Murder of Frank Steunenberg

In 1899 Idaho was hit by a series of industrial disputes. The governor, Frank Steunenberg, took a tough line and declared martial law and asked President William McKinley to send federal troops to help him in his fight with the trade union movement. During the dispute over a thousand trade unionists and their supporters were rounded up and kept in stockades without trial.

The unions felt betrayed as they had mainly supported his campaign to become governor. Activists were particularly angry about Steunenberg's attempts to justify his actions: "We have taken the monster by the throat and we are going to choke the life out of it. No halfway measures will be adopted. It is a plain case of the state or the union winning, and we do not propose that the state shall be defeated."

Frank Steunenberg retired from office and on 30th December, 1905, he went out for a walk. On his return, when he pulled a wooden slide that opened the gate to his side door, it triggered a bomb, that killed him.

James McParland, from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was called in to investigate the murder. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire.

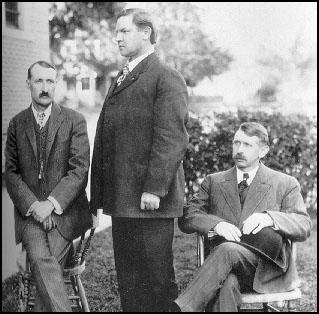

McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named William Hayward (general secretary of WFM) and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Charles Darrow, a man who specialized in defending trade union leaders, was employed to defend Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Harry Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry.

During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard. William Hayward, Charles Moyer and George Pettibone were all acquitted. Harry Orchard, because he had provided evidence against the other men, received life imprisonment rather than the death penalty. Orchard died in prison in 1954.

Primary Sources

(1) Harry Orchard, confession to James McParland (February, 1906)

I awoke, as it were, from a dream, and realized that I'd been made a tool of, aided and assisted by members of the Executive Board of the Western Federation of Miners. I resolved, as far as in my power, to break up this murderous organization and to protect the community from further assassinations and outrages from this gang.

(2) Oscar King Davis, The New York Times (6th June, 1907)

For three hours and a half today Harry Orchard sat in the witness chair at the Haywood trial and recited a history of crimes and bloodshed, the like of which no person in the crowded courtroom had ever imagined. Not in the whole range of "Bloody Gulch" literature will there be found anything that approaches a parallel to the horrible story so calmly and smoothly told by this self-possessed, imperturbable murderer witness.

Orchard in his first day on the stand told the details of these crimes. In 1906 he with another man placed a bomb in the Vindicator Mine at Cripple Creek, Colorado, that exploded and killed two men. Later he informed the officials of the Florence and Cripple Creek Railroad of a plot of the Western Federation to below up one of their trains, because he had not received money for work done for the federation. He watched the residence of Governor Peabody of Colorado and planned his assassination by shooting. This was postponed for reasons of policy. He shot and killed a deputy, Lyle Gregory, in Denver. He planned and with another man executed the blowing up of the railway station at the Independence Mine at Independence, Colorado which killed fourteen men. He tried to poison Fred Bradley, manager of the Sullivan and Bunk Hill mine, then living in San Francisco, by putting strychnine into his milk when it was left at his door in the morning. This failed, and in November, 1904, he arranged a bomb which blew Bradley into the street when he opened his door in the morning.

Orchard spoke in a soft, purring voice, marked by a slight Canadian accent, and except for the first few minutes that he was on the stand he went through his awful story as undisturbed as if he were giving the account of a May Day festival. When he said, "and then I shot him," his manner and tone were as matter-of-fact as if the words had been "and then I bought a drink."

There was nothing theatrical about the appearance on the stand of this witness, upon whose testimony the whole case against Haywood, Moyer, and the other leaders of the Western Federation of Miners is based. Only once or twice was there a dramatic touch. It was a horrible, revolting, sickening story, but he told it as simply as the plainest narration of the most ordinary incident of the most humdrum existence. He was neither a braggart nor a sycophant. He neither boasted of his fearful crimes nor sniveled in mock repentance.

Through all the story ran the names of the men for whom he worked and those who helped him in his wretched tasks. Haywood as the master. It was he who gave most of the orders. Pettibone, too, gave directions, furnished money, and once started out as if to help, but made excuse and turned back. That was in the Gregory murder. Haywood was the source of the money. Even what Pettibone gave him came from Haywood. Moyer he named occasionally, but not often. Moyer knew of some of the crimes, for he talked to Orchard about them and joined in Haywood's declaration that this or that "was a fine job."

But Haywood was the master, with Pettibone as the chief assistant, and then there were W. F. Davis, the old Coeur d'Alene comrade, and Sherman Parker and Charley Kennison of the district union, with W. B. Easterly Financial Secretary of Orchard's own union. Parker is dead now, shot a little while ago in Goldfield.

The defense professed to be pleased with the story as one that disproved itself. The prosecution, however, is sure it can be corroborated. Without question it produced a tremendous effect, and throughout its recital there ran a growing conviction of its truth.

(3) Charles Darrow, comments on Harry Orchard during the trial of Charles Moyer, William Hayward and George Pettibone (1907)

Gentlemen, I sometimes think I am dreaming in this case. I sometimes wonder whether this is a case, whether here in Idaho or anywhere in the country, broad and free, a man can be placed on trial and lawyers seriously ask to take away the life of a human being upon the testimony of Harry Orchard. We have the lawyers come here and ask you upon the word of that sort of a man to send this man to the gallows, to make his wife a widow, and his children orphans--on his word. For God's sake, what sort of an honesty exists up here in the state of Idaho that sane men should ask it? Need I come here from Chicago to defend the honor of your state? A juror who would take away the life of a human being upon testimony like that would place a stain upon the state of his nativity--a stain that all the waters of the great seas could never wash away. And yet they ask it. You had better let a thousand men go unwhipped of justice, you had better let all the criminals that come to Idaho escape scot free than to have it said that twelve men of Idaho would take away the life of a human being upon testimony like that.

Why, gentlemen, if Harry Orchard were George Washington who had come into a court of justice with his great name behind him, and if he was impeached and contradicted by as many as Harry Orchard has been, George Washington would go out of it disgraced and counted the Ananias of the age.

I am sorry to say it, but it is true, because religious men have killed now and then, they have lied now and then. . . . Of all the miserable claptrap that has been thrown into a jury for the sake of getting it to give some excuse for taking the life of a man, this is the worst. Orchard saves his soul by throwing the burden on Jesus, and he saves his life by dumping it onto Moyer, Haywood and Pettibone. And you twelve men are asked to set your seal of approval on it.

I don't believe that this man Orchard was ever really in the employ of anybody. I don't believe he ever had any allegiance to the Mine Owners Association, to the Pinkertons, to the Western Federation of Miners, to his family, to his kindred, to his God, or to anything human or divine. I don't believe he bears any relation to anything that a mysterious and inscrutable Providence has ever created. He was a soldier of fortune, ready to pick up a penny or a dollar or any other sum in any way that was easy to serve the mine owners, to serve the Western Federation, to serve the devil if he got his price, and his price was cheap.

(4) Charles Darrow, comments on Trade Unions during the trial of Charles Moyer, William Hayward and George Pettibone (1907)

Let me tell you, gentlemen, if you destroy the labor unions in this country, you destroy liberty when you strike the blow, and you would leave the poor bound and shackled and helpless to do the bidding of the rich. It would take this country back to the time when there were masters and slaves.

I don't mean to tell this jury that labor organizations do no wrong. I know them too well for that. They do wrong often, and sometimes brutally; they are sometimes cruel; they are often unjust; they are frequently corrupt. But I am here to say that in a great cause these labor organizations, despised and weak and outlawed as they generally are, have stood for the poor, they have stood for the weak, they have stood for every human law that was ever placed upon the statute books. They stood for human life, they stood for the father who was bound down by his task, they stood for the wife, threatened to be taken from the home to work by his side, and they have stood for the little child who was also taken to work in their places - that the rich could grow richer still, and they have fought for the right of the little one, to give him a little of life, a little comfort while he is young. I don't care how many wrongs they committed, I don't care how many crimes these weak, rough, rugged, unlettered men who often know no other power but the brute force of their strong right arm, who find themselves bound and confined and impaired whichever way they turn, who look up and worship the god of might as the only god that they know - I don't care how often they fail, how many brutalities they are guilty of. I know their cause is just.

I hope that the trouble and the strife and the contention has been endured. Through brutality and bloodshed and crime has come the progress of the human race. I know they may be wrong in this battle or that, but in the great, long struggle they are right and they are eternally right, and that they are working for the poor and the weak. They are working to give more liberty to the man, and I want to say to you, gentlemen of the jury, you Idaho farmers removed from the trade unions, removed from the men who work in industrial affairs, I want to say that if it had not been for the trade unions of the world, for the trade unions of England, for the trade unions of Europe, the trade unions of America, you today would be serfs of Europe, instead of free men sitting upon a jury to try one of your peers. The cause of these men is right.

(5) Charles Darrow, comments on the possible conviction and execution of William Hayward (1907)

He (William Hayward) has fought many a fight, many a fight with the persecutors who are hounding him into this court. He has met them in many a battle in the open field, and he is not a coward. If he is to die, he will die as he has lived, with his face to the foe.

To kill him, gentlemen? I want to speak to you plainly. Mr. Haywood is not my greatest concern. Other men have died before him, other men have been martyrs to a holy cause since the world began. Wherever men have looked upward and onward, forgotten their selfishness, struggled for humanity, worked for the poor and the weak, they have been sacrificed. They have been sacrificed in the prison, on the scaffold, in the flame. They have met their death, and he can meet his if you twelve men say he must.

Gentlemen, you short-sighted men of the prosecution, you men of the Mine Owners' Association, you people who would cure hatred with hate, you who think you can crush out the feelings and the hopes and the aspirations of men by tying a noose around his neck, you who are seeking to kill him not because it is Haywood but because he represents a class, don't be so blind, don't be so foolish as to believe you can strangle the Western Federation of Miners when you tie a rope around his neck. Don't be so blind in your madness as to believe that if you make three fresh new graves you will kill the labor movement of the world. I want to say to you, gentlemen, Bill Haywood can't die unless you kill him. You have got to tie the rope. You twelve men of Idaho, the burden will be on you. If at the behest of this mob you should kill Bill Haywood, he is mortal. He will die. But I want to say that a hundred will grab up the banner of labor at the open grave where Haywood lays it down, and in spite of prisons, or scaffolds, or fire, in spite of prosecution or jury, these men of willing hands will carry it on to victory in the end.

(6) James Hawley, prosecuting attorney, speech to the jury (1907)

I remembered again the awful thing of December 30, 1905, a night which has taken ten years to the life of some who are in this courtroom now. I felt again its cold and icy chill, faced the drifting snow and peered at last into the darkness for the sacred spot where last lay the body of my dead friend, and saw true, only too true, the stain of his life's blood upon the whitened earth. I saw Idaho dishonored and disgraced. I saw murder--no, not murder, a thousand times worse than murder - I saw anarchy wave its first bloody triumph in Idaho. And as I thought again I said, ‘Thou living God, can the talents or the arts of counsel unteach the lessons of that hour?' No, no. Let us be brave, let us be faithful in this supreme test of trial and duty. If the defendant is entitled to his liberty, let him have it. But, on the other hand, if the evidence in this case discloses the author of this crime, then there is no higher duty to be imposed upon citizens than the faithful discharge of that particular duty. Some of you men have stood the test and trial in the protection of the American flag. But you never had a duty imposed upon you which required more intelligence, more manhood, more courage than that which the people of Idaho assign to you this night in the final discharge of your duty.