Child Labor

In the early days of the Industrial Revolution, factory owners in the United States employed child workers. In Britain, child labor became a major issue in the 19th century and eventually legislation was passed that brought it to an end.

In 1892 the social reformer, John Peter Altgeld, was elected as governor of Illinois. Soon afterwards he managed to persuade the state legislature to pass legislation controlling child labour. This included a law limiting women and children to a maximum eight-hour day. To enforce this legislation he appointed one of the country's leading campaigners against child labour, Florence Kelley, as the state's first chief factory inspector. She recruited a staff of twelve, five of whom were women, including Alzina Stevens as her chief assistant. However, this success was short-lived and in 1895 the Illinois Association of Manufacturers got the law repealed.

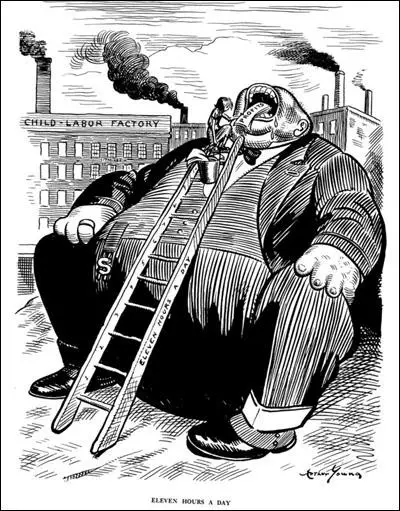

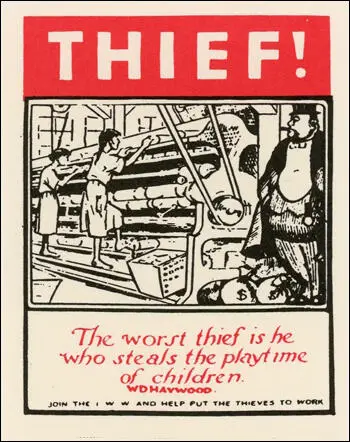

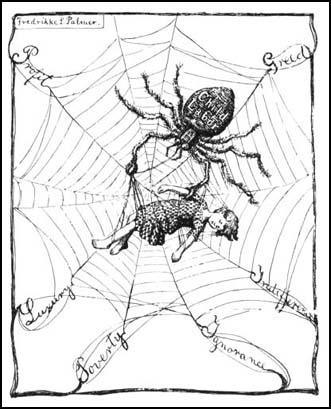

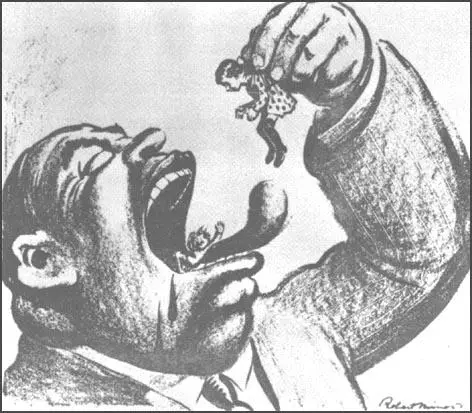

Julius Wayland and Fred Warren, the editors as the socialist journal, Appeal to Reason, were strong opponents of child labor and published a series of articles on the subject. This included the moving piece on the death of Roselie Randazzo by Kate Richards O'Hare and other articles by Eugene Debs and Mary 'Mother' Jones. Norman Hapgood of Collier's Weekly and other muckraking journalists also became heavily involved in this campaign. William Haywood, the leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was reported as saying: "The worst thief is he who steals the playtime of children."

The National Child Labour Committee was formed in 1904 in an attempt to persuade Congress to regulate child labour. One of its members, Jane Addams, reported in 1907 that there were over two million children under the age of sixteen in paid employment in the United States. She went on to argue that this helped to explain why there were "580,000 children between the ages of ten and fourteen years, who cannot read or write".

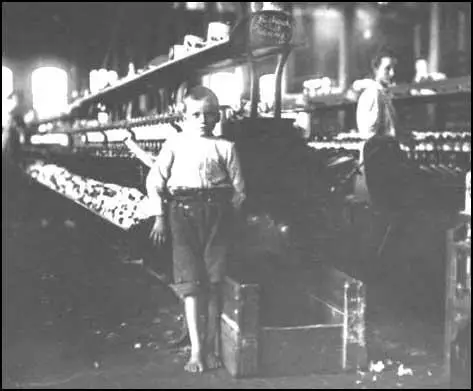

In 1908 the National Child Labor Committee employed Lewis Hine as their staff investigator and photographer. Hine travelled the country taking pictures of children working in factories. Hine also lectured on the subject and once told one audience: "Perhaps you are weary of child labour pictures. Well, so are the rest of us, but we propose to make you and the whole country so sick and tired of the whole business that when the time for action comes, child labour pictures will be records of the past."

At the beginning of the 19th century a group of social reformers involved in the Hull House settlement in Chicago, began to call for a federal agency to help protect children. People involved in this campaign included Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr, Robert Hunter, Henry Damerest Lloyd, Julia Lathrop, Lillian Wald, Alzina Stevens, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Florence Kelley, Mary McDowell, Alice Hamilton and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In 1912 President William Taft created the Children's Bureau to "investigate and report upon all matters pertaining to the welfare of children and child life among all classes of our people." Taft appointed Julia Lathrop, a member of the Hull House settlement, as the chief of the bureau. Over the next nine years Lathrop directed research into the dangers of child labour.

Alice Hamilton was one of those involved in this research and she provided evidence that industrial toxic substances, such as lead, nitrous fumes and viscose rayon, were causing serious side effects including mental illness, loss of vision, paralysis and sometimes death.

In 1916 Congress made its first effort to control child labour by passing the Keating-Owen Act. The legislation forbade the transportation among states of products of factories, shops or canneries employing children under 14 years of age, of mines employing children under 16 years of age, and the products of any of these employing children under 16 who worked at night or more than eight hours a day. In 1918 the Supreme Court ruled that the Keating-Owen Act was unconstitutional.

After the Supreme Court ruled that the Keating-Owen Act was unconstitutional, Congress passed a Second Child Labor Law. This levied a tax of ten per cent on the net profits of factories employing children under the age of 14, and of mines and quarries employing children under the age of 16. This legislation was declared unconstitutional as a result of the Drexel Furniture Company case in 1922.

Grace Abbott, who had replaced Julia Lathrop as head of the Children's Bureau in 1921, advocated that the only way this problem could be solved was by a change in the Constitution. In 1924 Congress passed an amendment to the Constitution giving itself the right to regulate child labour under 16 years of age. However, only 28 states ratified this Amendment.

in a textile factory in Tennessee, in 1910.

Frances Perkins, who had been recruited to the campaign against child labour after hearing a speech on the subject by Florence Kelley in 1902, was appointed as the Secretary of Labor in 1933 by the new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt. She therefore became the first woman in American history to hold a Cabinet post. Perkins immediately tried to persuade Roosevelt to bring an end to child labour. However, it was not until June, 1938, that Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act.

The main objective of the act was to eliminate "labor conditions detrimental to the maintenance of the minimum standards of living necessary for health, efficiency and well-being of workers". This included the prohibition of child labour in all industries engaged in producing goods in inter-state commerce. It set the minimum age at 14 for employment outside of school hours in non-manufacturing jobs, at 16 for employment during school hours, and 18 for hazardous occupations.

Primary Sources

(1) Eugene Debs, Appeal to Reason (29th December, 1900)

The machine became more perfect day by day; is lowered the wage of the worker, and in due course of time it became so perfect that it could be operated by unskilled labor of the woman, and she became a factor in industry. The owners of these machines were in competition with each other for trade in the market; it was war; cheaper and cheaper production was demanded, and cheaper labor was demanded.

In the march of time it became necessary to withdraw the children from school, and these machines came to be operated by the deft touch of the fingers of the child. In the first stage, machine was in competition with man; in the next, man in competition with both, and in the next, the child in competition with the whole combination.

Today there is more than three million women engaged in industrial pursuits in the United States, and more than two million children. It is not a question of white labor or black labor, or male labor or female or child labor, in this system; it is solely a question of cheap labor, without reference to the effect upon mankind.

(2) Robert Hunter, Poverty (1904)

On cold, rainy mornings, at the dusk of dawn, I have been awakened, two hours before my rising time, by the monotonous clatter of hobnailed boots on the plank sidewalks, as the procession to the factory passed under my window. Heavy, brooding men, tired, anxious women, thinly dressed, unkempt little girls, and frail, joyless little lads passed along, half awake, not one uttering a word as they hurried to the great factory. From all directions thousands were entering the various gates - children of every nation of Europe.

(3) Kate Richards O'Hare, wrote an article on child labour that was published in Appeal to Reason. The material on Roselie Randazzo, an Italian immigrant, was collected while she worked in an artificial flower factory in New York City (19th November, 1904)

Walking up the steps I came upon Roselie, the little Italian girl who sat next to me at the long work table. Roselie, whose fingers were the most deft in the shop and whose blue-black curls and velvety eyes I had almost envied as I often wondered why nature should have bestowed so much more than an equal share of beauty on the little Italian. Overtaking her I noticed she clung to the banister with one hand and held a crumpled mitten to the lips with the other. As we entered the cloak room she noticed my look of sympathy and weakly smiling said in broken English. "Oh, so cold! It hurta me here," and she laid her hand on her throat.

Seated at the long table the forelady brought a great box of the most exquisite red satin roses, and glancing sharply at Roselie said; "I hope you're not sick this morning; we must have these roses and you are the only one who can do them; have them ready by noon."

Soon a busy hum filled the room and in the hurry and excitement of my work I forgot Roselie until a shrill scream from the little Jewess across the table reached me and I turned in time to see Roselie fall forward among the flowers. As I lifted her up the hot blood spurted from her lips, staining my hands and spattering the flowers as it fell.

The blood-soaked roses were gathered up, the forelady grumbling because many were ruined, and soon the hum of industry went on as before. But I noticed that one of the great red roses had a splotch of red in its golden heart, a tiny drop of Rosie's heart's blood and the picture of the rose was burned in my brain.

The next morning I entered the grim, gray portals of Bellevue Hospital and asked for Roselie. "Roselie Randazzo," the clerk read from the great register. "Roselie Randazzo, seventeen; lives East Fourth street; taken from Marks' Artificial Flower Factory; hemorrhage; died 12.30 p.m." When I said that it was hard that she should die, so young and so beautiful, the clerk answered: "Yes, that's true, but this climate is hard on the Italians; and if the climate don't finish them the sweat shops or flower factories do," and then he turned to answer the questions of the woman who stood beside me and the life story of the little flower maker was finished.

(4) In October, 1908, Mary Mother Jones wrote about child labour in the socialist journal, Appeal to Reason . The article dealt with the factory owner, Braxton Comer, the Governor of Alabama who owned a large textile mill near Birmingham.

It had been thirteen years since I bid farewell to the workers in Alabama, and went forth to other fields to fight their battles. I returned in 1908 to see what they were doing for the welfare of their children. Governor Cromer, being the chief star of the state, I went to Abdale, on the outskirts of Birmingham, to take a glance at his slave pen. I found there somewhere between five and six hundred slaves. The governor, who in his generous nature could provide money for Jesus, reduced the wages of his slaves first 10 per cent and then 16.

As the wretches were already up against starvation, a few of them struck, and I went with an organizer and the editor of the editor of the Labor Advocate to help organize the slaves into a union of their craft. I addressed the body, and after I got through quite a large number became members of the Textile Workers Union.

When I was in Alabama thirteen years ago, they had no child labor law. Since then they passed a very lame one. They evade the law in this way: a child who has passed his or her twelfth year can take in his younger brothers or sisters from six years on, and got them to work with him. They are not on the pay roll, but the pay for these little ones goes into the elder one's pay. So that when you look at the pay roll you think this one child makes quite a good bit when perhaps there are two or three younger than he under the lash.

One woman told me that her mother had gone into that mill and worked, and took four children with her. She says, "I have been in the mill since I was four years old. I am now thirty-four." She looked to me as if she was sixty. She had a kindly nature if treated right, but her whole life and spirit was crushed out beneath the iron wheels of Comer's greed. When you think of the little ones that his mother brings forth you can see how society is cursed with an abnormal human being. She knew nothing but the whiz of a machinery in the factory.

The wives, mothers and the children all go in to produce dividends, profit, profit, profit. The brutal governor is a pillar of the First Methodist church in Birmingham. On Sunday he gets up and sings, "O Lord will you have another star for my crown when I get there?"

I saw the little ones lying on the bed shaking with chills and I could hear them ask parent and masters, what they were here for; what crime they had committed that they were brought here and sold to the dividend auctioneer.

The high temperature of the mills combined with an abnormal humidity of the air produced by steaming as done by manufacturers makes bad material weave easier and tends to diminish the workers' power of resisting disease. The humid atmosphere promotes perspiration, but makes evaporation from the skin more difficult; and in this condition the operator, when he leaves the mill, has to face a much reduced temperature which produces serious chest infections. They are all narrow-chested, thin, disheartened looking.

(5) The Manufacturers Record published an article against attempts to bring an end to child labor (4th September, 1924)

This proposed amendment is fathered by Socialists, Communists, and Bolshevists. They are the active workers in its favor. They look forward to its adoption as giving them the power to nationalize the children of the land and bring about in this country the exact conditions which prevail in Russia. These people are the active workers back of this undertaking, but many patriotic men and women, without at all realizing the seriousness of this proposition, thinking only

of it as an effort to lessen child labor in factories, are giving countenance to it.

If adopted, this amendment would be the greatest thing ever done in America in behalf of the activities of hell. It would make millions of young people under eighteen years of age idlers in brain and body, and thus make them the devil's best workshop. It would destroy the initiative and self-reliance and manhood and womanhood of all the coming generations.

A solemn responsibility to this country and to all future generations rests upon every man and woman who understands this situation to fight, and fight unceasingly, to make the facts known to their acquaintances everywhere. Aggressive work is needed. It would be worse than folly for people who realize the danger of this situation to rest content under the belief that the amendment cannot become a part of our Constitution. The only thing that can prevent its adoption will be active, untiring work on the part of every man and woman who appreciates its destructive power and who wants to save the young people of all future generations from moral and physical decay under the domination of the devil himself.

(6) Florence Kelley, Survey Magazine (June, 1927)

Hull House was, we soon discovered, surrounded in every direction by homework carried on under the sweating system. From the age of eighteen months few children able to sit in high chairs at tables were safe from being required to pull basting threads. Out of this enquiry, amplified by Hull House residents and other volunteers, grew the volume published under the title Hull House Maps and Papers. One map showed the distribution of the polyglot peoples. Another exhibited their incomes indicated in colours, ranging from gold which meant twenty dollars or more total a week for a family, to black which was five dollars or less total family income. There were precious little gold and a superabundance of black on that income map!

The discoveries as to home work under the sweating system thus recorded and charted in 1892 led to the appointment at the opening of the legislature of 1893, of a legislative commission of enquiry into employment of women and children in manufacture, for which Mary Kenney and I volunteered as guides. With backing from labour, from Hull House, from Henry Demarest Lloyd and his friends, the Commission and the report carried almost without opposition a bill applying to manufacture, and prescribing a maximum working day not to exceed eight hours for women, girls, and children, together with child labour safeguards based on laws then existing in New York and Ohio.

When the new law took effect, and its usefulness depended on the personnel prescribed in the text to enforce it, Governor Altgeld offered the position of chief inspector to Henry Demarest Lloyd, who declined it and recommended me. I was accordingly made chief state inspector of factories, the first and so far as I know, the only woman to serve in that office in any state.

(7) Jane Addams, Newer Ideals (1907)

There are, in the United States, according to the latest census (1900), 580,000 children between the ages of ten and fourteen years, who cannot read nor write. They are not the immigrant children. They are our own native-born children. We have two millions under the age of sixteen who are earning their own livings.

(8) Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House (1910)

Our very first Christmas at Hull House, when we as yet knew nothing of child labor, a number of little girls refused the candy which was offered them as part of the Christmas good cheer, saying simply that they "worked in a candy factory and could not bear the sight of it." We discovered that for six weeks they had worked from seven in the morning until nine at night, and they were exhausted as well as satiated.

In a recent investigation of two hundred working girls it was found that only five per cent had the use of their own money and that sixty-two per cent turned in all they earned, literally every penny, to their mothers. It was through this little investigation that we first knew Marcella, a pretty young German girl who helped her widowed mother year after year to care for a large family of younger children. She was content for the most part although her mother's old-country notions of dress gave her but an infinitesimal amount of her own wages to spend on her clothes, and she was quite sophisticated as to proper dressing because she sold silk in a neighborhood department store. Her mother approved of the young man who was showing her various attentions and agreed that Marcella should accept his invitation to a ball, but would allow her not a penny toward a new gown to replace one impossibly plain and shabby. Marcella spent a sleepless night and wept bitterly, although she well knew that the doctor's bill for the children's scarlet fever was not yet paid. The next day as she was cutting off three yards of shining pink silk, the thought came to her that it would make her a fine new waist to wear to the ball. She wistfully saw it wrapped in paper and carelessly stuffed into the muff of the purchaser, when suddenly the parcel fell upon the floor. No one was looking and quick as a flash the girl picked it up and pushed it into her blouse. The theft was discovered by the relentless department store detective who, for "the sake of example," insisted upon taking the case into court. The poor mother wept bitter tears over this downfall of her "frommes Mädchen" and no one had the heart to tell her of her own blindness.

(9) Florence Kelley and Alzina Stevens, Hull House Maps and Papers (1895)

The Nineteenth Ward of Chicago is perhaps the best district in all Illinois for a detailed study of child labour, both because it contains many factories in which children are employed, and because it is the dwelling-place of wage-earning children engaged in all lines of activity.

The largest number of children to be found in any one factory in Chicago is in a caramel works in this ward, where there are from one hundred and ten to two hundred little girls, four to twelve boys, and seventy to one hundred adults, according to the season of the year. The building is a six-story brick, well-lighted, with good plumbing and fair ventilation. It has, however, no fire escape, and a single wooden stair leading from floor to floor. In case of fire the inevitable fate of the children working on the two upper floors is too horrible to contemplate.

In the stores of the West Side, large numbers of young girls are employed thirteen hours a day throughout the week, and fifteen hours on Saturday: and all efforts of the clothing-clerks to shorten the working-time by trade-union methods have hitherto availed but little.

Bennie Kelman, a Russian Jew, four years in Chicago, was found running a heavy sewing-machine by foot-power in a sweat-shop of the nineteenth ward where knee-pants are made. A health certificate was required, and the medical examination revealed a severe rupture. Careful questioning of the boy and his mother elicited the fact that he had been put to work in a boiler factory two years before, when just thirteen years old, and had injured himself lifting masses of iron. Nothing had been done for the case; no one in the family spoke any English, or knew how help could be obtained.

The legislation needed is: (1) The minimum age for work fixed at sixteen; (2) School attendance made compulsory to the same age; (3) Factory inspectors and truant officers, both men and women, equipped with adequate salaries and travelling expenses, charged with the duty of removing children from mill and workshop, mine and store, and placing them in school; 94) Ample provision for school accommodations; money supplied by the State through the school authorities for the support of such orphans, half-orphans, and children of the unemployed as are now kept out of school by destitution.

(10) Edwin Markham, Cosmopolitan (January, 1907)

In unaired rooms, mothers and fathers sew by day and by night. Those in the home sweatshop must work cheaper than those in the factory sweatshops.

And the children are called in from play to drive and drudge beside their elders.

All the year in New York and in other cities you may watch children radiating to and from such pitiful homes. Nearly any hour on the East Side of New York City you can see them - pallid boy or spindling girl - their faces dulled, their backs bent under a heavy load of garments piled on head and shoulders, the muscles of the whole frame in a long strain.

Is it not a cruel civilization that allows little hearts and little shoulders to strain under these grown-up responsibilities, while in the same city, a pet cur is jeweled and pampered and aired on a fine lady's velvet lap on the beautiful boulevards?

(11) Oscar Neebe, Autobiography of Oscar Neebe (1887)

I worked in a factory where they made oil cans and tea-caddies. This was the first place where I saw children from 8 to 12 years old work like slaves, working on machines; most every day it happened that a finger or hand was cut off, but what did it matter, they were paid off and sent home, and others would take their places. I believed that children working in factories has for the last twenty years made more cripples than the war with the south, and the cut off fingers and mangled bodies brought gold to the monopolies and manufacturers. How often has the sweat of a poor man or child paid for the silk dress of a kept woman of these men, whose only desire is "to have lots of fun and a good time."

(12) John Spargo, The Bitter Cry of the Children (1906)

The textile industries rank first in the enslavement of children. In the cotton trade, for example, 13.3 per cent of all persons employed throughout the United States are under sixteen years of age. In the Southern states, where the evil appears at its worst, so far as the textile trades are concerned, the proportion of employees under sixteen years of

age in 1900 was 25.1 per cent, in Alabama the proportion was nearly 30 per cent. A careful estimate made in 1902 placed the number of cotton-mill operatives under sixteen years of age in the Southern states at 50,000. At the beginning of 1903 a very conservative estimate placed the number of children under fourteen employed in the cotton mills of the South at 30,000, no less than 20,000 of them being under twelve. If this latter estimate of 20,000 children under twelve is to be relied upon, it is evident that the total number under fourteen must have been much larger than 30,000. According to Mr. McKelway, one of the most competent authorities in the country, there are at the present time not less than 60,000 children under fourteen employed in the cotton mills of the Southern states. Miss Jane Addams tells of finding a child of five years working by night in a South Carolina mill; Mr. Edward Gardner Murphy has photographed little children of six and seven years who were at work for twelve and thirteen hours a day in Alabama mills. In Columbia, S. C., and Montgomery, Ala., I have seen hundreds of children, who did not appear to be more than nine or ten years of age, at work in the mills, by night as well as by day.

One evening, not long ago, I stood outside of a large flax mill in Paterson, New Jersey, while it disgorged its crowd of men, women, and children employees. All the afternoon, as I lingered in the tenement district near the mills, the comparative silence of the streets oppressed me. There were many babies and very small children, but the older children, whose boisterous play one expects in such streets, were wanting.

At six o'clock the whistles shrieked, and the streets were suddenly filled with people, many of them mere children. Of all the crowd of tired, pallid, and languid-looking children I could only get speech with one, a little girl who claimed thirteen years, though she was smaller than many a child of ten. Indeed, as I think of her now, I doubt whether she would have come up to the standard of normal physical development either in weight or stature for a child of ten. One learns, however, not to judge the ages of working children by their physical appearance, for they are usually behind other children in height, weight, and girth of chest, - often as much two or three years. If my little Paterson friend was thirteen, perhaps the nature of her employment will explain her puny, stunted body. She works in the "steaming room" of the flax mill. All day long, in a room filled with clouds of steam, she has to stand barefooted in pools of water twisting coils of wet hemp. When I saw her she was dripping wet though she said that she had worn a rubber apron all day. In the coldest evenings of winter little Marie, and hundreds of other little girls, must go out from the superheated steaming rooms into the bitter cold in just that condition. No wonder that such children are stunted and underdeveloped.