Eugene V. Debs

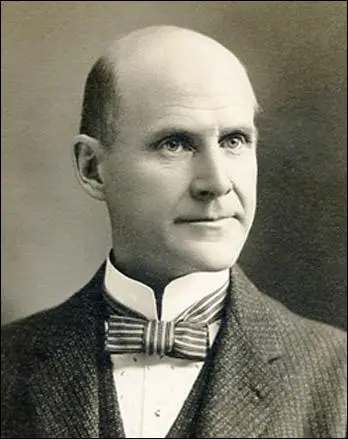

Eugene Victor Debs was born in in Terre Haute, Indiana, on 5th November, 1855. His parents, Jean Daniel and Marguerite Marie Bettrich Debs, both immigrated to the United States from Colmar, in the Alsace region of France.

Debs left school at the age of 14 and found work as a painter in a railroad yards. He became a railroad fireman in 1870 and soon afterwards became active in the trade union movement. Debs worked as editor of the Locomotive Firemen's Magazine, before being elected national secretary of Brotherhood of Locomotive Fireman in 1880. Debs, a member of the Democratic Party, was elected to the Indiana Legislature in 1884.

In 1893 Debs was elected the first president of the American Railway Union (ARU). In 1894 George Pullman, the president of the Pullman Palace Car Company, decided to reduced the wages of his workers. When the company refused arbitration, the ARU called a strike. Starting in Chicago it spread to 27 states. John Swinton, a journalist working for the New York Times, argued that as an orator, Debs was comparable to Abraham Lincoln: "It seemed to me that both men were imbued with the same spirit. Both seemed to me as men of judgment, reason, earnestness and power. Both seemed to me as men of free, high, genuine and generous manhood. I took to Lincoln in my early life, as I took to Debs a third of a century later."

The attorney-general, Richard Olney, sought an injunction under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act against the Pullman Strike. As a result, of Olney's action, Eugene Debs was arrested and despite being defended by Clarence Darrow, was imprisoned. The case came before the Supreme Court in 1895. David Brewer spoke for the court on 27th May, explaining why he refused the American Railway Union's appeal. This decision was a great set-back for the trade union movement.

While serving his time in Woodstock Prison he read the works of Karl Marx. By the time he left prison in 1895 Debs became a socialist and believed that capitalism should be replaced by a new cooperative system. Although he advocated radical reform, Debs was opposed to the revolutionary violence supported by some left-wing political groups.

In 1897 Debs joined with Victor Berger and Ella Reeve Bloor to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Other members included Carl Sandburg, Frederic Heath, Margaret Haile, Job Harriman, Max S. Hayes, Algernon Lee, William Mailly and Seymour Stedman. The following year two members of the party were elected to the Massachusetts legislature.

Debs was the SDP's candidate in 1900 Presidential Election but received only 87,945 votes (0.6) compared to William McKinley (7,228,864) and William Jennings Bryan (6,370,932). The following year the SDP merged with Socialist Labor Party to form Socialist Party of America. Leading figures in this party included Debs, Victor Berger, Ella Reeve Bloor, Emil Seidel, Daniel De Leon, Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, William Z. Foster, Abraham Cahan, Sidney Hillman, Morris Hillquit, Walter Reuther, Bill Haywood, Margaret Sanger, Florence Kelley, Rose Pastor Stokes, Mary White Ovington, Helen Keller, Inez Milholland, Floyd Dell, William Du Bois, Hubert Harrison, Upton Sinclair, Agnes Smedley, Victor Berger, Robert Hunter, George Herron, Kate Richards O'Hare, Helen Keller, Claude McKay, Sinclair Lewis, Daniel Hoan, Frank Zeidler, Max Eastman, Bayard Rustin, James Larkin, William Walling and Jack London.

Debs was a regular contributor to Appeal to Reason, a journal edited byJulius Wayland and Fred Warren. Warren was a well-known figure on the left and managed to persuade some of America's leading progressives to contribute to the journal. This included Jack London, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Upton Sinclair, Kate Richards O'Hare, Scott Nearing, Joe Haaglund Hill, Ralph Chaplin, Stephen Crane and Helen Keller and Eugene Debs. By 1902 its circulation reached 150,000, making it the fourth highest of any weekly in the United States.

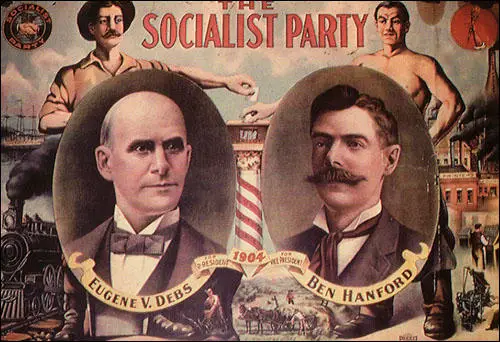

In the 1904 Presidential Election Eugene Debs was the Socialist Party of America candidate. His running-mate was Benjamin Hanford. Debs finished third to Theodore Roosevelt with 402,810 votes. This was an impressive performance and in the 1908 Presidential Election he managed to increase his vote to 420,793.

During this period Debs led the campaign for the release of William Haywood and Charles Moyer: "There have been twenty years of revolutionary education, agitation, and organization since the Haymarket tragedy, and if an attempt is made to repeat it, there will be a revolution and I will do all in my power to precipitate it. If they attempt to murder Moyer, Haywood, and their brothers, a million revolutionists at least will meet them with guns."

Between 1901 and 1912 membership of the Socialist Party of America grew from 13,000 to 118,000 and its journal Appeal to Reason was selling 500,000 copies a week. This provided a great platform for Debs and his running-mate, Emil Seidel, in the 1912 Presidential Election. During the campaign Debs explained why people should vote for him: "You must either vote for or against your own material interests as a wealth producer; there is no political purgatory in this nation of ours, despite the desperate efforts of so-called Progressive capitalists politicians to establish one. Socialism alone represents the material heaven of plenty for those who toil and the Socialist Party alone offers the political means for attaining that heaven of economic plenty which the toil of the workers of the world provides in unceasing and measureless flow. Capitalism represents the material hell of want and pinching poverty of degradation and prostitution for those who toil and in which you now exist, and each and every political party, other than the Socialist Party, stands for the perpetuation of the economic hell of capitalism. For the first time in all history you who toil possess the power to peacefully better your own condition. The little slip of paper which you hold in your hand on election day is more potent than all the armies of all the kings of earth."

Debs and Seidel won 901,551 votes (6.0%). This was the most impressive showing of any socialist candidate in the history of the United States. In some states the vote was much higher: Oklahoma (16.6), Nevada (16.5), Montana (13.6), Washington (12.9), California (12.2) and Idaho (11.5).

Debs had developed a very strong following in America. The journalist, Max Eastman, wrote: "Debs was a poet, and more gifted of poetry in private speech than in public oratory. He was the sweetest strong man I ever saw. There is both fighting and love in American socialism, and Debs knew how to fight. But that was not his genius. His genius was for love, the ancient real love, the miracle love that really identifies itself with the needs and wishes of others. That gave him more power than was possessed by many who were better versed in the subtleties of politics and oratory."

Debs and the Socialist Party were strong opponents of the First World War. He argued that the conflict had been caused by the imperialist competitive system. In an article in September 1915 he wrote: "I am not opposed to all war, nor am I opposed to fighting under all circumstances, and any declaration to the contrary would disqualify me as a revolutionist. When I say I am opposed to war I mean ruling class war, for the ruling class is the only class that makes war. It matters not to me whether this war be offensive or defensive, or what other lying excuse may be invented for it, I am opposed to it, and I would be shot for treason before I would enter such a war."

Between 1914 and 1917 Debs made several speeches explaining why he believed the United States should not join the war. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, several party members were arrested for violating the Espionage Act. After making a speech in Canton, Ohio, on 16th June, 1918, criticizing the legislation, Debs was arrested and sentenced to ten years in Atlanta Penitentiary.

The journalist, Heywood Broun, later commented: "I imagine that now it would be difficult to find many to defend the jailing of Debs. But at the time of the trial he received little support outside the radical ranks. The problem involved was not simple. I hated the thing they did to Debs even at the time, and I was not then a pacifist... Free speech is about as good a cause as the world has ever known. But, like the poor, it is always with us and gets shoved aside in favor of things which seem at some given moment more vital. They never are more vital. Not when you look back at them from a distance. When the necessity of free speech is most important we shut it off. Everybody favors free speech in the slack moments when no axes are being ground."

Debs was still in prison when he was the Socialist Party candidate in the 1920 Presidential Election. His program included proposals for improved labour conditions, housing and welfare legislation and an increase in the number of people who could vote in elections. With his running-mate, Seymour Stedman, they received 919,799 votes.

Lincoln Steffens was one of his visitors: "Debs was a happy man in prison. He loved everybody there, and everybody loved him - warden, guards, and convicts. Debs wanted to hear all about the Russian Revolution, the outrages of which he had denounced. It was not socialist, he pleaded, just as Emma Goldman declared it was not an anarchist revolution. Like so many reds who rejected Bolshevism, Debs the socialist could not abide the violence, bloodshed and tyranny."

Steffens was one of those people who campaigned for Debs to be released. In 1921 he had a meeting with Warren G. Harding: "After he had been in office awhile I went to him with a similar proposition, and to be sure of my ground, I sounded first a small number of governors to see if they would join in a general act of clemency for war and labor prisoners. Right away I got the reaction familiar to me: the politician governors would pardon their prisoners if the president would pardon his; the better men, the good, business governors, were most unwilling."

President Warren G. Harding pardoned Debs in December, 1921. Critical of the dictatorial policies of the Soviet Union, Debs refused to ally himself with the American Communist Party. Scott Molloy has pointed out: "Debs was in his twilight years now and the promise of social victory so alive a generation earlier had given way to despondency and defeat."

Eugene Victor Debs died in Elmhurst on 20th October, 1926. Heywood Broun wrote in the New York World: "Eugene Debs was a beloved figure and a tragic one. All his life he led lost causes. He captured the intense loyalty of a small section of our people, but I think that he affected the general thought of his time to a slight degree. Very few recognized him for what he was. It became the habit to speak of him as a man molded after the manner of Lenin or Trotsky. And that was a grotesque misconception... Though not a Christian by any precise standard, Debs was the Christian-Socialist type. That, I'm afraid, is outmoded. He did feel that wrongs could be righted by touching the compassion of the world. Perhaps they can. It has not happened yet.... The Debs idea will not die. To be sure, it was not his first at all. He carried on an older tradition. It will come to pass. There can be a brotherhood of man."

Primary Sources

(1) Eugene Debs, Appeal to Reason (29th December, 1900)

The machine became more perfect day by day; is lowered the wage of the worker, and in due course of time it became so perfect that it could be operated by unskilled labor of the woman, and she became a factor in industry. The owners of these machines were in competition with each other for trade in the market; it was war; cheaper and cheaper production was demanded, and cheaper labor was demanded.

In the march of time it became necessary to withdraw the children from school, and these machines came to be operated by the deft touch of the fingers of the child. In the first stage, machine was in competition with man; in the next, man in competition with both, and in the next, the child in competition with the whole combination.

Today there is more than three million women engaged in industrial pursuits in the United States, and more than two million children. It is not a question of white labor or black labor, or male labor or female or child labor, in this system; it is solely a question of cheap labor, without reference to the effect upon mankind.

(2) John Swinton, a journalist with the New York Times, saw Eugene Debs make a speech in 1894. He later wrote that Debs reminded him of Abraham Lincoln.

It seemed to me that both men were imbued with the same spirit. Both seemed to me as men of judgment, reason, earnestness and power. Both seemed to me as men of free, high, genuine and generous manhood. I took to Lincoln in my early life, as I took to Debs a third of a century later.

(3) Eugene Debs wrote about the arrest of William Haywood and Charles Moyer in Appeal to Reason (10th March, 1906)

There have been twenty years of revolutionary education, agitation, and organization since the Haymarket tragedy, and if an attempt is made to repeat it, there will be a revolution and I will do all in my power to precipitate it. If they attempt to murder Moyer, Haywood, and their brothers, a million revolutionists at least will meet them with guns.

(4) Eugene Debs, Appeal to Reason (23rd March, 1907)

Ferdinand Lassalle, the brilliant social revolutionist, once said that the war against capitalism was not a rose water affair. It is rather of the storm and tempest order. All kinds of attacks must be expected, and all kinds of wounds will be inflicted. You will be assailed within and without, spat upon by the very ones that you are doing your best to serve, and at certain crucial moments find yourself isolated, absolutely alone as if to compel surrender, but in those moments, if you have the nerve, you become supreme.

(5) Eugene Debs was the Socialist Party candidate for president in 1912. He wrote about his views in the article Why You Should Vote for Socialism (31st August, 1912)

You must either vote for or against your own material interests as a wealth producer; there is no political purgatory in this nation of ours, despite the desperate efforts of so-called Progressive capitalists politicians to establish one. socialism alone represents the material heaven of plenty for those who toil and the Socialist Party alone offers the political means for attaining that heaven of economic plenty which the toil of the workers of the world provides in unceasing and measureless flow.

Capitalism represents the material hell of want and pinching poverty of degradation and prostitution for those who toil and in which you now exist, and each and every political party, other than the Socialist Party, stands for the perpetuation of the economic hell of capitalism.

For the first time in all history you who toil possess the power to peacefully better your own condition. The little slip of paper which you hold in your hand on election day is more potent than all the armies of all the kings of earth.

(6) Eugene Debs, Appeal to Reason (11th September, 1915)

I am not opposed to all war, nor am I opposed to fighting under all circumstances, and any declaration to the contrary would disqualify me as a revolutionist. When I say I am opposed to war I mean ruling class war, for the ruling class is the only class that makes war. It matters not to me whether this war be offensive or defensive, or what other lying excuse may be invented for it, I am opposed to it, and I would be shot for treason before I would enter such a war.

Capitalists wars for capitalist conquest and capitalist plunder must be fought by the capitalists themselves so far as I am concerned, and upon that question there can be no compromise and no misunderstanding as to my position. I have no country to fight for; my country is the earth; I am a citizen of the world. I would not violate my principles for God, much less for a crazy kaiser, a savage czar, a degenerate king, or a gang of pot-bellied parasites.

I am opposed to every war but one; I am for the war with heart and soul, and that is the world-wide war of social revolution. In that war I am prepared to fight in any way the ruling class may make necessary, even to the barricades.

There is where I stand and where I believe the Socialist Party stands, or ought to stand, on the question of war.

(7) Eugene Debs, speech in Canton, Ohio (16th June 1918)

The other day they sentenced Kate Richards O'Hare to the penitentiary for five years. Think of sentencing a woman to the penitentiary simply for talking. The United States, under plutocratic rule, is the only country that would send a woman to prison for five years for exercising the right of free speech. If this be treason, let them make the most of it.

Let me review a bit of history in connection with this case. I have known Kate Richards O'Hare intimately for twenty years. I am familiar with her public record. Personally I know her as if she were my own sister. All who know Mrs. O'Hare know her to be a woman of unquestioned integrity. And they also know that she is a woman of unimpeachable loyalty to the Socialist movement. When she went out into North Dakota to make her speech, followed by plain-clothes men in the service of the government intent upon effecting her arrest and securing her prosecution and conviction - when she went out there, it was with the full knowledge on her part that sooner or later these detectives would accomplish their purpose. She made her speech, and that speech was deliberately misrepresented for the purpose of securing her conviction. The only testimony against her was that of a hired witness. And when the farmers, the men and women who were in the audience she addressed - when they went to Bismarck where the trial was held to testify in her favor, to swear that she had not used the language she was charged with having used, the judge refused to allow them to go upon the stand. This would seem incredible to me if I had not had some experience of my own with federal courts.

Rose Pastor Stokes! And when I mention her name I take off my hat. Here we have another heroic and inspiring comrade. She had her millions of dollars at command. Did her wealth restrain her an instant? On the contrary her supreme devotion to the cause outweighed all considerations of a financial or social nature. She went out boldly to plead the cause of the working class and they rewarded her high courage with a ten years' sentence to the penitentiary. Think of it! Ten years! What atrocious crime had she committed? What frightful things had she said? Let me answer candidly. She said nothing more than I have said here this afternoon. I want to admit - I want to admit without reservation that if Rose Pastor Stokes is guilty of crime, so am I. If she is guilty for the brave part she has taken in this testing time of human souls I would not be cowardly enough to plead my innocence. And if she ought to be sent to the penitentiary for ten years, so ought I without a doubt.

What did Rose Pastor Stokes say? Why, she said that a government could not at the same time serve both the profiteers and the victims of the profiteers. Is it not true? Certainly it is and no one can successfully dispute it. Roosevelt said a thousand times more in the very same paper, the Kansas City Star. Roosevelt said vauntingly the other day that he would be heard even if he went to jail. He knows very well that he is taking no risk of going to jail. He is shrewdly laying his wires for the Republican nomination in 1920 and he is an adept in making the appeal of the demagogue.

Rose Pastor Stokes never uttered a word she did not have a legal, constitutional right to utter. But her message to the people, the message that stirred their thoughts and opened their eyes - that must be suppressed; her voice must be silenced. And so she was promptly subjected to a mock trial and sentenced to the penitentiary for ten years. Her conviction was a foregone conclusion. The trial of a Socialist in a capitalist court is at best a farcical affair. What ghost of a chance had she in a court with a packed jury and a corporation tool on the bench? Not the least in the world. And so she goes to the penitentiary for ten years if they carry out their brutal and disgraceful graceful program. For my part I do not think they will. In fact I feel sure they will not. If the war were over tomorrow the prison doors would open to our people. They simply mean to silence the voice of protest during the war.

(8) In July, 1920, the journal, Appeal to Reason, reported on Kate Richards O'Hare visiting Eugene Debs in prison.

In a visit full of dramatic incidents, Kate Richards O'Hare visited Eugene V. Debs in the Federal penitentiary in Atlanta on 2nd July, to carry to him the love of Socialists everywhere.

Kate O'Hare was ushered into the prison; the two comrades met and embraced; Kate Richards O'Hare recently freed from the Federal prison and Eugene V. Debs in prison garb with nine years of prison life before him, with both his hands still upon her shoulders, said, "How happy I am to see you free, Kate."

"Your coming here is like a new sunlight to me. Tell me about your prison experiences," said Debs. She answered, "Gene, I am not thinking of myself, but of little Mollie Steimer who now occupies my cell at Jefferson City and of her appalling sentence of fifteen years. She is a nineteen-year-old little girl, smaller in stature than my Kathleen, whose sole crime is her love for the oppressed.

Then Kate opened her leather card-case and showed Debs her family group picture which she had carried with her during the fourteen months of prison life. The sight of that picture had afforded her much consolation through the hours of dreaded prison silence and monotony.

(9) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1965)

Debs was a poet, and more gifted of poetry in private speech than in public oratory. He was the sweetest strong man I ever saw. There is both fighting and love in American socialism, and Debs knew how to fight. But that was not his genius. His genius was for love, the ancient real love, the miracle love that really identifies itself with the needs and wishes of others. That gave him more power than was possessed by many who were better versed in the subtleties of politics and oratory.

(10) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

President Wilson received and read on his boat our amnesty memorandum, but he rejected the idea of it sharply, totally. He was in a fighting, acting mood, bitter and executive. And the American people were not ready for anything like peace. It looked better when Harding was president. After he had been in office awhile I went to him with a similar proposition, and to be sure of my ground, I sounded first a small number of governors to see if they would join in a general act of clemency for war and labor prisoners. Right away I got the reaction familiar to me: the politician governors would pardon their prisoners if the president would pardon his; the better men, the good, business governors, were most unwilling. Well, Harding was a politician; rumor had it that he was a sinner.

President Harding heard me out, his handsome face expressing his willingness and his doubt. He nodded, smiled, wagged his head. "Make peace at home," I said. "We've got it abroad. Let all the prisoners go who are in jail for fighting for labor, for peace, for-anything. Let 'em all out, with a proclamation, you and the governors."

"That's all right," he said, "for fellows like you and me, but they won't let me do it." He had the case of Eugene V. Debs, the socialist leader, before him; we all knew that, and I had asked his permission to visit Debs in Atlanta.

"I am going to pardon Debs," he said. "I have put that over, but a general amnesty?" He shook his head; then he perked up. "I'll tell you what I'll do," he said. "I'll make you a fair, sporting proposition. You get my cabinet and I'll do it. No. You get Hoover and my secretary of labor, and I'll get the rest myself, and we'll do it." And when I rushed out, quick, and came back, quick, with the most emphatic refusals of Hoover and the secretary of labor, Harding laughed. He did not say what he found so funny, but his laughter was so loud and sardonic that a secretary ran in and ran out.

The president had in his hand a typewritten paper which he pushed at me. "Here, look at this." It was a declaration his attorney general had dictated for Debs to sign when pardoned, a dirt-eating promise. "What would you do about that?" Harding asked, and when I looked up from reading it and said, with some feeling, that I would not pardon any man who would subscribe to such a statement, he nodded.

"I thought so," he muttered, and he crumpled the paper and dropped it. He pardoned Debs without any humiliating conditions.

When I visited Debs at Atlanta and told him what was coming, he was not elated. He was a happy man in prison. He loved everybody there, and everybody loved him - warden, guards, and convicts. Debs wanted to hear "all about the Russian Revolution," the outrages of which he had denounced. It was not socialist, he pleaded, just as Emma Goldman declared it was not an anarchist revolution. Like so many reds who rejected Bolshevism, Debs the socialist could not abide the violence, bloodshed, tyranny. They all had had their mental pictures of the heaven on earth that was coming, and this was not what they expected.

As I told Emma Goldman once, to her indignation, she was a Methodist sent to a Presbyterian heaven, and naturally she thought it was hell. I was asking Debs to wait and hear more about it, even to go to Russia and see it for himself, before judging the Soviet Republic. He described the horrors he had heard of, and he could describe; Debs had eloquence, but when he finished his fiery speech to me on the rude, wild ruthlessness of the Russians, I said very quietly: "True, 'Eugene. That's all true that you say. A revolution is no gentleman."

He sprang to his feet. "Of course," he exclaimed. "I forgot." And he promised me then and there never again to denounce the Russian Revolution on any charge without first hearing my answer to it. He did. When he got out he made a speech denouncing, as the socialist leader, the revolution and all its works, and he did not answer a letter of protest I addressed to him. I offered to go to Indianapolis to see him. I never saw Debs again, but he was never again very well.

(11) Heywood Broun, New York World (23rd October, 1926)

Eugene V. Debs is dead and everybody says that he was a good man. He was no better and no worse when he served a sentence at Atlanta.

I imagine that now it would be difficult to find many to defend the jailing of Debs. But at the time of the trial he received little support outside the radical ranks.

The problem involved was not simple. I hated the thing they did to Debs even at the time, and I was not then a pacifist. Yet I realize that almost nobody means precisely what he says when he makes the declaration, "I'm in favor of free speech." I think I mean it, but it is not difficult for me to imagine situations in which I would be gravely tempted to enforce silence on anyone who seemed to be dangerous to the cause I favored.

Free speech is about as good a cause as the world has ever known. But, like the poor, it is always with us and gets shoved aside in favor of things which seem at some given moment more vital. They never are more vital. Not when you look back at them from a distance. When the necessity of free speech is most important we shut it off. Everybody favors free speech in the slack moments when no axes are being ground.

It would have been better for America to have lost the war than to lose free speech. I think so, but I imagine it is a minority opinion. However, a majority right now can be drummed up to support the contention that it was wrong to put Debs in prison. That won't keep the country from sending some other Debs to jail in some other day when panic psychology prevails.

You see, there was another aspect to the Debs case, a point of view which really begs the question. It was foolish to send him to jail. His opposition to the war was not effective. A wise dictator, someone like Shaw's Julius Caesar, for instance, would have given Debs better treatment than he got from our democracy.

Eugene Debs was a beloved figure and a tragic one. All his life he led lost causes. He captured the intense loyalty of a small section of our people, but I think that he affected the general thought of his time to a slight degree. Very few recognized him for what he was. It became the habit to speak of him as a man molded after the manner of Lenin or Trotsky. And that was a grotesque misconception. People were constantly overlooking the fact that Debs was a Hoosier, a native product in every strand of him. He was a sort of Whitcomb Riley turned politically minded.

It does not seem to me that he was a great man. At least he was not a great intellect. But Woodward has argued persuasively that neither was George Washington. In summing up the Father of His Country, this most recent biographer says in effect that all Washington had was character. By any test such as that Debs was great. Certainly he had character. There was more of goodness in him than bubbled up in any other American of his day. He had some humor, or otherwise a religion might have been built up about him, for he was thoroughly Messianic. And it was a strange quirk which set this gentle, sentimental Middle-Westerner in the leadership of a party often fierce and militant.

Though not a Christian by any precise standard, Debs was the Christian-Socialist type. That, I'm afraid, is outmoded. He did feel that wrongs could be righted by touching the compassion of the world. Perhaps they can. It has not happened yet. Of cold, logical Marxism, Debs possessed very little. He was never the brains of his party. I never met him, but I read many of his speeches, and most of them seemed to be second-rate utterances. But when his great moment came a miracle occurred. Debs made a speech to the judge and jury at Columbus after his conviction, and to me it seems one of the most beautiful and moving passages in the English language. He was for that one afternoon touched with inspiration. If anybody told me that tongues of fire danced upon his shoulders as he spoke, I would believe it....

Something was in Debs, seemingly, that did not come out unless you saw him. I'm told that even those speeches of his which seemed to any reader indifferent stuff, took on vitality from his presence. A hard-bitten Socialist told me once, "Gene Debs is the only one who can get away with the sentimental flummery that's been tied onto Socialism in this country. Pretty nearly always it gives me a swift pain to go around to meetings and have people call me "comrade." That's a lot of bunk. But the funny part of it is that when Debs says "comrade" it's all right. He means it. That old man with the burning eyes actually believes that there can be such a thing as the brotherhood of man. And that's not the funniest part of it. As long as he's around I believe it myself."

With the death of Debs, American Socialism is almost sure to grow more scientific, more bitter, possibly more effective. The party is not likely to forget that in Russia it was force which won the day, and not persuasion.

I've said that it did not seem to me that Debs was a great man in life, but he will come to greatness by and by. There are in him the seeds of symbolism. He was a sentimental Socialist, and that line has dwindled all over the world. Radicals talk now in terms of men and guns and power, and unless you get in at the beginning of the meeting and orient yourself, this could just as well be Security Leaguers or any other junkers in session.

The Debs idea will not die. To be sure, it was not his first at all. He carried on an older tradition. It will come to pass. There can be a brotherhood of man.