New York City

The New York area was first discovered by the Europeans when Henry Hudson, the English captain of the Dutch East India Company vessel De Halve Maen, laid anchor at Sandy Hook, before sailing up what is now known as the Hudson River.

In 1614 Dutch merchants established a trading post at Fort Orange. Ten years later thirty families came from Holland to establish a settlement that became known as New Netherland. The Dutch government gave exclusive trading rights to the Dutch West India Company and over the next few years other colonists arrived a large settlement was established on Manhattan Island.

Peter Minui, who became governor of New Netherland, purchased the island from Native Americans in 1626 for $24 worth of trinkets, beads and knives. The chief port on Manhattan was named New Amsterdam. To encourage further settlement, the Dutch West India Company offered free land along the Hudson River. Families who came from Holland to establish estates in this area included the Roosevelts, the Stuyvesants and the Schuylers.

Peter Stuyvesant became governor in 1646 and during his eighteen year administration, the population grew from 2,000 to 8,000. Descendants of these early settlers included three presidents of the United States: Martin Van Buren (1837-41), Theodore Roosevelt (1901-09) and Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-45).

In 1664 the English fleet arrived and demanded the surrender of the New Netherlands. Peter Stuyvesant wanted to fight but without the support of the other settlers, he was forced to allow the English to take control of the territory. New Amsterdam was now renamed New York, after the Duke of York (the future James II). Other name changes included Albany (Fort Orange), Kingston (Wiltwyck) and Wilmington (Fort Christina). New York City occupies Manhattan and Staten islands, the western end of Long Island, several islands in New York Harbor and Long Island Sound and a portion of the mainland.

Fernando Wood, a leading figure in the Tammary Society, served as mayor of the city (1855-59 and 1859-61). Wood was considered to be corrupt and was severely criticised for his opposition to the American Civil War. Wood made several speeches attacking President Abraham Lincoln and was blamed for causing the Draft Riots in July, 1863.

Samuel Gompers arrived in New York in 1863: "New York in those days had no skyscrapers. Horse tram cars ran across town. The buildings were generally small and unpretentious. Then, as now, the East Side was the home of the latest immigrants who settled in colonies making the Irish, the German, the English, and the Dutch, and the Ghetto districts. Father began making cigars at home and I helped him. Our house was just opposite a slaughter house. All day long we could see the animals being driven into the slaughter-pens and could hear the turmoil and the cries of the animals. The neighborhood was filled with the penetrating, sickening odor."

In 1870 William Tweed, with the support of the Tammary Society, was appointed as commissioner of public works in New York. This enabled Tweed to carry out wholesale corruption. For example, he purchased 300 benches for $5 each and resold them to the city for $600. Tweed also organised the building of City Hall Park. Originally estimated to cost $350,000, by the time it was finished, expenditure had reached $13,000,000.

Information about Tweed's corrupt activities were passed to Thomas Nast, a cartoonist working for Harper's Weekly. Nast now began a campaign to expose Tweed's corruption. Tweed was furious and told the editor: "I don't care a straw for your newspaper articles, my constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damned pictures."

On 21st July, the New York Times published the contents of the New York County ledger books. This revealed that thermometers were costing $7,500 and brooms were being charged at a staggering $41,190 apiece. Tweed's friends were commissioned to do the work. George Miller, a carpenter, was paid $360,747 for a month's labour, whereas James Ingersoll received $5,691,144 for furniture and carpets.

In 1871 Samuel Tilden established a committee to look into Tweed's activities. Jimmy O'Brien, the sheriff of New York, believed Tweed was not paying him enough money for his services. Disgruntled, he passed documents to Tilden's committee. Tweed was arrested and found guilty of corruption, was sentenced to 12 years in jail. William Grace (1880-88) was another mayor who was investigated for corruption.

John Kelly and Richard Croker, of the Tammary Society held power in New York after the removal of William Tweed from power. They held various posts and were constantly being accused of financial irregularities. Charles Parkhurst, the president of the Society for the Prevention of Crime, led the campaign against city corruption, but Croker remained in power until 1901 when he was defeated by Seith Low.

The journalist, Lincoln Steffens, has argued that Low was a successful mayor: "The mayor of New York, Seth Low, was a business man and the son of a business man, rich, educated, honest, and trained to his political job. Seth Low and his party in power and his backers were not radicals in any sense. Mr. Low himself was hardly a liberal; he was what would be called in England a conservative. He accepted the system; he took over the government as generations of corrupters had made it, and he was trying, without any fundamental change, and made it an efficient, orderly business-like organization for the protection and the furtherance of all business, private and public." His good work was continued by John Mitchel (1913-17) and Fiorello La Guardia (1932-1944).

In the 19th century New York became the home of an increasing number of European immigrants. In 1890 over 640,000 people living in the city had been born in Europe. This was 42 per cent of the 1,515,000 population and included large numbers from Germany (211,000), Ireland (190,000), Russia (49,000), Austria-Hungary (48,000), Italy (40,000) and England (36,000).

Jacob Riis wrote about the migration to New York in his book, How the Other Half Lives (1890): "Ever since the civil war New York has been receiving the overflow of coloured population from the Southern cities. In the last decade this migration has grown to such proportions that it is estimated that our Blacks have quite doubled in number since the Tenth Census.... Cleanliness is the characteristic of the Negro in his new surroundings, as it was his virtue in the old. In this respect he is immensely the superior of the lowest of the whites, the Italians and the Polish Jews, below whom he has been classed in the past in the tenant scale. This was shown by an inquiry made last year by the Real Estate Record. It proved agents to be practically unanimous in the endorsement of the Negro as a clean, orderly, and profitable tenant. Poverty, abuse, and injustice alike the Negro accepts with imperturbable cheerfulness."

By 1910 the number of people living in the city that had been born in Europe had increased to 1,944,000. The major groups now came from Russia (484,000), Italy (341,000), Germany (278,000), Austria-Hungary (267,000) and Ireland (253,000).

Of the 5,400,000 immigrants who arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1860, about 3,700,000 entered in New York. Ellis Island, an area of about 27 acres 1.6 km southwest of Manhattan Island, served as the country's major immigration station between 1892 and 1924. During this period and estimated 17 million people were processed by the immigration authorities. From 1943 until 1954 Ellis Island was used as a detention station for aliens and deportees.

New York City occupies Manhattan and Staten islands, the western end of Long Island, several islands in New York Harbor and Long Island Sound and a portion of the mainland. The city area comprises 304 square miles (787 square km) and has a population over 7,300,000 and is the largest urban agglomeration in the United States.

Primary Sources

(1) Samuel Gompers and his family settled in New York after arriving in 1863.

New York in those days had no skyscrapers. Horse tram cars ran across town. The buildings were generally small and unpretentious. Then, as now, the East Side was the home of the latest immigrants who settled in colonies making the Irish, the German, the English, and the Dutch, and the Ghetto districts. Father began making cigars at home and I helped him. Our house was just opposite a slaughter house. All day long we could see the animals being driven into the slaughter-pens and could hear the turmoil and the cries of the animals. The neighborhood was filled with the penetrating, sickening odor.

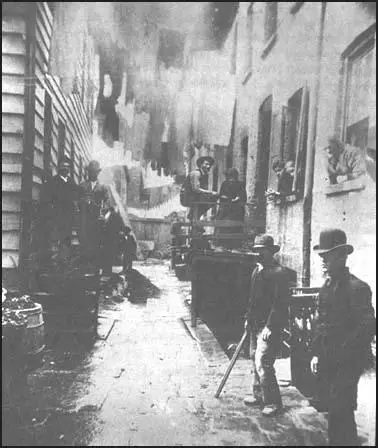

(2) Jacob Riis wrote about New york in How the Other Half Lives (1890)

On either side of the narrow entrance to Bandits' Roost is "the Bend". Abuse is the normal condition of "the Bend," murder is everyday crop, with the tenants not always the criminals. In this block between Bayard, Park, Mulberry, and Baxter Streets, "the Bend" proper, the late Tenement House Commission counted 155 deaths of children in a specimen year (1882). Their percentage of the total mortality in the block was 68.28, while for the whole city the proportion was only 46.20. In No. 59 next to Bandits' Roost, fourteen persons died that year, and eleven of them were children; in No. 61 eleven, and eight of them not yet five years old.

(3) Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives (1890)

Ever since the civil war New York has been receiving the overflow of coloured population from the Southern cities. In the last decade this migration has grown to such proportions that it is estimated that our Blacks have quite doubled in number since the Tenth Census. Whether the exchange has been of advantage to the Negro may well be questioned. Trades of which he had practical control in his Southern home are not open to him here. I know that it may be answered that there is no industrial proscription of colour; that it is a matter of choice. Perhaps so. At all events he does not choose them. How many coloured carpenters or masons has anyone seen at work in New York?

Cleanliness is the characteristic of the Negro in his new surroundings, as it was his virtue in the old. In this respect he is immensely the superior of the lowest of the whites, the Italians and the Polish Jews, below whom he has been classed in the past in the tenant scale. This was shown by an inquiry made last year by the Real Estate Record. It proved agents to be practically unanimous in the endorsement of the Negro as a clean, orderly, and profitable tenant.

Poverty, abuse, and injustice alike the Negro accepts with imperturbable cheerfulness. His philosophy is of the kind that has no room for repining. Whether he lives in an Eighth Ward barrack or in a tenement with a brown-stone front and pretensions to the tile of "flat," he looks at the sunny side of life and enjoys it. He loves fine clothes and good living a good deal more than he does a bank account.

(4) Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives (1890)

The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children maintains five of these boys' lodging-houses, and one for girls, in the city. The Duane Street Lodging House alone has sheltered since its foundation in 1855 nearly a quarter of a million different boys. In all of the lodging-houses together, 12,153 boys and girls were sheltered and taught last year. Besides these, the Society has established and operates in the tenement districts twenty-one industrial schools, co-ordinate with the public schools in authority, for the children of the poor who cannot find room in the city's school-houses, or are too ragged to go there; two free reading-rooms, a dress-making and typewriting school and a laundry for the instruction of girls; a sick-children's mission in the city and two on the sea-shore, where poor mothers may take their babies; a cottage by the sea for crippled girls, and a brush factory for crippled boys in Forty-fourth Street.

The Italian school in Leonard Street, alone, had an average attendance of over six hundred pupils last year. The daily average attendance at all of them was 4,105, while 11,331 children were registered and taught. When the fact that there were among these 1,132 children of drunken parents, and 416 that had been found begging in the street, is contrasted with the showing of $1,337.21 deposited in the school savings banks by 1,745 pupils, something like an adequate idea is gained by the scope of the Society's work in the city.

(5) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

The mayor of New York, Seth Low, was a business man and the son of a business man, rich, educated, honest, and trained to his political job. Seth Low and his party in power and his backers were not radicals in any sense. Mr. Low himself was hardly a liberal; he was what would be called in England a conservative. He accepted the system; he took over the government as generations of corrupters had made it, and he was trying, without any fundamental change, and made it an efficient, orderly business-like organization for the protection and the furtherance of all business, private and public.

(6) Seth Low, who was later to become mayor of New York, wrote about the problems of the city in American City Government (1891)

It is estimated that the population of New York City contains 80 per cent of people who either are foreign-born or who are the children of foreign-born parents. Consequently, in a city like New York, the problem of learning the art of government is handed over to a population that begins in point of experience very low down. It many of the cities of the United States, indeed in almost all of them, the population not only is thus largely untrained in the art of self-government but it is not even homogeneous; so that an American city is confronted, not only with the necessity of instructing large and rapidly growing bodies of people in the art of government but it is compelled at the same time to assimilate strangely different component parts into an American community. It will be apparent to the student that either of these functions by itself would be difficult enough. When both are found side by side, the problem is increasingly difficult as to each. Together they represent a problem such as confronts no city in Europe.

(7) Angelo Pellegrini, stayed on Ellis Island for three days when her family arrived from Italy.

We lived there for three days - mother and we five children, the youngest of whom was three years old. Because of the rigorous physical examination that we had to submit to, particularly of the eyes, there was this terrible anxiety that one of us might be rejected. And if one of us was, what would the rest of the family do? My sister was indeed momentarily rejected; she had been so ill and had cried so much that her eyes were absolutely bloodshot, and mother was told, "Well, we can't let her in." but fortunately, mother was an indomitable spirit and finally made them understand that if her child had a few hours' rest and a little bite to eat she would be all right. In the end we did get through.

(8) Maxim Gorky wrote to Leonid Andreev about his firt impressions of New York (11th April, 1906)

It is such an amazing fantasy of stone, glass, and iron, a fantasy constructed by crazy giants, monsters longing after beauty, stormy souls full of wild energy. All these Berlins, Parises, and other "big" cities are trifles in comparison with New York. Socialism should first be realized here - that is the first thing you think of, when you see the amazing houses, machines, etc.

(9) Jessica Mitford, Hons and Rebels (1960)

Those first days in New York were filled with opportunities to check our prior conceptions of America against reality. The Times-Square-Broadway-42nd Street area lived up to all expectations, with its bright, movie-like quality and the added musical comedy touch provided by pickets for ever circling in front of the Brass Rail restaurant delivering in unison their eternal message: "Brass Rail's on Strike Please Pass By."

Of course we were told that New York is "not typical" of America how untypical we were not then in a position to judge - but we did get the impression there was a distinct New York personality. The unique feature of this personality seemed the bright spark of momentary interest lit in New Yorkers by the most casual of contacts.

Roaming the streets of New York, we encountered many examples of this delightful quality of New Yorkers, forever on their toes, violently, restlessly involving themselves in the slightest situation brought to their attention, always posing alternatives, always ready with an answer or an argument.

(10) William Patterson, The Man Who Cried Genocide (1971)

The New York skyline was amazing! The towering buildings were like the castles of giants. They seemed to come right down to the water's edge. I had something of the feeling of awe I had when I first saw the giant redwood trees in California.

We tied up at one of the city docks and I stepped onto the streets of New York. Fearful of the intricacies of subway travel, I took a taxi to Harlem and went at once to the house the young man had told me about. It was on a beautiful tree-lined street, 139th between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. I almost had to show my law degree before I got the room at ten dollars a week.

I was now living among the upper classes. Harlem was at that time being taken over by the Negro people as they moved uptown from Hell's Kitchen. Blacks were seeking better conditions, as escape from the terrible downtown slum. Class stratification was becoming noticeable. Some Negroes were already trying to find a way to share in the exploitation of their Black brothers. Speculation in dwelling houses was on a grand scale.

Strivers' Row was designed by Leiand Stanford White for white middle-class occupancy a generation or two before. The houses were being taken over by Negro doctors, lawyers, social climbers - all seeking not only to better their living conditions but also to establish themselves in a prestigious location. It was one of the economic phases of what was sometimes called "the Negro Renaissance." Harlem, the new Negro community, was offering a market in which super-exploitation was the order of the day. Negro merchants were trying to find a place near the top; others were trying to gain a foothold on the political ladder. The black literati were stirring. Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, the artist Aaron Douglas, and a host of poets, writers and musicians were emerging.