Henry J. Glintenkamp

Henry J. Glintenkamp, the son of Hendrik and Sophie Dietz Glintenkamp, was born in Augusta, New Jersey, 1887. Glintenkamp received his elementary art training at the National Academy of Design (1903-1906) under Robert Henri and for a time shared the studio of Stuart Davis. He exhibited at the Armory Show in 1913.

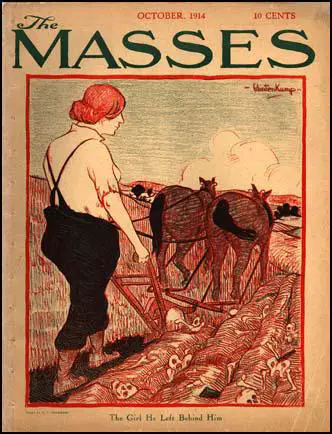

Glinkenkamp was a cartoonist who regularly contributed to the radical journal, The Masses. The journal was founded in New York in 1911 by Piet Vlag. Another important financial backer was Amos Pinchot, a wealthy lawyer who supported a wide variety of progressive causes. Organised like a co-operative, artists and writers who contributed to the journal shared in its management.

Max Eastman was appointed editor and in December, 1912, wrote: "This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers... We do not enter the field of any Socialist or other magazine now published, or to be published. We shall have no further part in the factional disputes within the Socialist party; we are opposed to the dogmatic spirit which creates and sustains these disputes. Our appeal will be to the masses, both Socialist and non-Socialist, with entertainment, education, and the livelier kinds of propaganda."

One of its main contributors, Art Young later recalled: "I think we have the true religion. If only the crusade would take on more converts. But faith, like the faith they talk about in the churches, is ours and the goal is not unlike theirs, in that we want the same objectives but want it here on earth and not in the sky when we die."

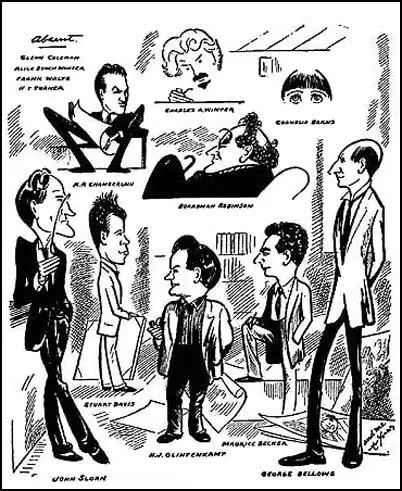

Over the next few years The Masses published articles and poems written by people such as John Reed, Sherwood Anderson, Crystal Eastman, Hubert Harrison, Inez Milholland, Mary Heaton Vorse, Louis Untermeyer, Randolf Bourne, Dorothy Day, Arturo Giovannitti, Michael Gold, Helen Keller, William English Walling, Anna Strunsky, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge, Floyd Dell and Louise Bryant. It also published the work of important artists including John Sloan, Robert Henri, Alice Beach Winter, Mary Ellen Sigsbee, Cornelia Barns, Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Lydia Gibson, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, Hugo Gellert, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

Max Eastman, the editor of The Masses, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system. Eastman and journalists such as John Reed who reported the conflict for the journal, argued that the USA should remain neutral. Most of those involved with the journal agreed with this view but there was a small minority, including William Walling and Upton Sinclair, who wanted the USA to join the Allies against the Central Powers.

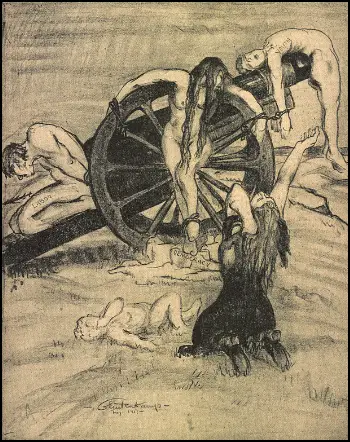

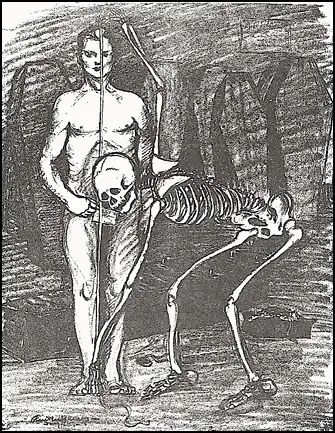

labeled "labor" and "youth," and one woman, labeled "democracy," chained to a cannon.

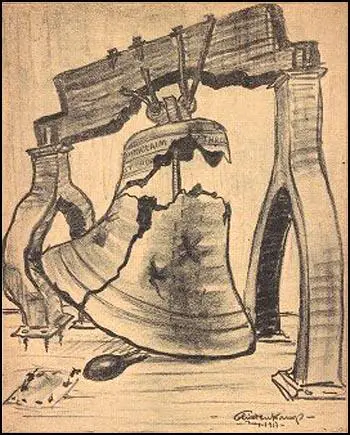

Glintenkamp believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the journal came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that articles by Floyd Dell and Max Eastman and cartoons by Glintenkamp, Art Young and Boardman Robinson had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

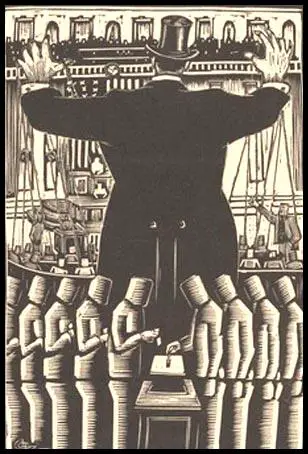

The Masses reported in September, 1917: "The Post Office was represented by Assistant District Attorney Barnes. He explained that the Department construed the Espionage Act as giving it power to exclude from the mails anything which might interfere with the successful conduct of the war. Four cartoons and four pieces of text in the August issue were specified as violations of the law. The cartoons were Boardman Robinson's Making the World Safe for Democracy, H. J. Glintenkamp's Liberty Bell and the conscription cartoons, and one by Art Young on Congress and Big Business. The conscription cartoon was considered by the Department "the worst thing in the magazine". The text objected to was A Question, an editorial by Max Eastman; A Tribute, a poem by Josephine Bell; a paragraph in an article on Conscientious Objectors; and an editorial, Friends of American Freedom."

Glintenkamp fled the country and went to live in Mexico, but the others stood trial in April, 1918. Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. After three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of Dell and his fellow defendants.

The second trial was held in January 1919. John Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, was also arrested and charged with the original defendants. Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933): "While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't conspired to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling." This time eight of the twelve jurors voted for acquittal. As the First World War was now over, it was decided not to take them to court for a third time.

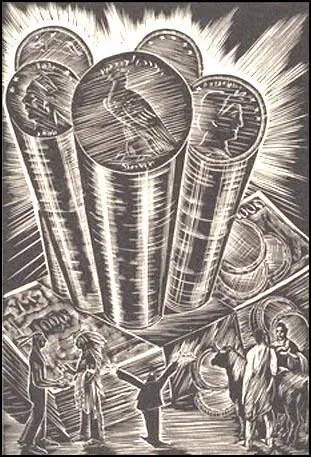

Glintenkamp returned to the United States and continued to produce art work highly critical of capitalism. He was especially active during the Great Depression producing work such as

Henry J. Glintenkamp died in 1946.

Primary Sources

(1) The Masses (September, 1917)

The Post Office was represented by Assistant District Attorney Barnes. He explained that the Department construed the Espionage Act as giving it power to exclude from the mails anything which might interfere with the successful conduct of the war.

Four cartoons and four pieces of text in the August issue were specified as violations of the law. The cartoons were Boardman Robinson's Making the World Safe for Democracy, H. J. Glintenkamp's Liberty Bell and the conscription cartoons, and one by Art Young on Congress and Big Business. The conscription cartoon was considered by the Department "the worst thing in the magazine". The text objected to was A Question, an editorial by Max Eastman; A Tribute, a poem by Josephine Bell; a paragraph in an article on Conscientious Objectors; and an editorial, Friends of American Freedom.

(2) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

The Masses harassed by the post-office authorities, was suppressed in October, 1917, by the Government, and its editors were indicted, myself among them, under the so-called Espionage Act, which was being used not against German spies but against American Socialists, Pacifists, and anti-war radicals. Sentences of twenty years were being served out to all who dared say this was not a war to end war, or that the Allied loans would never be paid. But the courts would probably not get around to us until next year; and we immediately made plans to start another magazine, The Liberator, and tell more truth; we would stand on the pre-war Wilsonian program, and call for a negotiated peace.

(3) Amos Pinchot, The Liberator (June, 2018)

The prosecution of the editors of The Masses for "conspiracy to obstruct recruiting and enlistment" is an attack on the lawful freedom of the press.

It is not an attempt to defend the country against conspirators, spies, or any other classes of criminals contemplated by those who framed the espionage law.

It is an attempt to put four American citizens in jail for expressing their lawful opinions. And it is the culmination of a series of acts which the New York Evening Post has described as "governmental persecution."

Not one word of evidence to prove that these men ever wrote to each other, or ever discussed the subject of the draft or enlistment with each other, after the passage of the espionage law, was adduced by the government.

Not a word of direct evidence that they intended to, or wanted to, or ever even imagined or discussed the possibility that they might obstruct recruiting or enlistment.

No pretense that they ever made an attempt to reach with their magazine men of draft age or men eligible for enlistment.

No pretense that anybody was ever deterred by them from enlisting or registering under the law.

No pretense that they ever received a cent of German or pro-German money, or that they had any pro-German friends or connections, or anything but hatred for German militarism and the German imperial government.

The prosecution's evidence of conspiracy consisted solely of the open publication by these men of their opinions about the war and about the principle of conscription, and the rights of conscientious objectors, in a magazine which they owned and published without profit for the sake of individual expression.

In addition to the August, September and October issues of this magazine the government produced a telegram and a few letters written individually by two of the defendants to persons in no way connected with the case and before the espionage law was passed, in which similar opinions were expressed-none of them addressed to prospective soldiers, none of them advising against enlistment or registration. In not one of these letters was there a statement of opposition to the war or to conscription as vigorous as those openly published in the magazine.

The prosecution adduced two issues of The Masses that were written, printed and distributed before the espionage law was passed, and every extreme statement of opposition to war and to conscription in those issues was diligently and repeatedly read to the jury as of equal import with those published after the law was passed.

Upon such evidence, the bulk of it relating to facts ante-dating the passage of the law under which the defendants were indicted, and none of it proving an intent to obstruct recruiting or enlistment, and none of it even tending to prove a conspiracy, or any kind of a plan or arrangement among the defendants, the government is attempting, by working upon the wartime prejudice and excitement of a jury, to send these American citizens to prison.

The defense established by uncontradicted testimony the following facts, not only proving that there was no conspiracy and no intent to violate the law, but proving that every effort was made by the defendants to secure a definition of the law, and confine their expressions of opinion to it:

(1) The business manager took one of the issues adduced by the prosecution to George Creel, who was then supposed to be the national censor, in order to make sure that there was nothing unlawful in it. Creel himself testified that he understood this to be the purport of the visit, and that he had said it contained nothing in violation of the law, so far as he knew.

(2) The editors of The Masses never held a meeting or any conference to plan out a future issue of The Masses during the time described in the indictment. Art Young was in Washington practically the whole time. Max Eastman was absent from the office almost continually. The magazine was made up, as usually in the summer months, by Floyd Dell or his assistant, from the material voluntarily submitted by the contributing editors.

(3) No committee with authority to reject contributions from the contributing editors and owners of the magazine was present during this time, and no such contribution was rejected.

(4) The defendants themselves first brought this case into the courts. In July, exactly when the alleged conspiracy would have been at its height, they went before Judge Learned Hand and asked for an injunction compelling the Post Office to admit their August issue into the mail.

(5) The injunction was granted and although it was stayed by an appeal on the part of the Post Office, it was under the influence of this judicial decision in their favor that the defendants brought out the other two issues cited in the indictment.

(6) After the suppression of the August number The Masses Publishing Company wrote to the Post Office Department asking for specific rulings on the things contained in their magazine so that they could make up future magazines in compliance with the Post Master General's interpretation of the law. These requests were frequently repeated, and never answered in any way by the department at Washington.

(7) In September Max Eastman brought the matter to the attention of the President, so confident was he that his expression of opinions had not violated any law, and he received a cordial letter from the President in reply.

(8) In October Max Eastman, in company with E. W. Scripps, the head of the United Press Association, called upon the Post Master General, to make application for a new mailing privilege, and received from him the promise of a reply within a week. He never received any reply, and from that day to this his letters and telegrams to the Post Office Department at Washington have been absolutely ignored.

These facts, proving that there was no conspiracy and no unlawful intent, were established by the defense without contradiction-in opposition to the prosecution's case in which no evidence of conspiracy or unlawful intent beyond the mere individual publication of opinions was adduced.

After a trial lasting two weeks, in a room whose windows opened upon a liberty bond booth where patriotic airs were played by a brass band for several hours every day, and in which every device of patriotic argument and emotion was employed, and in which practically everything the defendants had said since and even before the war was declared was admitted, while the defendants made no apology for their opinions, but conceded and re-read all that they had written, the jury, which was kept out two nights and a day and a half, failed to agree on a verdict.

It is the opinion of every impartial person that such a disagreement in times like these, and in the face of a violent newspaper propaganda for conviction, was a victory and vindication of the defendants. Nevertheless the government has moved for an immediate retrial.

Justice and liberty are on the side of these defendants and we, urge you to give them whatever support you can. In defending them we shall be defending a vitally important public principle,-the maintenance of constitutional rights in war-time. The free-press issue is more clearly presented in this case than in any brought into court since the war began. Lawyers for the prosecution as well as lawyers for the defense declare it to be the most important case before the country today.

(4) The Masses (September, 1917)

The Post Office was represented by Assistant District Attorney Barnes. He explained that the Department construed the Espionage Act as giving it power to exclude from the mails anything which might interfere with the successful conduct of the war.

Four cartoons and four pieces of text in the August issue were specified as violations of the law. The cartoons were Boardman Robinson's Making the World Safe for Democracy, H. J. Glintenkamp's Liberty Bell and the conscription cartoons, and one by Art Young on Congress and Big Business. The conscription cartoon was considered by the Department "the worst thing in the magazine". The text objected to was A Question, an editorial by Max Eastman; A Tribute, a poem by Josephine Bell; a paragraph in an article on Conscientious Objectors; and an editorial, Friends of American Freedom.

(5) In his autobiography, Homecoming (1933), Floyd Dell explained his thoughts on being charged with breaking the Espionage Act.

While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't 'conspired' to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling.

Rumours began to perculate. "Six to six." Next morning the debate in the jury-room grew fiercer, noisier. At noon the jury came in, hot, weary, angry, limp, and exhausted. They had fought the case amongst themselves for eleven vehement hours. And they could not agree upon a verdict.

But the judge refused to discharge them; and they went back, after further instructions, with grim determination on their faces.

At eleven o'clock the jurors reported continued disagreement, but were sent back. The next noon, hopelessly deadlocked, the jury was discharged, with all our thanks. And so we were free.