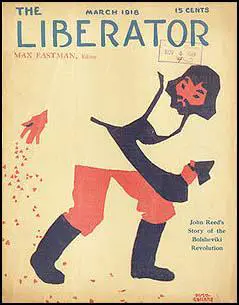

The Liberator

During the the First World War, most of the people who worked for the believed that the USA should remain neutral. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the The Masses magazine came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges.

In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that articles by Floyd Dell and Max Eastman and cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and H. J. Glintenkamp had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication.

In 1918 the same people who produced The Masses, including the editor, Max Eastman, went on the publish a very similar journal, The Liberator. The journal published information about socialist movements throughout the world and was the first to break the news that the Allies had invaded Russia.

The author of A Dreamer's Paradise Lost (1995) pointed out that Floyd Dell continued to have an important influence on The Liberator: "Floyd Dell's spirited literary columns continued to highlight figures like Sherwood Anderson, to uphold the sheer beauty of poetry, and to engage in an eclectic variety of literary proposals."

People who contributed to the journal included Crystal Eastman, Art Young, Claude McKay, Boardman Robinson, Roger Baldwin, Michael Gold, Josephine Herbst, Lucy Parsons, Louis Fraina, Norman Thomas, John Reed, Louise Bryant, Bertrand Russell, Dorothy Day, Robert Minor, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, Maurice Becker, Helen Keller, Cornelia Barns, Louis Untermeyer, Hugo Gellert, K. R. Chamberlain and William Gropper.

In 1920 Michael Gold was appointed editor of The Liberator. Two years later the the journal was taken over by Robert Minor and the Communist Party and in 1924 was renamed as The Workers' Monthly. Many of the people who contributed to the The Masses and the original Liberator, were unhappy with this development and in 1926, they started their own journal, the New Masses.

Primary Sources

(1) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

The Masses harassed by the post-office authorities, was suppressed in October, 1917, by the Government, and its editors were indicted, myself among them, under the so-called Espionage Act, which was being used not against German spies but against American Socialists, Pacifists, and anti-war radicals. Sentences of twenty years were being served out to all who dared say this was not a war to end war, or that the Allied loans would never be paid. But the courts would probably not get around to us until next year; and we immediately made plans to start another magazine, The Liberator, and tell more truth; we would stand on the pre-war Wilsonian program, and call for a negotiated peace.

(2) The Liberator, editorial, introductory issue (March 1918)

Never was the moment more auspicious to issue a great magazine of liberty. With the Russian people in the lead, the world is entering upon the experiment of industrial and real democracy. Inspired by Russia, the German people are muttering a revolt that will go farther than its dearest advocates among the Allies dream. The working people of France, of Italy, of England, too, are determined that the end of autocracy in Germany shall be the end of wage-slavery at home. America has extended her hand to the Russians. She will follow in their path. The world is in the rapids. The possibilities of change in this day are beyond all imagination. We must unite our hands and voices to make the end of this war the beginning of an age of freedom and happiness for mankind undreamed by those whose 'minds comprehend only political and military events. With this ideal The Liberator comes into being on Lincoln's Birthday February 12, 1918.

The Liberator will be owned and published by its editors, who will be free in its pages to say what they truly think. It will fight in the struggle of labor. It will fight for the ownership and control of industry by the workers, and will present vivid and accurate news of the labor and socialist movements in all parts of the world.

It will advocate the opening of the land to the people, and urge the immediate taking over by the people of railroads, mines, telegraph and telephone systems, and all public utilities.

It will stand for the complete independence of women - politi- cal, social and economic - and an enrichment of the existence of mankind.

It will stand for a revolution in the whole spirit and method of dealing with crime.

It will join all wise men in trying to substitute for our rigid scholastic kind of educational system one which has a vivid relation to life.

It will assert the social and political equality of the black and white races, oppose every kind of racial discrimination, and conduct a remorseless publicity campaign against lynch law.

It will oppose laws preventing the spread of scientific knowledge about birth control.

The Liberator will endorse the war aims outlined by the Russian people and expounded by President Wilson - a peace without forcible annexations, without punitive indemnities, with free development and self-determination for all peoples. Especially it will support the President in his demand for an international union, based upon free seas, free commerce and general disarmament, as the central principle upon which hang all hopes for permanent peace and friendship among nations.

The Liberator will be distinguished by complete freedom in art and poetry and fiction and criticism. It will be candid. It will be experimental. It will be hospitable to new thoughts and feelings. It will direct its attacks against dogma and rigidity of mind upon whichever side they are found.

(3) Helen Keller, The Liberator (1918)

Down through the long, weary years the will of the ruling class has been to suppress either the man or his message when they antagonized its interests. From the execution of the propagandist and the burning of books, down through the various degrees of censorship and expurgation to the highly civilized legal indictment and winking at mob crime by constituted authorities, the cry has ever been “crucify him!” The ideas and activities of minorities are misunderstood and misrepresented. It is easier to condemn than to investigate. It takes courage to steer one’s course through a storm of abuse and ignominy. But I believe that discussion of even the most bitterly controverted matters is demanded by our love of justice, by our sense of fairness and an honest desire to understand the problems that are rending society. Let us review the facts relating to the situation of the IWWs since the United States of America entered the war with the declared purpose to conserve the liberties of the free peoples of the world.

During the last few months, in Washington State, at Pasco and throughout the Yakima Valley, many “IWW” members have been arrested without warrants, thrown into “bull-pens” without access to attorney, denied bail and trial by jury, and some of them shot. Did any of the leading newspapers denounce these acts as unlawful, cruel, undemocratic? No. On the contrary, most of them indirectly praised the perpetrators of these crimes for their patriotic service!

On August 1st, of 1917, in Butte, Montana, a cripple, Frank Little, a member of the Executive Board of the IWW, was forced out of bed at three o’clock in the morning by masked citizens, dragged behind an automobile and hanged on a railroad trestle. Were the offenders punished? No. A high government official has publicly condoned this murder, thereby upholding lynch-law and mob rule.

On the 12th of last July [1917], 1200 miners were deported from Bisbee, Arizona, without legal process. Among them were many who were not IWWs or even in sympathy with them. They were all packed into freight cars like cattle and flung upon the desert of New Mexico, where they would have died of thirst and hunger if an outraged society had not protested. President Wilson telegraphed the Governor of Arizona that it was a bad thing to do, and a commission was sent to investigate. But nothing has been done. No measures have been taken to return the miners to their homes and families.

Last September the 5th, an army of officials raided every hall and office of the IWW from Maine to California. They rounded up 166 IWW officers, members and sympathizers, and now they are in jail in Chicago, awaiting trial on the general charge of conspiracy.

In a short time these men will be tried in a Chicago court. The newspapers will be full of stupid, if not malicious comments on their trial. Let us keep an open mind. Let us try to preserve the integrity of our judgment against the misrepresentation, ignorance and cowardice of the day. Let us refuse to yield to conventional lies and censure. Let us keep our hearts tender towards those who are struggling mightily against the greatest evils of the age. Who is truly indicted, they or the social system that has produced them? A society that permits the conditions out of which the IWWs have sprung, stands self-condemned.

The IWW is pitted against the whole profit-making system. It insists that there can be no compromise so long as the majority of the working class live in want, while the master class lives in luxury. According to its statement, “there can be no peace until the workers organize as a class, take possession of the resources of the earth and the machinery of production and distribution, and abolish the wage-system.” In other words, the workers in their collectivity must own and operate all the essential industrial institutions and secure to each laborer the full value of his produce. I think it is for this declaration of democratic purpose, and not for any wish to betray their country, that the IWW members are being persecuted, beaten, imprisoned and murdered.

Surely the demands of the IWW are just. It is right that the creators of wealth should own what they create. When shall we learn that we are related one to the other; that we are members of one body; that injury to one is injury to all? Until the spirit of love for our fellow-workers, regardless of race, color, creed or sex, shall fill the world, until the great mass of the people shall be filled with a sense of responsibility for each other’s welfare, social justice cannot be attained, and there can never be lasting peace upon earth.

I know those men are hungry for more life, more opportunity. They are tired of the hollow mockery of mere existence in a world of plenty. I am glad of every effort that the working men make to organize. I realize that all things will never be better until they are organized, until they stand all together like one man. That is my one hope of world democracy. Despite their errors, their blunders and the ignominy heaped upon them, I sympathize with the IWWs. Their cause is my cause. While they are threatened and imprisoned, I am manacled. If they are denied a living wage, I, too, am defrauded. While they are industrial slaves, I cannot be free. My hunger is not satisfied while they are unfed. I cannot enjoy the good things of life that come to me while they are hindered and neglected.

The mighty mass-movement of which they are a part is discernible all over the world. Under the fire of the great guns, the workers of all lands, becoming conscious of their class, are preparing to take possession of their own.

That long struggle in which they have successively won freedom of body from slavery and serfdom, freedom of mind from ecclesiastical despotism, and more recently a voice in government, has arrived at a new stage. The workers are still far from being in possession of themselves or their labor. They do not own and control the tools and materials which they must use in order to live, nor do they receive anything like the full value of what they produce. Workingmen everywhere are becoming aware that they are being exploited for the benefit of others, and that they cannot be truly free unless they own themselves and their labor. The achievement of such economic freedom stands in prospect - and at no distant date- as the revolutionary climax of the age.

(4) Crystal Eastman, The Liberator (February 1919)

Some good friends of the Liberator are disturbed at our want of enthusiasm for the League of Nations. We believe in a League of Nations as the one thing that will ever remove the menace of nationalistic war from the earth. We believe that it must be a definite, concrete, continuous and working federation of the peoples. We believe that such a thing may come to pass in the near future, and we will work for it. But we do not discover in the victorious governments that are meeting in Paris, nor in any of the delegates of these governments, the least disposition to establish such a federation of the peoples. We are not free to say all that we might of these governments, but we can say that the hands they clasp over the council table will be red with the fresh blood of the freest people on earth.

(5) Crystal Eastman, The Liberator (February 1919)

Bela Kun is a young man (they are all young) - probably 29 or 30. He is stocky and powerful in physical build, not very tall, with a big bulging bullet-head shaved close. His wide face with small eyes, heavy jaws and thick lips is startling when you first see it close - I am told it is a well-known Magyar type—but his smile is sunny and winning, and he looks resolute and powerful. He has a superhuman capacity for hard work. His title is Commissar of Foreign Affairs, but there is not the slightest doubt in anyone's mind that he is in every sense the head of the government. He is described by his comrades as a "great agitator," a man of real revolutionary talent, a "genuine Socialist statesman," the "first statesman Hungary has had in seventy years." Their eyes glow with pride in him. "The rest of us are nothing," said Lukacs, Commissar of Education. "We do our part, but there are hundreds like us in every country." It is nothing to the European movement whether we are hanged tomorrow or not. If Kun were killed it would be a serious loss to the revolution."

Bela Kun gave me a written message to the workers of America, which I cabled for publication in the July number of The Liberator.

He also gave me written answers to some of the questions that were in our minds in America. He said that they had learned much from the experience of Russia - both what to do and what to avoid. Perhaps it was a reflection of his own personal growth in Russia that made him say, "We certainly learned, from the Russian example, self-sacrifice."

He also said, "We learned the proper form of dictatorship there."

I asked him whether the Hungarian dictatorship was more or less strict than the Russian, and he said it was more strict. "The Russians made many experiments," he said, "before they found the proper form of dictatorship. We have been saved those experiments."

I asked him whether he found necessary a complete suppression of free speech and press, and this is his reply:

"We do not practice general suppression of free speech and free press at all. Workmen's papers are published without the intervention of any censorship. Among workingmen there is perfect freedom of speech and of holding meetings; this freedom is enjoyed not only by the workmen who share our views but also by those whose views are different. The anarchists, for instance, publish a paper and other printed matter. There are also citizens' papers, for instance, the Twentieth Century, a periodical published by the society for sociology, without any control or restriction being exercised upon it. We only suppress bourgeois papers having decided counter-revolutionary intentions.

"We are doing this not because we are afraid of them, but because we want in this way to obviate the necessity of suppressing counter-revolution by force of arms."

(6) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

The Liberator, with Max and his sister Crystal Eastman as editors-in-chief-and my old friend Hallinan, now in London, as one of the contributing editors-came out in February, 1918. Soon we were printing the utterances of Lenin. There was true revolutionary leadership now in the world - if we could only understand it. At least we could tell the truth about Russia. Socialism that meant what it said, took back its old name-Communism. There was a new International coming into existence. In America, the rank-and-file Socialists had under the impact of war stood by their Socialist principles, though deserted by most of their leaders-but not by Eugene V. Debs, who said: "I am a Bolshevik from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet." But Socialism in America would take a long time finding out where it stood.

(7) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1964)

There was one big difference between the Masses and the Liberator; in the latter we abandoned the pretense of being a co-operative. Crystal Eastman and I owned the Liberator, fifty-one shares of it, and we raised enough money so that we could pay solid sums for contributions.

The list of contributing editors, largely brought over from the Masses, reads as follows: Cornelia Barns, Howard Brubaker, Hugo Gellert, Arturo Giovannitti, Charles T. Hallinan, Helen Keller, Ellen La Motte, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Louis Untermeyer, Charles Wood, Art Young.

Later Claude McKay, the Negro poet, became an associate editor. At a New Year's party in 1921, we elected Michael Gold and William Gropper to the staff - two opposite poles of a magnet: Gropper as instinctively comic an artist as ever touched pen to paper, and Gold almost equally gifted with pathos and tears.

(8) In his autobiography, A Long Way From Home, the writer, Claude McKay described what it was like to have his poem, If We Must Die, in The Liberator.

The Liberator was a group magazine. The list of contributing editors was almost as exciting to read as the contributions themselves. There was a freeness and a bright new beauty in those contributions, pictorial and literary, that thrilled. And altogether, in their entirety, they were implicit of a penetrating social criticism which did not in the least overshadow their novel and sheer artistry. I rejoiced in the thought of the honour of appearing among the group.

(9) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

Back in New York, I found that life had adjusted itself remarkably well to my absence. Nobody expected me back so soon. Somebody else had my job on the Liberator; my girl seemed to have fallen in love with somebody else; I had no place to live, and no money - I had sent all I had in the bank to my family when I went into the army.

I wrote something and sold it to Frank Harris - that curious, loud, gentle, bombastic old pirate who was running Pearson's Magazine. He told fascinating stories of his friendships with Wilde, Shaw and other great men; but he told them over and over; and how he boomed! He loved poetry, and recited it well. He had a beautiful young wife, and he set an excellent table and served a wine that could be drunk with pleasure. He liked me, and I had a curious almost filial affection for him, though he bored me with his bragging. He said he would print anything I wrote for him, and what was more, he would make an exception in my favor and pay me for what I wrote. And he did, too.

(10) Paul M. Buhle, A Dreamer's Paradise Lost (1995)

By 1917, the Masses was suppressed, its editors and artists placed upon trial... The poetic sensibility of the Masses passed, in large part, over to the Liberator, a physically smaller and more politically focused weekly. Most of the outstanding Ashcan artists had in any case already abandoned ship during a 1916 internal struggle at the Masses over the demand for more clearly political cartoons. Boardman Robinson remained, joined by Hugo Gellert, William Gropper, Reginald Marsh, and various talented cartoonists. Floyd Dell's spirited literary columns continued to highlight figures like Sherwood Anderson, to uphold the sheer beauty of poetry, and to engage in an eclectic variety of literary proposals (such as a turn from Naturalism to a more "scientific" realism) he had foreshadowed in the New Review.

But things had changed in a deeper sense. Symptomatically, the opening of New York's Sheridan Square along with the expansion of the West Side subway set off a hyper-wave of new construction in Greenwich Village, raising rents, inviting tourists, and reducing bohemianism to an increasingly empty spectacle. The "end of innocence" came to the Village just as national journalists spread a version of its values (or at least, its looser sexual morals) to "Country Club" youth in the hinterlands.

The Liberator actually outpaced the Masses circulation, rising finally to eighty thousand. It had gripping labor reportage and a coverage of African-American life (including outstanding black editor, poet, and future novelist Claude McKay) hitherto unimaginable. Its main appeal was symptomized by John Reed's 1918 reports from the "New Russia." Willy-nilly, despite its continued independent-mindedness and literary experimentation, the Liberator had become a Russian-oriented, proto-Communist magazine."

The displacement of a vaguely anarchistic sensibility, full of the self-parodies the Masses pages often featured about the intelligentsia at work and at play, soon left almost nothing behind. Only "Mass Action" of a proto-revolutionary kind could, one imagines, have restored the poetic verve of the middle 1910s, precisely because no mass action was likely to be directed by any all-dominant political movement of the Left. Irrationalism in the best sense would have been vindicated again.