Conscription and the First World War

Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. Over 750,000 had enlisted by the end of September, 1914. Thereafter the average ran at 125,000 men a month until the summer of 1915 when numbers joining up began to slow down. Leo Amery, the MP for Birmingham Sparkbrook pointed out: "Every effort was made to whip up the flagging recruiting campaign. Immense sums were spent on covering all the walls and hoardings of the United Kingdom with posters, melodramatic, jocose or frankly commercial... The continuous urgency from above for better recruiting returns... led to an ever-increasing acceptance of men unfit for military work... Throughout 1915 the nominal totals of the Army were swelled by the maintenance of some 200,000 men absolutely useless for any conceivable military purpose." (1)

The British had suffered high casualties at the Marne (12,733), Ypres (75,000), Gallipoli (205,000), Artois (50,000) and Loos (50,000). The British Army found it difficult to replace these men. In May 1915 135,000 men volunteered, but for August the figure was 95,000, and for September 71,000. Asquith appointed a Cabinet Committee to consider the recruitment problem. Testifying before the Committee, Lloyd George commented: "I would say that every man and woman was bound to render the services that the State they could best render. I do not believe you will go through this war without doing it in the end; in fact, I am perfectly certain that you will have to come to it." (2)

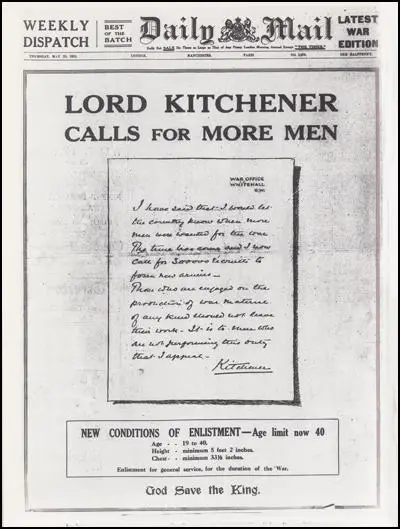

Daily Mail Campaign for Conscription

The shortage of recruits became so bad that George V was asked to make an appeal: "At this grave moment in the struggle between my people and a highly-organized enemy, who has transgressed the laws of nations and changed the ordinance that binds civilized Europe together, I appeal to you. I rejoice in my Empire's effort, and I feel pride in the voluntary response from my subjects all over the world who have sacrificed home, fortune, and life itself, in order that another may not inherit the free Empire which their ancestors and mine have built. I ask you to make good these sacrifices. The end is not in sight. More men and yet more are wanted to keep my armies in the field, and through them to secure victory and enduring peace.... I ask you, men of all classes, to come forward voluntarily, and take your share in the fight". (3)

Lord Northcliffe, the press baron, now began to advocate conscription (compulsory enrollment). On 16th August, 1915, the Daily Mail published a "Manifesto" in support of national service. (4) The Conservative Party agreed with Lord Northcliffe about conscription but most members of the Liberal Party and the Labour Party were opposed to the idea on moral grounds. Some military leaders objected because they had a "low opinion of reluctant warriors". (5)

C. P. Scott, the editor of The Manchester Guardian, was opposed to conscription, for practical reasons. He explained to Arthur Balfour: "You know that I was honestly willing to accept compulsory military service, provided that the voluntary system had first been tried out, and had failed to supply the men needed and who could still be spared from industry, and were numerically worth troubling about. Those, I think, are not unreasonable conditions, and I thought that in the conversation I had with you last September you agreed with them. I cannot feel that they had been fulfilled, and I do feel very strongly that compulsion is now being forced upon us without proof shown of its necessity, and I resent this the more deeply because it seems to me in the nature of a breach of faith with those who, like myself - there are plenty of them - were prepared to make great sacrifices of feeling and conviction in order to maintain the national unity and secure every condition needed for winning the war." (6)

Margaret Bondfield was opposed to the idea as she thought it would influence the military tactics used in the war: "One of the great scandals of the First World War was the attitude of mind (an old one coming down from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) which regarded human life as the cheapest thing to expend. The whole war was fought on the principle of using up man-power. Tanks and similar mechanical help were received with hesitation and repugnance by commanders, and were inadequately used. But man-power, the lives of men, were used with freedom." (7)

This view was expressed in a pamphlet published by the Independent Labour Party: "The armed forces of the nation have been multiplied at least five-fold since the war began, and recruits are still being enrolled well over 2,000,000 of its breadwinners to the new armies, and Lord Kitchener and Mr. Asquith have both repeatedly assured the public that the response to the appeal for recruits have been highly gratifying and has exceeded all expectations. What the conscriptionists want, however, is not recruits, but a system of conscription that will bring the whole male working-class population under the military control of the ruling classes." (8)

No-Conscription Fellowship

Fenner Brockway and his wife Lilla Brockway were both opposed to the First World War and over the first few weeks of the conflict exchanged letters through Sweden with Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin and Karl Liebknecht where they discussed the failure of the Second International to prevent a European war. (9)

Brockway feared the introduction of conscription. On 12th November, 1914, the newspaper published a letter from Lilla that suggested an organisation that was "open to all men of enlistment age who will refuse to bear arms in the event of conscription." Women could be associate members of the proposed organisation. (10) There was a great response to the letter and 150 people joined the organisation, the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF) in the first six days. (11) Lilla became the honorary Secretary of the NCF, until early in 1915 when an office was opened in London to handle the growing membership. (12) By October 1915 it claimed 5,000 members. (13)

Members of the NCF included Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, C. E. M. Joad, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Duncan Grant, Wilfred Wellock, Herbert Morrison, Maude Royden, Ramsay MacDonald, Rev. John Clifford, Helena Swanwick, Catherine Marshall, Kathleen Courtney, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Catherine Marshall, Alfred Mason, Winnie Mason, Alice Wheeldon, William Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Hettie Wheeldon, Storm Jameson, Ada Salter, and Max Plowman. (14)

Clifford Allen, the manager of the first Labour Party daily newspaper, the Daily Citizen and the author of the pamphlet, Is Germany Right and England Wrong? (1914) where he argued against Britain becoming involved in an European war, joined the NCF. "We have got to face the only possible outcome of our Socialist faith - I mean the question of non-resistance to armed force. Don't let us deceive ourselves. The sacredness of human lifeis the mainspring of all our propaganda. In my opinion there can be no two kinds of murder." (15) Allen was elected as chairman of the NCF and Brockway became secretary of the organisation. (16)

Allen explained the purpose of the No-Conscription Fellowship: "As soon as the danger of conscription became imminent, and the Fellowship something more than an informal gathering, it was necessary for those responsible to consider what should be the basis upon which the organization should be built. The conscription controversy has been waged by many people who, by reason of age or sex, would never be subject to the provisions of a Conscription Act. The chief characteristic of the Fellowship is that full membership is strictly confined to those men who would be subject to the provisions of any such Act." (17)

Brockway developed a good relationship with Allen: "I was fascinated by Allen. In physique he was frail and his charm had an almost feminine quality, but never had I met a man with a keener brain, or more confident decision. He was tall, slight and bent of shoulder; his features were clear-cut and classic, but his skin was delicate like that of a child; his shining brown hair was waved, his large brown eyes had sympathy in them and also a suggestion of suffering. His voice was rich and deep, surprisingly so far such a slight physique... I recognised him at once as a potential leader; his personality was so dominating, his mind so clear." (18)

In December 1914 Lilla Brockway joined forces with Emily Hobhouse, Margaret Bondfield, Helena Swanwick, Maude Royden, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Ada Salter, Isabella Ford, Elsie Duval Franklin and Marion Phillips to write an open letter to the women of Germany and Austria. "Some of us wish to send you a word at this sad Christmastide… Though our sons are sent to slay each other, and our hearts are torn by the cruelty of this fate, yet through pain supreme we will be true to our common womanhood. We will let no bitterness enter in this tragedy, made sacred by the life-blood of our best, nor mar with hate the heroism of their sacrifice. Though much has been done on all sides you will, as deeply as ourselves, deplore, shall we not steadily refuse to give credence to those false tales so freely told us, each of the other? Do you not feel with us that the vast slaughter in our opposing armies is a stain on civilisation and Christianity and that still deeper horror is aroused at the thought of those innocent victims, the countless women, children, babes, old and sick, pursued by famine, disease, and death in the devastated areas, both East and West? Peace on earth is gone, but by renewal of our faith that it still reigns at the heart of things. Christmas should strengthen both you and us and all womanhood to strive for its return." (19)

Military Service Bill

H. H. Asquith, the prime minister, "did not oppose it (conscription) on principle, though he was certainly not drawn to it temperamentally and had intellectual doubts about its necessity." David Lloyd George had originally had doubts about the measure but by 1915 "he was convinced that the voluntary system of recruitment had served its turn and must give way to compulsion". (20) Asquith told Maurice Hankey that he believed that "Lloyd George is out to break the government on conscription if he can." (21)

Lloyd George threatened to resign if Asquith did not introduce conscription. Eventually he gave in and the Military Service Bill was introduced by Asquith on 21st January 1916. John Simon, the Home Secretary, resigned and so did Arthur Henderson, who had represented the Labour Party in the coalition government. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of the Daily News argued that Lloyd George was engineering the conscription crisis in order to substitute himself for Asquith as leader of the country." (22)

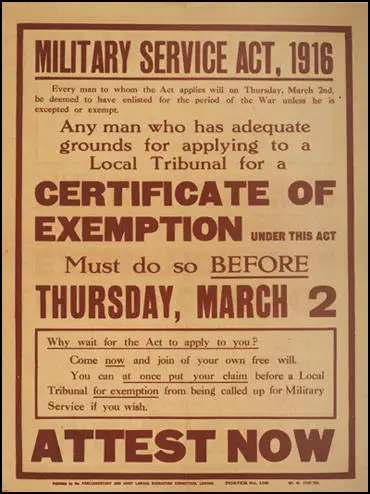

The Military Service Act specified that single men between the ages of 18 and 41 were liable to be called-up for military service unless they were widowed with children or ministers of religion. Conscription started on 2nd March 1916. The act was extended to married men on 25th May 1916. The law went through several changes before the war's end with the age limit eventually being raised to 51.

Lord Northcliffe received a large number of threatening letters because of his compulsion campaign. Tom Clarke, who worked for Northcliffe, saw the contents of these letters, commented that one said: "Warning to Lord Northcliffe... If the compulsion Bill is passed you are a dead man. I and another half-dozen young men have made a pledge - that is, to shoot you like a dog. We know where to find you." (23)

David Lloyd George and Conscription

In a speech he made in Conwy Lloyd George denied that he was involved in any plot against Asquith: "I have worked with him for ten years. I have served under him for eight years. If we had not worked harmoniously - and we have - let me tell you here at once that it would have been my fault and not his. I have never worked with anyone who could be more considerate... But we have had our differences. Good heavens, of what use would I have been if I had not differed from him? Freedom of speech is essential everywhere, but there is one place where it is vital, and that is in the Council Chamber of the nation. The councillor who professes to agree with everything that falls from the leader betrays him."

Lloyd George then went on to suggest that Asquith had reluctantly supported conscription, whereas to him, it was vitally important if Britain was going to win the war. "You must organise effort when a nation is in peril. You cannot run a war as you would run a Sunday school treat, where one man voluntarily brings the buns, another supplies the tea, one brings the kettle, one looks after the boiling, another takes round the tea-cups, some contribute in cash, and a good many lounge about and just make the best of what is going on. You cannot run a war like that." He said he was in favour of compulsory enlistment, in the same way as he was "for compulsory taxes or for compulsory education." (24)

Robert Graves, who was home on leave from the Western Front at the time, was in the audience. "The power of his rhetoric amazed me. The substance of the speech might be commonplace, idle, and false, but I had to fight hard against abandoning myself with the rest of his audience. He sucked power from his listeners and spurted it back at them. Afterwards, my father introduced me to Lloyd George, and when I looked closely at his eyes they seemed like those of a sleep walker." (25)

A. J. P. Taylor has argued that Lord Northcliffe and Lloyd George reflected the mood of the British people in 1916: "Popular feeling wanted some dramatic action. The agitation crystallized around the demand for compulsory military service. This was a political gesture, not a response to practical need. The army had more men than it could equip, and voluntary recruitment would more than fill the gap, at any rate until the end of 1916... Instead of unearthing 650,000 slackers, compulsion produced 748,587 new claims to exemption, most of them valid... In the first six months of conscription the average monthly enlistment was not much above 40,000 - less than half the rate under the voluntary system." (26)

According to the editor of the News Desk at the Daily Mail: "It seemed to us at this time that Northcliffe had attained a position of extraordinary power in the land. Although one never heard him boasting, his bearing suggested that he believed he had saved England from the follies of incompetent government... His campaigns up to date had certainly met with remarkable success. He had scored his first hit by getting Kitchener at the War Office. He had said racing must be stopped, and it was. He had said the shell scandal must be put right by the formation of a Ministry, and the Munitions Ministry was formed under Lloyd George... He had said single men must go first, and it was so. He had demanded a smaller Cabinet to get on with the war, and a special War Council of the Cabinet had been set up... And now he had got compulsion." (27)

It has been argued that enforced enlistment was more to do with employment circumstances, familial circumstances, physical fitness, skills and aptitudes and, to a much lesser extent religious and political grounds. This was vetted very closely by the Tribunals who had to assess a man's fitness for military service and weigh that against his usefulness to the domestic economy. As one historian has pointed out: "a farm lad, aged 19, might have escaped call-up in one part of the country whereas a 40-year old brickie from another part may have been drafted."

Consequences of Conscription

Conscription caused real hardships for the British people. For example, in November 1917 a widow asked Croydon Military Tribunal to let her keep her eleventh son, to look after her. The other ten were all serving in the British armed forces. A man from Barking asked for his ninth son to be exempted as his eight other sons were already in the British Army. The man's son was given three months exemption.

The East Grinstead Observer reported in March, 1916: "John Johnson, a stockman of Belle View Farm, Tilgate, Crawley, shot himself on Friday evening. A gun shot was heard outside John Johnson's home on his birthday and the deceased was found under a yew tree. The poor fellow had placed the barrel of the gun in his mouth, the bullet penetrating the brain and emerging at the top of the skull. It transpired that one of John Johnson's sons had just be killed and another badly wounded in the war. The third son was being called up shortly. "This is the last blow" he was heard to say, "we have sacrificed two, and that ought to be enough." (28)

About 16,000 men refused to fight and these were called conscientious objectors. Most of these men were pacifists, who believed that even during wartime it was wrong to kill another human being. About 7,000 pacifists agreed to perform non-combat service. This usually involved working as stretcher-bearers in the front-line, an occupation that had a very high casualty-rate. Over 1,500 men refused all compulsory service. These men were called absolutists and were usually drafted into military units and if they refused to obey the order of an officer, they were court-martialled.

Forty-one absolutists were transferred to France. These men were considered to be on active service and could now be sentenced to death for refusing orders. Others were sentenced to Field Punishment Number One. (29) Those found guilty before being transferred to France were sent to English prisons. Conditions were made very hard for the conscientious objectors and during the war and sixty-nine of them died in prison. (30)

Primary Sources

(1) King George V, statement issued on 11th October, 1915.

At this grave moment in the struggle between my people and a highly-organized enemy, who has transgressed the laws of nations and changed the ordinance that binds civilized Europe together, I appeal to you.

I rejoice in my Empire's effort, and I feel pride in the voluntary response from my subjects all over the world who have sacrificed home, fortune, and life itself, in order that another may not inherit the free Empire wnich their ancestors and mine have built.

I ask you to make good these sacrifices.

The end is not in sight. More men and yet more are wanted to keep my armies in the field, and through them to secure victory and enduring peace.

In ancient days the darkest moment has ever produced in men of our race the sternest resolve.

I ask you, men of all classes, to come forward voluntarily, and take your share in the fight.

In freely responding to my appeal you will be giving your support to our brothers who, for long months, have nobly upheld Britain's past traditions and the glory of her arms.

(2) The Great World War: Volume VI (1918)

The total response to Lord Derby's appeal proved, numerically, enormously large. Upwards of 2,800,000 men offered themselves, this in itself being a fine tribute to the old voluntary system. But when the figures came to be analysed, and the men themselves to be examined, the total number available for service was disappointing. Our national task involved far more than the maintenance of new armies in all parts of the world. There was the navy - the greatest navy the world had ever known - and there were munitions not only for ourselves but also for our Allies. There was also the vital need to sustain food-supplies and national credit, as well, also, to a large extent, the credit of the Allied Powers: and all this hinged largely on the export trade from this country, which demanded a vast amount of industrial labour. Hence the need for exemptions and the establishment of tribunals all over the country to consider the appeals both of masters and men. Women came to the rescue by the hundred thousand, and proved excellent workers; but even when this fact and the help of all other kinds of unskilled labour were taken into account, it was impossible in a complex society like ours, with its worldwide responsibilities, to put all our able-bodied men into the fighting services.

The very number and scale of the exempted men made conscription inevitable. The man in the street, where so much was held from his knowledge in a war over which the veil of secrecy was drawn more tightly every month, sometimes had cause to complain of the inequality in the treatment of individuals. Parents and relations especially, as Lord Derby pointed out in his report, could not understand why their sons, husbands, or brothers should join while other young men held back and secured lucrative employment. Also, the system of submitting cases to tribunals was viewed with distrust from the first. It was new; it involved the disclosure of private affairs; and it led to a fear that cases might not be fairly and impartially dealt with. Conscription, therefore, could only have been a matter of time, even if the proportion of single men attested under the Derby Scheme had been sufficient to cover the Prime Minister's pledge. In point of fact it was not sufficient, a total of 651,160 unstarred single men remaining unaccounted for. This, as Lord Kitchener, Lord Derby, and the Prime Minister alike agreed, was far from being a negligible quantity, and in order to redeem the pledge it was not possible to hold married men to their attestation until the services of single men had been obtained by other means.

The only remaining possibility was national service, which brought about something approaching equality of sacrifice, and marked a definite stage in the complete organization of the country for war. Lord Derby's canvass showed very distinctly that it was not lack of courage that was keeping some men back. Nor was there, he wrote at the close of his report on December 12, 1915, the slightest sign but that the country as a whole was as determined as ever to support the Prime Minister in the pledge which he made at the Guildhall three months after the outbreak of the war - to the effect that we would fight to the last until Germany's military power was fully destroyed.

(3) C. P. Scott, letter to Arthur Balfour about the threaten introduction of military conscription (2nd January, 1916)

You know that I was honestly willing to accept compulsory military service, provided that the voluntary system had first been tried out, and had failed to supply the men needed and who could still be spared from industry, and were numerically worth troubling about. Those, I think, are not unreasonable conditions, and I thought that in the conversation I had with you last September you agreed with them. I cannot feel that they had been fulfilled, and I do feel very strongly that compulsion is now being forced upon us without proof shown of its necessity, and I resent this the more deeply because it seems to me in the nature of a breach of faith with those who, like myself - there are plenty of them - were prepared to make great sacrifices of feeling and conviction in order to maintain the national unity and secure every condition needed for winning the war.

(4) Charles Repington, diary entries (January 1916)

Wednesday, January 5th: Went down to hear the P.M (Asquith) bring in the Compulsion Bill. Had a seat under the clock in the Sergeant-at-Arms' box. A packed house. The P.M. very quiet and undemonstrative. He spoke so low that he was invited to speak up. A great want of magnetism, and judged by this speech his powers are failing, but it may be only a trick. He gave no explanations of the military necessity for the Bill, but restricted himself to the political side, to his pledge, and to the terms of his Bill. Sir John Simon, who has happily left the Government, got up next and made an unhappy speech for a Minister who has had all the facts before him. He was cheered by the riff-raff of the Left, but he made a bad impression.

Thursday, January 6th: The Bill passes first reading, majority 298. Bonar Law, Ward, Barnes, Samuel, and Balfour made the most effective speeches. The Labour Conference passes a resolution by a supposed large majority against Compulsion.

(5) Margaret Bondfield, A Life's Work (1950)

In January a special National Conference urged the Labour Members of Parliament to oppose conscription. When it met, the Annual Conference condemned conscription but declined by a small majority to demand the repeal of the Act which had just been passed, setting up Conscription for the first time in modern English practice.

The Conscription Act was passed within a few months of the opening of the great military offensive of 1916, which revealed to the world the appalling scale of the losses that the nation would have to endure. One of the great scandals of the First World War was the attitude of mind (an old one coming down from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) which regarded human life as the cheapest thing to expend. The whole war was fought on the principle of using up man-power. Tanks and similar mechanical help were received with hesitation and repugnance by commanders, and were inadequately used. But man-power, the lives of men, were used with freedom.

(6) The Independent Labour Party was opposed to conscription. It published a pamphlet Appeal to Organised Workers on the subject in 1916.

The armed forces of the nation have been multiplied at least five-fold since the war began, and recruits are still being enrolled well over 2,000,000 of its breadwinners to the new armies, and Lord Kitchener and Mr. Asquith have both repeatedly assured the public that the response to the appeal for recruits have been highly gratifying and has exceeded all expectations. What the conscriptionists want, however, is not recruits, but a system of conscription that will bring the whole male working-class population under the military control of the ruling classes.

(7) The East Grinstead Observer (25th March, 1916)

John Johnson, a stockman of Belle View Farm, Tilgate, Crawley, shot himself on Friday evening. A gun shot was heard outside John Johnson's home on his birthday and the deceased was found under a yew tree. The poor fellow had placed the barrel of the gun in his mouth, the bullet penetrating the brain and emerging at the top of the skull. It transpired that one of John Johnson's sons had just be killed and another badly wounded in the war. The third son was being called up shortly. "This is the last blow" he was heard to say, "we have sacrificed two, and that ought to be enough."

(8) King George V, statement issued on 25th May 1916.

To enable our country to organise more effectively its military resources in the present great struggle for the cause of civilisation, I have, acting on the advice of my Ministers, deemed it necessary to enrol every able-bodied man between the ages of eighteen and forty-one.

I desire to take this opportunity of expressing to my people my recognition and appreciation of the splendid patriotism and self-sacrifice which they have displayed in raising by voluntary enlistment since the commencement of the War, no less than 5,041,000 men, an effort far surpassing that of any other nation in similar circumstances recorded in history, and one which will be a lasting source of pride to future generations. I am confident that the magnificent spirit which has hitherto sustained my people through the trials of this terrible war will inspire them to endure the additional sacrifice now imposed upon them, and that it will, with God's help, lead us and our Allies to a victory which shall achieve the liberation of Europe.

(9) Victor Morris, a 38 year old shopkeeper, appeared before a Military Tribunal on 28th October, 1916. Victor Morris told the Tribunal that he was refusing to join the army because he was a pacifist. Morris was cross-examined by Alexander Johnson, a tailor, and Wallace Hills, editor of the local newspaper.

Victor Morris: I believe that God alone has the right to take life and that under no circumstances whatever has a man the right to kill another person. I believe that war is immoral.

Wallace Hills: You object to taking life; do you not think it is your duty to do all can to prevent our enemies from taking our lives?

Victor Morris: Not by organised murder, for that is what war is.

Alexander Johnson: Do you mean to say that my son, who has gone out to fight for such as you, is a murderer? You ought to be ashamed of yourself.

Wallace Hills: Do you say force is un-Christian? Do you object to force being applied to criminals.

Victor Morris: When a policeman goes to arrest a man he does not first knock him down with his truncheon.

Alexander Johnson: I always looked upon you as a particular pugnacious individual and one who I should not like to upset.

Victor Morris: That is a very false estimate of my character.

Wallace Hills: Was that not a little pugnacity about you when you publicly lectured that scoutmaster on Littlehampton Railway Station because of his "sin" of training boys in military work?

Victor Morris: Well it required some moral courage.

Wallace Hills: Application for exemption is refused.

(10) Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Fate Has Been Kind (1942)

It was not until the middle of 1918 that my age group came within the Conscription Act and I was called up. I was then 46. Believing as I did that the war could and should be brought to an end by a negotiated peace, I could not very well go out to fight for Mr. Lloyd-George's 'knock-out blow'. I accordingly went before a tribunal in Dorking as a conscientious objector. The Clerk to the Council told the tribunal that he knew I had held my views for a considerable time, and the military representative said that he did not particularly 'want this man'. So I was awarded exemption, conditional on my doing work of national importance, and work on the land was indicated.

(11) After Raymond Postgate was sent to prison for refusing to be conscripted, his sister, Margaret Postgate, became involved in the Peace Movement.

In the spring of 1916 Ray, a scholar in his first year at St. John's College, Oxford, was called up. Of course he refused to go, thereby reducing his father to apoplectic fury; and, after he had failed to secure exemption and was brought before the magistrates as a mutinous soldier, I went up to Oxford be by his side. At that date it needed a fair amount of courage to be a C.O. Though the Military Service Act allowed exemption on grounds of conscience, it was regrettably vague in its definition of either "conscience" or "exemption"; and the decision as to whether a man had or had not a valid conscientious objection, and if he had, whether he was to be exempted from all forms of war service or from combatant service only, or something between the two, was left to local tribunals all over the country, who had no common standard or guidance, and generally - though not by any means invariably - took the view that every fit man ought to want to fight, and that anyone who did not was a coward, an idiot, or a pervert, or all three.

Objection on religious grounds was for most part treated with respect, particularly if the sect had a respectable parentage; Quakers usually came off lightly, and were permitted to take up any form of service they felt able to do; though Quakers who were "absolutists," i.e., who refused to aid the war effort in any way whatever, were apt to be jailed after a long and futile cross-examination by the Tribunal on how they would behave if they found a German violating their mother. But non-Christians who objected on the grounds that they were internationalists or Socialists were obvious traitors in addition to all their other vices, and could expect little mercy. They would be sent to barracks, and thence to prison - and then nobody quite knew what would happen to them. There was talk of despatching them to France, unarmed, and shooting them there for mutiny.

It is almost literally true that when I walked away from the Oxford court-room I walked into a new world, a world of doubters and protesters, and into a new war - this time against the ruling classes and the government which represented them, and with the working classes, the Trade Unionists, the Irish rebels of Easter Week, and all those who resisted their governments or other governments which held them down. I found in a few months the whole lot which Henry Nevinson used to call "the stage-army of the Good" - the ILP, the Union of Democratic Control, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Daily Herald League, the National Council of Civil Liberties - and, above all, the Guild Socialists and the Fabian, later the Labour Research Department.

(12) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

A large anti-conscription conference was held at the Ethical Society's Hall near Liverpool Street Station, London. There were determined but unsuccessful efforts to break it up. Toughs who had obviously been encouraged to be present fiercely attacked us as we emerged, with the City police doing little or nothing to stop them.

When conscription came into force in 1917 I duly received my call-up notice. Of course, there was no question of my being fit for military service because of my blindness in one eye and it would, I suppose, have been easy to pretend that I wanted to put on uniform and then allow the medical officers to turn me down, but I was intent on sticking to my principles. In due course I was ordered to report before the Conscientious Objectors Tribunal for Wandsworth. Exemption could be absolute; conditional on taking up some form of national service; or refused on the grounds that the applicant had failed to prove the genuine nature of his objection.

There are many stories of the ruthless and sometimes insulting behaviour of the members of these tribunals in the First World War when the standard question to an absolutist (as men who were not willing to help the military machine directly or indirectly were called) was, "What would you do if you came upon a German attempting to rape your sister?". However, my inquisitors were both courteous and fair.

(13) John William Graham, Conscription and Conscience (2010)

In this place, alone, you spend twenty-three hours and ten minutes out of the twenty-four in the first month of your sentence, hungry most of the time. You get little exercise, and probably suffer from indigestion, headache or sleeplessness. The entire weekend is solitary until you attend chapel. After the first month you have thirty minutes exercise on Sunday. You would go mad but for the work. You sit and stitch canvas for mailbags. Your fingers begin by being sore and inflamed, but they become used to it. At first your daily task can hardly be finished in a day. You struggle hard to get the reward of a large mug of sugarless cocoa and a piece of bread at eight o'clock. It will save you from hunger all night, for your previous food - I cannot call it a meal - had been at 4.15. This extra ration, which varied, and was not universal, was a war-time incentive to produce work of national importance. It was cut off as a war economy in 1918.

Except on monthly visits (15 minutes), or if he has to speak to the Chaplain or doctor, or if he has to accost a warder, the prisoner is not allowed to speak for two years the sentence usually given to a conscientious objector.

The punishments for breaking a rule, for talking, for lying on your bed before bedtime, looking out of a window, having a pencil in your possession, not working, and many other such acts were savage. If those things were reported to the Governor, there would be, say, three days bread and water and in a gloomy basement cell, totally devoid of furniture during the daytime. This was famine. In addition, your exercise might be taken away, and your work in association, your letter or visit would be postponed, whilst your family were left wondering what had happened, and marks, with the effect of postponing your final release, would be taken off.

(14) John Taylor Caldwell, Come Dungeons Dark: The Life and Times of Guy Aldred (1988)

The treatment of nineteen-year-old Jack Gray was in blatant defiance of the Order. On 7th May 1917 he arrived at Hornsea Detention Camp. Refusing to put on the uniform he was abused and tormented for the rest of the day. Live ammunition was fired at his feet, his ankles were beaten with a cane, his mouth was split open by a heavy blow from a sergeant. Next day the process was continued. Then his hands were bound firmly behind his back and his ankles tied together. A rope was fastened to his wrists and pulled tight to the ankles. In this position he had to stand for several hours, then a bag of stones was fastened on his back and he was beaten round the training field till he collapsed. There were other brutalities inflicted on Jack which we will not detail, but of such a nature that eight of the soldiers refused to take part, leaving themselves liable to severe penalties.

The torture which broke the boy's resolve was when he was stripped naked and had a rope tied round his waist. He was then thrown into the camp cesspool and pulled around. After the second immersion the rope had so tightened round his waist that he was in great pain. Still the treatment continued "for eight or nine times", said a witness at the subsequent court martial. Someone, transported into ecstasies of sadistic excitement at the sight of the lad's muddy, filth-encrusted body, got an old sack and making holes for arms and head, forced the youngster into it for further grotesque immersions. Then Jack Gray gave in, promising to fight for England and save the world from the barbarity of the Hun.

The local M.P. forced an Enquiry. The officers responsible were censured. Nobody was allowed to see the report of the Enquiry.

The case of James Brightmore was even more outrageous. It certainly got more publicity. Brightmore was a young solicitor's clerk from Manchester. After serving eight months of a twelve months sentence for refusing to put on the uniform, Brightmore was sent to Shore Camp, Cleethorpes. Still refusing, he was sentenced to twenty-eight days solitary confinement on bread and water. According to Army Order X, Brightmore should have been serving his sentence in prison, but the authorities pretended not to know. There was no solitary cell in the camp, so the Major had to improvise, like the efficient soldier he was. He had a deep hole dug in the parade ground, coffin shaped, and into this young Brightmore was inserted. For four days he stood ankle-deep in water, then a piece of wood was lowered for him to stand on, but that sank into the water, which now stank, and in which a dead mouse floated.

One day it rained heavily. Some of the soldiers took him from the hole and put him into a tent where he slept the night. He remained there all the next day, and then the Major became aware of it, and he was roughly wakened and thrust down the hole again, and a black tarpaulin pulled over it to keep out the rain. He was kept there for a week, the Major calling on him during the day to jeer, telling him on one occasion that his friends had been sent to France and shot, and that he would be in the next batch.

One of the soldiers who had been reprimanded for taking Brightmore out of the hole, realising that there was no intention of releasing the youth, tore open a cigarette packet and passed it down with a stub of pencil, suggesting that Brightmore write to his parents. He did so, and the soldier added a covering note, saying that the hole was twelve feet deep. They were under orders not to take any notice of the boy's complaints, but "the torture is turning his head." At that time Brightmore had been in the vertical grave for eleven days.

Brightmore's parents took the letter to the Manchester Guardian, which published it with a strongly worded editorial. Within forty minutes of the paper arriving at the camp, Brightmore had been taken from the hole, which was hastily filled in. The major and a fellow officer were dismissed from their posts for disobeying the Order.

The third case of Court Martial did not involve a young man, but the mature and articulate C.H. Norman, a writer on international politics and founder-member of the No Conscription Fellowship. He came up against the out-spoken sadist Lt. Col. Reginald Brooke, Commandant of Wandsworth Military Detention Camp, who declared that he didn't give a damn for Asquith and his treacherous Government. He would do what he liked with his prisoners.

C.H. Norman thought differently. When he went on hunger strike he was badly beaten, tied to a table and a tube forced up his nose and down into his stomach. Through this, liquid food was poured. Then he was forced into a straitjacket fastened so tightly that breathing was difficult, and he suffered a spell of unconsciousness. He was bound in the jacket for twenty-three hours, during which time the Col, called on him to jeer. Norman was not an inexperienced adolescent: he brought a civil action against the Col., who was court martialled and sentenced to be dismissed from his cherished position where his sadism (for it could have been no less) had free play.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)