Käthe Kollwitz: A German Artist and the First World War

Käthe Kollwitz was a 47 year old artist living in Berlin on the outbreak of the First World War. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28th June, 1914, triggered off the First World War. Käthe's two sons, Hans and Peter, immediately joined the German Army. On 23rd October, 1914, Peter, aged 20, was killed at Dixmuide in Belgium on the Western Front.

Kollwitz found it difficult to use her art to deal with her grief. She wrote in her journal: "Stagnation in my work... When it comes back (the grief) I feel it stripping me physically of all the strength I need for work. Make a drawing: the mother letting her dead son slide into her arms. I might make a hundred such drawings and yet I do not get any closer to him. I am seeking him. As if I had to find him in the work... For work, one must be hard and thrust outside one-self what one has lived through. As soon as I begin to do that, I again feel myself a mother who will not give up her sorrow. Sometimes it all becomes so terribly difficult."

Primary Sources

(Source 1) Käthe Kollwitz, diary entry (30th September, 1914)

Nothing is real but the frightfulness of this state, which we almost grow used to. In such times it seems so stupid that the boys must go to war. The whole thing is so ghastly and insane. Occasionally there comes that foolish thought: how can they possibly take part in such madness? And at once the cold shower: they must, must!

(Source 3) Käthe Kollwitz, diary entry (30th December, 1914)

My Peter, I intend to try to be faithful.... What does that mean? To love my country in my own way as you loved it in your way. And to make this love work. To look at the young people and be faithful to them. Besides that I shall do my work, the same work, my child, which you were denied. I want to honor God in my work, too, which means I want to be honest, true, and sincere.... When I try to be like that, dear Peter, I ask you then to be around me, help me, show yourself to me. I know you are there, but I see you only vaguely, as if you were shrouded in mist. Stay with me.... my love is different from the one which cries and worries and yearns.... But I pray that I can feel you so close to me that I will be able to make your spirit.

(Source 5) Käthe Kollwitz, letter to Vorwarts (October, 1918)

In the Vorwaerts of October 22 Richard Dehmel published a manifesto entitled Sole Salvation. He appeals to all fit men to volunteer. If the highest defense authorities issued a call, he thinks, after the elimination of the "poltroons" a small and therefore more select band of men ready for death would volunteer, and this band could save Germany's honor.

I herewith wish to take issue with Richard Dehmel's statement. I agree with his assumption that such an appeal to honor would probably rally together a select band. And once more, as in the fall of 1914, it would consist mainly of Germany's youth - what is left of them. The result would most probably be that these young men who are ready for sacrifice would in fact be sacrificed. We have had four years of daily bloodletting - all that is needed is for one more group to offer itself up, and Germany will be bled to death. All the country would have left would be, by Dehmel's own admission, men who are no longer the flower of Germany. For the best men would lie dead on the battlefields. In my opinion such a loss would be worse and more irreplaceable for Germany than the loss of whole provinces...

I respect the act of Richard Dehmel in once more volunteering for the front, just as I respect his having volunteered in the fall of 1914. But it must not be forgotten that Dehmel has already lived the best part of his life. What he had to give - things of great beauty and worth - he has given. A world war did not drain his blood when he was twenty.

But what about the countless thousands who also had much to give - other things beside their bare young lives? That these young men whose lives were just beginning should be thrown into the war to die by legions - can this really be justified?

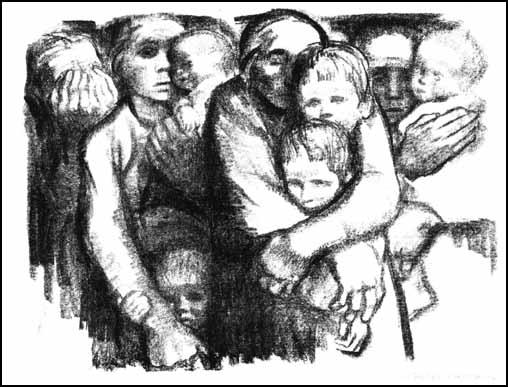

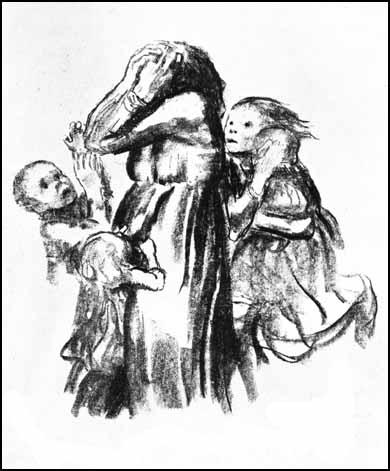

(Source 6) Martha Kearns, Käthe Kollwitz (1976)

The influence of her mother upon Käthe's character and work had been profound. Like her mother - and like herself - the women Kollwitz portrayed are loving and strong. It is the women in her work-most often mothers - who carry the drama. With few exceptions, men participate in Kollwitz' emotional scene as adjuncts, as fathers and husbands in the background. It is the women who confront the crises head on: they brave war, poverty, homelessness, their husband's unemployment, servitude, widowhood, sexual abuse, and their children's hunger. In the darkest despair, the women continue to support the life of others. Kollwitz's women are subjected but not humiliated, victimized by force but not weak; they have the power - through strong love - to face and endure their trials. Her women are heroic in the epic of every day.

(Source 8) Käthe Kollwitz, journal entry (June, 1926)

The cemetery is close to the highway.... The entrance is nothing but an opening in the hedge that surrounds the entire field. It was blocked by barbed wire which a friendly young man bent aside for us; then he left us alone. What an impression: cross upon cross.... on most of the graves there were low, yellow wooden crosses. A small metal plaque in the center gives the name and number. So we found our grave.... We cut three tiny roses from a flowering wild briar and placed them on the ground beside the cross. All that is left of him lies there in a row-grave. None of the mounds are separated; there are only the same little crosses placed quite close together.... and almost everywhere is the naked, yellow soil.... at least half the graves bear the inscription unknown German...

We considered where my figures might be placed... What we both thought best was to have the figures just across from the entrance, along the hedge.... Then the kneeling figures would have the whole cemetery before them... Fortunately no decorative figures have been placed in the cemetery, none at all. The general effect is of simple planes and solitude... Everything is quiet, but the larks sing gladly.

As we went on, we probably passed the very place where he fell, but here everything has been rebuilt... Everywhere there are traces of the war.... the ground is hollowed out by countless shellholes... In this place alone the Germans are said to have lost 200,000 men in the course of the four years. Their trenches and the Belgian trenches were sometimes separated by only twenty, even ten yards. They have been closed up now and life goes on; only the Belgian dugouts and trenches, those bowels of death as they call them, have been preserved and are a sort of place of pilgrimage for the Belgians...

The British and Belgian cemeteries seem brighter, in a certain sense more cheerful and cosy, more familiar than the German cemeteries. I prefer the German ones. The war was not a pleasant affair; it isn't seemly to prettify with flowers the mass deaths of all these young men. A war cemetery ought to be somber.

Questions for Students

Question 1: Read source 1. Describe Käthe Kollwitz's attitude towards the war?

Question 2: What does Käthe Kollwitz mean when she says in source 3 that "I intend to try to be faithful"?

Question 3: Study sources 2, 4 and 7. How do these works of art explain her feelings towards the war? You might find it helpful to read source 6.

Question 4: Read source 5. Why does she disagree with Richard Dehmel view on how to "save Germany's honor"?

Question 5: In 1926 Käthe Kollwitz visited the cemetery where her son Peter was buried. Why did she prefer the German cemeteries to the British and Belgian cemeteries?

Answer Commentary

A commentary on these questions can be found here

Download Activity

You can download this activity in a word document here

You can download the answers in a word document here