J. T. (Jack) Murphy

John Thomas (Jack) Murphy was born in Manchester in 1888. He left school at thirteen and became an apprentice at the Vickers engineering factory. A religious young man, he became a superintendent of a local Sunday School and a preacher in the Primitive Methodist Church.

Murphy initially argued with his workmates about the importance of religion. However, he was eventually converted to socialism and he abandoned his religious faith. He came under the influence of Tom Mann and James Connally and became an advocate of revolutionary socialism.

Murphy joined the Socialist Labour Party (SLP). Other members included John S. Clarke, Willie Paul, Arthur McManus, Neil MacLean, James Connally, John MacLean and Tom Bell.

Murphy, like other members of the SLP became involved in the campaign against Britain's involvement in the First World War and took part in the fight against conscription. During the war Murphy moved to Sheffield where he became involved in the local Workers' Committee. In one article that he wrote Murphy raised the issue why trade union officials sometimes betrayed their members: "One of the most noticeable features in recent trade union history is the conflict between the rank and file of the trade unions and their officials, and it is a feature which, if not remedied, will lead us all into muddle and ultimately disaster.... A perusal of the history of the labour movement, both industrial and political, will reveal to the critical eye certain tendencies and certain features which, when acted upon by external conditions, will produce the type of persons familiar to us as trade union officials and labour leaders. Everyone is aware that usually a man gets into office on the strength of revolutionary speeches, which strangely contrast with those of a later date after a period in office."

Murphy had been impressed with the achievements of the Bolsheviks following the Russian Revolution and in April 1920 he joined forces with Tom Bell, Willie Gallacher, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Rajani Palme Dutt, Robin Page Arnot, Albert Inkpin and Willie Paul to establish the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers.

Murphy travelled to Moscow and played a significant role in establishing the Red International of Labor Unions (RILU), an attempt to unite revolutionary trade unionists worldwide into a single organization. Murphy, Andres Nin, Alfred Rosmer and Mikhail Tomsky were elected as the first leaders of the RILU.

Murphy became a supporter of Joseph Stalin in his struggle with Leon Trotsky. At a council meeting of the CPGB in 1924, Murphy moved the main resolution denouncing Trotsky for his “open attack upon the present leadership of the Communist International, which in the opinion of the CPGB, will not only definitely encourage the British Imperialists, the bitterest enemies of Soviet Russia, but will also encourage their lackeys of the Second International, and those other elements who stand for the liquidation of the Communist International and the Communist Party in this country.”

On 4th August 1925, Murphy and 11 other activists, Robin Page Arnot, Wal Hannington, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Harry Pollitt, Albert Inkpin, Arthur McManus, Tom Bell, William Rust, William Gallacher and John Campbell were arrested for being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain and charged with various offences.

Tom Bell explained: "The indictment against the twelve read as follows: That between 1 January, 1924, and 21 October, 1925, the prisoners had: 1. Conspired to publish a seditious libel. 2. Conspired to incite to commit breaches of the Incitement to Mutiny Act, 1797. 3. Conspired to endeavour to seduce persons serving in His Majesty's forces to whom might come certain published books and pamphlets, to wit, the Workers' Weekly, and certain other publications mentioned in the indictment, and to incite them to mutiny." It was believed that the arrests was an attempt by the government to weaken the labour movement in preparation for the impending General Strike.

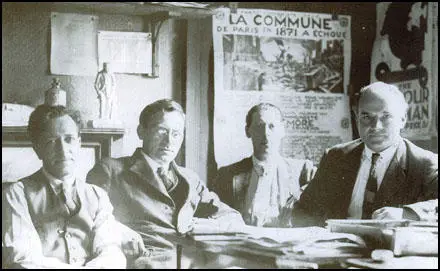

Harry Pollitt, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Albert Inkpin; (Front Row)

John R. Campbell, Arthur McManus, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, Tom Bell.

The Communist Party of Great Britain decided that William Gallacher, John R. Campbell and Harry Pollitt should defend themselves. Tom Bell added: "their speeches were prepared, and approved by the Political Bureau (of the CPGB). To challenge the legality of the proceedings Sir Henry Slesser was engaged to defend the others. During the trial Judge Swift declared that it was "no crime to be a Communist or hold communist opinions, but it was a crime to belong to this Communist Party."

John Campbell later wrote: "The Government was wise enough not to rest its case on the activity of the accused in organising resistance to wage cuts, but on their dissemination of “seditious” communist literature, (particularly the resolutions of the Communist International), their speeches, and occasional articles... Five of the prisoners who had previous convictions, Gallacher, Hannington, Inkpin, Pollitt and Rust, were sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment and the others (after rejecting the Judge’s offer that they could go free if they renounced their political activity) were sentenced to six months."

Murphy published The Political Meaning of the Great Strike in 1926. He argued: "The obvious conclusions to be drawn from this situations and this experience are clear for everyone to see... The General Strike raised the question of class power and the leaders ran away from it, instead of answering with measures commensurate with the developing situation."

In 1926 Murphy travelled to Moscow and was elected to the Presidium and Political Secretariat. He was also an influential member of the Comintern. He was also a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) and headed the British section, which included Ireland and the colonies.

In 1932 Murphy argued that the Communist Party of Great Britain should mount a campaign to pressure employers and the British government to give credits for industrial products to the Soviet Union. Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of the CPGB, disagreed on the grounds that this would solve the country’s market crisis and improve the chances of the British economy surviving the Great Depression. He demanded that Murphy publicly admit his mistake. Murphy refused, and resigned from the CPGB. He wrote to the Political Bureau of the CPGB: "I am sorry to part company with the party after all these years of service to it, but I decline to go about subordinating myself to a policy I do not conscientiously accept, to be silent on questions which I conscientiously deem important, and subject myself to an authority which sees in every difference of opinion which arises a Machiavellian manœuvre to deprive the Secretariat of the party of its power and prestige. Therefore from to-day I cease to be a member of the C.P.G.B. Whatever of its policy I can continue to support I shall support to the best of my ability."

Murphy later recalled: "The leadership (still thinking the World Proletarian Revolution was on), was scared of the idea of ‘aiding capitalism to recover’ - the crime of which I myself was accused when proposing that Soviet Russia should be granted credits for the purpose of buying machinery from British engineering factories where masses of engineering workers were unemployed. Instead, therefore, of the Communist Party becoming a party leading a class it became a party of ideologues, interpreting the course of history according to doctrine, and concerned more with loyalty to doctrine than to the living realities of social transformation. It is not subservience to Stalin (though that was bad enough), which accounts for the fantastic gyrations of the C.P.G.B., but the fact that it was beating the air with a false interpretation of the social process and turning itself into a little party of romantic ideologues."

Murphy remained a Marxist but was highly critical of Joseph Stalin. He wrote: "He (Stalin) proclaimed at the beginning of the war that it was a National Patriotic War, not only for survival but also for the liberation of the nations from the grip of Hitlerism. Once survival had been secured, he proceeded from defence to attack and transformed the final stages of the war into a war of imperial conquest in the name of extending the socialist revolution, in Poland, Germany, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Romania."

John Thomas Murphy died in 1965.

Primary Sources

(1) J. T. Murphy, The Workers’ Committee (1917)

One of the most noticeable features in recent trade union history is the conflict between the rank and file of the trade unions and their officials, and it is a feature which, if not remedied, will lead us all into muddle and ultimately disaster. We have not time to spend in abuse, our whole attention must be given to an attempt to understand why our organisations produce men who think in the terms they do, and why the rank and file in the workshops think differently.

A perusal of the history of the labour movement, both industrial and political, will reveal to the critical eye certain tendencies and certain features which, when acted upon by external conditions, will produce the type of persons familiar to us as trade union officials and labour leaders.

Everyone is aware that usually a man gets into office on the strength of revolutionary speeches, which strangely contrast with those of a later date after a period in office. This contrast is usually explained away by a dissertation on the difference between propaganda and administration. That there is a difference between these two functions we readily admit, but that the difference sufficiently explains the change we deny. The social atmosphere in which we move, the common events of every-day life, the people with whom we converse, the struggle to make ends meet, the conditions of labour, all these determine our outlook on life.

(2) J. T. Murphy, The Socialist (November 1918)

1917 saw emerging from the mighty shambles a people dripping with blood but with vision clear and purpose well defined. Imperialism had to go and thrones began to tremble and crowns were kicked into the dust. By the November Revolution of 1917 the working class of Russia sealed for ever the doom of a once mighty empire and set the pace for the working classes of other lands. A new epoch in world history opened then. The war drum of capitalism, whose deep wail had filled the hearts of men with dread, has proved to be the birth pangs of a new order. The social revolution has begun and none can stop it. They who have dwelt in the dark places of the earth have seen a great light and “the peoples’ flag,” stained deep with their blood, now flies where once imperialism’s banners were unfurled. Not yet has the working class of Britain seen fit to take matters in their own hands and settle with the imperialists at home. But the hour is not far distant, and members of the ruling class are apparently anxious to get a blank cheque through their parliamentary institution to prepare the way, on the strength of their apparent victory in Europe, to deal as they think fit with what is called the problem of reconstruction.

A General Election is to be held and we of the Socialist Labour Party call on all Socialists to fight the political fight on the straight ticket of revolutionary Socialism. The Reformist programme, never truly Socialist, can be nothing but a reactionary capitalist programme to-day. The whole of the Socialist movement is lifted right from the platform of negative criticism, on the basis of generalisations from history, to that of having to provide more than criticism. It has to outline a definite and positive alternative to capitalism.

(3) J. T. Murphy, The Communist International (1924)

They betrayed the workers with a lie - a bourgeois lie! They told us we must defend our country and we had no country. They told us that the violation of Belgium, the “tearing of a scrap of paper” was the issue for which we must shed our blood and sacrifice the manhood of a generation. It was a lie - a bourgeois lie. They said it was to “stamp out militarism,” to “save civilisation,” to “establish the rights of small nations,” The bourgeoisie had said the same. And they lied.

We expected lies from the bourgeoisie and from the hacks of the capitalist Press, but from the leaders of Labour, from the leaders of the great multitude without a “fatherland” or “motherland,” we expected the truth and were given lies upon lies.

Mr. Tom Shaw (present Minister of Labour) said at the Labour Party Conference, 1916: “Whatever arrangements we had with France or any other country, the war was due primarily to an unjustifiable attack by Germany upon Belgium.”

Mr. J. H. Thomas at the same Conference said: “He believed that the real cause of this war was not so much the jealousy of Kings or Governments, but that the spirit of militarism had been incalculated in the minds of the people. . . . .”

Mr. Wardle, Chairman of the 1917 Labour Party Conference said in his presidential speech: “I am proud of the fact that the majority of the Labour Party threw itself into the struggle with all the ardour at its command and my one regret has been that this decision has not been unanimous (though we have the satisfaction of knowing that not even the minority desire to see the issue settled by the victory of the Central powers) and that the whole strength of the Party has not been available in a cause which in my opinion embodies every true hope for which we have ever stood and every real aspiration for peace which we have ever given our unflinching adhesion.”

.... We repeat, they saw the war coming. They knew the character of the war and the whole British Labour Movement became divided into three sections. First, there were the Shaws, the Thomas’s, the Clynes, the Wardles, the socialpatriotic leaders who do not wish to abolish capitalism, who are the faithful allies of the capitalists and traitors to the workers in every crisis of capitalism. Second came the word spinners against capitalism who deliver dignified sermons and stifle the mass revolts of the workers, who urge the workers to retreat in a “gentlemanly way” before the will and power of the capitalists whether at war or peace. These are the MacDonalds, the supporters of the Independent Labour Party. Third, comes the very small groups who took their stand upon the fact that “The war was not started by the sinister will of the robber capitalists, although it is fought in their interests, and is not enriching anybody else. The war was the consequences of the development of international capitalism in the course of the last fifty years of its endless combinations and ramifications.” Hence to drop the class war because the capitalist governments desire to continue their politics by military measures is to surrender the working class for the slaughter and perpetuate the rule of capitalism. This they refused to do, and by continuous propaganda, they denounced the war, exposed its character and purpose, seized every opportunity of discontent amongst the workers to lead them into the struggle through strikes and demonstrations as a means of developing the class war out of the imperialist war. Through the activities of the Socialist Labour Party of that period and a section of the British Socialist Party, their activities led to the creation of a mass movement in the form of the Shop Stewards’ and Workers’ Committees. These constituted the sum total of the class war fighters against the Imperialist war, and out of them came the present Communist Party. They saw. They spoke. They translated their words into deeds.

(4) J. T. Murphy, The Errors of Trotskyism (1925)

It is said Comrade Trotsky wanted democracy to come from below, and the Central Committee wanted to introduce it from above. For Comrade Trotsky or anyone else to speak of introducing the Resolutions of the Party Conference from “below,” that is to begin with the locals spreading upwards, is to again forget the first principles of Bolshevik Party organisation, and thereby strengthen the political position of the opponents of the Party. Of what use is it to elect an Executive Committee if the decisions of the Party Congress can be effectively carried through without the election of such a committee? And this is what the proposals amounts to. It finds its echo amongst many industrialists in this country and also amongst reformist Labour leaders. The industrialists plead for more ballots, more referendums, impervious to the fact that they are simply transferring the Parliamentarism of the Labour Party to the industrial arena. The union leaders respond, and the “coming from below” turns out to be more often than not the means for preventing action than securing it.

The industrialists grasp at forms of procedure when the real issue is the organisation of the struggle against reformism due to the fact that the trade unions have yet to be won to the class war line of working class interests. It is this control of working class organisation by leaders who are opposed to the class interests of the workers and refuse to lead the workers in the fight for those interests, that makes it necessary to organise the struggle “from below” in the unions and the Labour Party. But this cannot apply to a revolutionary party based upon the interests of the working class. To apply it to such a party is to utterly demoralise it by the introduction of the reformist forces it exists to destroy. To propose such a course at an important stage in the history of the revolution, when the Party was called upon to make a tremendous strategic move, to adjust itself to an entirely new mileu, as must be the case in the change from war Communism to the NEP, was to endanger the united action of the Party by separating the C.C. from the body of the Party. Obviously if the Party is to undertake an internal transformation at the moment it has to conduct a political manœuvre it must retain unity. Such unity could only be secured under the central direction of the Executive. The high-sounding phrase of “action from below” proves to be nothing more nor less than Menshevik phrase-mongering. It reminds us of the would-be English revolutionary leaders who hide their own weakness in accusing the masses of never being ready and declaim, “They who would be free must themselves strike the blow.” Again - petty bourgeois deviation. How shall we face our October if these things take root in our Party?

(5) J. T. Murphy, The Political Meaning of the Great Strike (1926)

The obvious conclusions to be drawn from this situations and this experience are clear for everyone to see. (1) All actions of the working class movement are political action, and the instruments of the working class struggle, the unions, the Co-ops., the Labour Party itself, can never be led anything other than disaster by men and women who either fail to see, or seeing, refuse to accept the political responsibilities of their actions. (2) The General Strike raised the question of class power and the leaders ran away from it, instead of answering with measures commensurate with the developing situation. (3) To raise the question of the ballot box as an alternative to the General Strike is to dodge the issues and the politics of the issues raised in the course of the struggle, which embraces periods between elections as well as during elections; it fosters illusions as to what can be secured through the ballot box without warning the workers as to the counter plans of the capitalist class to block the way of Socialist legislation; it encourages the belief in the notion that the vote is an alternative to the strike instead of only one of the weapons in the armoury of the workers; in short it ignores completely the realities of the class war as revealed in the General Strike. (4) The failures of the General Council are based upon anti-working class politics which govern the minds of the members of the General Council. The collapse does not signify that there is no need for a General Council; on the contrary the whole experience of the strike shows the need for a real General Council uniting within itself the whole of the trade unions but composed of members governed and disciplined by working class politics. (5) There can be no disciplined action in working class politics without organisation on the basis of working class politics, that is membership of a working class party—the Communist Party. (6) The Communist Party is the only Party which after the General Strike can look the working class in the face confident in the strength of its line of action, before the strike, in the strike and after the strike. The I.L.P. and the Labour Party failed as completely as the General Council.

(6) J. T. Murphy, Workers’ Life (8th March, 1929)

The history of this descent is much more than a battle between Comrade Stalin and Trotsky, it is the history of the triumph of the Communist Party against tendencies and forces misunderstanding, misrepresenting and diverting it from the Marxist-Leninist line of advance.

This struggle did not begin with the death of Comrade Lenin, it began with the formulation of the Communist Party itself, of which Trotsky was an opponent until November, 1917.

This cannot be forgotten now when Trotsky claims that his “attitude towards the revolution, towards the Soviet Power, towards Marxism, and towards Bolshevism remains unchanged.” Compare this with the following statement:—

“During the last six years Soviet Russia has been slipping slowly but surely towards reaction against the October Revolution, and thus preparing for Thermidor (reaction). The clearest sign of this reaction is the ferocious organised destruction of the Left-wing Party.”

Is this “the same attitude to the October Revolution, to Marxism, to Bolshevism”? In this declaration of Trotsky to the Presidium of the Communist International Trotsky repeats the slanders of the Social Democrats and the capitalist Press.

They are slanders to which the most casual examination of the facts relating to soviet economy give the lie.

The rapid expansion of heavy industry, owned and controlled by the Proletarian State, the extension of all State and Co-operative enterprises and the relative decline of private enterprise, simply reduce to absurdity all charges of reactionary tendencies.

But what kind of Bolshevik is this who claims the right of a “Left Wing Party” to exist?

It is axiomatic that there cannot be two Communist Parties in any one country. Trotsky gave his signature to that at the founding of the Communist International.

But there, even in the land of Proletarian dictatorship, where singleness of aim and purpose and control are vital to the very existence of the revolution, he advances the claims of a “Left Wing Party” which is the repudiation of Bolshevism.

(7) J. T. Murphy, letter of resignation of the Communist Party of Great Britain (8th May, 1932)

It is perfectly clear to me after yesterday’s discussion that there is no place for me in the C.P.G.B. at this stage of its history.

After delaying discussion with me on questions raised by me as far back as March 10, 1932, you hold a Political Bureau meeting to which I am not invited; you refrain from circulating the letters which had passed between the Secretariat and myself; you draft a statement as a result of the discussion at this meeting and present it to me for acceptance at the present meeting, winding up your speeches in ultimatum form. You seek to confine discussion to a paragraph in an article although I acknowledged what I considered to be its errors, much more readily than most members of the Political Bureau are prepared to do under similar circumstances. This may be your conception of how to settle differences, but it is not mine.

I was accused of “manœuvring for a platform against the Political Bureau.” The same kind of accusation was made when I differed from the Political Bureau on its estimate of the General Election. You proved to be wrong on that. It may be that you will prove to be wrong again. At any rate I am not prepared to be convinced by ultimatums. Nor am I convinced by your arguments of yesterday afternoon before the categorical demand was made. I see, as yet, no reason to depart from the line indicated in my letters. So you can put your case before the workers and I will put mine. I feel there is no alternative, for after these experiences I have not the slightest confidence in any internal discussion you may initiate.

I am sorry to part company with the party after all these years of service to it, but I decline to go about subordinating myself to a policy I do not conscientiously accept, to be silent on questions which I conscientiously deem important, and subject myself to an authority which sees in every difference of opinion which arises a Machiavellian manœuvre to deprive the Secretariat of the party of its power and prestige.

Therefore from to-day I cease to be a member of the C.P.G.B. Whatever of its policy I can continue to support I shall support to the best of my ability.

(8) J. Shields, The Communist International (15th July, 1932)

The renegades from the ranks of Communism, the camp of the enemies of the working class, have received another recruit in the person of J. T. Murphy, who has deserted from the Communist Party of Great Britain.

On May 8th, 1932, Murphy, who had been a member of the Central Committee of the Party in Britain, addressed a letter to the Political Bureau, which declared: "It is perfectly clear to me . . . that there is no place for me in the C.P.G.B. at this stage of its history... Therefore from to-day I cease to be a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain."

What is "this stage" of the Party’s history which Murphy refers to? It is the very moment when the whole attack of capital against the working class, and, above all, against the Communist Party, is being rapidly developed and takes on a more pronounced form. It is the period when the Party is mobilising the working masses for the struggle against the economic and political offensive of the bourgeoisie. It is the period when the Party is leading a tremendous fight against imperialist war and the danger of intervention menacing the U.S.S.R. Particularly at the present moment, when the struggle needs to be strengthened against the enormously swollen stream of poisonous war propaganda which is being poured out, to uncover and expose the feverish war preparations of the bourgeoisie which they seek to mask in every way, Murphy takes the road of desertion and goes over bag and baggage to the camp of the enemy.

This is no chance occurrence. Almost always, at a time of a sharpening of the class struggle, the opportunist elements in the labour movement have lifted up their heads and have preached the policy of capitulation, the line of counter-revolution and have finally openly deserted from the revolutionary class fight.

(9) The Socialist Standard (June, 1932)

The expulsion of Mr. J. T. Murphy from the Communist Party shows up once more the conflicts between the leaders of that organisation for the control of its confused rank and file. The issue giving rise to the expulsion was no question of Socialist principle or working-class interest. Theoretically it was a conflict of slogans. The Politbureau called upon the workers to “Stop the transport of munitions”; Mr. Murphy preferred to demand “Credits for the Soviet Union!” Rather slender ground for a charge of heresy, one would imagine; but there is probably more in the matter than meets the eye.

As is usual in the Communist Party, the expulsion was carried out dictatorially. The Politbureau expelled Mr. Murphy in answer to his resignation, and informed the membership afterwards. The Communist Party, unlike the S.P.G.B., provides no opportunity for a member to defend himself against a charge before a branch meeting, delegate meeting or Annual Conference. We have, therefore, no means of testing the amount of support Mr. Murphy had among the members of the Party. It is, however, interesting to notice that the fusilade of condemnation of Mr. Murphy in the columns of the Daily Worker contains at least one significant admission. The Working Bureau of the London District Party Committee, “endorsing the decision of the Politbureau,” drew that body’s attention to the “weakness revealed in our ranks by the fact that nowhere within the Party did any comrades appear to recognise Murphy’s wrong line or query his article” (Daily Worker, May 19th).

Mr. Murphy’s slogan could, of course, be adopted by any capitalist wishing to export goods to Russia. Most Liberals and some Conservatives are in favour of such procedure. At the same time, the slogan officially favoured is of the sort likely to appeal to the sentimental anarchists and general strike fanatics, who fondly hug the delusion that the operations of Governments enjoying the political support of the major portion of the workers can be seriously hampered by attempts at minority mass action. The workers and unemployed (unable, as they are, in their present state of disorganisation, to defend their wages and insurance benefits against “economy” cuts) are expected to rise in defence of the Russian Government! Could folly go further?

Mr. Murphy’s lukewarmness is not altogether a mystery. He has for many years been associated with an important munition producing area (i.e., Eastern Sheffield), and working-class electors of Brightside, whose votes he solicited at the last General Election, not being Socialist, can hardly be expected to display enthusiasm over a proposal to curtail their chance of getting or holding a job. They may want capitalism to be administered more favourably to themselves, but there is the rub—they want capitalism! And no one knows that better than Mr. Murphy. From his point of view, full-time production of munitions or anything else for the defence of the Soviet Union, or for the defence of China from Japanese imperialism, or any other old “ism,” would therefore be a much more attractive election cry.

(10) J. T. Murphy, Forty Years Hard — For What? (1958)

We British Marxists who witnessed the 1917 Russian Revolution had more religion than reason in our mode of thinking. Our knowledge of Marxism had led us to a number of assumptions, which we accepted as articles of faith. Among these were a crude assertion of the primacy of ‘matter’ (whose artificial separation from ‘mind’ belongs to the period before the revolution in modern science, to the language of Newtonian rather than of nuclear physics): a doctrinaire picture of the class-struggle which gave us a view of capitalist society in which two classes only remained to fight it out - the capitalist class, owning the means of production, and the class without property, the proletariat: and the expectation that capitalist society was nearing its death agonies as the result of its own inner economic contradictions and the ‘expropriators would be expropriated’. So what was the use of Socialists blethering about a new society idealistically arranged according to their ‘petit-bourgeois’ dreams when the economic laws ‘operating irrespectively of our wills’ showed that the system could not be reformed? The thing was to develop the ‘class consciousness’ of the workers and prepare them for the great day when the capitalist class got what was coming to them as the economic laws inevitably brought their system to its doom.

But, before 1917, the revolutionary socialist parties ‘preparing for the day’ were not conceived as parties of insurrection. Rather did we conceive ourselves (James Connolly said), as ‘John the Baptists of the New Redemption’.

Such were the assumptions of the Marxists before the Russian Revolution drew them together to form the Communist Party. Leaving aside for the moment the scientific validity of ‘Scientific Socialism’, did we who became adherents of Marxism think about these theories scientifically? Not at all. We were disciples, advocates, expounders, missionaries of the ‘Cause’. These theories became the substance of our Faith, containing all we hoped for, enabling us to see what we wished to see. We were subordinating our reasoning to belief as all religionists do, transforming theories into doctrines, interpreting the social transformation taking place before our eyes as the ‘disintegration of capitalism’ despite the fact that life was flouting the basic tenets of our doctrines. Suddenly, the whole Marxist thesis of capitalism bursting itself asunder in the most highly developed and industrialised countries first was knocked sky high, for behold the ‘Ten Days that Shook the World’ were declared by Lenin and the Bolsheviks to be the opening days of the ‘World Proletarian Revolution’. Did we stop in our tracks, ask why we had been forestalled by our new god ‘history’ and query whether the Russian Revolution could be what its leaders claimed it to be? Not at all. We were missionaries of a faith and cared not two hoots whether it was Peter or Paul who led the Proletarian hosts or whether the Revolution began in Jerusalem or Rome.

And that was the condition of Marxism and such was our mode of thinking when we responded to the call of Lenin to form the Communist International. Worry about who started the World Proletarian Revolution? Not on your life! We were in the same state of religious intoxication as the new recruit to the Salvation Army, who, sure that he had been saved from eternal damnation, proclaimed to the thrilled gathering of those already ‘washed in the blood of the Lamb’, ‘I feel so happy I could burst the bloody drum’.

The sequel was the formation of the C.P.G.B. in 1920, on the premise that the World Proletarian Revolution is On, and we must recast our ideas about the nature and role of Revolutionary Socialist Parties. The Communist International was urgently necessary, to function as the general staff of the world revolution. As the revolution swept around the world, producing conditions of civil war and colonial wars of national liberation, Communist Parties must be formed in every country as parties of insurrection. These premises, upon which the Communist International was founded, explain the haste to ‘Bolshevise’ the Marxists of Britain. If you doubt this, read the Manifestos of the 2nd Congress of the C.I., the Conditions of Affiliation, the Resolutions on the formation of Soviets, the role of the Communist Parties and their structure, the resolution on Parliamentarism, etc.

The premise of the ‘World Proletarian Revolution’ was accepted as a political fact and remains so in Communist thinking to this day. Actually, it became the substance of our faith. It appeared to us to be so, and therefore it was so, and all the stirring social upheavals fitted into the pattern of our thinking. When the revolutionary wave subsided to the frontiers of Soviet Russia, did that raise any doubts? Not at all. There will be wave on wave, we said. Meanwhile, we are in a ‘period of partial stabilisation of capitalism’. ‘We’ve got a breathing space,’ said Lenin, in which to consolidate our gains and prepare for the next advance - which simply did not come. Instead, Fascism raised its head. With that fading out of the apparent ‘fact’ of the World Proletarian Revolution, it didn’t fade out of our faith. The General Staff of the Parties ‘On the Road to Insurrection’ still believed they were travelling that road, but ceased to call on the workers of all lands to take arms in hand and overthrow their toppling governments and changed its line in keeping with the ebb tide of World Revolution. The Soviets switched on to the line of ‘Socialism in One Country’, ‘Hands Off Russia’, ‘Defend the Soviet Union’, ‘Collective Security’, ‘United Front from Below’, ‘People’s Front’ and so on - all orchestrated by the General Staff of the Parties of Insurrection.

But the Bolshevisation of the C.P.G.B. went on apace to remodel the party on the principles of democratic centralism, which are principles of a military, insurrectionary party with militaristic and insurrectionary aims. Centralisation of authority is common to all military organisation and is to be tolerated if there is a war on. But if there isn’t a war on, doesn’t that centralisation become transformed into pompous bureaucracy and Blimpian stupidity?

Isn’t the strange history of the C.P.G.B. in its first twenty years, to be explained by the artificiality of its existence, and its illusions rather than its mendacity? The premises for the existence of a party of insurrection did not exist. Lenin’s ‘World Proletarian Revolution’ existed only as the article of faith of the C.I. and its sections. Does not the artificiality of the party’s existence also explain the fantastic record of its relations with the Labour and Socialist movement? At one moment the C.P. wants to "take the leaders by the hand as a preliminary to seizing them by the throat". At the next it wanted affiliation and then it didn’t. We built a Left Movement of fellow travellers in the Labour Party and then we destroyed it. We built a Minority Movement in the trade unions and then liquidated it. Then the Labour Party "is in ruins" and the day of the Mass Communist Party has arrived! That was just after a general election in which the Labour Party polled seven million votes and the Communist Party had polled seventy thousand votes and lost its deposits in almost every constituency it contested. Some ruins! Some mass party! Some clarity! The leadership (still thinking the World Proletarian Revolution was on), was scared of the idea of ‘aiding capitalism to recover’ - the crime of which I myself was accused when proposing that Soviet Russia should be granted credits for the purpose of buying machinery from British engineering factories where masses of engineering workers were unemployed. Instead, therefore, of the Communist Party becoming a party leading a class it became a party of ideologues, interpreting the course of history according to doctrine, and concerned more with loyalty to doctrine than to the living realities of social transformation. It is not subservience to Stalin (though that was bad enough), which accounts for the fantastic gyrations of the C.P.G.B., but the fact that it was beating the air with a false interpretation of the social process and turning itself into a little party of romantic ideologues.

There is no evidence either in this outline of the Communist Party’s history, nor in any of their publications, that the C.P. realised, when it flung itself on the side of Churchill and the Coalition in the course of the war, that by doing so it had changed the premises of its existence from the ‘class war’ to that of social co-operation of all classes. There is not the slightest indication that any of them realised that the theoretical premises of Marxism and Leninism were being flouted by life. With the same religious fervour which had marked it from its inception it plunged into the war of survival, ready and willing to fight in fields, factories and workshops and swim furiously with the tide of life; but cherishing still the hope that after survival they could carry their harvest of recruits into the holy church of the ‘World Proletarian Revolution’. Stalin had this idea too. He proclaimed at the beginning of the war that it was a National Patriotic War, not only for survival but also for the liberation of the nations from the grip of Hitlerism. Once survival had been secured, he proceeded from defence to attack and transformed the final stages of the war into a war of imperial conquest in the name of extending the socialist revolution, in Poland, Germany, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Romania.

While the war of survival was on, the C.P. locked its Bibles of the revolution, in the archives of faith and succeeded in recruiting many thousands to its ranks. As soon as the war was over, did the party of ‘Scientific Socialism’ scientifically examine either its articles of faith or the meaning of its travail up to 1939, or the realities of the great social transformation which the war itself had engendered? No; the scientific mode of thinking is not up their street. They thought only with the doctrines which formed the stuff of their faith, and switched again into the social philosophy euphemistically defined as the ‘class war front’ - when war of any kind can no longer function as the modus vivendi of social living.

That is the key to the loss of membership after the war. It is also the key to the confusion of Khruschev on succeeding Stalin, and the bewilderment he created in the ranks of Communism everywhere. His confusion was created by an attempt to make a fundamental change in policy which living reality demanded, and pattern it within the framework of the social war philosophy of Marx, Lenin and Stalin. Because he could not move a foot in the new direction with Stalin’s heritage of terror on his back, he denounced Stalin, and resurrected Lenin in order to read the transformed world of life through the lenses of outmoded myth. That is the meaning the bewilderment of post-war history everywhere. It is certainly the explanation of the gyrations of Khruschev and the forty years fruitless waste and misdirection of sacrificial energy of the C.P.G.B. It has its origin in the split thinking which divides life into matter and spirit, when in reality it cannot be so divided. This it is which turns social life into social conflict, and turns all men into Dr. Jekylls and Mr. Hydes. With this split in the premises of thought is the subordination of reason to faith and belief. ‘Come reason together freely’, says the commonsense of man, and examine anew the foundations of your faith. For faith which reason does not control breeds stupidity and fanaticism. ‘Socialism’ must free itself from its ‘ism’ characteristics, and stand revealed as a way of life which reason shows to be governed by the principle of social co-operation of all people in social well-being.