Stuart Davis

Stuart Davis was born in Philadelphia on 7th December, 1894. His father was the art editor of the Philadelphia Press. At the age of sixteen Davis began studying at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri, leader of what became known as the Ash Can School. Davis developed left-wing views and in 1911 began contributing pictures to the radical journal, The Masses.

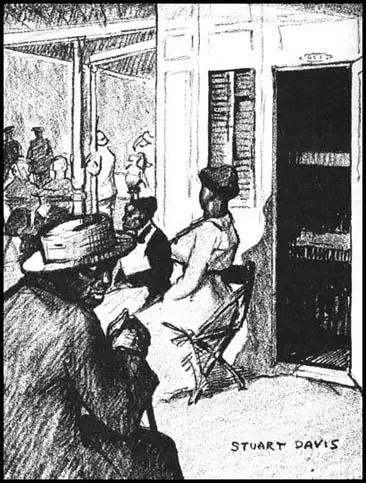

Claude McKay has argued: "Some times the magazine (The Masses) repelled me. There was one issue particularly which carried a powerful bloody brutal drawing by Robert Minor. The drawing was of Negroes tortured on crosses deep down in Georgia. I bought the magazine and tore the cover off, but it haunted me for a long time. There were other drawings of Negroes by an artist named Stuart Davis. I thought they were the most superbly sympathetic drawings of Negroes done by an American. And to me they have never been surpassed."

In 1923 Davis moved to New Mexico where he painted still-lifes. He also began experimenting with Cubism but it was only after spending a year in Paris that he developed his own distinctive style. His abstract patterns that included lettering was inspired by advertisement posters.

During the 1930s Davis became art editor of the Artists' Congress magazine, Art Front. He also painted several public murals including: Men Without Women (1932), Swing Landscape (1938) and History of Communication (1939).

Stuart Davis, a strong defender of modern art, died in 1964.

Primary Sources

(1) Charlotta Russell Lowell, letter to The Masses (May, 1915)

There is one thing about The Masses that strikes me as totally inconsistent with its general policy: it is the way in which the negro race is portrayed in its cartoons. If I understand The Masses rightly, its general policy is to inspire the weak and unfortunate with courage and self-respect and to bring home to the oppressors the injustice of their ways. Your pictures of coloured people would have, I should think, exactly the opposite effect. They would depress the negroes themselves and confirm the whites in their contemptuous and scornful attitude.

(2) Max Eastman, The Masses (May, 1915)

Miss Lowell makes the most serious charge against The Masses we have heard. We have been accused of bringing the human race as a whole into disrepute often enough, and our love of realism has bourne us up under the charge. But if that same realism when engaged in representation of the negro, seems to align us upon the side of the self-conceited white in the race-conflict that afflicts the world, it is indeed tragic.

Stuart Davis portrays the coloured people he sees with exactly the same cruelty of truth, with which he portrays the whites. He is so far removed from any motive in the matter but that of art, that he cannot understand such a protest as Miss Lowell's at all.

(3) Claude McKay, A Long Way Home (1937)

The Masses was one of the magazines which attracted me when I came to New York in 1914. I liked its slogans, its make-up, and above all, its cartoons. There was a difference, a freshness in its social information. And I felt a special interest in its sympathetic and iconoclastic items about the Negro.

Some times the magazine repelled me. There was one issue particularly which carried a powerful bloody brutal drawing by Robert Minor. The drawing was of Negroes tortured on crosses deep down in Georgia. I bought the magazine and tore the cover off, but it haunted me for a long time. There were other drawings of Negroes by an artist named Stuart Davis. I thought they were the most superbly sympathetic drawings of Negroes done by an American. And to me they have never been surpassed.