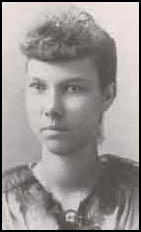

Kate Richards

Kate Richards was born in Ada, Kansas, on 26th March, 1877. After a brief schooling in Nebraska, she became an apprentice machinist in Kansas City. Deeply religious, Richards joined the Women's Christian Temperance Union.

Richards was influenced by the books on overcoming poverty by Henry George and Henry Demarest Lloyd. However, it was a speech made by Mary 'Mother' Jones and meeting Julius Wayland, the editor of Appeal to Reason, that converted her to socialism.

Richards joined the Socialist Labor Party in 1899 and two years later the Socialist Party of America. In 1902 she married Francis O'Hare and they spent their honeymoon lecturing on socialism. This included visits to Britain, Canada and Mexico. Richards wrote the successful socialist novel, What Happened to Dan? (1904) and with her husband edited the National Rip-Saw, a radical journal published in St. Louis. In 1910 she unsuccessfully ran for the Kansas Congress.

Richards believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and argued that the USA should remain neutral. In 1917 Richards became chair of the Committee on War and Militarism and toured the country making speeches against the war.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the government passed the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to make speeches that undermined the war effort. Criticised as unconstitutional, the act resulted in the imprisonment of many members of the anti-war movement including 450 conscientious objectors.

In July, 1917, Richards was sentenced to five years for making an anti-war speech in North Dakota. The judge told her: "This is a nation of free speech; but this is a time for sacrifice, when mothers are sacrificing their sons. Is it too much to ask that for the time being men shall suppress any desire which they may have to utter words which may tend to weaken the spirit, or destroy the faith or confidence of the people?"

she kept with her after being imprisoned in 1917

While in prison Richards published two books, Kate O'Hare's Prison Letters (1919) and In Prison (1920). After a nationwide campaign President Calvin Coolidge commuted her sentence. In 1922 Richards organized the Children's Crusade, a march on Washington, by children of those anti-war agitators still in prison.

Richards and her husband settled in Leesville, Louisiana, where they joined the Llano Cooperative Colony, published the American Vanguard and helped establish the Commonwealth College. Richards also took a keen interest in prison reform and carried out a national survey of prison labour (1924-26).

In 1928 Richards married Charles Cunningham, a San Francisco lawyer. She remained active in politics and in 1934 helped Upton Sinclair in his socialist campaign to become the governor of California. Kate Richards, who was assistant director of the California Department of Penology (1939-40) died in Benicia, California, on 10th January, 1948.

Primary Sources

(1) Kate Richards O'Hare, How I Became a Socialist Agitator (1908)

Seeing so much poverty and want and suffering, threw my whole soul into church and religious work. I felt somehow that the great, good God who had made us could not have want only abandoned his children to such hopeless misery and sordid suffering. There was nothing uplifting in it, nothing to draw the heart nearer to him, only forces that clutched and dragged men and women down into the abyss of drunkenness and vice. Perhaps he had only overlooked those miserable children of the poor in the slums of Kansas City, and if we prayed long and earnestly and had enough of religious zeal he might hear and heed and pity. For several years I lived through that Gethsemane we all endure who walk the path from religious fanaticism to cold, dead, material cynicism with no ray of sane life-philosophy to light it.

I saw drunkenness and the liquor traffic in all the bestial, sordid aspects it wears in the slums, and with it the ever-close companion of prostitution in its most disgusting and degraded forms. I believed, for the good preachers and temperance workers who led me said, that drunkenness and vice caused poverty and I struggled and worked, with only the heart-breaking zeal that an intense young girl can work, to destroy them. But in spite of all we could do the corner saloon still flourished, the saloon-keeper still controlled the government of the city and new inmates came to fill the brothel as fast as the old ones were carried out to the Potter's field, and the grim grist of human misery and suffering still ground on in defiance to church and temperance society and rescue mission.

About this time father embarked in the machine shop business and I added to my various experiences that of a woman forced into the business world there to have every schoolday illusion rudely shattered, and forced to see business life in its sordid nakedness. Possibly because I hated ledgers and daybooks and loved mechanics, and possibly because I really wanted to study the wage-worker in his own life, I made life so miserable for the foreman and all concerned that they finally consented to let me go into the shop as an apprentice to learn the trade of machinist. For more than four years I worked at the forge and lathe and bench side by side with some of the best mechanics of the city and some of the noblest men I have ever known. The work was most congenial and I learned for the first time what absorbing joy there can be in labor, if it be a labor that one loves.

Even before my advent into the shop I had begun to have some conception of economics. I had read Progress and Poverty, Wealth vs. Commonwealth, Caesar's Column, and many such books. Our shop being a union one I naturally came in contact with the labor union world and was soon as deeply imbued with the hope trade unionism held out, as I had been with religious zeal. After a while it dawned upon me in a dim and hazy way that trade unionism was something like the frog who climbed up to the well side two feet each day and slipped back three each night. Every victory we gained seemed to give the capitalist class a little greater advantage.

One night while returning from a union meeting, , I heard a man talking on the street corner of the necessity of workingmen having a political party of their own. I asked a bystander who the speaker was and he replied, "a Socialist." Of course, if he had called him anything else it would have meant just as much to me, but somehow I remembered the word. A few weeks later I attended a ball given by the Cigar Maker's union, and Mother Jones spoke. Dear old Mother! That is one of the mile-posts in my life that I can easily locate. Like a mother talking to her errant boys she taught and admonished that night in words that went home to every heart. At last she told them that a scab at the ballot-box was more to be despised than one at the factory door, that a scab ballot could do more harm than a scab bullet; that workingmen must support the political party of their class and that the only place for a sincere union man was in the Socialist party. Here was that strange new word again coupled with the things I had vainly tried to show my fellow unionists.

I hastily sought out "Mother" and asked her to tell what Socialism was, and how I could find the Socialist party. With a smile she said, "Why, little girl, I can't tell you all about it now, but here are some Socialists, come over and get acquainted." In a moment I was in the center of an excited group of men all talking at once, and hurling unknown phrases at me until my brain was whirling. I escaped by promising to "come down to the office tomorrow and get some books." The next day I hunted up the office and was assailed by more perplexing phrases and finally escaped loaded down with Socialist classics enough to give a college professor mental indigestion. For weeks I struggled with that mass of books only to grow more hopelessly lost each day. At last down at the very bottom of the pile I found a well worn, dog-eared, little book that I could not only read, but understand, but to my heart-breaking disappointment it did not even mention Socialism. It was the Communist Manifesto, and I could not understand what relation it could have to what I was looking for.

I carried the books back and humbly admitted my inability to understand them or grasp the philosophy they presented. As the men who had given me the books explained and expostulated in vain, a long, lean, hungry looking individual unfolded from behind a battered desk in the corner and joined the group. With an expression more forceful than elegant he dumped the classics in the corner, ridiculed the men for expecting me to read or understand them, and after asking some questions as to what I had read gave me a few small booklets. Merrie England and Ten Men of Money Island, Looking Backward, and Between Jesus and Caesar, and possibly half a dozen more of the same type. The hungry looking individual was Julius Wayland, and the dingy office the birthplace of the Appeal to Reason.

(2) Kate Richards O'Hare, wrote an article on child labour that was published in Appeal to Reason. The material on Roselie Randazzo, an Italian immigrant, was collected while she worked in an artificial flower factory in New York City (19th November, 1904)

Walking up the steps I came upon Roselie, the little Italian girl who sat next to me at the long work table. Roselie, whose fingers were the most deft in the shop and whose blue-black curls and velvety eyes I had almost envied as I often wondered why nature should have bestowed so much more than an equal share of beauty on the little Italian. Overtaking her I noticed she clung to the banister with one hand and held a crumpled mitten to the lips with the other. As we entered the cloak room she noticed my look of sympathy and weakly smiling said in broken English. "Oh, so cold! It hurta me here," and she laid her hand on her throat.

Seated at the long table the forelady brought a great box of the most exquisite red satin roses, and glancing sharply at Roselie said; "I hope you're not sick this morning; we must have these roses and you are the only one who can do them; have them ready by noon."

Soon a busy hum filled the room and in the hurry and excitement of my work I forgot Roselie until a shrill scream from the little Jewess across the table reached me and I turned in time to see Roselie fall forward among the flowers. As I lifted her up the hot blood spurted from her lips, staining my hands and spattering the flowers as it fell.

The blood-soaked roses were gathered up, the forelady grumbling because many were ruined, and soon the hum of industry went on as before. But I noticed that one of the great red roses had a splotch of red in its golden heart, a tiny drop of Rosie's heart's blood and the picture of the rose was burned in my brain.

The next morning I entered the grim, gray portals of Bellevue Hospital and asked for Roselie. "Roselie Randazzo," the clerk read from the great register. "Roselie Randazzo, seventeen; lives East Fourth street; taken from Marks' Artificial Flower Factory; hemorrhage; died 12.30 p.m." When I said that it was hard that she should die, so young and so beautiful, the clerk answered: "Yes, that's true, but this climate is hard on the Italians; and if the climate don't finish them the sweat shops or flower factories do," and then he turned to answer the questions of the woman who stood beside me and the life story of the little flower maker was finished.

(3) Kate Richards O'Hare, letter to the Appeal to Reason on the death of Julius Wayland (23rd November, 1912)

We have no idle, vain, regrets; for who are we to judge, or say that he has shirked his task or left some work undone? No eyes can count the seed that he has sown, the thoughts that he has planted in a million souls now covered deep beneath the mold of ignorance which will not spring into life until the snows have heaped upon his grave and the sun of springtime comes to reawake the sleeping world.

Sleep on, our comrade; rest your weary mind and soul; sleep and deep, and if in other realms the boon is granted that we may again take up our work, you will be with us and give us your strength, your patience and your loyalty to your fellow men. We bring no ostentatious tributes of our love, we spend not gold for flowers for your tomb, but with hearts that rejoice at your deliverance offer a comrade's tribute to lie above your breast - the red flag of human brotherhood.

(4) Trial judge sentencing Kate Richards O'Hare to prison for five years for making an anti-war speech in North Dakota (July, 1917)

This is a nation of free speech; but this is a time for sacrifice, when mothers are sacrificing their sons. Is it too much to ask that for the time being men shall suppress any desire which they may have to utter words which may tend to weaken the spirit, or destroy the faith or confidence of the people?

(5) Eugene Debs, speech in Canton, Ohio (16th June 1918)

The other day they sentenced Kate Richards O'Hare to the penitentiary for five years. Think of sentencing a woman to the penitentiary simply for talking. The United States, under plutocratic rule, is the only country that would send a woman to prison for five years for exercising the right of free speech. If this be treason, let them make the most of it.

Let me review a bit of history in connection with this case. I have known Kate Richards O'Hare intimately for twenty years. I am familiar with her public record. Personally I know her as if she were my own sister. All who know Mrs. O'Hare know her to be a woman of unquestioned integrity. And they also know that she is a woman of unimpeachable loyalty to the Socialist movement. When she went out into North Dakota to make her speech, followed by plain-clothes men in the service of the government intent upon effecting her arrest and securing her prosecution and conviction - when she went out there, it was with the full knowledge on her part that sooner or later these detectives would accomplish their purpose. She made her speech, and that speech was deliberately misrepresented for the purpose of securing her conviction. The only testimony against her was that of a hired witness. And when the farmers, the men and women who were in the audience she addressed - when they went to Bismarck where the trial was held to testify in her favor, to swear that she had not used the language she was charged with having used, the judge refused to allow them to go upon the stand. This would seem incredible to me if I had not had some experience of my own with federal courts.

(6) Kate Richards O'Hare, Appeal to Reason (24th July, 1920)

We Socialists knew the relation of profits to war and we insisted on telling the truth about it. We talked war and profits, war and profits, war and profits until the administration was compelled, in sheer self-defense to attempt to squelch us. First the administration violated the constitutional provision for free press and by the stroke of a pen destroyed the greater portion of the Socialist press. But we could still talk if we could not publish newspapers, and we did talk and talk and talk. And the best method the limited intelligence of the administration could devise for squelching talking Socialists was to send them to prison.

In my case it was a frightful strain on the "brains of the administration" to find some plausible excuse for sending me to prison. With the best sleuthing the Department of Justice could do it was compelled to admit that I had violated no law; I was of American blood for many generations; my family had always been properly patriotic and had participated in every war the United States had ever waged; my public utterances and private life proved that I was not pro-German and was most emphatically pro-American; I was entirely "nice" and "respectable" and "ladylike" and I had managed to amble along to comfortable middle age with the same husband and children I started with. In fact I had but one vice - I did insist on telling the truth about war and politics. And war and profits was the one subject the Democratic administration dared not permit me to discuss.

So many people have marveled that I should have traveled all over the country telling the truth, as I saw it, about war and profits unmolested, until I landed in a little, unknown town in the north-west, and there to have been "framed", arrested, tried, convicted and sent to prison. But there is really nothing marvelous about it, I was simply more dangerous to the capitalists, the war profiteers and the Democratic Party in the northwest than in any other section of the United States.

(7) In July, 1920, the journal, Appeal to Reason , reported on Kate Richards O'Hare visiting Eugene Debs in prison.

In a visit full of dramatic incidents, Kate Richards O'Hare visited Eugene V. Debs in the Federal penitentiary in Atlanta on 2nd July, to carry to him the love of Socialists everywhere.

Kate O'Hare was ushered into the prison; the two comrades met and embraced; Kate Richards O'Hare recently freed from the Federal prison and Eugene V. Debs in prison garb with nine years of prison life before him, with both his hands still upon her shoulders, said, "How happy I am to see you free, Kate."

"Your coming here is like a new sunlight to me. Tell me about your prison experiences," said Debs. She answered, "Gene, I am not thinking of myself, but of little Mollie Steimer who now occupies my cell at Jefferson City and of her appalling sentence of fifteen years. She is a nineteen-year-old little girl, smaller in stature than my Kathleen, whose sole crime is her love for the oppressed.

Then Kate opened her leather card-case and showed Debs her family group picture which she had carried with her during the fourteen months of prison life. The sight of that picture had afforded her much consolation through the hours of dreaded prison silence and monotony.