Hugo Gellert

Hugo Grünbaum, the oldest of six children, was born in Budapest, Hungary on 3rd May, 1892. His family immigrated to New York City in 1906, eventually changing their family name to Gellert.

Hugo Gellert attended art school at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and the National Academy Museum and School of Fine Arts. As a student, he designed posters for movies and theater, and also worked for Tiffany Studios.

As Paul Buhle pointed out: "Gellert reached his artistic turning point when he attended the National Academy of Design and won a prize trip in 1914 to Paris. He intended to enroll at the Académie Julian, but instead was drawn to the sweeping style of contemporary commercial art, specifically the Michelin tire posters. After a walking tour across Europe, he returned to New York and drew anti-war cartoons for the Hungarian American daily Elöre, while making his living in commercial lithography."

Gellert travelled to Europe and witnessed the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. On his return to New York City he began to contribute drawings to the Hungarian-American workers' movement's newspaper, Elöre. He also had his work published in The Masses and during this period became friendly with a group of anti-war journalists and cartoonists such as Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, John Reed, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Lydia Gibson, K. R. Chamberlain, Henry J. Glintenkamp, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

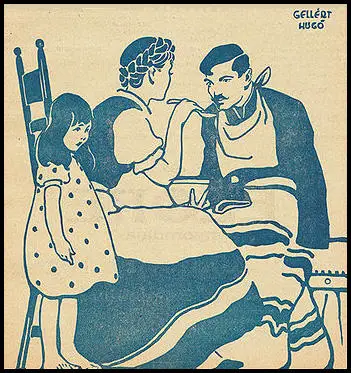

Hugo Gellert caused a political storm when Elöre published his cartoon, Out of the War, in February 1916, that showed an armless veteran being spoon-fed. His anti-war cartoons were also published in other left-wing journals. James Wechsler has pointed out: "Hugo Gellert... is perhaps more infamous for his passionate commitment to leftist political agitation than for his contribution to American art, but Gellert strongly disavowed any distinction between the two. He professed that, for him, political agitation and art were the same thing."

In 1917 Hugo's brother, Ernest Gellert, also a socialist, was drafted into the military but refused to serve on the grounds that he was a conscientious objector. He died of a gunshot wound while imprisoned at Fort Hancock, New Jersey. The army claims his death was a suicide but the circumstances are suspicious. Gellert fled to Mexico to avoid conscription but still continued to provide ant-war cartoons for left-wing newspapers and magazines.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, left-wing journals came under government pressure to change its anti-war policy. When The Masses refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that articles by Floyd Dell and Max Eastman and cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

Henry J. Glintenkamp fled the country for Mexico but the others stood trial in April, 1918. Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. After three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of the defendants.

The second trial was held in January 1919. John Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, was also arrested and charged with the original defendants. Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933): "While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't conspired to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling." This time eight of the twelve jurors voted for acquittal. As the First World War was now over, it was decided not to take them to court for a third time.

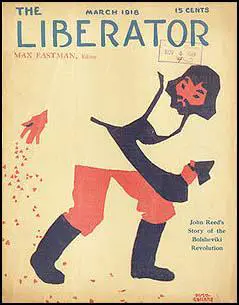

In 1918 the same people who produced The Masses, including the editor, Max Eastman, went on the publish a very similar journal, The Liberator. Hugo Gellert was chosen to draw the cover of its first issue in March, 1918.

In 1922 the journal was taken over by Robert Minor and the American Communist Party. and in 1924 was renamed as The Workers' Monthly. Many of the people who contributed to the The Masses and the original Liberator, were unhappy with this development and in 1926, they started their own journal, the New Masses. Over the next few years Gellert was a major contributor to this magazine. In 1928, he created a mural for the Worker's Cafeteria in Union Square.

Hugo Gellert was a great friend of John Reed, who died of typhus while in Moscow in 1920. Gellert wrote: "The heroism of the American revolutionary vanguard, the doffed struggles of the workers and farmers in spite of jail, tear-gas and bullets are the source of a new, vigorous art movement in America worthy of the tradition of John Reed - poet and brilliant journalist - a pioneer in American working class culture, a hero and a martyr of the victorious Russian worker's revolution." In 1929 he joined with William Gropper, Jacob Burck, Anton Refregier and Louis Lozowick, to establish the first John Reed Club. The group held classes and exhibitions in New York City. Later, these clubs were formed all over the country.

Despite his left-wing activism Gellert worked as a staff artist at The New Yorker Magazine. In 1932, Gellert was invited to participate in a mural exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and submitted a political mural about the connection between industrialists and underworld criminals, entitled, Us Fellas Gotta Stick Together - Al Capone. The museum attempted to censor the mural, along with the murals of William Gropper and Ben Shahn. Other artists threatened to boycott the exhibition over the censorship and they were eventually successful in restoring them to the show. However, they were not reproduced in the catalogue.

In 1933 Gellert illustrated Karl Marx's Capital in Lithographs, and in 1935, he wrote a Marxist, illustrated satire called Comrade Gulliver, An Illustrated Account of Travel into that Strange Country the United States of America. This was followed by Aesop Said So (1936).

After the Second World War Gellert became increasingly concerned with the growth of the extreme right in the United States. His attacks on Joseph McCarthy led to him being called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Gellert refused to answer any questions and as a result was blacklisted.

In 1954, Gellert established the Art of Today Gallery in New York City with Rockwell Kent, Maurice Becker and Charles Wilbert White, for blacklisted artists. Gellert served as the gallery's secretary until it closed in 1957. As Paul Buhle explained: "During the 1950s-1970s, he continued to contribute his art widely, on racism, militarism, and the cause of unionism."

Hugo Gellert died in Freehold Township, New Jersey on 9th December, 1985.

Primary Sources

(1) Hugo Gellert, Karl Marx's Capital in Lithographs (1935)

In the "Democratic" countries - U. S. A., England, France, etc., - police clubs force the jobless millions to submit to starvation. In our America we live in a period of the greatest expropriation in history since we took the land from the Indian possessors. (Brave pioneers risked their lives for this land; now crafty bankers grab it, risking nothing.) Throughout our Southern states our black brothers have always known slavery. Under the N. R. A. President Roosevelt makes slaves of all workers with the aid of strike proof "labor unions," after the pattern of Mussolini. Our last vestige of protection against the rapacious Trusts is being removed.

"Savants" seriously talk of scrapping machines. They advocate a curb on inventions and scientific experiments. Cotton is destroyed. (Even the plow becomes an instrument of destruction.) Wheat is burned. Fruit is dumped into the ocean. Milk is poured into sewers, and hogs are slaughtered for fertilizer, while thousands of human beings die of hunger. The instruments of War are made ready to deal death and destruction.

Yesterday threatens to devour to-morrow.

But out of the East rises a new Prometheus. And all the Gods in the World cannot chain him! The great disciple of Karl Marx, Lenin, led the Russian workers and peasants who created the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics. And these workers and peasants became the Masters of their own destiny. The Young Giant with his mighty hands builds the future of mankind and bright lights flare up in his wake....

The disinherited of the Earth are inspired by his example. They gain strength and courage and strike out for that higher form of society - the New World: plenty for all, a place in the Sun for everybody. But no place will remain for Masters in a World where no one is privileged to despoil his fellowmen. Fascism is the Master's last desperate effort to retain power, to chain us to the past, to rob us of our birthright to the future, to bar us from creating a World worthy of Man.

"We are many - they are few."

Das Kapital is our guide. Like the X-ray, it discloses the depths below the surface. it is my hope that in this abbreviated form the immortal work of Karl Marx will become accessible to the Masses: To the huge army of workers without jobs and farmers without land; to the workers in mills and mines, to all who toil with brain or brawn. This book is made for them. For my existence -- and yours, depends upon them: "Labor is a necessary condition of all human existence, and one which is independent of the forms of society. It is through all the ages a necessity imposed by nature itself, for without it there can be no interchange of material between man and nature -- in a word, no life."

The translation into graphic form of the revolutionary concepts of Das Kapital was a source of inspiration and stimulus. Other revolutionary artists will find in the works of our great working-class leaders - Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin - a wealth of material for their best creative efforts.

The heroism of the American revolutionary vanguard, the doffed struggles of the workers and farmers in spite of jail, tear-gas and bullets are the source of a new, vigorous art movement in America worthy of the tradition of John Reed - poet and brilliant journalist - a pioneer in American working class culture, a hero and a martyr of the victorious Russian worker's revolution.

In this book only the most essential parts of the original text are given. But with the aid of the drawings the necessary material for the understanding of the fundamentals of Marxism is included.

(2) James Wechsler, Hugo Gellert: History of a Controversy (undated)

Hugo Gellert was born in Hungary in 1892 and emigrated to the United States with his family in 1906. Gellert died in 1985. He was a very well-known artist in this country during the 1930s, yet he has essentially been forgotten. Today he is perhaps more infamous for his passionate commitment to leftist political agitation than for his contribution to American art, but Gellert strongly disavowed any distinction between the two. He professed that, for him, political agitation and art were the same thing.

Gellert's activities contributed greatly to the political tone of 1930s American art. He occupied a seminal position in organizing the Artist's Committee for Action and the Artists' Union, two pivotal institutions which greatly contributed to the instigation and perpetuation of the federally funded WPA art programs. He served on the editorial committee of Art Front, the Artists' Union's official publication.

A Gellert drawing adorned the masthead of the premier issue (a Stuart Davis drawing appeared on the cover). Later in the 1930s, Gellert helped organize the American Artists' Congress of February, 1936, at which he gave the keynote address. He spoke at the second American Artists' Congress in December, 1937 as well. Also in late 1937, Gellert became involved with the Artists' Coordination Committee for the National Exhibition of Contemporary American Art at the 1939 New York World's Fair. At the same time, heedful of artists' best interests, Gellert oversaw the formation of a labor union to protect the rights of muralists and their assistants as the World's Fair was being planned.

Gellert painted a spectacular mural imbued with the technological optimism that was so pervasive in 1930s modernism for the Communications Building at the Fair. He painted two other murals in New York City during the 1920s and 1930s as well. All have been destroyed. The earliest, painted for the Workers Party Cafeteria on Union Square, dates from 1928. Gellert had been invited to Moscow by the State Publishing House to design book jackets for Russian editions of Theodore Dreiser's books. The mural was the first project Gellert undertook upon his return to New York. Highly influenced by Russian Modernism of the 1920s, it is one of the first modernist murals in the United States, just predating the North American commissions of Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco. In November, 1928, shortly after the mural's unveiling, the New Yorker declared, "The Gellert murals are the only ones on this continent except those of Rivera in Mexico City that are really contemporary." Eight feet high, Gellert's mural covered one entire wall, eighty feet long, and a facing wall, thirty feet long. The long wall included a frieze of monumental, brightly colored, sculpturally rendered, industrial workers standing before precisionist factories and mine structures. The mural was destroyed when the building was demolished in 1954.

The Seward Park murals are by no means the only work by Gellert to have caused controversy. He excelled at making trouble with his art. In 1932 Gellert captured headlines in New York through an incident involving a mural study that he was invited to submit to the Museum of Modern Art's Murals by Painters and Photographers exhibition. Gellert's painting, Us Fellas Gotta Stick Together (Collection of The Wolfsonian, Miami Beach, FL), along with Ben Shahn's famous The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY) and a painting by William Gropper, was rejected for the exhibition because it featured unflattering portraits of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (whose wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, essentially founded the museum in 1929), J. P. Morgan, Henry Ford and President Herbert Hoover.