William Haywood

William Dudley Haywood, the son of a South African woman and a Kentucky miner, was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, on 4th February, 1869. When he was a young boy he lost an eye in an accident. His parents were poor and at the age of nine he began work down a mine in Winnemucca, Nevada. While working as a miner Haywood met Patrick Reynolds, a member of the Knights of Labor. Reynolds was to have a lasting influence on Haywood's political views.

Haywood married Jane Minor, the daughter of a rancher, and for a whilhad a homestead in Idaho. His wife suffered from poor health and the venture was not successful. In 1896 Haywood found work in the Blaine mine in Silver City, and soon afterwards joined the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Haywood became active in the union campaigns to increase wages and to bring an end to child labour in the mines. According to his biographer, Joseph R. Conlin: "He was an excellent administrator, maintaining virtually total organizational control of the town, supervising the hospital, and negotiating peacefully with employers.... Over six feet tall, well over two hundred pounds, and with a glowering glass eye, Haywood soon earned a reputation as a resolute crisis leader."

In 1901 Haywood was elected secretary-treasurer of the WFM. Later that year he joined the American Socialist Party. In 1901 Haywood was elected secretary-treasurer of the WFM. Later that year he joined the American Socialist Party. Haywood also edited the Miners' Magazine, the journal of the WFM, and he used this position to promote the idea of socialism and argued that America should become a cooperative commonwealth. Other trade union leaders such as Eugene V. Debs and Daniel De Leon were also converted to socialism.

Haywood and his political friends were unhappy with the conservative approach of the American Federation of Labour and on 27th June, 1905, they held a meeting in Chicago. Those who attended the meeting included Eugene V. Debs, Daniel De Leon, Mother Jones, Lucy Parsons and Charles Moyer. At the convention it was decided to form the radical labour organisation, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

In 1905 representatives of 43 groups who opposed the policies of American Federation of Labour, formed the radical labour organisation, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). At first its three main leaders were William Haywood, Daniel De Leon and Eugene V. Debs. Other important figures in the movement included Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Lucy Parsons, Hubert Harrison, Carlo Tresca, Joseph Ettor, Arturo Giovannitti, William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, Joe Haaglund Hill, Tom Mooney, Floyd B. Olson, James Larkin, James Connolly, Frank Little and Ralph Chaplin.

In 1905 Haywood was charged with taking part in the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho. Steunenberg was much hated by the trade union movement after using federal troops to help break strikes during his period of office. Over a thousand trade unionists and their supporters were rounded up and kept in stockades without trial.

James McParland, from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was called in to investigate the murder. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire.

McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named Hayward and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Fed You all a Thousand Years (1918)

Charles Darrow, a man who specialized in defending trade union leaders, was employed to defend Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Harry Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry. During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard and were all acquitted.

In 1908 the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) split into two factions. The group headed by Eugene V. Debs advocated political action through the Socialist Party and the trade union movement, to attain its goals. The other faction, led by Haywood, believed that general strikes, boycotts and even sabotage were justified in order to achieve its objectives. Haywood's views prevailed and Debs, and others who thought like him, left the organisation.

George Seldes interviewed Haywood and Joe Hill in 1912: "When Bill Hayward came to the coal and iron capital of America, Ray Springle and I went to his headquarters, not for news stories, which we knew would never be published, but out of interest in the new labor movement, the Industrial Workers of the World. And so, by chance along with its new leaders we met the ballad-maker of the IWW, Joe Hill."

Ramsay MacDonald saw Haywood make a speech during this period: "William Haywood is the embodiment of the Sorel philosophy, roughened by the American industrial and civic climate, a bundle of primitive instincts, a master of direct statement. He is useless on committee; he is a torch amongst a crowd of uncritical and credulous workmen. I saw him at Copenhagen, amidst the leaders of the working-class movements drawn from the whole world, and there he was dumb and unnoticed; I saw him addressing a crowd in England, and there his crude appeals moved his listeners to wild applause. He made them see things, and their hearts bounded up to be up and doing."

Haywood remained active in the Socialist Party and was seen as the leader of the radical left. Eventually, in 1912 Victor Berger and Morris Hillquit, the leaders of the right-wing, gained control and expelled Haywood and his followers. As Joseph R. Conlin explains: "They disapproved of his militant rhetoric on behalf of sabotage, which they interpreted as meaning violence, and by his disdain for the electoral approach to socialism."

In January 1912 the America Woolen Company reduced the wages of its workers. This caused a walk-out and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), who had been busy recruiting workers into the union, took control of the dispute. The IWW formed a strike committee with two representatives from each of the nationalities in the industry. It was decided to demand a 15 per cent increase in wages, double-time for overtime work and a 55 hour week.

Haywood, Carlo Tresca and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn now arrived in Lawrence and took over the running of the strike. On 12th March, 1912, the America Woolen Company acceded to all the strikers' demands. By the end of the month, the rest of the other textile companies in Lawrence also agreed to pay the higher wages.

In 1913 Haywood and the Industrial Workers of the World helped organize the silk workers at the Paterson Silk Mills. During the dispute over 3,000 pickets were arrested, most of them received a 10 day sentence in local jails. Two workers were killed by private detectives hired by the mill workers. These men were arrested but were never brought to trial. However, the strike fund was unable to raise enough money and in July, 1913, the workers were starved into submission.

Bill Haywood during the Paterson Silk Mill (1913)

Haywood replaced Vincent St. John as secretary-treasurer of the IWW in 1913. By this time, the IWW had 100,000 members. In 1914, one of the leaders of the IWW, Joe Haaglund Hill was accused of the murder of a Salt Lake City businessman. Convicted on circumstantial evidence and despite of mass protests, Hill was shot by a firing squad on 19th November, 1915. Whereas another IWW leader, Frank Little, was lynched in Butte, Montana.

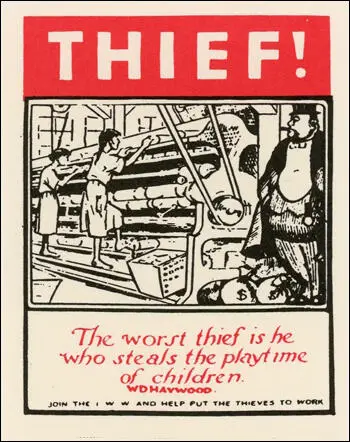

At this time there were over two million children under the age of sixteen in paid employment in the United States. Haywood joined other radicals such as Kate Richards O'Hare, Eugene Debs, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Norman Hapgood, Jane Addams, Lewis Hine, Ellen Gates Starr, Robert Hunter, Henry Damerest Lloyd, Julia Lathrop, Lillian Wald, Alzina Stevens, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Florence Kelley, Mary McDowell, Alice Hamilton and Sophonisba Breckinridge to campaign against child labour: Haywood was reported as saying: "The worst thief is he who steals the playtime of children."

Haywood and the Industrial Workers of the World opposed the United States becoming involved in the First World War. He issued a statement on behalf of the IWW: "With the European war for conquest and exploitation raging and destroying the lives, class consciousness and unity of the workers, clouding the main issues, we openly declare ourselves the determined opponents of all nationalistic sectionalism, or patriotism, and the militarism preached and supported by our one enemy, the capitalist class. We condemn all wars, and for the prevention of such, we proclaim the anti-militarist propaganda in time of peace and, in time of war, the General Strike in all industries."

Haywood did not agitate against it nor forbid members to comply with the draft. Nevertheless, politicians and employers' associations attacked the IWW as disloyal and dangerous. In a series of raids resulted in the indictment of Haywood and most of the union's leadership under the Espionage Act. After a long trial in Chicago, Haywood was sentenced to a fine of $20,000 and twenty years' imprisonment.

In March 1921, Haywood jumped bail and fled to the Soviet Union, while most of his co-defendants languished in prison. As Joseph R. Conlin has pointed out: "IWW morale was shattered. Although individuals remembered him affectionally and excused his action without justifying it, his influence on the American Left had all but vanished."

The Russian government placed Haywood in charge of the Kuzbas coal-mining colony. He occasionally visited Walter Duranty, who worked for the New York Times and was based in Moscow. Haywood told Duranty: "The trouble with us old Wobblies is that we all know how to sock scabs and mine-guards and policemen or make tough fighting speeches to a crowd of strikers but we aren't so long on this ideological theory stuff as the Russians." Haywood predicted that the Soviet leadership would eventually split over these issues. "There's something in that but it goes far deeper. These Russians attach the hell of a lot to ideological theory, and mark my words, if they're not careful they'll come to blows about it one of these days. Don't you know yet that most of them would sooner talk than work, or even eat?"

Haywood also became friendly with another journalist, Eugene Lyons. In his book, Assignment in Utopia (1937), he wrote: "Though stupidly regarded by so many as un-American, Haywood's every nerve and muscle was rooted in the American soil, and the movement which he started and led - a movement of hoboes, drifters, unskilled workers, lumberjacks and miners - was likewise authentically American in a sense that made it incomprehensible to foreign students. He had fled to Russia with other IWW men while out on bail and was therefore forever cut off from his native land. This robust, two-fisted American, essentially democratic and idealistic in his instincts, found the Bolshevik system of impersonal brutality hateful and fumed inwardly because he could say and do nothing about it. After a lifetime of fighting what he considered the delusions of political action, he could not swallow a super-state, whatever slogans it might profess. He was suddenly an impotent alien, dependent on the bounty of a dictatorial state, and unable to return home. Out of one prison he had escaped into another. He was a pathetic ruin. The solace of his last years was a Russian wife much younger than himself, who nursed him and coddled him with great devotion. It was her firm hand which kept him from drink and imposed absolute rest and thus prolonged his life."

William Haywood was in poor health and died in the Soviet Union on 18th May, 1928. His autobiography, Bill Haywood's Book (1929) was published after his death.

Primary Sources

(1) Ramsay MacDonald, the future British prime minister, saw William Haywood make a speech on socialism in England when he was a young man.

William Haywood is the embodiment of the Sorel philosophy, roughened by the American industrial and civic climate, a bundle of primitive instincts, a master of direct statement. He is useless on committee; he is a torch amongst a crowd of uncritical and credulous workmen. I saw him at Copenhagen, amidst the leaders of the working-class movements drawn from the whole world, and there he was dumb and unnoticed; I saw him addressing a crowd in England, and there his crude appeals moved his listeners to wild applause. He made them see things, and their hearts bounded up to be up and doing.

(2) Louis Adamic, Dynamite: The Story of Class Violence in America (1934)

Bill Haywood was a he-man, a man of elemental force, with the physical strength of an ox, a big head and a tremendous jaw; hard, direct, immensely resistant, impatient of obstacles, careless, violent, ready and fit to deal blow for blow; a boozer; a son of the Rockies, risen, as he put it himself, "from the bowels of the earth," to grope his way through years of misery and economic injustice to Socialism.

(3) William Haywood, speech made at the convention where the Industrial Workers of the World was formed (27th June, 1905)

The American Federation of Labor, which presumes to be the labor movement of this country, is not a working-class movements. There are organizations that are affiliated with the American Federation of Labor which prohibit the initiation of a colored man; that prohibit the conferring of the obligation on foreigners. What we want to establish at this time is a labor organization that will open wide its doors to every man that earns his livelihood either by his brain or his muscle.

(4) Eugene Debs wrote about the arrest of William Haywood and Charles Moyer in Appeal to Reason (10th March, 1906)

There have been twenty years of revolutionary education, agitation, and organization since the Haymarket tragedy, and if an attempt is made to repeat it, there will be a revolution and I will do all in my power to precipitate it. If they attempt to murder Moyer, Haywood, and their brothers, a million revolutionists at least will meet them with guns.

(5) George Seldes, Witness to a Century (1987)

When Bill Hayward came to the coal and iron capital of America, Ray Springle and I went to his headquarters, not for news stories, which we knew would never be published, but out of interest in the new labor movement, the Industrial Workers of the World. And so, by chance along with its new leaders we met the ballad-maker of the IWW, Joe Hill.

(6) Statement issued by William Haywood and the Industrial Workers of the World about the First World War in 1915.

With the European war for conquest and exploitation raging and destroying the lives, class consciousness and unity of the workers, clouding the main issues, we openly declare ourselves the determined opponents of all nationalistic sectionalism, or patriotism, and the militarism preached and supported by our one enemy, the capitalist class. We condemn all wars, and for the prevention of such, we proclaim the anti-militarist propaganda in time of peace and, in time of war, the General Strike in all industries.

(7) William Haywood, speech made during his trial in 1917.

I am very much opposed to war, and would have the war stopped today if it were in my power to do it. I hope, if it be necessary, that every man that is imbued with the spirit of war will fight long enough to drive the spirit of hate and war out of his breast.

(8) Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia (1937)

One of the few Luxites who remained until the end uninhibited in his friendliness was Big Bill Haywood, former generalissimo of the I.W.W.'s. Unluckily his end came too soon. He died three months after we reached Moscow. In the broken, abnormally corpulent, homesick man with whom we played checkers at the Lux, there was scarcely a trace of the dynamic Haywood who had made labor history in America. A little of the old fire came into his one eye as we recalled episodes and mutual acquaintances in the I.W.W. movement. Then he relapsed into a tragic and hopeless boastfulness. The bust a Moscow sculptor was making of him, a diploma of some sort which he had been presented... He reached avidly for American cigarettes and waxed lyrical over the memory of American grub.

Though stupidly regarded by so many as "un-American," Haywood's every nerve and muscle was rooted in the American soil, and the movement which he started and led - a movement of hoboes, drifters, unskilled workers, lumberjacks and miners - was likewise authentically American in a sense that made it incomprehensible to foreign students. He had fled to Russia with other IWW men while out on bail and was therefore forever cut off from his native land. This robust, two-fisted American, essentially democratic and idealistic in his instincts, found the Bolshevik system of impersonal brutality hateful and fumed inwardly because he could say and do nothing about it. After a lifetime of fighting what he considered the delusions of political action, he could not swallow a super-state, whatever slogans it might profess. He was suddenly an impotent alien, dependent on the bounty of a dictatorial state, and unable to return home. Out of one prison he had escaped into another. He was a pathetic ruin.

The solace of his last years was a Russian wife much younger than himself, who nursed him and coddled him with great devotion. It was her firm hand which kept him from drink and imposed absolute rest and thus prolonged his life.

(9) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935)

My Communist visitors were even more dogmatic and at times no less irritating. It was easier to talk to American "Luxites" like Bill Haywood and a group of former members of the IWW who had been sentenced to long-term imprisonment in America during the anti-Red drive of 1919-20 and had "skipped" to Russia, as they termed it, when released bail pending an appeal against their conviction. They had little love for the land they had left behind them, but their political convictions were for the most part more negative than positive. As Big Bill once said to me, "The trouble with us old Wobblies is that we all know how to sock scabs and mine-guards and policemen or make tough fighting speeches to a crowd of strikers but we aren't so long on this ideological theory stuff as the Russians." I suggested that there might be another difficulty, that the Wobblies had been trying to destroy, like the Bolsheviks prior to October 1917, whereas the latter were now trying to build. Haywood replied shrewdly, "There's something in that but it goes far deeper. These Russians attach the hell of a lot to ideological theory, and mark my words, if they're not careful they'll come to blows about it one of these days. Don't you know yet that most of them would sooner talk than work, or even eat?"

Bill himself was out of place in Soviet Russia and his lion-hearted energy had begun to flag. He tried once to organise a group of American radicals for work in the Kusnetz iron basin in Western Siberia, but the venture was a failure. He stayed in Russia until his death six or seven years later, but I believe that he would have returned to America if he had been given the assurance that he would not have to spend the rest of his life in prison.

Another American radical, Bill Shatoff, was more fortunate. He was several years younger than Haywood and had the advantage of having been born in Russia and knowing the language. Shatoff is a big burly fellow and a real man-driver. He played an important part in repelling the Yudenich attack on Petrograd, then became in rapid succession a banker at Rostoff, director of an oil trust in the Caucasus, and head of a steel plant, all of course in the service of the State. After that he was put in charge of construction on the Turk-Sib Railway which he rushed to rapid conclusion. He has now a similar but much more extensive job on the new main line that is being built to connect Moscow with the Donetz coal-fields.