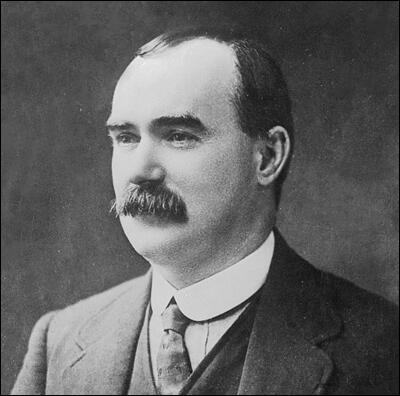

James Connolly

James Connolly was born in Edinburgh in 1868. He joined the British Army and served in Ireland. However, he deserted in 1889 and returned to Scotland where he did a variety of different jobs.

Connolly became a socialist and in 1896 moved to Dublin as an organizer of the Dublin Socialist Society. Later he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party and established The Workers' Republic in 1898. Books by Connolly during this period included Erin's Hope (1897) and The New Evangel (1901).

In 1902 Connolly returned to Edinburgh and helped launch the journal, Socialist, in Edinburgh. Connolly was influenced by the writings of the American radical Daniel DeLeon and published several articles by him in his journal.

Connolly emigrated to the United States in 1903. He established the Irish Socialist Federation and the newspaper, The Harp. In 1905 Connolly joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and worked hard at building up the movement in Newark, New Jersey. He also published several books including Socialism Made Easy (1909), Labour in Irish History (1910) and Labour, Nationality and Religion (1910).

In 1910 Connolly returned to Dublin where he joined the Socialist Party of Ireland. The following year William O'Brien arranged for Connolly to become organizer of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union in Belfast. In 1912 Connolly and James Larkin established the Irish Labour Party.

By 1913 the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union had 10,000 members and had secured wage increases for most of its members. Attempts to prevent workers from joining the ITGWU in 1913 led to a lock-out. Connolly returned to Dublin to help the union in its struggle with the employers. This included the formation of the Irish Citizen Army. Despite Larkin raising funds in England and the United States, the union eventually ran out of money and the men were forced to return to work on their employer's terms.

Connolly took control of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union when James Larkin left for a lecture tour of the United States in October 1914. He also revived his socialist journal, The Workers' Republic, but it was suppressed in February 1915. Later that year he published The Re-Conquest of Ireland (1915).

During the Easter Rising, Connolly's Irish Citizen Army fought alongside the Irish Volunteers under Patrick Pease. Connolly served in the General Post Office during the fighting and was severely wounded.

Father Aloysius (William Patrick Travers) later told Nora Connolly: ."It was a terrible shock to me, I'd been with him that evening and I promised to come to him this afternoon. I felt sure there would be no more executions. Your father was much easier than he had been. I was sure that he would get his first real night's rest. The ambulance that brought you home came for me. I was astonished. I had felt so sure that I would not be needed. For the first time since the Rising, I had locked the doors. And some time after two I was knocked up. The ambulance brought me to your father. Such a wonderful man - such a concentration of mind. They carried him from his bed in an ambulance stretcher down to a waiting ambulance and drove him to Kilmainham Jail. They carried him from the ambulance to the jail yard and put him in a chair. He was very brave and cool. I said to him, 'Will you pray for the men who are about to shoot you' and he said: 'I will say a prayer for all brave men who do their duty. His prayer was 'Forgive them for they know not what they do' and then they shot him. James Connolly died on the 12th of May 1916

Primary Sources

(1) James Connolly, The Workers' Republic (June 1899)

I know it because I read it in the papers. I also know it to be the case because in every country I have graced with my presence up to the present time, or have heard from, the possessing classes through their organs in the press, and their spokesmen upon the platform have been vociferous and insistent in declaring the foreign origin of Socialism.

In Ireland Socialism is an English importation, in England they are convinced it was made in Germany, in Germany it is a scheme of traitors in alliance with the French to disrupt the Empire, in France it is an accursed conspiracy to discredit the army. In Russia it is an English plot to prevent Russian extension towards Asia, in Asia it is known to have been set on foot by American enemies of Chinese and Japanese industrial progress, and in America it is one of the baneful fruits of unrestricted pauper and criminal immigration.

All nations today repudiate Socialism, yet Socialist ideas are conquering all nations. When anything has to be done in a practical direction towards ameliorating the lot of the helpless ones, or towards using the collective force of society in strengthening the hands of the individual it is sure to be in the intellectual armory of Socialists the right weapon is found for the work.

(2) James Connolly, letter in Weekly People (9th April 1904)

It is scarcely possible to take up a copy of the Weekly People of late without realizing from its contents that it and the party are becoming distinctly anti-religious. If a clergyman anywhere attacks socialism the tendency is to hit back, not at his economic absurdities, but at his theology, with which we have nothing to do.

(3) James Connolly, Labour in Irish History (June 1910)

The Irishman frees himself from slavery when he realizes the truth that the capitalist system is the most foreign thing in Ireland. The Irish question is a social question. The whole age-long fight of the Irish people against their oppressors resolves itself in the last analysis into a fight for the mastery of the means of life, the sources of production, in Ireland. Who would own and control the land? The people, or the invaders; and if the invaders, which set of them - the most recent swarm of land thieves, or the sons of the thieves of a former generation?

(4) James Connolly, speech in Glasgow (15th October 1910)

The Socialist question was not a religious question. It was a question to be settled in the mines and factories, not at the altar. The Socialist movement had nothing whatever to do with the next world. It was no concern of their organization whether there was a heaven or a hell, but, if there was a heaven hereafter, it was poor preparation to live in hell here.

(5) James Connolly, speech quoted in Freeman's Journal concerning the formation of the Irish Citizen Army (14th November 1913)

Listen to me, I am going to talk sedition, the next time we are out for a march, I want to be accompanied by four battalions of trained men. I want them to come with their corporals, sergeants and people to form fours. Why should we

not drill and train our men in Dublin as they are doing in Ulster? But I don't think you require any training.

(6) Nora Connolly went to visit her father in Dublin Castle on 9th May 1916. She published her account of the meeting in the book Portrait of a Rebel Father (1935).

On Tuesday I went with mother. There were soldiers on guard at the top of the stairs and in the small alcove leading to Papa's room. They were fully armed and as they stood guard they had their bayonets fixed. In the room there was an R.A.M.C. officer with him all the time. His wounded leg was resting in a cage. He was weak and pale and his voice was very low. Mother asked was he suffering much pain. "No, but I've been court-martialled today. They propped me up in bed. The strain was very great." She knew then that if they had court-martialled him while unable to sit up in bed, they would not hesitate to shoot him while he was wounded. Asked how he had got the wound he said: "It was while I had gone out to place some men at a certain point. On my way back I was shot above the ankle by a sniper. Both bones in my leg are shattered. I was too far away for the men I had just placed to see me and was too far from the Post Office to be seen. So I had to crawl till I was seen. The loss of blood was great. They couldn't get it staunched." He was very cheerful, talking about plans for the future, giving no sign that sentence had been pronounced an hour before we were admitted.

He was very proud of his men. "It was a good clean fight. The cause cannot die now. The fight will put an end to recruiting. Irishmen will now realize the absurdity of fighting for the freedom of another country while their own is enslaved." He praised the women and girls who fought. I told him about Rory (Connolly's son; the boy had been arrested with other rebels but had given a false name and was released along with all other boys under sixteen). "He fought for his country and has been imprisoned for his country and he's not sixteen. He's had a great start in life, hasn't he, Nora?" Then he turned to mother and said: "'There was one young boy, Lillie, who was carrying the top of my stretcher as we were leaving the burning Post Office. The street was being swept continually with bullets from machine- guns. That young lad was at the head of the stretcher and if a bullet came near me he would move his body in such a way that he might receive it instead of me. He was so young-looking, although big, that I asked his age. "I'm just fourteen, sir," he answered. "We can't fail now."

I saw father next on Thursday, May 11, at midnight. A motor ambulance came to the door. The officer said father was very weak and wished to see his wife and eldest daughter. Mama believed the story because she had seen him on Wednesday and he was in great pain and very weak, and he couldn't sleep without morphine. Nevertheless she asked the officer if they were going to shoot him. The officer said he could tell her nothing. Through dark, deserted sentry-ridden streets we rode. I was surprised to see about a dozen soldiers encamped outside Papa's door. There was an officer on guard inside the room. Papa turned his head at our coming.

"Well, Lillie, I suppose you know what this means?"

"Oh, James, it's not that - it's not that."

"Yes, Lillie. I fell asleep for the first time tonight and they wakened me at eleven and told me that I was to die at dawn."

Mamma broke down and laid her head on the bed and sobbed heartbreakingly. Father patted her head and said: "Don't cry, Lillie, you'll unman me."

"But your beautiful life, James. Your beautiful life!" she sobbed.

"Well, Lillie, hasn't it been a full life and isn't this a good end" I was also crying. "Don't cry, Nora, there's nothing to cry about."

"I won't cry. Papa," I said.

"He patted my hand and said: "That's my brave girl."

"He tried to cheer Mama by telling her of the man who had come into the Post Office during the Rising to try and buy a penny stamp. "I don't know what Dublin's coming to when you can't buy a stamp at the Post Office."

The officer said: "Only five minutes more." Mama was nearly overcome - she had to be given water. Papa tried to clasp her in his arms but he could only lift his head and shoulders from the bed. The officer said: "Time is up." Papa turned and said good-bye to her and she could not see him. I tried to bring Mama away but I could not move her. The nurse came forward and helped her away. I ran back and kissed Papa again. "Nora, I'm proud of you." Then the door was shut and I saw him no more.

(7) Father Aloysius (William Patrick Travers), in conversation with Nora Connolly in May 1916.

It was a terrible shock to me, I'd been with him that evening and I promised to come to him this afternoon. I felt sure there would be no more executions. Your father was much easier than he had been. I was sure that he would get his first real night's rest. The ambulance that brought you home came for me. I was astonished. I had felt so sure that I would not be needed. For the first time since the Rising, I had locked the doors. And some time after two I was knocked up. The ambulance brought me to your father. Such a wonderful man - such a concentration of mind. They carried him from his bed in an ambulance stretcher down to a waiting ambulance and drove him to Kilmainham Jail. They carried him from the ambulance to the jail yard and put him in a chair. He was very brave and cool. I said to him, "Will you pray for the men who are about to shoot you" and he said: "I will say a prayer for all brave men who do their duty." His prayer was "Forgive them for they know not what they do" and then they shot him.