Industrial Workers of the World

In 1905 representatives of 43 groups who opposed the policies of American Federation of Labour, formed the radical labour organisation, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The IWW's goal was to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class. Its motto was "an injury to one is an injury to all".

At first its main leaders were William Haywood, Vincent Saint John, Daniel De Leon and Eugene V. Debs. Other important figures in the movement included Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Lucy Parsons, Hubert Harrison, Carlo Tresca, Anna Louise Strong, Joseph Ettor, Arturo Giovannitti, James P. Cannon, William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, Joe Haaglund Hill, Tom Mooney, Harry Bridges, Floyd B. Olson, James Larkin, James Connolly, Roger Nash Baldwin, Frank Little and Ralph Chaplin.

Soon after the IWW was formed William Haywood was charged with taking part in the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho. Steunenberg was much hated by the trade union movement after using federal troops to help break strikes during his period of office. Over a thousand trade unionists and their supporters were rounded up and kept in stockades without trial.

James McParland, from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was called in to investigate the murder. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire.

McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named Hayward and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Charles Darrow, a man who specialized in defending trade union leaders, was employed to defend William Haywood, Charles Moyer and George Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Harry Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry. During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Haywood, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard and were all acquitted.

Many unions refused to accept immigrant workers. This was especially a problem for Jewish and Irish immigrants. This was not true of the Industrial Workers of the World and as a result many of its members were first and second generation immigrants. Several immigrants such as Mary 'Mother' Jones, Hubert Harrison, Carlo Tresca, Arturo Giovannitti and Joe Haaglund Hill became leaders of the organization.

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

In 1908 the Wobblies, as they became known, split into two factions. The group headed by Eugene V. Debs advocated political action through the Socialist Party and the trade union movement, to attain its goals. The other faction led by William Haywood, and believed that general strikes, boycotts and even sabotage to achieve its objectives. Haywood's views prevailed and Debs, and others who thought like him, left the organisation.

As James Cannon pointed out: "At the second convention of the IWW in 1906, St. John headed the revolutionary syndicalist group, which combined with the SLP elements to oust Sherman, a conservative, as president and establish a new administration in the organization with a revolutionary policy. He became the general organizer under the new administration, breaking with the WFM on the withdrawal of the latter body and giving his whole allegiance to the IWW." Vincent Saint John now became General Secretary of the Industrial Workers of the World.

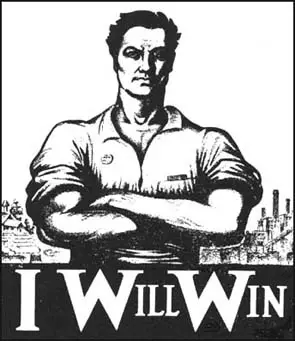

Solidarity (4th August, 1917)

Activists in the IWW such as William Haywood, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Carlo Tresca, Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti, were involved in two major industrial disputes, the Lawrence Textile Strike (1912) and the Paterson Silk Industry Strike (1913). At this time the Industrial Workers of the World had a membership of over 100,000 members.

In 1913 William Haywood replaced Vincent Saint John as secretary-treasurer of the Industrial Workers of the World. By this time, the IWW had 100,000 members. In 1913 Joe Haaglund Hill helped to organize a successful strike at the United Construction Company. During this dispute Hill stayed with some friends in Salt Lake City. While he was there, John G. Morrison, a former policeman, and his son, Arling, were shot dead by two masked gunman in his grocery shop. A few weeks before the murder, Morrison had told a journalist that he had recently been threatened with a revenge attack because of an incident while he was in the police force.

After the shooting, police discovered two men trying to board a departing train at a railroad station near the store. According to the official report, officers Crosby and Hendrickson had to "empty their guns" to prevent the two men from escaping. The men were taken into custody and identified as C.E. Christensen and Joe Woods, two men with arrest warrants in Prescott, Arizona for robbery.

On the night of the murder, 10th January, 1914, Joe Haaglund Hill visited a doctor with a bullet wound in his left lung. Hill claimed he had been shot in a quarrel over a woman. Noting that the bullet had gone clean through the body, the doctor reported Hill's visit to the police. They already knew about Hill's trade union activities and decided to arrest him. Hill refused to say how he got the wound. As a witnesses standing outside Morrison's store claimed that he heard one of the murderers say: "Oh, God, I'm shot." Hill was charged with the murder of Morrison and Christensen and Woods were released from custody.

The police chief of San Pedro, who had once held Hill for thirty days on a charge of "vagrancy" because of his efforts to organize longshoremen, wrote to the Salt Lake City police: "I see you have under arrest for murder one Joseph Hillstrom. You have the right man... He is certanly an undesirable citizen. He is somewhat of a musician and writer of songs for the IWW songbook."

Leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World argued that Joe Haaglund Hill had been framed as a warning to others considering trade union activity. Even William Spry, the Republican governor of Utah admitted that he wanted to use the case to "stop street speaking" and to clear the state of this "lawless elements, whether they be corrupt businessmen, IWW agitators, or whatever name they call themselves"

At Hill's trial in Salt Lake City none of the witnesses were able to identify Hill as one of the murders. This included thirteen-year-old Merlin Morrison, who witnessed the killing of her father and brother. The bullet that hit Hill was not found in the store. Nor was any of Hill's blood. As no money was taken and one of the gunman was heard to say: "We've got you now", the defence argued that it was a revenge killing. However, Hill, who had no previous connection with Morrison, was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death.

Franklin Rosemont has argued: "Nearly all historians have come to recognize as one of the worst travesties of justice in American history. After a trial riddled with biased rulings, suppression of important defense evidence, and other violations of judicial procedure characteristic of cases involving labor radicals, Hill was convicted and sentenced to death."

Bill Haywood and the IWW launched a campaign to halt the execution. Elizabeth Flynn visited Hill in prison and was a leading figure in the attempts to force a retrial. In July, 1915, 30,000 members of Australian IWW sent a resolution calling on Governor William Spry to free Hill. Similar resolutions were passed at trade union meetings in Britain and other European countries. Woodrow Wilson also contacted Spry and asked for a retrial. This was refused and plans were made for Hill's execution by firing-squad on 19th November, 1915.

When he heard the news, Joe Haaglund Hill sent a message to Haywood saying: "Goodbye Bill. I die like a true blue rebel. Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize." He also asked Haywood to arrange his funeral: "Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don't want to be found dead in Utah." Hill last act before his death was to write the poem, My Last Will.

An estimated 30,000 people attended Hill's funeral. The instructions left in Hill's last poem were carried out: "And let the merry breezes blow/My dust to where some flowers grow/Perhaps some fading flower then/Would come to life and bloom again." Hill's ashes were put into small envelopes and on May Day, 1916, were scattered to the winds in every state of the union. This ceremony also took place in several other countries.

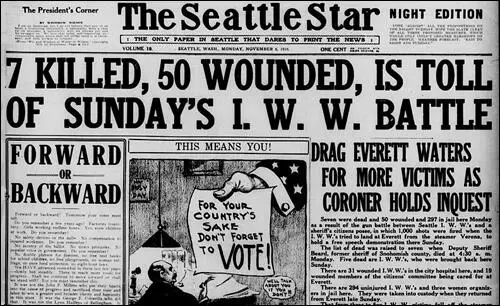

In early November, 1916, had arrived in Everett, Washington. to give support for striking shingle workers who had been involved in a five-month dispute. Once there, vigilantes employed by local businessmen had beaten them up with axe handles and run them out of town.

On the 5th November about 300 IWW members met at the IWW Hall in Seattle and then marched down to the docks where they boarded the steamers Verona and Calista which then headed north to Everett. More than 200 vigilantes (citizen deputies) under the authority of Sheriff Donald McRae, met the ships when they sailed into the dock. McRae drew his pistol, told them he was the sheriff, he was enforcing the law, and they couldn't land. The vigilantes then opened fire on the IWW. Passengers aboard the Verona rushed to the opposite side of the ship, nearly capsizing the vessel. The ship's rail broke and a number of passengers were ejected into the water, some drowned as a result but how many is not known, or whether persons who'd been shot also went overboard. Over 175 bullets pierced the pilot house alone.

Two citizen deputies were killed with about 18 others wounded, including Sheriff McRae. The two deputies that were shot were actually shot in the back by fellow deputies; their injuries were not caused by IWW gunfire. It is estimated that about 12 members of the IWW officially were killed.

Seventy-four Wobblies were arrested as a direct result of the Everett Massacre including IWW leader Thomas H. Tracy. They were charged with the murder of the two deputies. After a two-month trial, Tracy was acquitted by a jury on May 5, 1917. Shortly thereafter, all charges were dropped against the remaining 73 defendants and they were released from jail.

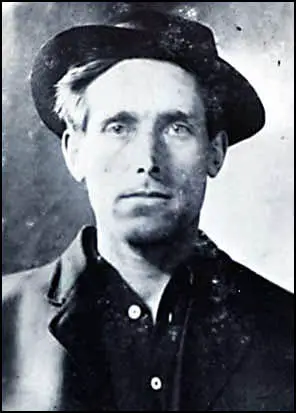

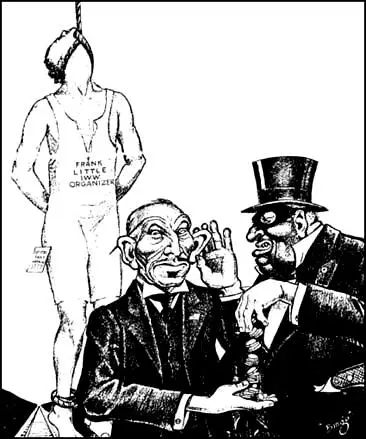

In the summer of 1917, Frank Little was helping organize workers in the metal mines of Montana. This included leading a strike of miners working for the Anaconda Company. In the early hours of 1st August, 1917, six masked men broke into Little's hotel room in Butte. He was beaten up, tied by the rope to a car, and dragged out of town, where he was lynched. A note: "First and last warning" was pinned to his chest. No serious attempt was made by the police to catch Little's murderers. It is not known if he was killed for his anti-war views or his trade union activities.

Solidarity Magazine (11th August, 1917)

The lawyer representing the Anaconda Company said a few days later: "These Wobblies, snarling their blasphemies in filthy and profane language; they advocate disobedience of the law, insults to our flag, disregard of all property rights and destruction of the principles and institutions which are the safeguards of society.... Why, Little, the man who was hanged in Butte, prefaced his seditious and treasonable speeches with the remark that he expected to be arrested for what he was going to say... The Wobblies... have invariably shown themselves to be bullies, anarchists and terrorists. These things they do openly and boldly."

Lillian Hellman claimed in Scoundrel Time (1976) that Dashiell Hammett, while working for the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Montana, turned down an offer of $5,000 to "do away with" Frank Little. Hellman recalled: "Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer (to kill Frank Little) so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder, and the fact that Frank Little was lynched with three other men in what was known as the Everett Massacre must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I think I can date Hammett's belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little's murder."

William Haywood and the IWW opposed the United States becoming involved in the First World War. However, Haywood did not agitate against it nor forbid members to comply with the draft. Nevertheless, politicians and employers' associations attacked the IWW as disloyal and dangerous. In a series of raids resulted in the indictment of Haywood and most of the union's leadership under the Espionage Act. After a long trial in Chicago, Haywood was sentenced to a fine of $20,000 and twenty years' imprisonment.

As Howard Zinn pointed out in his book, A People's History of the United States (1980): "In early September 1917, Department of Justice agents made simultaneous raids on forty-eight IWW meeting halls across the country, seizing correspondence and literature that would become courtroom evidence. Later that month, 165 IWW leaders were arrested for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes. One hundred and one went on trial in April 1918; it lasted five months, the longest criminal trial in American history up to that time. The judge sentenced Haywood and fourteen others to twenty years in prison; thirty-three were given ten years, the rest shorter sentences. They were fined a total of $2,500,000. The IWW was shattered."

In March 1921, William Haywood jumped bail and fled to the Soviet Union, while most of his co-defendants languished in prison. As Joseph R. Conlin has pointed out: "IWW morale was shattered. Although individuals remembered him affectionally and excused his action without justifying it, his influence on the American Left had all but vanished."

After the war leaders of the IWW were harassed by the police and suffered legal prosecutions. One member was actually taking from a prison and lynched. This approach was highly effective and by 1925 membership had declined dramatically.

Primary Sources

(1) William Haywood, speech made at the convention where the Industrial Workers of the World was formed (27th June, 1905)

The American Federation of Labor, which presumes to be the labor movement of this country, is not a working-class movements. There are organizations that are affiliated with the American Federation of Labor which prohibit the initiation of a colored man; that prohibit the conferring of the obligation on foreigners. What we want to establish at this time is a labor organization that will open wide its doors to every man that earns his livelihood either by his brain or his muscle.

(2) Daniel De Leon, speech at the Industrial Workers of the World convention in Chicago (27th June, 1905)

The aspiration to unite the workers upon the political field is an aspiration in line and in step with civilization. Civilized man, when he argues with an adversary, does not start with clenching his fist and telling him, 'smell this bunch of bones'. He does not start by telling him, 'feel my biceps'. He begins by arguing; physical force by arms is the last resort. That is the method of the civilized man, and the method of civilized man is the method of civilized organization. The barbarian begins with physical force; the civilized man ends with that, when physical force is necessary. Civilized man will always here in America give a chance to peace; he will, accordingly, proceed along the lines that make peace possible. But civilized man, unless he is a visionary, will know that unless there is Might behind your Right, your Right is something to laugh at. And the thing to do, consequently, is to gather behind the ballot, behind that united political movement, the Might which is alone able, when necessary, to 'take and hold'. Without the working people are united on the political field; without the delusion has been removed from their minds that any of the issues of the capitalist class can do for them permanently, or even temporarily; without the working people have been removed altogether from the mental thralldom of the capitalist class, from its insidious influence, there is no possibility of your having those conditions under which they can really organize themselves economically in such a way as to 'take and hold'. And after those mental conditions are generally established, there needs something more than the statement to 'take and hold'; something more than a political declaration, something more than the capitalist political inspectors to allow this or that candidate to filter through. You then need the industrial organization of the working class, so that if the capitalist should be foolish enough in America to defeat, to thwart the will of the workers expressed by the ballot - I do not say 'the will of the workers, as returned by the capitalist election inspectors', but the will of the people as expressed at the ballot box - then there will be a condition of things by which the working class can absolutely cease production, and thereby starve out the capitalist class, and render their present economic means and all their preparations for war absolutely useless.

(3) Herbert Croly, The Promise of American Life (1909)

The most serious danger to the American democratic future which may issue from aggressive and unscrupulous unionism consists in the state of mind of which mob-violence is only one expression. The militant unionists are beginning to talk and believe as if they were at war with the existing social and political order - as if the American political system was as inimical to their interests as would be that of any European monarchy or aristocracy.

Whether this aggressive unionism will ever become popular enough to endanger the foundations of the American political and social order, I shall not pretend to predict. The practical dangers resulting from it at any one time are largely neutralized by the mere size of the country and its extremely complicated social and industrial economy. The menace it contains to the nation as a whole can hardly become very critical as long as so large a proportion of the American voters are land-owning farmers. But while the general national well-being seems sufficiently protected for the present against the aggressive assertion of the class interests of the unionists, the local public interest of particular states and cities cannot be considered as anywhere near so secure; and in any event the existence of aggressive discontent on the part of the unionists must constitute a serious problem for the American legislator and statesman.

The unionist leaders frequently offer verbal homage to the great American principle of equal rights, but what they really demand is the abandonment of that principle. What they want is an economic and political order which will discriminate in favor of union labor and against non-union labor; and they want it on the ground that the unions have proved to be the most effective agency on behalf of the economic and social amelioration of the wage-earner. The unions, that is, are helping most effectively to accomplish the task, traditionally attributed to the American democratic political system - the task of raising the general standard of living; and the unionists claim that they deserve on this ground recognition by the state and active encouragement. Obviously, however, such encouragement could not go very far without violating both the Federal and many state constitutions - the result being that there is a profound antagonism between our existing political system and what the unionists consider to be a perfectly fair demand. Like all good Americans, while verbally asking for nothing but equal rights, they interpret the phrase so that equal rights become equivalent to special rights.

(4) Paul Kellogg, Immigration and the Minimum Wage (1913)

My own feeling is that immigrants bring us ideals, cultures, red blood, which are an asset for America or would be if we gave them a chance. But what is undesirable, beyond all peradventure, is our great bottom-lands of quick-cash, low-income employments in which they are bogged. we suffer not because the immigrant comes with a cultural deficit, but because the immigrant workman brings to America a potential economic surplus above a single man's wants, which is exploited to the grave and unmeasured injury to family and community among us.

Petty magistrates and police, state militia and the courts - all these were brought to bear by the great commonwealth of Massachusetts, once the Lawrence strikes threatened the public peace. But what had the great commonwealth of Massachusetts done to protect the people of Lawrence against the insidious canker of subnormal wages which were and are blighting family life? Nor have the trade-unions met any large responsibility toward unskilled labor. Through apprenticeship, organization, they have endeavored to keep their own heads above the general level.

Common labor has been left as the hindmost for the devil to take. For the most part common laborers have had to look elsewhere than to the skilled crafts for succor. They have had it held out to them by the Industrial Workers of the World, which stands for industrial organization, for one big union embracing every man in the industry, for the mass strike, for the benefits to the rank and file here and now, and not in some far-away political upheaval.

(5) The Appeal to Reason journal reported on attempts by Frank Little to recruit members for the Industrial Workers of the World in California (11th February, 1911)

There are about one hundred I.W.W. men in jail now with different charges, but all are arrested for the same offense. Only a few of the I.W.W. men have been tried. Some of the best speakers were tried and convicted of vagrancy, by juries of business men. Four of them got six months apiece, although they proved that they were not vagrants. Many of the boys have been imprisoned for fifty-one days, today, without trial. This happened not in Russia, but in sunny California. Frank Little was arrested on the charge of vagrancy.

Frank Little was arrested on the charge of vagrancy. Frank is one of the 94 I.W.W. men confined in a bull pen, 47 x 28 feet. The officers of the state board of health say that there is air enough in the pen for 5 men. Most of the men confined in the bull pen have been out in the open air only once or twice since they were arrested. A good many of the men have been in there 53 days today.

(6) Helen Keller, The Liberator (1918)

On August 1st, of 1917, in Butte, Montana, a cripple, Frank Little, a member of the Executive Board of the IWW, was forced out of bed at three o’clock in the morning by masked citizens, dragged behind an automobile and hanged on a railroad trestle. Were the offenders punished? No. A high government official has publicly condoned this murder, thereby upholding lynch-law and mob rule.

(7) Viola Gilbert Snell, To Frank Little ( 25th August, 1917)

Traitor and demagogue,

Wanton breeder of discontent -

That is what they call you -

Those cowards, who condemn sabotage

But hide themselves

Not only behind masks and cloaks

But behind all the armoured positions

Of property and prejudice and the law.

Staunch friend and comrade,

Soldier of solidarity -

Like some bitter magic

The tale of your tragic death

Has spread throughout the land,

And from a thousand minds

Has torn the last shreds of doubt

Concerning Might and Right.

Young and virile and strong -

Like grim sentinels they stand

Awaiting each opportunity

To break another

Of slavery's chains.

For whatever stroke is needed.

They are preparing.

So shall you be avenged.

(8) Arthuro Giovannitti, Hanged at Midnight (2nd September, 1917)

Six men drove up to his house at midnight, and woke the poor woman who kept it,

And asked her: "Where is the man who spoke against war and insulted the army?"

And the old woman took fear of the men and the hour, and showed them the room where he slept,

And when they made sure it was he whom they wanted, they dragged him from his bed with blows, tho' he was willing to walk,

And they fastened his hands on his back, and they drove him across the black night,

And there was no moon and no star and not any visible thing, and even the faces of the men were eaten with the leprosy of the dark, for they were masked with black shame,

And nothing showed in the gloom save the glow of his eyes and the flame of his soul that scorched the face of Death.

(9) Lillian Hellman, Scoundrel Time (1976)

Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer (to kill Frank Little) so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder, and the fact that Frank Little was lynched with three other men in what was known as the Everett Massacre must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I think I can date Hammett's belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little's murder.

(10) Diane Johnson, The Life of Dashiell Hammett (1984)

It was in a boardinghouse in Butte, Montana, in 1917 that the owner, Mrs. Nora Byrne, was awakened one night by voices in the room next to hers, room 30, men's voices saying there must he some mistake here, and then feet in the hall, then men at her door, pushing it open, and Mrs. Byrne, having jumped out of bed, held her door with all her strength as some men with guns pushed it in anyway. They held the gun on her, saying, "Where is Frank Little?" and she told them. Then they went away again, and kicked down the door of room 32 and went in and woke the man sleeping there, who made no outcry or objection and demanded no explanation. Because he had a broken leg, they had to carry him out.

Then, in the morning, he was found hanging from the trestle with a warning to others pinned to his underwear. Some people said his balls had been cut off. The warning came from the Montana vigilantes, though it was hard to see what the citizens of Montana stood to gain from the death of this poor man. Only the mine owners stood to gain from the death of this agitator, a Wobbly. Wobblies were stirring up a lot of trouble among the miners at Butte.

"These Wobblies," said the mine owner's lawyer a few days later, "snarling their blasphemies in filthy and profane language; they advocate disobedience of the law, insults to our flag, disregard of all property rights and destruction of the principles and institutions which are the safeguards of society." He was trying to show that Mr. Little had brought his lynching on himself. "Why, Little, the man who was hanged in Butte, prefaced his seditious and treasonable speeches with the remark that he expected to be arrested for what he was going to say." Perhaps he had not expected, however, to he hanged, but what were decent Americans to do with such rascals?

The mine owner's lawyer, noticing no contradiction, inconsistency or irony, proclaimed that the Wobblies "have invariably shown themselves to be bullies, anarchists and terrorists. These things they do openly and boldly," unlike (he did not add) all the decent American vigilantes who came masked by night. The young Hammett, in Montana at the time, noticed the ironies and inconsistencies with particular interest because men had come to him and to other Pinkerton agents and had proposed that they help do away with Frank Little. There was a bonus in it, they told him, of $5,000, an enormous sum in those days.

Hammett's inclinations had probably always been on the side of law and order. His father had once been a justice of the peace and always went to the law when necessary with confidence, for instance, when his buggy was damaged by the potholes on the public road; and he worked for a lock-and-safe company, and at other times as a watchman or a guard. There was thus in the family a brief for caring about the property of others, putting oneself at risk so that things in general should be safe and secure.

But at some moment - perhaps at the moment he was asked to murder Frank Little or perhaps at the moment that he learned that Little had been killed, possibly by other Pinkerton men - Hammett saw that the actions of the guards and the guarded, of the detective and the man he's stalking, are reflexes of a single sensibility, on the fringe where murderers and thieves live. He saw that he himself was on the fringe or might be, in his present line of work, and was expected to be, according to a kind of oath of fealty that he and other Pinkerton men took.

He also learned something about the lives of poor miners, whose wretched strikes the Pinkerton people were hired to prevent, and about the lies of mine owners. These things were to sit in the back of his mind.

And just as he learned about the lot of poor miners, and about the aims of trade unions, so at some point he learned about the rich. He saw their houses - maybe as a Pinkerton man, or maybe it was back in Baltimore that he noticed the furniture and pictures in rich people's houses, different from the crowded parlor on North Stricker Street, or from the boardinghouses and cheap hotels he stayed in.

(11) Philip Randolph, The Messenger (July, 1919)

The IWW is the only labor organization in the United States which draws no race or color line. There is another reason why Negroes should join the IWW. The Negro must engage in direct action. He is forced to do this by the Government. When the whites speak of direct action, they are told to use their political power. But with the Negro it is different. He has no political power. Therefore the only recourse the Negro has is industrial action, and since he must combine with those forces which draw no line against him, it is simply logical for him to draw his lot with the Industrial Workers of the World.

(12) Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (1980)

In early September 1917, Department of Justice agents made simultaneous raids on forty-eight IWW meeting halls across the country, seizing correspondence and literature that would become courtroom evidence. Later that month, 165 IWW leaders were arrested for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes. One hundred and one went on trial in April 1918; it lasted five months, the longest criminal trial in American history up to that time.

The judge sentenced Haywood and fourteen others to twenty years in prison; thirty-three were given ten years, the rest shorter sentences. They were fined a total of $2,500,000. The IWW was shattered. Haywood jumped bail and fled to revolutionary Russia, where he remained until his death ten years later.

(13) Time Magazine (23rd July, 1923)

In Los Angeles, 27 members of the Industrial Workers of the World were convicted of criminal syndicalism and sentenced to from one to 14 years in San Quentin prison. Seventeen other " wobblies," as the IWW are known, had previously been convicted.

Next day longshoremen held a meeting and went out on strike as a protest. On the second day of the strike ship owners declared that only 200 men were out, the strike a fizzle.

The IWW are making an effort to gain a firm foothold on the Pacific Coast. The July 1 number of The Marine Worker (published free of charge by the Marine Transport Workers' International Union, No. 510; address Box 69, Station D, New York City) gave some indication of the propaganda which the IWW are carrying on in Los Angeles. It is published about 25% in Spanish and carries such slogans as: Boycott all California-made Goods and Motion Pictures. You Cannot Fight the Boss and Booze at the Same Time. Be Like a Mule and Kick if Conditions Don't Suit You; Remember: "An Injury to One is an Injury to All" (motto of the IWW).

(14) Time Magazine (3rd September, 1923)

The Industrial Workers of the World turned loose another threat. They plan an "early drive on Sacramento," the object of which is to teach that city a "lesson" for the prosecution of IWW members under the criminal syndicalism law of California. The Wobblies would start a "reign of terror." The members would invade the city, fill the jails, start a free speech campaign, parade to the detriment of Sacramento's pride and complacence.

The cause of the threat was the issuance of an injunction by the Superior Court of Sacramento County forbidding the I. W. W. to act as an organization or as its officers and members. In view of previous I. W. W. threats of a similar nature, Sacramento has probably not much to fear.

(15) Mary Heaton Vorse, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, The Nation (17th February, 1926)

She began this amazing record by getting arrested on a street corner when she was fifteen. Her father was arrested with her. He never has been arrested since. It was only the beginning for her.

The judge inquired, "Do you expect to convert people to socialism by talking on Broadway?"

She looked up at him and replied gravely, "Indeed I do."

The judge sighed deeply in pity. "Dismissed," he said.

Joe O'Brien gives me a picture other at that time. He was sent to cover the case of these people who had been arrested for talking socialism on Broadway. He expected to find a strong-minded harpy. Instead he found a beautiful child of fifteen, the most beautiful girl he had ever seen. A young Joan of Arc is what she looked like to him with her dark hair hanging down her back and her blue Irish eyes ringed with black lashes. That was how she entered the Labor movement. Since then she has never stopped.

Presently she joined the I.W.W., which was then in its golden age. Full of idealism, it swept the Northwest. They had free-speech fights everywhere. The authorities arrested them and more came. They crammed the jails to bursting.

"In one town," said Elizabeth, "there were so many in jail that they let them out during the day. We outside had to feed them. Every night they went back to jail. At last the wobblies decided that when the jail opened they would not come out. People came from far and near to see the wobblies who wouldn't leave jail."

This part of her life, organizing and fighting the fights of the migratory workers of the West, is the part other life that she likes most. Her marriage did not affect her activities. The arrival of her son did. His birth closed this chapter other life.

My first sight of her was in Lawrence in the big strike of 1912. I arrived just after the chief of police had refused to allow the strikers to send their children to the workers' homes in other towns. There had been a riot at the railway station. Children had been jostled and trampled. Women fainted. The town was under martial law. Ettor and Giovannitti were in jail for murder as accessory before the fact.

I walked with Bill Haywood into a quick-lunch restaurant. "There's Gurley," he said. She was sitting at a lunch counter on a mushroom stool, and it was as if she were the spirit of this strike that had so much hope and so much beauty. She was only about twenty-one, but she had gravity and maturity. She asked me to come and see her at her house. She had gone on strike, bringing with her her mother and her baby.

There was ceaseless work for her that winter. Speaking sitting with the strike committee, going to visit the prisoner in jail, and endlessly raising money. Speaking, speaking, speaking, taking trains only to run back to the town that was ramparted by prison-like mills before which soldiers with fixed bayonets paced all day long. Almost every night when we didn't dine in the Syrian restaurant we dined in some striker's home, very largely among the Italians. It seemed to me I had never met so many fine people before. I did not know people could act the way those strikers could in Lawrence. Every strike meeting was memorable - the morning meetings in a building quite a way from the center of things, owned by someone sympathetic to the strikers, the only place they were permitted to assemble. The soup kitchen was out here and here groceries were also distributed and the striking women came from far and near. They would wait around for a word with Gurley or with Big Bill. In the midst of this excitement Elizabeth moved calm and tranquil. For off the platform she is a very quiet person. It was as though she reserved her tremendous energy for speaking.

The Paterson textile strike followed Lawrence. In Lawrence there was martial law and militia. It was stern, cruel, and rigorous. The Paterson authorities were all of that and besides they were petty, niggling, and hectoring. Arrests were many. Jail sentences were stiff and given for small cause. Elizabeth was also arrested, but set free again The Paterson strike of all the strikes stands out in her memory. She got to know the people, and their courage and spirit were things that none of us who were there could ever forget.

The strike on the Mesaba Range was the end of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn's activities as organizer in the I.W.W. Just after the Espionage Act had been passed it happened that we went to the theater together. "If I were in the I.W.W. now," she said, "whether I opened my mouth or didn't I would surely be arrested. It's rather nice to draw a long breath." Next day she was arrested just the same. She was one of the 166 people associated with the I.W.W. indicted for conspiracy.

Defense work was no new thing to her, and from 1918 until recently her major activities have been getting political prisoners out of jail. And since 1921 she has concentrated on the Sacco-Vanzetti case. There has been constant work, there have been arrests, there has been her preoccupation with comrades in jail for their opinions. She comes out of her first twenty years in the labor movement undimmed and undiscouraged.