Pinkerton Detective Agency

Allan Pinkerton, a deputy-sheriff in Chicago, formed the Pinkerton Detective Agency in 1852. The first detective agency in the United States, it solved a series of train robberies. In 1861 the agency was given the task of guarding Abraham Lincoln. While in Baltimore, while on the way to the inauguration, Pinkerton foiled a plot to assassinate the president.

Pinkerton became head of the American secret service during the Civil War and in 1875 used an agent, James McParland, to infiltrate the secret organization, the Molly Maguires. McParlan's evidence in court resulted in the execution of twenty of its members.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency was a great success. On the facade of his three-story Chicago headquarters was the company slogan, "We Never Sleep". Above this was a huge, black and white eye. The Pinkerton logo was the origin of the term private eye.

In 1873 Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, had a meeting with Allan Pinkerton of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Gowen had considerable investments in the coal-mines of Schuylkill County and feared that the trade union activities of John Siney and the Workingmen's Benevolent Association would result in lower profits.

Allan Pinkerton decided to send James McParland to Schuylkill County. Assuming the alias of James McKenna, he found work as a labourer in Shenandoah. Soon afterwards he joined the Workingmen's Benevolent Association and the Shenandoah branch of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), an organisation for Irish immigrants run by the Roman Catholic clergy.

After a few months of investigations McParland reported back to Allan Pinkerton that some members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians were also active in the secret organization, the Molly Maguires. McParland estimated that the group had about 3,000 members. Each county was governed by a bodymaster who recruited members and gave out orders to commit crimes. These bodymasters were usually ex-miners who now worked as saloon keepers.

Over a two year period James McParland collected evidence about the criminal activities of the Molly Maguires. This included the murder of around fifty men in Schuylkill County. Many of these men were the managers of coal mines in the region.

John Kehoe, one of the leaders of the Molly Maguires became suspicious of McParland and began to investigate his past. McParland was tipped off that Kehoe was planning to murder him so he fled from the area.

In 1876 and 1877 James McParland was the star witness for the prosecution of John Kehoe and the Molly Maguires. Twenty members were found guilty of murder and were executed. This included Kehoe, a former union leader who was convicted of a murder that had taken place fourteen years previously.

After Allan Pinkerton died in 1884, the Pinkerton Detective Agency was run by his two sons, Robert Pinkerton and William Pinkerton. The brothers opened their fourth office in Denver. They appointed James McParland and Charlie Siringo to run the Pinkerton's western division.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency often supplied men to break strikes. In 1892 the Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers Union called out its members at the Homestead plant owned by Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick. The men were brought in on armed barges down the Monongahela River. The strikers were waiting for them and a day long battle took place. Seven Pinkerton agents and nine workers were killed and created a great deal of bad publicity for the agency.

In 1906 James McParland was called in to investigate the murder of Frank Steunenberg, the governor of Idaho. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire.

McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named William Hayward (general secretary of WFM) and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Charles Darrow, a man who specialized in defending trade union leaders, was employed to defend Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry.

During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard. William Hayward, Charles Moyer and George Pettibone were all acquitted. Orchard, because he had provided evidence against the other men, received life imprisonment rather than the death penalty.

In 1912 Charlie Siringo published a book, A Cowboy Detective: A True Story of Twenty-Two Years With A World-Famous Detective Agency, where he claimed that James McParland had ordering him to commit voter fraud in the re-election attempt of Colorado Governor James Peabody. This view is supported by historian Mary Joy Martin who argued in The Corpse On Boomerang Road (2004): "McParland would stop at nothing to take down (unions such as the Western Federation of Miners) because he believed his authority came from "Divine Providence." To carry out God's Will meant he was free to break laws and lie until every man he judged evil was hanging on the gallows. Since his days in Pennsylvania he was comfortable lying under oath. In the Haywood trial and the Adams trials, he lied frequently, even claiming he never joined the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Documents showed he had."

Charlie Siringo, who had worked for more than twenty years under James McParland in the Pinkerton's western division based in Denver, claimed that the agency had been guilty of "jury tampering, fabricated confessions, false witnesses, bribery, intimidation, and hiring killers for its clients... Documents and time sustained many of his assertions."

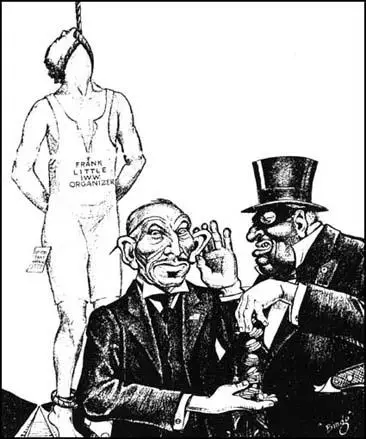

In the summer of 1917, Frank Little was helping organize workers in the metal mines of Montana. This included leading a strike of miners working for the Anaconda Company. In the early hours of 1st August, 1917, six masked men broke into Little's hotel room in Butte. He was beaten up, tied by the rope to a car, and dragged out of town, where he was lynched. A note: "First and last warning" was pinned to his chest. No serious attempt was made by the police to catch Little's murderers. It is not known if he was killed for his anti-war views or his trade union activities.

them he was a traitor." Solidarity (11th August, 1917)

The lawyer representing the Anaconda Company said a few days later: "These Wobblies, snarling their blasphemies in filthy and profane language; they advocate disobedience of the law, insults to our flag, disregard of all property rights and destruction of the principles and institutions which are the safeguards of society.... Why, Little, the man who was hanged in Butte, prefaced his seditious and treasonable speeches with the remark that he expected to be arrested for what he was going to say... The Wobblies... have invariably shown themselves to be bullies, anarchists and terrorists. These things they do openly and boldly."

Lillian Hellman claimed in Scoundrel Time (1976) that Dashiell Hammett, while working for the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Montana, turned down an offer of $5,000 to "do away with" Frank Little. Hellman recalled: "Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer (to kill Frank Little) so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder, and the fact that Frank Little was lynched with three other men in what was known as the Everett Massacre must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I think I can date Hammett's belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little's murder."

Primary Sources

(1) Franklin B. Gowen, speech during the trial of the Molly Maguires (1876)

Is there a man in this audience, looking at me now, and hearing me denounce this association, who longs to point his pistol at me ? I tell him that he has as good chance here as he will ever have again. I tell him that if there is another murder in this county, committed by this organization, every one of the five hundred members of the order in this county or out of it. who connives at it, will be guilty of murder in the first degree, and can be hanged by the neck until he is dead. I tell him that if there is another murder in this county by this society, there will be an inquisition for blood with which nothing that has been known in the annals of criminal jurist prudence can compare.

And to whom are we indebted for this security, of which I now boast? To whom do we owe all this? Under the divine providence of God, to whom be all the honor and all the glory, we owe this safety to James McParland; and if there ever was a man to whom the people of this county should erect a monument, it is James McParland the detective. It is simply a question between the Molly Maguires on the one side, and Pinkerton's Detective Agency on the other; and I know too well that Pinkerton's Detective Agency will win. There is not a place on the habitable globe where these men can find refuge and in which they will not be tracked down.

(2) Cleveland Moffett, McClure's Magazine (1894)

The origin and development of the Molly Maguires will always present a hard problem to the social philosopher, who will, perhaps, find some subtle relation between crime and coal. One understands the act of an ordinary murderer who kills from greed, or fear, or hatred; but the Molly Maguires killed men and women with whom they had had no dealings, against whom they had no personal grievances, and from whose death they had nothing to gain, except, perhaps, the price of a few rounds of whiskey. They committed murders by the score, stupidly, brutally, as a driven ox turns to left or right at the word of command, without knowing why, and without caring. The men who decreed these monstrous crimes did so for the most trivial reasons—a reduction in wages, a personal dislike, some imagined grievance of a friend. These were sufficient to call forth an order to burn a house where women and children were sleeping, to shoot down in cold blood an employer or fellow workman, to lie in wait for an officer of the law and club him to death. In the trial of one of them, Mr. Franklin B. Gowen described the reign of these ready murderers as a time "when men retired to their homes at eight or nine o'clock in the evening and no one ventured beyond the precincts of his own door; when every man engaged in any enterprise of magnitude, or connected with industrial pursuits' left his home in the morning with his hand upon his pistol, unknowing whether he would again return alive; when the very foundations of society were being overturned."

(3) Mary Joy Martin, The Corpse On Boomerang Road (2004)

McParland would stop at nothing to take down (unions such as the Western Federation of Miners) because he believed his authority came from "Divine Providence." To carry out God's Will meant he was free to break laws and lie until every man he judged evil was hanging on the gallows. Since his days in Pennsylvania he was comfortable lying under oath. In the Haywood trial and the Adams trials, he lied frequently, even claiming he never joined the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Documents showed he had.

(4) Lillian Hellman, Scoundrel Time (1976)

Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer (to kill Frank Little) so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder, and the fact that Frank Little was lynched with three other men in what was known as the Everett Massacre must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I think I can date Hammett's belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little's murder.

(5) Diane Johnson, The Life of Dashiell Hammett (1984)

It was in a boardinghouse in Butte, Montana, in 1917 that the owner, Mrs. Nora Byrne, was awakened one night by voices in the room next to hers, room 30, men's voices saying there must he some mistake here, and then feet in the hall, then men at her door, pushing it open, and Mrs. Byrne, having jumped out of bed, held her door with all her strength as some men with guns pushed it in anyway. They held the gun on her, saying, "Where is Frank Little?" and she told them. Then they went away again, and kicked down the door of room 32 and went in and woke the man sleeping there, who made no outcry or objection and demanded no explanation. Because he had a broken leg, they had to carry him out.

Then, in the morning, he was found hanging from the trestle with a warning to others pinned to his underwear. Some people said his balls had been cut off. The warning came from the Montana vigilantes, though it was hard to see what the citizens of Montana stood to gain from the death of this poor man. Only the mine owners stood to gain from the death of this agitator, a Wobbly. Wobblies were stirring up a lot of trouble among the miners at Butte.

"These Wobblies," said the mine owner's lawyer a few days later, "snarling their blasphemies in filthy and profane language; they advocate disobedience of the law, insults to our flag, disregard of all property rights and destruction of the principles and institutions which are the safeguards of society." He was trying to show that Mr. Little had brought his lynching on himself. "Why, Little, the man who was hanged in Butte, prefaced his seditious and treasonable speeches with the remark that he expected to be arrested for what he was going to say." Perhaps he had not expected, however, to he hanged, but what were decent Americans to do with such rascals?

The mine owner's lawyer, noticing no contradiction, inconsistency or irony, proclaimed that the Wobblies "have invariably shown themselves to be bullies, anarchists and terrorists. These things they do openly and boldly," unlike (he did not add) all the decent American vigilantes who came masked by night. The young Hammett, in Montana at the time, noticed the ironies and inconsistencies with particular interest because men had come to him and to other Pinkerton agents and had proposed that they help do away with Frank Little. There was a bonus in it, they told him, of $5,000, an enormous sum in those days.

Hammett's inclinations had probably always been on the side of law and order. His father had once been a justice of the peace and always went to the law when necessary with confidence, for instance, when his buggy was damaged by the potholes on the public road; and he worked for a lock-and-safe company, and at other times as a watchman or a guard. There was thus in the family a brief for caring about the property of others, putting oneself at risk so that things in general should be safe and secure.

But at some moment - perhaps at the moment he was asked to murder Frank Little or perhaps at the moment that he learned that Little had been killed, possibly by other Pinkerton men - Hammett saw that the actions of the guards and the guarded, of the detective and the man he's stalking, are reflexes of a single sensibility, on the fringe where murderers and thieves live. He saw that he himself was on the fringe or might be, in his present line of work, and was expected to be, according to a kind of oath of fealty that he and other Pinkerton men took.

He also learned something about the lives of poor miners, whose wretched strikes the Pinkerton people were hired to prevent, and about the lies of mine owners. These things were to sit in the back of his mind.

And just as he learned about the lot of poor miners, and about the aims of trade unions, so at some point he learned about the rich. He saw their houses - maybe as a Pinkerton man, or maybe it was back in Baltimore that he noticed the furniture and pictures in rich people's houses, different from the crowded parlor on North Stricker Street, or from the boardinghouses and cheap hotels he stayed in.