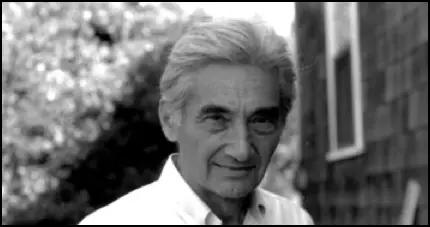

Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn, the son of Jewish immigrants, Edward Zinn, a waiter, and Jennie (Rabinowitz) Zinn, a housewife, was born in Brooklyn in 1922. Zinn later recalled: “We moved a lot, one step ahead of the landlord. I lived in all of Brooklyn’s best slums.”

Zinn attended New York City public schools and after graduating from Thomas Jefferson High School he became a pipe fitter in the Brooklyn Navy Yard where he met his future wife, Roslyn Shechter.

Zinn became very active in left-wing politics and in 1939 he attended a meeting organised by the American Communist Party. "Suddenly, I heard the sirens sound, and I looked around and saw the policemen on horses galloping into the crowd and beating people. I couldn't believe that. And then I was hit. I turned around and I was knocked unconscious. I woke up sometime later in a doorway, with Times Square quiet again, eerie, dreamlike, as if nothing had transpired. I was ferociously indignant... It was a very shocking lesson for me."

A strong opponent of fascism Zinn joined the United States Air Force in 1943. During the Second World War Zinn flew missions throughout Europe. He was awarded the Air Medal, and attained the rank of second lieutenant. In April 1945, he was involved in the bombing of German soldiers based in Royan. "Twelve hundred heavy bombers, and I was in one of them, flew over this little town of Royan and dropped napalm - first use of napalm in the European theater. And we don’t know how many people were killed or how many people were terribly burned as a result of what we did." This experience turned him into an anti-war campaigner.

After the war, Zinn worked at a series of menial jobs until entering New York University on the GI Bill in 1949. He received his bachelor’s degree from NYU, followed by master’s and doctoral degrees in history from Columbia University, where he studied under Henry Steele Commager and Richard Hofstadter. He obtained his PhD with a dissertation about the career of Fiorello LaGuardia. This became the subject of his first book, LaGuardia in Congress (1959). The book was well-received and won the American Historical Association's Albert J. Beveridge Prize.

In 1956, he became the chairmanship of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, an all-black women's school in Atlanta. Zinn made no attempt to hide his political views. One of his students, Alice Walker, remembers how in his first lecture he stated: “Well, I stand to the left of Mao Zedong.” As she pointed out: "It was such a moment, because the people couldn’t imagine anyone in Atlanta saying something like that, when at that time the Chinese and the Chinese Revolution just meant that, you know, people were on the planet who were just going straight ahead, a folk revolution. So he was saying he was to the left of that."

While teaching at the college he joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and during the 1960s was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. His political activities resulted in him losing his job at Spelman College. In 1963, Spelman fired him for "insubordination." Alice Walker argued: "He was thrown out because he loved us, and he showed that love by just being with us. He loved his students. He didn’t see why we should be second-class citizens. He didn’t see why we shouldn’t be able to eat where we wanted to and sleep where we wanted to and be with the people we wanted to be with. And so, he was with us. He didn’t stay back, you know, in his tower there at the school. And so, he was a subversive in that situation."

According to the Los Angeles Times: "During the civil rights movement, Zinn encouraged his students to request books from the segregated public libraries and helped coordinate sit-ins at downtown cafeterias. Zinn also published several articles, including a then-rare attack on the Kennedy administration for being too slow to protect blacks."

In 1964 Zinn became Professor of History at Boston University. Soon afterwards he published his second book, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (1964). This was followed by The Southern Mystique (1964) and New Deal Thought (1966).

Zinn was also one of the leaders of the Anti-Vietnam War protests during the presidencies of Lyndon Baines Johnson and Richard Nixon. When Daniel Ellsberg, an administration official, came out against the war, he gave one copy of the Pentagon Papers Zinn and his wife, Roslyn. As a result of his political activities that he published Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal (1967) and Disobedience and Democracy (1968). Zinn travelled to Hanoi with Father Daniel Berrigan and successfully negotiated the release of three captured US airmen.

Zinn came into conflict with John Silber, the president of Boston University. Zinn twice helped lead faculty votes to oust Silber president, who in turn claimed that Zinn was a prime example of teachers "who poison the well of academe." Zinn was also co-chairman of the strike committee when university professors walked out in 1979. After the strike was settled, he and four colleagues were charged with violating their contract when they refused to cross a picket line of striking secretaries. The charges against "the Boston Five" were soon dropped.

George Binette was one of his students: "At first I found his lectures disorganised, bordering on the chaotic. But I soon came to appreciate that through subtly weaving considerable erudition with personal reminiscence, he was challenging the received and often cherished assumptions about US history among young people. In person Zinn frequently projected a Zen-like calm. He seemed to possess exceptional patience, both for naive admirers and stridently reactionary critics, though he never concealed a zealous passion against injustice. And in contrast to many left-leaning academics, he combined his classroom stance with practical action."

Other books by Zinn included The Politics of History (1970), Postwar America (1973), Justice in Everyday Life (1974). A People's History of the United States was published in 1980 with a first printing of 5,000. However, over the next twenty years it achieved sales of over a million copies. Traditional historians criticised the book but as Zinn pointed out: "There's no such thing as a whole story; every story is incomplete. My idea was the orthodox viewpoint has already been done a thousand times." Noam Chomsky has argued that the book had a tremendous impact on the public: "I can't think of anyone who had such a powerful and benign influence... His historical work changed the way millions of people saw the past."

The book was criticised by liberal and conservative historians. When reviewing the book for the New York Times, the historian, Eric Foner described it as "a deeply pessimistic vision of the American experience" and pointed out that "blacks, Indians, women and labourers appear either as rebels or as victims. Less dramatic but more typical lives - people struggling to survive with dignity in difficult circumstances - receive little attention."

Sean Wilentz, a professor of history at Princeton University, had mixed views on Zinn: “What Zinn did was bring history writing out of the academy, and he undid much of the frankly biased and prejudiced views that came before it. But he’s a popularizer, and his view of history is topsy-turvy, turning old villains into heroes, and after a while the glow gets unreal.”

As he wrote in his autobiography, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train (1994), "From the start, my teaching was infused with my own history. I would try to be fair to other points of view, but I wanted more than 'objectivity'; I wanted students to leave my classes not just better informed, but more prepared to relinquish the safety of silence, more prepared to speak up, to act against injustice wherever they saw it. This, of course, was a recipe for trouble."

In 1988, Howard Zinn took early retirement to concentrate on writing. This including a play about the anarchist leader Emma Goldman. Other books by Zinn include: Declarations of Independence (1990), Zinn Reader (1997), Howard Zinn on History (2001), Zinn on War (2001), Terrorism and War (2002), Emma, a biography of Emma Goldman (2002), Disobedience and Democracy (2002), his autobiography, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train (2002), A Power Governments Cannot Suppress (2006), A Young People's History of the United States (2007) and The Unraveling of the Bush Presidency (2007).

Zinn continued to be active in politics and was highly critical of US troops being used in Iraq and Afghanistan. Zinn argued: "Where progress has been made, wherever any kind of injustice has been overturned, it's been because people acted as citizens, and not as politicians. They didn't just moan. They worked, they acted, they organised, they rioted if necessary to bring their situation to the attention of people in power. And that's what we have to do today."

Howard Zinn died of a heart attack while swimming on 27th January, 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (1980)

Eugene Debs had become a Socialist while in jail in the Pullman strike. Now he was the spokesman of a party that made him its presidential candidate five times. The party at one time had 100,000 members, and 1,200 office holders in 340 municipalities. Its main newspaper, Appeal to Reason, for which Debs wrote, had half a million subscribers, and there were many other Socialist newspapers around the country, so that, all together, perhaps a million people read the Socialist press.

Socialism moved out of the small circles of city immigrants - Jewish and German socialists speaking their own languages - and became American. The strongest Socialist state organization was in Oklahoma, which in 1914 had twelve thousand dues-paying members (more than New York State), and elected over a hundred Socialists to local office, including six to the Oklahoma state legislature. There were fifty-five weekly Socialist newspapers in Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and summer encampments that drew thousands of people.

In 1910, Victor Berger became the first member of the Socialist party elected to Congress; in 1911, seventy-three Socialist mayors were elected, and twelve hundred lesser officials in 340 cities and towns. The press spoke of "The Rising Tide of Socialism."

A privately circulated memorandum suggested to one of the departments of the National Civic Federation: "In view of the rapid spread in the United States of socialistic doctrines," what was needed was "a carefully planned and wisely directed effort to instruct public opinion as to the real meaning of socialism." The memorandum suggested that the campaign "must be very skillfully and tactfully carried out," that it "should not violently attack socialism and anarchism as such" but should be "patient and persuasive" and defend three ideas: "individual liberty; private property; and inviolability of contract."

(2) Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (1980)

During the presidencies of Harding and Coolidge in the twenties, the Secretary of the Treasury was Andrew Mellon, one of the richest men in America. In 1923, Congress was presented with the "Mellon Plan," calling for what looked like a general reduction of income taxes, except that the top income brackets would have their tax rates lowered from 50 per cent to 25 per cent, while the lowest-income group would have theirs lowered from 4 percent to 3 percent. A few Congressmen from working-class districts spoke against the bill, like William P. Connery of Massachusetts:

"I am not going to have my people who work in the shoe factories of Lynn and in the mills in Lawrence and the leather industry of Peabody, in these days of so-called Republican prosperity when they are working but three days in the week think that I am in accord with the provisions of this bill. When I see a provision in this Mellon tax bill which is going to save Mr. Mellon himself $800,000 on his income tax and his brother $600,000 on his, I cannot give it my support.

(3) Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (1980)

It was not Hitler's attacks on the Jews that brought the United States into World War II, any more than the enslavement of 4 million blacks brought Civil War in 1861. Italy's attack on Ethiopia, Hitler's invasion of Austria, his takeover of Czechoslovakia, his attack on Poland - none of those events caused the United States to enter the war, although Roosevelt did begin to give important aid to England. What brought the United States fully into the war was the Japanese attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. Surely it was not the humane concern for Japan's bombing of civilians that led to Roosevelt's outraged call for war - Japan's attack on China in 1937, her bombing of civilians at Nanking, had not provoked the United States to war. It was the Japanese attack on a link in the American Pacific Empire that did it.

In one of its policies, the United States came close to direct duplication of Fascism. This was in its treatment of the Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast. After the Pearl Harbor attack, anti-Japanese hysteria spread in the government. One Congressman said: "I'm for catching every Japanese in America, Alaska and Hawaii now and putting them in concentration camps. Damn them! Let's get rid of them!"

Franklin D. Roosevelt did not share this frenzy, but he calmly signed Executive Order 9066, in February 1942, giving the army the power, without warrants or indictments or hearings, to arrest every Japanese-American on the West Coast - 110,000 men, women, and children - to take them from their homes, transport them to camps far into the interior, and keep them there under prison conditions. Three-fourths of these were Nisei - children born in the United States of Japanese parents and therefore American citizens. The other fourth - the Issei, born in Japan - were barred by law from becoming citizens. In 1944 the Supreme Court upheld the forced evacuation on the grounds of military necessity. The Japanese remained in those camps for over three years.

(4) Howard Zinn, A People's History of the United States (1980)

In the early fifties, the House Un-American Activities Committee was at its heyday, interrogating Americans about their Communist connections, holding them in contempt if they refused to answer, distributing millions of pamphlets to the American public: "One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism" ("Where can Communists be found? Everywhere"). Liberals often criticized the Committee, but in Congress, liberals and conservatives alike voted to fund it year after year. By 1958, only one member of the House of Representatives (James Roosevelt) voted against giving it money. Although Truman criticized the Committee, his own Attorney General had expressed, in 1950, the same idea that motivated its investigations: "There are today many Communists in America. They are everywhere - in factories, offices, butcher shops, on street corners, in private business - and each carries in himself the germs of death for society."

(5) Howard Zinn, interviewed by Amy Goodman (2005)

Well, we thought bombing missions were over. The war was about to come to an end. This was in April of 1945, and remember the war ended in early May 1945. This was a few weeks before the war was going to be over, and everybody knew it was going to be over, and our armies were past France into Germany, but there was a little pocket of German soldiers hanging around this little town of Royan on the Atlantic coast of France, and the Air Force decided to bomb them. Twelve hundred heavy bombers, and I was in one of them, flew over this little town of Royan and dropped napalm - first use of napalm in the European theater.

And we don’t know how many people were killed or how many people were terribly burned as a result of what we did. But I did it like most soldiers do, unthinkingly, mechanically, thinking we’re on the right side, they’re on the wrong side, and therefore we can do whatever we want, and it’s OK. And only afterward, only really after the war when I was reading about Hiroshima from John Hersey and reading the stories of the survivors of Hiroshima and what they went through, only then did I begin to think about the human effects of bombing. Only then did I begin to think about what it meant to human beings on the ground when bombs were dropped on them, because as a bombardier, I was flying at 30,000 feet, six miles high, couldn’t hear screams, couldn’t see blood. And this is modern warfare.

In modern warfare, soldiers fire, they drop bombs, and they have no notion, really, of what is happening to the human beings that they’re firing on. Everything is done at a distance. This enables terrible atrocities to take place. And I think, reflecting back on that bombing raid and thinking of that in Hiroshima and all the other raids on civilian cities and the killing of huge numbers of civilians in German and Japanese cities, the killing of 100,000 people in Tokyo in one night of fire-bombing, all of that made me realize war, even so-called good wars against fascism like World War II, wars don’t solve any fundamental problems, and they always poison everybody on both sides. They poison the minds and souls of everybody on both sides. We’re seeing that now in Iraq, where the minds of our soldiers are being poisoned by being an occupying army in a land where they are not wanted. And the results are terrible.

(6) Mark Feeney and Bryan Marquard, The Boston Globe (27th January, 2010)

In 1997, Dr. Zinn slipped into popular culture when his writing made a cameo appearance in the film "Good Will Hunting." The title character, played by Matt Damon, lauds "A People’s History" and urges Robin Williams’s character to read it. Damon, who co-wrote the script, was a neighbor of the Zinns growing up.

"Howard had a great mind and was one of the great voices in the American political life," Ben Affleck, also a family friend growing up and Damon's co-star in "Good Will Hunting," said in a statement. "He taught me how valuable - how necessary - dissent was to democracy and to America itself. He taught that history was made by the everyman, not the elites. I was lucky enough to know him personally and I will carry with me what I learned from him - and try to impart it to my own children - in his memory."

Damon was later involved in a television version of the book, "The People Speak," which ran on the History Channel in 2009, and he narrated a 2004 biographical documentary, "Howard Zinn: You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train."

"Howard had a genius for the shape of public morality and for articulating the great alternative vision of peace as more than a dream," said James Carroll a columnist for the Globe's opinion pages whose friendship with Dr. Zinn dates to when Carroll was a Catholic chaplain at BU. "But above all, he had a genius for the practical meaning of love. That is what drew legions of the young to him and what made the wide circle of his friends so constantly amazed and grateful."

(7) New York Times (27th January 2010)

Proudly, unabashedly radical, with a mop of white hair and bushy eyebrows and an impish smile, Mr. Zinn, who retired from the history faculty at Boston University two decades ago, delighted in debating ideological foes, not the least his own college president, and in lancing what he considered platitudes, not the least that American history was a heroic march toward democracy.

Almost an oddity at first, with a printing of just 4,000 in 1980, “A People’s History of the United States” has sold nearly two million copies. To describe it as a revisionist account is to risk understatement. A conventional historical account held no allure; he concentrated on what he saw as the genocidal depredations of Christopher Columbus, the blood lust of Theodore Roosevelt and the racial failings of Abraham Lincoln. He also shined an insistent light on the revolutionary struggles of impoverished farmers, feminists, laborers and resisters of slavery and war.

Such stories are more often recounted in textbooks today; they were not at the time. “Our nation had gone through an awful lot - the Vietnam War, civil rights, Watergate - yet the textbooks offered the same fundamental nationalist glorification of country,” Mr. Zinn recalled in a recent interview with The New York Times. “I got the sense that people were hungry for a different, more honest take.”

(8) Matthew Rothschild, The Progressive (28th January, 2010)

Thank You, Howard Zinn, for being there during the civil rights movement, for teaching at Spelman, for walking the picket lines, and for inspiring such students as Alice Walker and Marian Wright Edelman.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for being there during the Vietnam War, for writing “The Logic of Withdrawal,” and for going to Hanoi.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for always being there.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for being a man who supported the women’s liberation movement, early on.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for being a straight who supported the gay and lesbian rights movement, early on.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for being a Jew who dared to criticize Israel’s oppression of the Palestinians, early on.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for being a great man who didn’t believe in the “Great Man Theory of History.”

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for taking the time to write your landmark work, “A People’s History of the United States,” and for educating two generations now in the radical history of this country, a history, as you stressed, of class conflict.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for grasping the importance of transforming this book into “The People Speak,” the History Channel special that ran in December and that should be used by secondary, high school and college classes for as long as U.S. history is taught.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for opposing war, all wars, including our own “good wars,” our own “holy wars,” as you called them - and for pointing out that a “just cause” does not lead to a “just war.”

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for pointing out that soldiers don’t die for their country, but that they die for their political leaders who dupe them or conscript them into wars. And that they die for the corporations that profit from war.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for urging us to “renounce nationalism and all its symbols: its flags, its pledges of allegiance, its anthems, its insistence in song that God must single out America to be blessed. We need to assert our allegiance to the human race, and not to any one nation.”

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for stressing that change comes from below, and that it comes at surprising times, even when things seem bleakest, if we organize to make it happen.

Thank you, Howard Zinn, for stressing the value of engaging in action to make this world a better place, even if we don’t get there.

(9) Los Angeles Times (28th January 2010)

Howard Zinn, an author, teacher and political activist whose leftist "A People's History of the United States" became a million-selling alternative to mainstream texts and a favorite of such celebrities as Bruce Springsteen and Ben Affleck, died Wednesday. He was 87.

Zinn died of a heart attack in Santa Monica, Calif., daughter Myla Kabat-Zinn said. The historian was a resident of Auburndale, Mass.

Published in 1980 with little promotion and a first printing of 5,000, "A People's History" was - fittingly - a people's best-seller, attracting a wide audience through word of mouth and reaching 1 million sales in 2003. Although Zinn was writing for a general readership, his book was taught in high schools and colleges throughout the country, and numerous companion editions were published, including "Voices of a People's History," a volume for young people and a graphic novel...

At a time when few politicians dared even call themselves liberal, "A People's History" told an openly left-wing story. Zinn charged Christopher Columbus and other explorers with genocide, picked apart presidents from Andrew Jackson to Franklin D. Roosevelt and celebrated workers, feminists and war resisters.

Even liberal historians were uneasy with Zinn. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. once said: "I know he regards me as a dangerous reactionary. And I don't take him very seriously. He's a polemicist, not a historian."

"He taught me how valuable - how necessary dissent was to democracy and to America itself," Ben Affleck said in a statement. "He taught that history was made by the everyman, not the elites. I was lucky enough to know him personally and I will carry with me what I learned from him - and try to impart it to my own children - in his memory."

Oliver Stone was a fan, as well as Springsteen, whose bleak "Nebraska" album was inspired in part by "A People's History." The book was the basis of a 2007 documentary, "Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind," and even showed up on "The Sopranos," in the hand of Tony's son, A.J.

Zinn himself was an impressive-looking man, tall and rugged with wavy hair. An experienced public speaker, he was modest and engaging in person, more interested in persuasion than in confrontation...

One of Zinn's last public writings was a brief essay, published last week in The Nation, about the first year of the Obama administration.

"I've been searching hard for a highlight," he wrote, adding that he wasn't disappointed because he never expected a lot from Obama.

"I think people are dazzled by Obama's rhetoric, and that people ought to begin to understand that Obama is going to be a mediocre president — which means, in our time, a dangerous president — unless there is some national movement to push him in a better direction."

Zinn's longtime wife and collaborator, Roslyn, died in 2008. They had two children, Myla and Jeff.

(10) Godfrey Hodgson, The Guardian (29th January 2010)

Zinn always said he was not a pacifist, because he thought it was too absolute a position. But he was a passionate and highly articulate critic of the wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. As a bombardier during the second world war, he was involved in the first use of napalm as a weapon, and could never quite forgive himself for what he regarded as a crime against German soldiers, as well as French civilians.

Zinn's parents were Jewish immigrants to the US, with very limited education, who settled in Brooklyn, New York, and worked in factories. His father came from Austria-Hungary and his mother from Irkutsk in Siberia. There were no books in the house when he was growing up, until his father bought him a 25-cent edition of the works of Dickens, an offer from an evening newspaper.

Zinn worked in a shipyard after high school and was involved in demonstrations against fascism in the 1930s. He joined the US Army Air Force and during the war, flew from bases in England over France, Germany and his father's native Hungary. The napalm incident, involving petroleum jelly that causes terrible burns, was over Royan in western France.

After the war, he went back to interview victims of the bombing, and later wrote about it in two books. His own experience and his subsequent interviews led him to conclude that the bombing had been ordered more to enhance the careers of senior officers than for any military imperative, and he later wrote about the ethics of bombing in the context of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Tokyo and Dresden, as well as Iraq.