Louis Untermeyer

Louis Untermeyer was born in New York City on 1st October, 1885. After a brief formal education he left high school without graduating and found work with his father's jewelry manufacturing company.

Untermeyer was very interested in literature and in 1911 he published his first book of poetry, First Love. He also held left-wing political views and was the literary editor of the Marxist journal, The Masses. The assistant editor of the journal, Floyd Dell, later recalled: "The Masses' literary editor, Louis Untermeyer, who had written about poetry for the Friday Review, was a friend already; we were interested in the same things, and lunched together frequently to discuss the universe."

Like most people involved with the journal, Untermeyer believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system. Untermeyer and journalists such as John Reed who reported the conflict for The Masses, argued that the USA should remain neutral. After the USA entered the First World War the team working on The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges.

In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that articles in the journal by Floyd Dell and Max Eastman and cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and H. J. Glintenkamp had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable." Untermeyer and his friends went on the publish a very similar journal, The Liberator.

By 1923 Untermeyer was vice-president in his father's company but he decided to resign and concentrate on writing. Over the next fifty years he wrote, edited or translated over one hundred books. This included several volumes of his own poetry. He also produced a series of anthologies, notably Modern American Poetry (1919), Modern British Poetry (1920), This Singing World (1923) and Selected Poems and Parodies (1935).

Untermeyer also lectured on poetry, drama and music. In 1939 he was appointed Poet in Residence at the University of Michigan. He also held the same post at the University of Kansas and Iowa State College. In 1939 he published his autobiography From Another World.

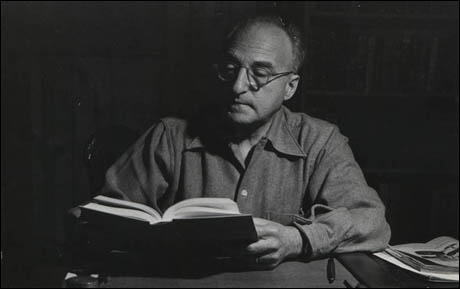

Arthur Miller knew him during this period: "Louis Untermeyer, then in his sixties, was a poet and anthologist, a distinguished-looking old New York type with a large aristocratic nose and a passion for conversation, especially about writers and to become a poet... All this with wisecracking and banter, at which Louis was a lovable master, what with his instant recall of every joke and pun he had ever heard."

Untermeyer was an entertaining talker and in 1950 became a panelist on the television programme, What's My Line. He continued to be active in campaigning for left-wing causes and as a result the FBI had been collecting a file of his activities. His name was also mentioned during the House of Un-American Activities Committee investigation into communist subversion. This was brought to the attention of the television industry and in 1951 Untermeyer was sacked from the television show and was blacklisted. Like many left-wing artists during this period, Untermeyer became a victim of McCarthyism.

In his autobiography, Timebends - A Life (1987), Arthur Miller, explained how Untermeyer responded to this victimization: "Louis went back to his apartment. Normally we ran into each other in the street once or twice a week or kept in touch every month or so, but I no longer saw him in the neighborhood or heard from him. Louis didn't leave his apartment for almost a year and a half. An overwhelming and paralyzing fear had risen him. More than a political fear, it was really that he had witnessed the tenuousness of human connection and it had left him in terror. He had always loved a lot and been loved, especially on the TV program where his quips were vastly appreciated, and suddenly, he had been thrown into the street, abolished."

In 1956 Untermeyer was awarded a Gold Medal by the Poetry Society of America. He also served as a consultant in English poetry for the Library of Congress from 1961 until 1963.

Louis Untermeyer died on 18th December, 1977.

Primary Sources

(1) Louis Untermeyer's poem, Sunday, about the police action during the Lawrence Textile Strike, appeared in The Masses in April 1913.

Down the rapt and singing streets of little Lawrence

Came the stolid columns; and, behind the blue-coats,

Grinning and invisible, bearing unseen torches,

Rode red hordes of anger, sweeping all before them.

Lust and Evil joined them - Terror rode among them,

Fury fired its pistols, Madness stabbed and yelled

Down the wild and bleeding streets of shuddering Lawrence

Raged the heedless panic, hour-long and bitter;

Passion tore and trampled men more mild and peaceful,

Fought with savage hatred in the name of Law and Order.

And, below the outcry, like the sea beneath the breakers,

Mingling with the anguish rolled the solemn organ.

Eleven in the morning - people were in the church -

Prayers were in the making - God was near at hand -

It was Sunday!

(2) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

The Masses was presently indicted for criminal libel at the complaint of the Associated Press, for saying that it suppressed the news in the Colorado strike; the case was afterwards dropped. The magazine, among other news, told of Frank Tannenbaum's being arrested for leading homeless men into a New York church to sleep. Jack Reed was sending vigorous, realistically beautiful short stories to us from Mexico. I was thrilled when John Sloan drew a picture of a girl being beaten by the matron of a reformatory, to illustrate my story, The Beating. Among The Masses' literary editors, Louis Untermeyer, who had written about poetry for the Friday Review, was a friend already; we were interested in the same things, and lunched together frequently to discuss the universe. At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other, I saw Horatio Winslow, Mary Heaton Vorse, William English Walling, Howard Brubaker; and Art Young, John Sloan, Charles A. and Alice Beach Winter, H. J. Turner, Maurice Becker, George Bellows, Cornelia Barns, Stuart Davis, Glenn O. Coleman, K. R. Chamberlain. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, who was himself hotly propagandist and felt no desire to be unintelligible, spoke up strongly for the artists who lacked parliamentary ability, and defended the extreme artistic-freedom point of view in their behalf. I, who had tried to get up a rebellion against Max Eastman when I first came on the magazine, over some high-handed proceeding of his, had soon become his faithful lieutenant in a practical dictatorship. Once the artists rebelled and took the magazine away from us; but, as they did nothing toward getting out the next issue, Max and I got some proxies from absentee stockholders and took the magazine back. It stood for fun, truth, beauty, realism, freedom, peace, feminism, revolution.

(3) Arthur Miller, Timebends - A Life (1987)

The resurgent American right of the early fifties, the assault led by Senator McCarthy on the etiquette of liberal society, was among other things, a hunt for the alienated, and with remarkable speed conformity became the new style of the hour.

Louis Untermeyer, then in his sixties, was a poet and anthologist, a distinguished-looking old New York type with a large aristocratic nose and a passion for conversation, especially about writers and to become a poet. He married four times, had taught and written and published, and with the swift rise of television had become nationally known as one of the original regulars on What's My Line?, a popular early show in which he, along with columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, publisher Bennett Cerf, and Arlene Francis, would try to guess the occupation of a studio guest by asking the fewest possible questions in the brief time allowed. All this with wisecracking and banter, at which Louis was a lovable master, what with his instant recall of every joke and pun he had ever heard.

One day he arrived as usual at the television studio an hour before the program began and was told by the producer that he was no longer on the show. It appeared that as a result of having been listed in Life magazine as a sponsor of the Waldorf Conference (a meeting to discuss cultural and scientific links with the Soviet Union), an organized letter campaign protesting his appearance on What's My Line? had scared the advertisers into getting rid of him.

Louis went back to his apartment. Normally we ran into each other in the street once or twice a week or kept in touch every month or so, but I no longer saw him in the neighborhood or heard from him. Louis didn't leave his apartment for almost a year and a half. An overwhelming and paralyzing fear had risen him. More than a political fear, it was really that he had witnessed the tenuousness of human connection and it had left him in terror. He had always loved a lot and been loved, especially on the TV program where his quips were vastly appreciated, and suddenly, he had been thrown into the street, abolished.