Frank Little

Frank Little was born in 1879. Little is known about his family background but he told friends that he had "Indian blood". However, Sal Salerno argues that he had a Cherokee Indian mother and Quaker father.

Little joined the Industrial Workers of the World in 1906 and took part in the free speech campaigns in Missoula, Fresno and Spokane and was involved in organizing lumberjacks, metal miners and oil field workers into trade unions. On one occasion he was sentenced to 30 days imprisonment for reading the Declaration of Independence on a street corner.

Other members of the IWW included: William Haywood, Vincent Saint John, Daniel De Leon, Eugene V. Debs, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Lucy Parsons, Hubert Harrison, Carlo Tresca, Joseph Ettor, Arturo Giovannitti, James Cannon, William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, Joe Haaglund Hill, Tom Mooney, Floyd B. Olson, James Larkin, James Connolly, Frank Little and Ralph Chaplin.

In 1910 Little successfully organized unskilled fruit workers in the San Joaquin Valley. Sal Salerno has argued that he was a "fearless and uncompromising agitator, he was repeatedly beaten and jailed for his union-forming activities." This brought him to the attention of the national leadership of the Industrial Workers of the World and by 1916 was a member of the party's General Executive Board.

Little was a strong opponent of the USA becoming involved in the First World War. The leader of the party, William Haywood shared Little's opinions, but this was a minority view in the party. When the USA joined the war in April, 1917, Ralph Chaplin, the editor of the trade union journal, Solidarity, claimed that opposing the draft would destroy the IWW. Little refused to back down on this issue and argued that: "the IWW is opposed to all wars, and we must use all our power to prevent the workers from joining the army."

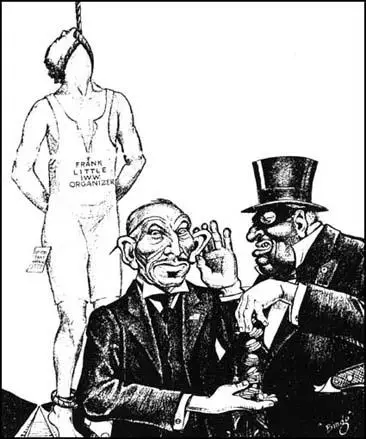

In the summer of 1917, Little was helping organize workers in the metal mines of Montana. This included leading a strike of miners working for the Anaconda Company. In the early hours of 1st August, 1917, six masked men broke into Little's hotel room in Butte. He was beaten up, tied by the rope to a car, and dragged out of town, where he was lynched. A note: "First and last warning" was pinned to his chest. No serious attempt was made by the police to catch Little's murderers. It is not known if he was killed for his anti-war views or his trade union activities.

them he was a traitor." Solidarity (11th August, 1917)

The lawyer representing the Anaconda Company said a few days later: "These Wobblies, snarling their blasphemies in filthy and profane language; they advocate disobedience of the law, insults to our flag, disregard of all property rights and destruction of the principles and institutions which are the safeguards of society.... Why, Little, the man who was hanged in Butte, prefaced his seditious and treasonable speeches with the remark that he expected to be arrested for what he was going to say... The Wobblies... have invariably shown themselves to be bullies, anarchists and terrorists. These things they do openly and boldly."

Lillian Hellman claimed in Scoundrel Time (1976) that Dashiell Hammett, while working for the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Montana, turned down an offer of $5,000 to "do away with" Frank Little. Hellman recalled: "Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer (to kill Frank Little) so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder, and the fact that Frank Little was lynched with three other men in what was known as the Everett Massacre must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I think I can date Hammett's belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little's murder."

Primary Sources

(1) The Appeal to Reason journal reported on attempts by Frank Little to recruit members for the Industrial Workers of the World in California (11th February, 1911)

There are about one hundred I.W.W. men in jail now with different charges, but all are arrested for the same offense. Only a few of the I.W.W. men have been tried. Some of the best speakers were tried and convicted of vagrancy, by juries of business men. Four of them got six months apiece, although they proved that they were not vagrants. Many of the boys have been imprisoned for fifty-one days, today, without trial. This happened not in Russia, but in sunny California. Frank Little was arrested on the charge of vagrancy.

Frank Little was arrested on the charge of vagrancy. Frank is one of the 94 I.W.W. men confined in a bull pen, 47 x 28 feet. The officers of the state board of health say that there is air enough in the pen for 5 men. Most of the men confined in the bull pen have been out in the open air only once or twice since they were arrested. A good many of the men have been in there 53 days today.

(2) Helen Keller, The Liberator (1918)

On August 1st, of 1917, in Butte, Montana, a cripple, Frank Little, a member of the Executive Board of the IWW, was forced out of bed at three o’clock in the morning by masked citizens, dragged behind an automobile and hanged on a railroad trestle. Were the offenders punished? No. A high government official has publicly condoned this murder, thereby upholding lynch-law and mob rule.

(3) Viola Gilbert Snell, To Frank Little ( 25th August, 1917)

Traitor and demagogue,

Wanton breeder of discontent -

That is what they call you -

Those cowards, who condemn sabotage

But hide themselves

Not only behind masks and cloaks

But behind all the armoured positions

Of property and prejudice and the law.

Staunch friend and comrade,

Soldier of solidarity -

Like some bitter magic

The tale of your tragic death

Has spread throughout the land,

And from a thousand minds

Has torn the last shreds of doubt

Concerning Might and Right.

Young and virile and strong -

Like grim sentinels they stand

Awaiting each opportunity

To break another

Of slavery's chains.

For whatever stroke is needed.

They are preparing.

So shall you be avenged.

(4) Arthuro Giovannitti, Hanged at Midnight (2nd September, 1917)

Six men drove up to his house at midnight, and woke the poor woman who kept it,

And asked her: "Where is the man who spoke against war and insulted the army?"

And the old woman took fear of the men and the hour, and showed them the room where he slept,

And when they made sure it was he whom they wanted, they dragged him from his bed with blows, tho' he was willing to walk,

And they fastened his hands on his back, and they drove him across the black night,

And there was no moon and no star and not any visible thing, and even the faces of the men were eaten with the leprosy of the dark, for they were masked with black shame,

And nothing showed in the gloom save the glow of his eyes and the flame of his soul that scorched the face of Death.

(5) Lillian Hellman, Scoundrel Time (1976)

Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer (to kill Frank Little) so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder, and the fact that Frank Little was lynched with three other men in what was known as the Everett Massacre must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I think I can date Hammett's belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little's murder.

(6) Diane Johnson, The Life of Dashiell Hammett (1984)

It was in a boardinghouse in Butte, Montana, in 1917 that the owner, Mrs. Nora Byrne, was awakened one night by voices in the room next to hers, room 30, men's voices saying there must he some mistake here, and then feet in the hall, then men at her door, pushing it open, and Mrs. Byrne, having jumped out of bed, held her door with all her strength as some men with guns pushed it in anyway. They held the gun on her, saying, "Where is Frank Little?" and she told them. Then they went away again, and kicked down the door of room 32 and went in and woke the man sleeping there, who made no outcry or objection and demanded no explanation. Because he had a broken leg, they had to carry him out.

Then, in the morning, he was found hanging from the trestle with a warning to others pinned to his underwear. Some people said his balls had been cut off. The warning came from the Montana vigilantes, though it was hard to see what the citizens of Montana stood to gain from the death of this poor man. Only the mine owners stood to gain from the death of this agitator, a Wobbly. Wobblies were stirring up a lot of trouble among the miners at Butte.

"These Wobblies," said the mine owner's lawyer a few days later, "snarling their blasphemies in filthy and profane language; they advocate disobedience of the law, insults to our flag, disregard of all property rights and destruction of the principles and institutions which are the safeguards of society." He was trying to show that Mr. Little had brought his lynching on himself. "Why, Little, the man who was hanged in Butte, prefaced his seditious and treasonable speeches with the remark that he expected to be arrested for what he was going to say." Perhaps he had not expected, however, to he hanged, but what were decent Americans to do with such rascals?

The mine owner's lawyer, noticing no contradiction, inconsistency or irony, proclaimed that the Wobblies "have invariably shown themselves to be bullies, anarchists and terrorists. These things they do openly and boldly," unlike (he did not add) all the decent American vigilantes who came masked by night. The young Hammett, in Montana at the time, noticed the ironies and inconsistencies with particular interest because men had come to him and to other Pinkerton agents and had proposed that they help do away with Frank Little. There was a bonus in it, they told him, of $5,000, an enormous sum in those days.

Hammett's inclinations had probably always been on the side of law and order. His father had once been a justice of the peace and always went to the law when necessary with confidence, for instance, when his buggy was damaged by the potholes on the public road; and he worked for a lock-and-safe company, and at other times as a watchman or a guard. There was thus in the family a brief for caring about the property of others, putting oneself at risk so that things in general should be safe and secure.

But at some moment - perhaps at the moment he was asked to murder Frank Little or perhaps at the moment that he learned that Little had been killed, possibly by other Pinkerton men - Hammett saw that the actions of the guards and the guarded, of the detective and the man he's stalking, are reflexes of a single sensibility, on the fringe where murderers and thieves live. He saw that he himself was on the fringe or might be, in his present line of work, and was expected to be, according to a kind of oath of fealty that he and other Pinkerton men took.

He also learned something about the lives of poor miners, whose wretched strikes the Pinkerton people were hired to prevent, and about the lies of mine owners. These things were to sit in the back of his mind.

And just as he learned about the lot of poor miners, and about the aims of trade unions, so at some point he learned about the rich. He saw their houses - maybe as a Pinkerton man, or maybe it was back in Baltimore that he noticed the furniture and pictures in rich people's houses, different from the crowded parlor on North Stricker Street, or from the boardinghouses and cheap hotels he stayed in.