Siberia and Central Asia.

(11) Nadezhda Khazina, Hope Against Hope (1971)

In the period of the Yezhov terror - the mass arrests came in waves of varying intensity - there must sometimes have been no more room in the jails, and to those of us still free it looked as though the highest wave had passed and the terror was abating. After each show trial, people sighed, "Well, it's all over at last." What they meant was: "Thank God, it looks as though I've escaped. But then there would be a new wave, and the same people would rush to heap abuse on the "enemies of the people."

Wild inventions and monstrous accusations had become an end in themselves, and officials of the secret police applied all their ingenuity to them, as though reveling in the total arbitrariness of their power.

The principles and aims of mass terror have nothing in common with ordinary police work or with security. The only purpose of terror is intimidation. To plunge the whole country into a state of chronic fear, the number of victims must be raised to astronomical levels, and on every floor of every building there must always be several apartments from which the tenants have suddenly been taken away. The remaining inhabitants will be model citizens for the rest of their lives - this was true for every street and every city through which the broom has swept. The only essential thing for those who rule by terror is not to overlook the new generations growing up without faith in their elders, and keep on repeating the process in systematic fashion.

Stalin ruled for a long time and saw to it that the waves of terror recurred from time to time, always on even greater scale than before. But the champions of terror invariably leave one thing out of account - namely, that they can't kill everyone, and among their cowed, half-demented subjects there are always witnesses who survive to tell the tale.

(12) In November, 1933, Osip Mandelstam wrote a poem about Stalin (the Kremlin mountainer). Ossette was a reference to the rumour that Stalin was from a people of Iranian stock that lived in an area north of Georgia. The poem resulted in Mandelstam being sent to a NKVD labour camp where he died.

We live, deaf to the land beneath us,

Ten steps away no one hears our speeches,

All we hear is the Kremlin mountaineer,

The murderer and peasant-slayer.

His fingers are fat as grubs

And the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips,

His cockroach whiskers leer

And his boot tops gleam.

Around him a rabble of thin-necked leaders -

fawning half-men for him to play with.

The whinny, purr or whine

As he prates and points a finger,

One by one forging his laws, to be flung

Like horseshoes at the head, to the eye or the groin.

And every killing is a treat

For the broad-chested Ossete.

(13) Robin Page Arnot, The Labour Monthly (November 1937)

In December 1934 one of the groups carried through the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, a member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Subsequent investigations revealed that behind the first group of assassins was a second group, an Organisation of Trotskyists headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev. Further investigations brought to light definite counter-revolutionary activities of the Rights (Bucharin-Rykov organisations) and their joint working with the Trotskyists. The group of fourteen constituting the Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Centre were brought to trial in Moscow in August 1936, found guilty, and executed. In Siberia a trial, held in November, revealed that the Kemerovo mine had been deliberately wrecked and a number of miners killed by a subordinate group of wreckers and terrorists. A second Moscow trial, held in January 1937, revealed the wider ramifications of the conspiracy. This was the trial of the Parallel Centre, headed by Pyatakov, Radek, Sokolnikov, Serebriakov. The volume of evidence brought forward at this trial was sufficient to convince the most sceptical that these men, in conjunction with Trotsky and with the Fascist Powers, had carried through a series of abominable crimes involving loss of life and wreckage on a very considerable scale. With the exceptions of Radek, Sokolnikov, and two others, to whom lighter sentences were given, these spies and traitors suffered the death penalty. The same fate was meted out to Tukhachevsky, and seven other general officers who were tried in June on a charge of treason. In the case of Trotsky the trials showed that opposition to the line of Lenin for fifteen years outside the Bolshevik Party, plus opposition to the line of Lenin inside the Bolshevik Party for ten years, had in the last decade reached its finality in the camp of counter-revolution, as ally and tool of Fascism.

(14) Leon Trotsky, Hitler's Austria Coup (12th March, 1938).

There is a tragic symbolism in the fact that the Moscow trial is ending under the fanfare announcing the entry of Hitler into Austria. The coincidence is not accidental. Berlin is of course perfectly informed about the demoralization which the Kremlin clique in its struggle for self-preservation carried into army and the population of the country. Stalin did not move a finger last year when Japan seized two Russian islands on the Amur river: he was then busy executing the best Red generals. With all the more assurance during the new trial could Hitler send his troops into Austria.

No matter what one's attitude toward the defendants at the Moscow trials, no matter how one judges their conduct in the clutches of the G.P.U., All of them - Zinoviev, Kamenev, Smirnov, Piatakov, Radek, Rykov, Bukharin, and many others. - have by the whole course of their lives proved their disinterested devotion to the Russian people and their struggle for liberation.

(15) John Ross Campbell, Daily Worker (5th March, 1938)

Every weak, corrupt or ambitious enemy of socialism within the Soviet Union has been hired to do dirty, evil work. In the forefront of all the wrecking, sabotage and assassination is Fascist agent Trotsky. But the defences of the Soviet Union are strong. The nest of wreckers and spies has been exposed before the world and brought before the judgement of the Soviet Court. We know that Soviet justice will be fearlessly administered to those who have been guilty of unspeakable crimes against Soviet people. We express full confidence in our Brother Party.

(16) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin (1949)

In Tsarist days political offenders had enjoyed certain privileges and been allowed to engage in self-education and even in political propaganda. Oppositional memoranda, pamphlets, and periodicals had circulated half freely between prisons and had occasionally been smuggled abroad. Himself an ex-prisoner, Stalin knew well that jails and places of exile were the 'universities' of of the revolutionaries. Recent events taught him to take no risks. From now on all political discussion and activity in the prisons and places of exile was to be mercilessly suppressed; and the men of the opposition were by privation and hard labour to be reduced to such a miserable, animal-like existence that they should be incapable of the normal processes of thinking and of formulating their views.

(17) Nikita Khrushchev claimed that it was some time after Stalin's death before he realized the extent of his crimes.

I still mourned Stalin as an extraordinary powerful leader. I knew that his power had been exerted arbitrarily and not always in the proper direction, but in the main Stalin's strength, I believed, had still been applied to the reinforcement of Socialism and to the consolidation of the gains of the October Revolution. Stalin may have used methods which were, from my standpoint, improper or even barbaric, but I hadn't yet begun to challenge the very basis of Stalin's claim to a special honour in history. However, questions were beginning to arise for which I had no ready answer. Like others, I was beginning to doubt whether all the arrests and convictions had been justified from the standpoint of judicial norms. But then Stalin had been Stalin. Even in death he commanded almost unassailable authority, and it still hadn't occurred to me that he had been capable of abusing his power.

(18) Freda Kirchwey, The Nation (March, 1938)

The trial of Bukharin and his fellow oppositionists has broken about the ears of the world like the detonation of a bomb. One can hear the cracking of liberal hopes; of the dream of anti-fascist unity; of a whole system of revolutionary philosophy wherever democracy is threatened, the significance of the trial will be anxiously weighed.

In spite of the trials, I believe Russia is dependable; that it wants peace, and will join in any joint effort to check Hitler and Mussolini, and will also fight if necessary. Russia is still the strongest reason for hope.

(19) Robin Page Arnot, Fascist Agents Exposed in the Moscow Trials (1938)

Systematic efforts have been made by the reactionary capitalist press and elements within the Labour movement to create the opinion that the accused are convicted mainly upon testimony of their own confessions and a subtle attempt is made to create prejudice by printing the word “confession” within quotation marks.

Nothing could be further from the truth. First of all it should be noted that the detailed avowals of guilt are not confessions at all in the ordinary sense of the word, in the sense of “making a clean breast of it.” The prisoners talk about things which are already proved and which they cannot deny. Their statements concern mainly the question of the degree of guilt or their own share, large or small, in specific criminal activities. An interesting illustration of this was provided by the accused Krestinsky in connection with the letter which he claimed to have sent to Trotsky in 1927, severing his connection with the Trotskyist movement. During the first day of the trial, he insisted that the contents of this letter cleared him of all suspicions and demanded to know why it had not been produced. Two days later to his obvious discomfiture the very letter was produced in court by State Prosecutor Vyshinsky. After Rakovsky, who had read the letter in 1927, had identified it, and Krestinsky had agreed that the identification was correct, Vyshinsky read the contents only to disclose the fact that they were entirely different in meaning to that which Krestinsky had endeavoured to give them two days before.

Similarly the police spy Zubarev, confronted with the Tsarist police inspector under whose direction he had worked in Kotelnich during 1908-09 looked for all the world as though he had suddenly seen a ghost from his own past. The confrontation of Bukharin with the “Left” Social-Revolutionaries Karelin and Kamkov with whom he had been in conspiratorial alliance in 1918 to overthrow the Soviet Government, arrest and kill Lenin, Stalin and Sverdlov and form a new government of Bukharinites and “Left” Social-Revolutionaries was as conclusive as it was dramatic, and was backed up by the production of three of the people who had been members of Bukharin’s own group of “Left” Communists at that time and who had participated in the plot.

Expert testimony from authoritative medical men in the Soviet Union in connection with the murder of Gorky, Kuibyshev, Menshinsky and Pashkov-Gorky, documentary evidence and the evidence of facts: train wrecks, slaughter of large numbers of livestock, attempts at bandit insurrections, etc., combined to build a cast-iron case for the prosecution out of which, despite all their wriggling, attempts at evasion and efforts to shift responsibility from their own shoulders to others, not one of the accused could escape. But in the case of no individual or crime did Vyshinsky depend solely upon the testimony of the accused.

In this connection it is interesting to note that if the propaganda of the pro-fascist section of the capitalist press, and the confused Liberal and Socialist journals were based upon fact, the whole assortment of counter-revolutionary traitors united in these blocs would have been arrested and disposed of 20 months before, immediately following the much-vaunted “confessions” (as hostile newspapers print it) of the prisoners convicted during the trial of the Trotskyist-Zinoviev group. It is obvious that the prisoners convicted in the Zinoviev, trial, held back what they certainly knew, and only admitted their guilt in those crimes of which the proof was already so overwhelming that denial was futile. By discussing these proofs of crimes with the prosecutor in court, by questioning witnesses, cross-examinations, and energetic defence, each of the prisoners tried to the best of his ability or the ability of the lawyers defending him, to evade some measure of responsibility and to lighten the punishment to be meted out to him. The actions of the prisoners themselves during the trial, their final speeches and their last minute appeals for clemency, all showed very clearly that from beginning to end their fight was carried on to evade full punishment for crimes of which the State Prosecutor already had such overwhelming proof as to secure conviction from any court.

(20) William Stephenson, head of the British Secret Intelligence Service in the United States, report on Reinhard Heydrich (1937)

The most sophisticated apparatus for conveying top-secret orders was at the service of Nazi propaganda and terror. Heydrich had made a study of the Russian OGPU, the Soviet secret security service. He then engineered the Red Army purges carried out by Stalin. The Russian dictator believed his own armed forces were infiltrated by German agents as a consequence of a secret treaty by which the two countries helped each other rearm. Secrecy bred suspicion, which bred more secrecy, until the Soviet Union was so paranoid it became vulnerable to every hint of conspiracy.

Late in 1936, Heydrich had thirty-two documents forged to play on Stalin's sick suspicions and make him decapitate his own armed forces. The Nazi forgeries were incredibly successful. More than half the Russian officer corps, some 35,000 experienced men, were executed or banished.

The Soviet chief of Staff, Marshal Tukhachevsky, was depicted as having been in regular correspondence with German military commanders. All the letters were Nazi forgeries. But Stalin took them as proof that even Tukhachevsky was spying for Germany. It was a most devastating and clever end to the Russo-German military agreement, and it left the Soviet Union in absolutely no condition to fight a major war with Hitler.

(21) Nikita Khrushchev, speech, 20th Party Congress (February, 1956)

Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient co-operation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position, was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation. This was especially true during the period following the 17th Party Congress, when many prominent Party leaders and rank-and-file Party workers, honest and dedicated to the cause of communism, fell victim to Stalin's despotism.

Stalin originated the concept "enemy of the people". This term automatically rendered it unnecessary that the ideological errors of a man or men engaged in a controversy be proven; this term made possible the usage of the most cruel repression, violating all norms of revolutionary legality, against anyone who in any way disagreed with Stalin, against those who were only suspected of hostile intent, against those who had bad reputations.

(22) J. T. Murphy, Forty Years Hard — For What? (1958)

The premise of the "World Proletarian Revolution" was accepted as a political fact and remains so in Communist thinking to this day. Actually, it became the substance of our faith. It appeared to us to be so, and therefore it was so, and all the stirring social upheavals fitted into the pattern of our thinking. When the revolutionary wave subsided to the frontiers of Soviet Russia, did that raise any doubts? Not at all. There will be wave on wave, we said. Meanwhile, we are in a ‘period of partial stabilisation of capitalism’. ‘We’ve got a breathing space,’ said Lenin, in which to consolidate our gains and prepare for the next advance - which simply did not come. Instead, Fascism raised its head. With that fading out of the apparent ‘fact’ of the World Proletarian Revolution, it didn’t fade out of our faith. The General Staff of the Parties ‘On the Road to Insurrection’ still believed they were travelling that road, but ceased to call on the workers of all lands to take arms in hand and overthrow their toppling governments and changed its line in keeping with the ebb tide of World Revolution. The Soviets switched on to the line of ‘Socialism in One Country’, ‘Hands Off Russia’, ‘Defend the Soviet Union’, ‘Collective Security’, ‘United Front from Below’, ‘People’s Front’ and so on - all orchestrated by the General Staff of the Parties of Insurrection. But the Bolshevisation of the C.P.G.B. went on apace to remodel the party on the principles of democratic centralism, which are principles of a military, insurrectionary party with militaristic and insurrectionary aims. Centralisation of authority is common to all military organisation and is to be tolerated if there is a war on. But if there isn’t a war on, doesn’t that centralisation become transformed into pompous bureaucracy and Blimpian stupidity? Isn’t the strange history of the C.P.G.B. in its first twenty years, to be explained by the artificiality of its existence, and its illusions rather than its mendacity? The premises for the existence of a party of insurrection did not exist. Lenin’s ‘World Proletarian Revolution’ existed only as the article of faith of the C.I. and its sections. Does not the artificiality of the party’s existence also explain the fantastic record of its relations with the Labour and Socialist movement? At one moment the C.P. wants to "take the leaders by the hand as a preliminary to seizing them by the throat". At the next it wanted affiliation and then it didn’t. We built a Left Movement of fellow travellers in the Labour Party and then we destroyed it. We built a Minority Movement in the trade unions and then liquidated it. Then the Labour Party "is in ruins" and the day of the Mass Communist Party has arrived! That was just after a general election in which the Labour Party polled seven million votes and the Communist Party had polled seventy thousand votes and lost its deposits in almost every constituency it contested. Some ruins! Some mass party! Some clarity! The leadership (still thinking the World Proletarian Revolution was on), was scared of the idea of ‘aiding capitalism to recover’ - the crime of which I myself was accused when proposing that Soviet Russia should be granted credits for the purpose of buying machinery from British engineering factories where masses of engineering workers were unemployed. Instead, therefore, of the Communist Party becoming a party leading a class it became a party of ideologues, interpreting the course of history according to doctrine, and concerned more with loyalty to doctrine than to the living realities of social transformation. It is not subservience to Stalin (though that was bad enough), which accounts for the fantastic gyrations of the C.P.G.B., but the fact that it was beating the air with a false interpretation of the social process and turning itself into a little party of romantic ideologues.

There is no evidence either in this outline of the Communist Party’s history, nor in any of their publications, that the C.P. realised, when it flung itself on the side of Churchill and the Coalition in the course of the war, that by doing so it had changed the premises of its existence from the ‘class war’ to that of social co-operation of all classes. There is not the slightest indication that any of them realised that the theoretical premises of Marxism and Leninism were being flouted by life. With the same religious fervour which had marked it from its inception it plunged into the war of survival, ready and willing to fight in fields, factories and workshops and swim furiously with the tide of life; but cherishing still the hope that after survival they could carry their harvest of recruits into the holy church of the ‘World Proletarian Revolution’. Stalin had this idea too. He proclaimed at the beginning of the war that it was a National Patriotic War, not only for survival but also for the liberation of the nations from the grip of Hitlerism. Once survival had been secured, he proceeded from defence to attack and transformed the final stages of the war into a war of imperial conquest in the name of extending the socialist revolution, in Poland, Germany, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Romania.

(23) Sally J. Taylor, Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990)

As for the number of resulting casualties from the Great Purge, Duranty's estimates, which encompassed the years from 1936 to 1939, fell considerably short of other sources, a fact he himself admitted. Whereas the number of Party members arrested is usually put at just above one million, Duranty's own estimate was half this figure, and he neglected to mention that of those exiled into the forced labor camps of the GULAG, only a small percentage ever regained their freedom, as few as 50,000 by some estimates. As to those actually executed, reliable sources range from some 600,000 to one million, while Duranty maintained that only about 30,000 to 40,000 had been killed.