Helen Keller

Helen Keller was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama on 27th June, 1880. Her father, Arthur H. Keller, was the editor for the North Alabamian, and had fought in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. At 19 months she suffered "an acute congestion of the stomach and brain (probably scarlet fever) which left her deaf and blind.

She later wrote in The Story of My Life: "In the dreary month of February, came the illness which closed my eyes and ears and plunged me into the unconsciousness of a new born baby. They called it acute congestion of the stomach and brain. The doctor thought I could not live. Early one morning, however, the fever left me as suddenly and mysteriously as it had come. There was great rejoicing in the family that morning, but no one not even the doctor, knew that I should never see or hear again." As a child she was taken to see Alexander G. Bell. He suggested that the family should contact the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston.

In 1886 the Perkins Institute provided Keller with the teacher Anne Sullivan. She later recalled: "We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten - a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away." The 21 year old Sullivan worked out an alphabet by which she spelled out words on Helen's hand. Gradually Keller was able to connect words with objects.

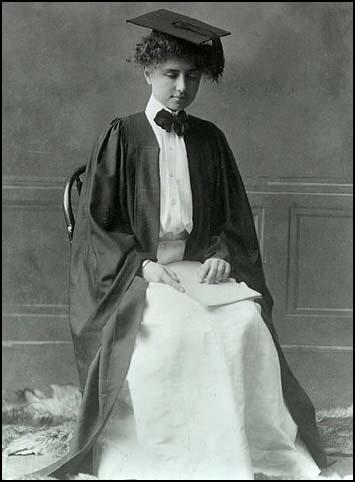

Sullivan's teaching skills and Keller's abilities, enabled her at the age of 16 to pass the admissions examinations for Radcliffe College. While at college she wrote the first volume of her autobiography, The Story of My Life. It was published serially in the Ladies' Home Journal and, in 1902, as a book. By the time she had graduated in 1904 she had mastered five languages.

While at college she developed a strong interest in women's rights and became a militant campaigner in favour of universal suffrage. She also became friends with several notable public figures including John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes and William Dean Howells. The journalist, Max Eastman, became a friend during this period. He later recalled: "The gleam of true, courageous and unaffected joy in living that shone out of her gray-blue eyes. Her face was round; she was a round-limbed girl, perpetually young in her bearing, as though her limitations had made it easy instead of hard to grow older."

Keller's political views were influenced by conversations she had with John Macy (Anne Sullivan's husband) and reading New Worlds for Old by H. G. Wells. In 1909 Keller became a socialist and was active in various campaigns including those in favour of birth control, trade unionism and against child labour and capital punishment.

Keller was a supporter of Emmeline Pankhurst and the militant Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. She told the New York Times: "I believe the women of England are doing right. Mrs Pankhurst is a great leader. The women of America should follow her example. They would get the ballot much faster if they did. They cannot hope to get anything unless they are willing to fight and suffer for it.

In 1912 Keller was interviewed by Ernest Gruening, a young journalist working for the Boston American. He later wrote about it in his autobiography, Many Battles (1973): "She had never before been interviewed for publication, so I communicated with her teacher-companion, Anne Sullivan Macy, and on securing assent went to their home in Wrentham... Helen Keller who, besides being deaf since infancy, was also blind. Miss Keller's voice was high-pitched with a peculiar metallic ring, but her speech was remarkably clear.... Miss Keller came out of the porch to greet me and, asking me to sit beside her, told me to put the fore and middle fingers on her right hand on my lips. By that means she could understand everything I said. She spoke with enthusiasm of her aspirations to help others who were deaf and blind, and revealed that she was a socialist, repeatedly referring to socialism as the cure for the nation's ills."

Keller joined the Socialist Party of America and campaigned for Eugene Debs and his running-mate, Emil Seidel, in the 1912 Presidential Election. During the campaign Debs explained why people should vote for him: "You must either vote for or against your own material interests as a wealth producer; there is no political purgatory in this nation of ours, despite the desperate efforts of so-called Progressive capitalists politicians to establish one. Socialism alone represents the material heaven of plenty for those who toil and the Socialist Party alone offers the political means for attaining that heaven of economic plenty which the toil of the workers of the world provides in unceasing and measureless flow. Capitalism represents the material hell of want and pinching poverty of degradation and prostitution for those who toil and in which you now exist, and each and every political party, other than the Socialist Party, stands for the perpetuation of the economic hell of capitalism." Debs and Seidel won 901,551 votes (6.0%). This was the most impressive showing of any socialist candidate in the history of the United States.

A book on Keller's socialist views, Out of the Dark, was published in 1913. She later wrote "I had once believed that we are all masters of our fate - that we could mould our lives into any form we pleased. I had overcome deafness and blindness sufficiently to be happy, and I supposed that anyone could come out victorious if he threw himself valiantly into life's struggle. But as I went more and more about the country I learned that I had spoken with assurance on a subject I knew little about. I forgot that I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment. Now, however, I learned that the power to rise in the world is not within the reach of everyone." Hattie Schlossberg wrote in the New York Call: "Helen Keller is our comrade, and her socialism is a living vital thing for her. All her speeches are permeated with the spirit of socialism."

In 1912 Keller joined the theIndustrial Workers of the World (IWW). A socialist trade union group that opposed the policies of American Federation of Labour. Keller wrote later: "Surely the demands of the IWW are just. It is right that the creators of wealth should own what they create. When shall we learn that we are related one to the other; that we are members of one body; that injury to one is injury to all? Until the spirit of love for our fellow-workers, regardless of race, color, creed or sex, shall fill the world, until the great mass of the people shall be filled with a sense of responsibility for each other’s welfare, social justice cannot be attained, and there can never be lasting peace upon earth."

Keller also wrote articles for the socialist journal, The Masses. Keller, a pacifist, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the journal came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp and articles by Max Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable."

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

TheIndustrial Workers of the World also came under pressure for its opposition to the First World War. In 1914, one of the leaders of the IWW, Joe Haaglund Hill was accused of the murder of a Salt Lake City businessman. Convicted on circumstantial evidence and despite of mass protests, Hill was shot by a firing squad on 19th November, 1915. Whereas another IWW leader, Frank Little, was lynched in Butte, Montana. Another leader of the IWW, William Haywood, was arrested under the Espionage Act.

In an article published in The Liberator, Keller argued: "During the last few months, in Washington State, at Pasco and throughout the Yakima Valley, many IWW members have been arrested without warrants, thrown into bull-pens without access to attorney, denied bail and trial by jury, and some of them shot. Did any of the leading newspapers denounce these acts as unlawful, cruel, undemocratic? No. On the contrary, most of them indirectly praised the perpetrators of these crimes for their patriotic service! On August 1st, of 1917, in Butte, Montana, a cripple, Frank Little, a member of the Executive Board of the IWW, was forced out of bed at three o’clock in the morning by masked citizens, dragged behind an automobile and hanged on a railroad trestle. Were the offenders punished? No. A high government official has publicly condoned this murder, thereby upholding lynch-law and mob rule."

Newspapers that had previously praised Keller's courage and intelligence now drew attentions to her disabilities. The editor of the Brooklyn Eagle wrote that her "mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development." Keller was furious and wrote a letter of complaint to the newspaper. "At that time the compliments he paid me were so generous that I blush to remember them. But now that I have come out for socialism he reminds me and the public that I am blind and deaf and especially liable to error.... Socially blind and deaf, it defends an intolerable system, a system that is the cause of much of the physical blindness and deafness which we are trying to prevent."

In 1919 Keller appeared in an autobiographical film, Deliverance, in an attempt to spread "a message of courage, a message of a brighter, happier future for all men". Keller as a young girl was played by Etna Ross and as a young woman by Ann Mason. According to one critic: "In the final and most inspirational sequence, we see the real Helen Keller working tirelessly as a public figure to improve conditions for other blind people, and helping them to learn useful trades."

When Helen Keller decided after 1921 that her main work was to be devoted to raising funds for the American Foundation of the Blind, her activities for the socialist movement diminished but did not cease. Philip S. Foner has argued: "No matter what social cause she espoused, Keller was always on the radical side of the movement." As a left-wing socialist she disliked "parlor socialists" who quickly abandoned the struggle when the situation became difficult and later became "hopelessly reactionary."

In 1929 she published her book Mainstream. It included the following: "I had once believed that we are all masters of our fate - that we could mould our lives into any form we pleased ... I had overcome deafness and blindness sufficiently to be happy, and I supposed that anyone could come out victorious if he threw himself valiantly into life's struggle. But as I went more and more about the country I learned that I had spoken with assurance on a subject I knew little about. I forgot that I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment ... Now, however, I learned that the power to rise in the world is not within the reach of everyone."

Keller's childhood education was depicted in The Miracle Worker, a play by William Gibson, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1960. An Oscar-winning feature film in 1962, starring Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke, appeared two years later.

Helen Keller died in Westport, Connecticut, on 1st June, 1968.

Primary Sources

(1) Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (1902)

In the dreary month of February, came the illness which closed my eyes and ears and plunged me into the unconsciousness of a new born baby. They called it acute congestion of the stomach and brain. The doctor thought I could not live. Early one morning, however, the fever left me as suddenly and mysteriously as it had come. There was great rejoicing in the family that morning, but no one not even the doctor, knew that I should never see or hear again.

I fancy I still have confused recollections of that illness. I especially remember the tenderness with which my mother tried to soothe me in my waking hours of fret and pain, and the agony and bewilderment with which I awoke after a tossing half sleep, and turned my eyes, so dry and hot, to the wall, away from the once-loved light, which came to me dim and yet more dim each day. But, except for these fleeting memories, if, indeed, they be memories, it all seems very unreal

like a nightmare. Gradually I got used to the silence and darkness that surrounded me and forgot that it had ever been different, until she came - my teacher - who was to set my spirit free. But during the first nineteen months of my life I had caught glimpses of broad, green fields, a luminous sky, trees and flowers which the darkness that followed could not wholly blot out. If we have once seen, "the day is ours, and what the day has shown."

(2) In her autobiography, The Story of My Life, Helen Keller explained how Anne Sullivan taught her how to read.

We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten - a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away.

I left the well-house eager to learn. Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a new thought. As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life. That was because I saw everything with the strange, new sight that had come to me. On entering the door I remembered the doll I had broken. I felt my way to the hearth and picked up the pieces. I tried vainly to put them together. Then my eyes filled with tears; for I realized what I had done, and for the first time I felt repentance and sorrow.

I learned a great many new words that day. I do not remember what they all were; but I do know that mother, father, sister, teacher were among them - words that were to make the world blossom for me, "like Aaron's rod, with flowers." It would have been difficult to find a happier child than r was as I lay in my crib at the close of that eventful day and lived over the joys it had brought me, and for the first time longed for a new day to come.

(3) Helen Keller, Optimism (1903)

Could we choose our environment, and were desire in human undertakings synonymous with endowment, all men would, I suppose, be optimists. Certainly most of us regard happiness as the proper end of all earthly enterprise. The will to be happy animates alike the philosopher, the prince and the chimney-sweep. No matter how dull, or how mean, or how wise a man is, he feels that happiness is his indisputable right.

It is curious to observe what different ideals of happiness people cherish, and in what singular places they look for this well-spring of their life. Many look for it in the hoarding of riches, some in the pride of power, and others in the achievements if art and literature; a few seek it in the exploration of their own minds, or in search for knowledge.

Most people measure their happiness in terms of physical pleasure and material possession. Could they win some visible goal which they have set on the horizon, how happy they could be! Lacking this gift or that circumstance, they would be miserable. If happiness is to be so measured, I who cannot hear or see have every reason to sit in a corner with folded hands and weep. If I am happy in spite of my deprivations, if my happiness is so deep that it is a faith, so thoughtful that it becomes a philosophy of life, - if, in short, I am an optimist, my testimony to the creed of optimism is worth hearing. As sinners stand up in meeting and testify to the goodness of God, so one who is called afflicted may rise up in gladness of conviction and testify to the goodness of life.

Once I knew the depth where no hope was, and darkness lay on the face of all things. Then love came and set my soul free. Once I knew only darkness and stillness. Now I know hope and joy. Once I fretted and beat myself against the wall that shut me in. Now I rejoice in the consciousness that I can think, act and attain heaven. My life was without past or future; death, the pessimist would say, "a consummation devoutly to be wished." But a little word from the fingers of another fell into my hand that clutched at emptiness, and my heart leaped to the rapture of living. Night fled before the day of thought, and love and joy and hope came up in a passion of obedience to knowledge. Can anyone who escaped such captivity, who has felt the thrill and glory of freedom, be a pessimist?

My early experience was thus a leap from bad to good. If I tried, I could not check the momentum of my first leap out of the dark; to move breast forward as a habit learned suddenly at that first moment of release and rush into the light. With the first word I used intelligently, I learned to live, to think, to hope. Darkness cannot shut me in again. I have had a glimpse of the shore, and can now live by the hope of reaching it.

So my optimism is no mild and unreasoning satisfaction. A poet once said I must be happy because I did not see the bare, cold present, but lived in a beautiful dream. I do live in a beautiful dream; but that dream is the actual, the present, - not cold, but warm; not bare, but furnished with a thousand blessings. The very evil which the poet supposed would be a cruel disillusionment is necessary to the fullest knowledge of joy. Only by contact with evil could I have learned to feel by contrast the beauty of truth and love and goodness.

It is a mistake always to contemplate the good and ignore the evil, because by making people neglectful it lets in disaster. There is a dangerous optimism of ignorance and indifference. It is not enough to say that the twentieth century is the best age in the history of mankind, and to take refuge from the evils of the world in skyey (sic) dreams of good. How many good men, prosperous and contented, looked around and saw naught but good, while millions of their fellow-men were bartered and sold like cattle! No doubt, there were comfortable optimists who thought Wilberforce a meddlesome fanatic when he was working with might and main to free the slaves. I distrust the rash optimism in this country that cries, "Hurrah, we're all right! This is the greatest nation on earth," when there are grievances that call loudly for redress. That is false optimism. Optimism that does not count the cost is like a house builded (sic) on sand. A man must understand evil and be acquainted with sorrow before he can write himself an optimist and expect others to believe that he has reason for the faith that is in him.

I know what evil is. Once or twice I have wrestled with it, and for a time felt its chilling touch on my life; so I speak with knowledge when I say that evil is of no consequence, except as a sort of mental gymnastic. For the very reason that I have come in contact with it, I am more truly an optimist. I can say with conviction that the struggle which evil necessitates is one of the greatest blessings. It makes us strong, patient, helpful men and women. It lets us into the soul of things and teaches us that although the world is full of suffering, it is full also of the overcoming of it. My optimism, then, does not rest on the absence of evil, but on a glad belief in the preponderance of good and a willing effort always to cooperate with the good, that it may prevail. I try to increase the power God has given me to see the best in everything and every one, and make that Best a part of my life. The world is sown with good; but unless I turn my glad thoughts into practical living and till my own field, I cannot reap a kernel of the good.

Thus my optimism is grounded in two worlds, myself and what is about me. I demand that the world be good, and lo, it obeys. I proclaim the world good, and facts range themselves to prove my proclamation overwhelmingly true. To what good I open the doors of my being, and jealously shut them against what is bad. Such is the force of this beautiful and wilful conviction, it carries itself in the face of all opposition. I am never discouraged by absence of good. I never can be argued into hopelessness. Doubt and mistrust are the mere panic of timid imagination, which the steadfast heart will conquer, and the large mind transcend.

As my college days draw to a close, I find myself looking forward with beating heart and bright anticipations to what the future holds of activity for me. My share in the work of the world may be limited; but the fact that it is work makes it precious. Nay, the desire and will to work is optimism itself....

I, too, can work, and because I love to labor with my head and my hands, I am an optimist in spite of all. I used to think I should be thwarted in my desire to do something useful. But I have found out that through the ways in which I can make myself useful are few, yet the work open to me is endless. The gladdest laborer in the vineyard may be a cripple. Even should the others outstrip him, yet the vineyard ripens in the sun each year, and the full clusters weigh into his hand. Darwin could work only half an hour at a time; yet in many diligent half-hours he laid anew the foundations of philosophy. I long to accomplish a great and noble task; but it is my chief duty and joy to accomplish humble tasks as though they were great and noble. It is my service to think how I can best fulfil the demands that each day makes upon me, and to rejoice that others can do what I cannot. Green, the historian, tells us that the world is moved along, not only by the mighty shoves of its heroes, but also by the aggregate of the tiny pushes of each honest worker; and that thought alone suffices to guide me in this dark world and wide. I love the good that others do; for their activity is an assurance that whether I can help that whether I can help or not, the true and the good will stand sure.

(4) Max Eastman, wrote about Helen Keller in his book, Love and Revolution (1965)

The gleam of true, courageous and unaffected joy in living that shone out of her gray-blue eyes. Her face was round; she was a round-limbed girl, perpetually young in her bearing, as though her limitations had made it easy instead of hard to grow older.

(5) When Fred Warren was arrested and imprisoned for offering a reward for the arrest of William S. Taylor, the former governor of Kentucky, Helen Keller was one of those who campaigned for his release. She wrote about the case in the socialist journal, Appeal to Reason (24th December, 1910)

The more I study Mr. Warren's case in the light of the United States constitution, which I have under my fingers, the more I am persuaded either that I do not understand, or that the judges do not. To what twistings, turnings and dark interpretation must the judges of the circuit court be driven in order to send Mr. warren to prison! As I understand it, a federal law defining the kind of matter which it is a crime to mail has been stretched to cover his act. What was the act? The offer of a reward was printed on the outside of envelopes mailed from Girard by Mr. Warren. This was construed as threatening because it was an encouragement to others to kidnap a man under indictment.

Several years ago three officers of the Western Federation of Miners were indicted for a murder committed in Idaho. They were in Colorado, and the governor of that state did not extradite them. They were kidnapped and brought to an Idaho prison. They applied to the supreme court for a writ of habeas corpus, on the ground that they were illegally held because they had been illegally captured. The supreme court replied: "Even if it be true that the arrest and deportation of Pettibone, Moyer and Hayward from Colorado was by fraud and connivance to which the governor of Colorado was a party, this does not make out a case of violation of the rights of the appellants under the constitution and the laws of the United States."

One need not be a Socialist to realize the significance, the gravity, not of Mr. Warren's offense, but of the offense of the judges against the constitution, and against democratic rights. It is provided that "congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press." Surely this means that we are free to print and mail any innocent matter. What Mr. Warren printed and mailed had been established by the supreme court as innocent. What beam was in the eye of the honorable judges of the supreme court? Or what mote was in the eye of the justices of the circuit courts?

It has been my duty, my life-work to study physical blindness, its causes and its prevention. I learn that our physicians are making great progress in the cure and the prevention of blindness. What surgery of politics, what antiseptic of common sense and right thinking, shall be applied to cure the blindness of the people, who are the court of last resort?

(6) Helen Keller, letter to a friend in England (1911)

Our democracy is but a name. We vote? What does that mean? It means that we choose between two bodies of real, though not avowed, autocrats, We choose between Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

You ask for votes for women. What good can votes do when ten-elevenths of the land of Great Britain belongs to 200,000 and only one-eleventh to the rest of the 40,000,000? Have your men with their millions of votes freed themselves from this injustice?

(7) Helen Keller, introduction to a book of poems by Arturo Giovannitti entitled Arrows in the Gate (1914)

No one has ever given me a good reason why we should obey unjust laws. When a government depends for "law and order" upon the militia and the police, its mission in the world is nearly finished. We believe, at least we hope, that our capitalist government is near its end. We wish to hasten its end. I am sure this book will go on its way thrilling to new courage those who fight for freedom. It will move some to think and keep them glad that they have thought.

(8) Helen Keller, speech (19th December, 1915)

The burden of war always falls heaviest on the toilers. They are taught that their masters can do no wrong, and go out in vast numbers to be killed on the battlefield. And what is their reward? If they escape death they come back to face heavy taxation and have their burden of poverty doubled. Through all the ages they have been robbed of the just rewards of their patriotism as they have been of the just reward of their labor.

The only moral virtue of war is that it compels the capitalist system to look itself in the face and admit it is a fraud. It compels the present society to admit that it has no morals it will not sacrifice for gain. During a war, the sanctity of a home, and even of private property is destroyed. Governments do what it is said the "crazy Socialists" would do if in power.

In spite of the historical proof of the futility of war, the United States is preparing to raise a billion dollars and a million soldiers in preparation for war. Behind the active agitators for defense you will find J. P. Morgan & Co., and the capitalists who have invested their money in shrapnel plants, and others that turn out implements of murder. They want armaments because they beget war, for these capitalists want to develop new markets for their hideous traffic.

I look upon the whole world as my fatherland, and every war has to me a horror of a family feud. I look upon true patriotism as the brotherhood of man and the service of all to all. The only fighting that saves is the one that helps the world toward liberty, justice and an abundant life for all.

To prepare this nation in the true sense of the word, not for war, but for peace and happiness, the State should govern every department of industry, health and education in such a way as to maintain the bodies and minds of the people in soundness and efficiency. Then, the nation will be prepared to withstand the demand to fight for a perpetuation of its own slavery at the bidding of a tyrant.

After all, the best preparedness is one that disarms the hostility of other nations and makes friends of them. Nothing is to be gained by the workers from war. They suffer all the miseries, while the rulers reap the rewards. Their wages are not increased, nor their toil made lighter, nor their homes made more comfortable. The army they are supposed to raise can be used to break strikes as well as defend the people.

If the democratic measures of preparedness fall before the advance of a world empire, the worker has nothing to fear. No conqueror can beat down his wages more ruthlessly or oppress him more than his own fellow citizens of the capitalist world are doing. The worker has nothing to lose but his chains, and he has a world to win. He can win it at one stroke from a world empire. We must form a fully equipped, militant international union so that we can take possession of such a world empire.

(9) Helen Keller, The Liberator (1918)

Down through the long, weary years the will of the ruling class has been to suppress either the man or his message when they antagonized its interests. From the execution of the propagandist and the burning of books, down through the various degrees of censorship and expurgation to the highly civilized legal indictment and winking at mob crime by constituted authorities, the cry has ever been “crucify him!” The ideas and activities of minorities are misunderstood and misrepresented. It is easier to condemn than to investigate. It takes courage to steer one’s course through a storm of abuse and ignominy. But I believe that discussion of even the most bitterly controverted matters is demanded by our love of justice, by our sense of fairness and an honest desire to understand the problems that are rending society. Let us review the facts relating to the situation of the IWWs since the United States of America entered the war with the declared purpose to conserve the liberties of the free peoples of the world.

During the last few months, in Washington State, at Pasco and throughout the Yakima Valley, many “IWW” members have been arrested without warrants, thrown into “bull-pens” without access to attorney, denied bail and trial by jury, and some of them shot. Did any of the leading newspapers denounce these acts as unlawful, cruel, undemocratic? No. On the contrary, most of them indirectly praised the perpetrators of these crimes for their patriotic service!

On August 1st, of 1917, in Butte, Montana, a cripple, Frank Little, a member of the Executive Board of the IWW, was forced out of bed at three o’clock in the morning by masked citizens, dragged behind an automobile and hanged on a railroad trestle. Were the offenders punished? No. A high government official has publicly condoned this murder, thereby upholding lynch-law and mob rule.

On the 12th of last July [1917], 1200 miners were deported from Bisbee, Arizona, without legal process. Among them were many who were not IWWs or even in sympathy with them. They were all packed into freight cars like cattle and flung upon the desert of New Mexico, where they would have died of thirst and hunger if an outraged society had not protested. President Wilson telegraphed the Governor of Arizona that it was a bad thing to do, and a commission was sent to investigate. But nothing has been done. No measures have been taken to return the miners to their homes and families.

Last September the 5th, an army of officials raided every hall and office of the IWW from Maine to California. They rounded up 166 IWW officers, members and sympathizers, and now they are in jail in Chicago, awaiting trial on the general charge of conspiracy.

In a short time these men will be tried in a Chicago court. The newspapers will be full of stupid, if not malicious comments on their trial. Let us keep an open mind. Let us try to preserve the integrity of our judgment against the misrepresentation, ignorance and cowardice of the day. Let us refuse to yield to conventional lies and censure. Let us keep our hearts tender towards those who are struggling mightily against the greatest evils of the age. Who is truly indicted, they or the social system that has produced them? A society that permits the conditions out of which the IWWs have sprung, stands self-condemned.

The IWW is pitted against the whole profit-making system. It insists that there can be no compromise so long as the majority of the working class live in want, while the master class lives in luxury. According to its statement, “there can be no peace until the workers organize as a class, take possession of the resources of the earth and the machinery of production and distribution, and abolish the wage-system.” In other words, the workers in their collectivity must own and operate all the essential industrial institutions and secure to each laborer the full value of his produce. I think it is for this declaration of democratic purpose, and not for any wish to betray their country, that the IWW members are being persecuted, beaten, imprisoned and murdered.

Surely the demands of the IWW are just. It is right that the creators of wealth should own what they create. When shall we learn that we are related one to the other; that we are members of one body; that injury to one is injury to all? Until the spirit of love for our fellow-workers, regardless of race, color, creed or sex, shall fill the world, until the great mass of the people shall be filled with a sense of responsibility for each other’s welfare, social justice cannot be attained, and there can never be lasting peace upon earth.

I know those men are hungry for more life, more opportunity. They are tired of the hollow mockery of mere existence in a world of plenty. I am glad of every effort that the working men make to organize. I realize that all things will never be better until they are organized, until they stand all together like one man. That is my one hope of world democracy. Despite their errors, their blunders and the ignominy heaped upon them, I sympathize with the IWWs. Their cause is my cause. While they are threatened and imprisoned, I am manacled. If they are denied a living wage, I, too, am defrauded. While they are industrial slaves, I cannot be free. My hunger is not satisfied while they are unfed. I cannot enjoy the good things of life that come to me while they are hindered and neglected.

The mighty mass-movement of which they are a part is discernible all over the world. Under the fire of the great guns, the workers of all lands, becoming conscious of their class, are preparing to take possession of their own.

That long struggle in which they have successively won freedom of body from slavery and serfdom, freedom of mind from ecclesiastical despotism, and more recently a voice in government, has arrived at a new stage. The workers are still far from being in possession of themselves or their labor. They do not own and control the tools and materials which they must use in order to live, nor do they receive anything like the full value of what they produce. Workingmen everywhere are becoming aware that they are being exploited for the benefit of others, and that they cannot be truly free unless they own themselves and their labor. The achievement of such economic freedom stands in prospect - and at no distant date- as the revolutionary climax of the age.

(10) Helen Keller, Midstream (1929)

I had once believed that we are all masters of our fate - that we could mould our lives into any form we pleased ... I had overcome deafness and blindness sufficiently to be happy, and I supposed that anyone could come out victorious if he threw himself valiantly into life's struggle. But as I went more and more about the country I learned that I had spoken with assurance on a subject I knew little about. I forgot that I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment ... Now, however, I learned that the power to rise in the world is not within the reach of everyone.

(11) Helen Keller, Going Back to School (September, 1934)

Education should train the child to use his brains, to make for himself a place in the world and maintain his rights even when it seem that society would shove him into the scrap-heap.

Education is not to fit us to get ahead of our fellows and to dominate them. It is rather to develop our talents and personalities and stimulate us to use our faculties effectively.

If our sympathies and understanding are not educated, the fact that we have a college degree, or that we have discovered a new fact in science does not make us educated men and women. The only way to judge the value of education is by what it does.

To be influenced in our school years to love our fellowmen is not sentimentalism. It is quite as necessary to our well-being as fresh air and food to the body, and a feeling for fair play, generosity and consideration can be instilled into every normal child.

Many a child seems stupid because his parents and teachers are too impatient or too busy to care what he is really interested in. If educators tried to find out what the student especially wants to do, how much time would be saved that is now wasted in teaching things which will never mean anything to him!

This great republic is a mockery of freedom as long as you are doomed to dig and sweat to earn a miserable living while the masters enjoy the fruit of your toil. What have you to fight for? National independence? That means the masters' independence. The laws that send you to jail when you demand better living conditions? The flag? Does it wave over a country where you are free and have a home, or does it rather symbolize a country that meets you with clenched fists when you strike for better wages and shorter hours? Will you fight for your masters' religion which teaches you to obey them even when they tell you to kill one another?

Why don't you make a junk heap of your masters' religion, his civilization, his kings and his customs that tend to reduce a man to a brute and God to a monster? Let there go forth a clarion call for liberty. Let the workers form one great world-wide union, and let there be a globe-encircling revolt to gain for the workers true liberty and happiness.

(12) Alden Whitman, New York Times (2nd June, 1968)

In 1909 she (Helen Keller) joined the Socialist party in Massachusetts. For many years she was an active member, writing incisive articles in defense of Socialism, lecturing for the party, supporting trade unions and strikes and opposing American entry into World War I. She was among those Socialists who welcomed the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917.

Although Miss Keller's Socialist activities diminished after 1921, when she decided that her chief life work was to raise funds for the American Foundation for the Blind, she was always responsive to Socialist and Communist appeals for help in causes involving oppression or exploitation of labor. As late as 1957 she sent a warm greeting to Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the Communist leader, then in jail on charges of violating the Smith Act.