Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Schmidt, the daughter of Katharina and Karl Schmidt, was born in the industrial city of Königsberg, on 8th July 1867. Her father was a stone mason and house builder, who developed strong socialist opinions after reading the work of Karl Marx. Her mother was the daughter of Julius Rupp, a nonconformist religious leader who suffered much political abuse. (1)

She was a "quiet, shy and nervous" child and spent most of her time with her older siblings, Julie and Konrad: "There were endless places to play and numerous adventures to be had in those yards. For example, a pile of coal had been unloaded from a boat and dumped in the yard in such a way that it sloped up gently and then fell off sharply on the side facing our garden. It was a risky matter to climb up almost to the brink. I myself never dared, but Konrad did. Another boy who tried it was hurt." (2)

Karl Schmidt was educated to become a lawyer but had not followed his profession because his political, social, and moral views made it impossible for him to serve what he considered to be the authoritarian government led by Otto von Bismarck. He joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP). According to Martha Kearns: "Schmidt was a man of the future in his educational as well as political views. Unlike many Prussian fathers... the head of the Schmidt family was not a strict disciplinarian and he did not believe in corporal punishment. A moral idealist, he taught his children to correct their behaviour through self-control, choosing to guide rather than force their development.... In a day when girls were rarely encouraged to aspire to roles other than those of wife and mother, he personally helped to develop the individual talents of each of his three daughters." (3)

Family Life

Käthe was also influenced by her grandfather who also held strong socialist beliefs and had been imprisoned because his religious views differed from those of Fredrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia. She later recalled: "He was always ready to give, was always kindly and informative, and often laconically humorous... He was tall, thin, dressed in black up to his chin, his eye-glasses having a faintly bluish tinge, his blind eye covered by a somewhat more opaque glass." (4)

Käthe greatly admired her grandfather: "I respected him, but was timid in his presence because I was a bashful child. I did not have the personal relationship with him which my two older sisters and, above all, my brother experienced. Along with the other children of the congregation I had religious instruction under him, an instruction which perhaps passed over the heads of most of the children, myself included. The teaching consisted of religious history, discussion of the gospels, and commentary on the Sunday sermon. A loving God was never brought home to us." (5)

It was very important to Karl Schmidt that his children grew up with a sympathy for the plight of the working-class. Käthe remembers her father reading the poem, The Song of the Shirt, written by the English poet, Thomas Hood. Käthe later explained that as her father "read the last lines, he became so moved that his voice grew fainter and fainter until he was unable to finish. His silent identification with the poor seamstress filled the room. In the silence Käthe, too, experienced the sweat, heat, and grind of a shirt factory and the working woman's numb fatigue." (6)

All three girls were gifted artists. The youngest daughter, Lise, was especially talented. One day Käthe overheard her father tell her mother that Lise's drawings were so good that she would "soon be catching up to Käthe". She wrote in her diary: "When I heard this I felt envy and jealously for probably the first time in my life. I loved Lise dearly. we were very close to one another and I was happy to see her progress up to the point where I began; but everything in me protested against her going beyond that point. I always had to be ahead of her." (7)

Her father became convinced that Käthe could become a great artist. In 1881 he arranged for her to have lessons with Rudolf Mauer, a local copper engraver. Käthe made drawings from plaster casts and copied drawings by famous artists. Käthe later recalled that her father and grandfather, Julius Rupp, were both important to her development: "Although I thought that Grandfather's religious force did not live on in me, a deep respect remained, a respect for his teachings, his personality and all the Congregation stood for. I might say that in recent years I have felt both Grandfather and Father within myself, as my origins. Father was nearest to me because he had been my guide to socialism, in the sense of the longed-for brotherhood of men." He once told her: "Man is not here to be happy, but to do his duty".Her grandfather died in 1884. (8)

The Schmidt family involvement with the Social Democratic Party (SDP) enabled Käthe to meet another young member, Karl Kollwitz. He was an orphan who lived with a family in Konigsberg. Like her father he was passionately interested in politics and introduced her to the writings of August Bebel. This included his pioneering work, Woman and Socialism (1879). In the book Bebel argued that it was the goal of socialists "not only to achieve equality of men and women under the present social order, which constitutes the sole aim of the bourgeois women's movement, but to go far beyond this and to remove all barriers that make one human being dependent upon another, which includes the dependence of one sex upon another." (9)

Käthe was particularly impressed with one passage of the book that stated: "In the new society women will be entirely independent, both socially and economically... The development of our social life demands the release of woman from her narrow sphere of domestic life, and her full participation in public life and the missions of civilisation." Bebel also predicted the dissolution of marriage, believing that socialism would free women from their second-class status. (10)

At the age of sixteen Käthe tried to enter the Königsberg Academy of Art. However, as a female, her application was rejected and so her father arranged for her to study under the painter, Emil Neide. He introduced her to work of the French artist, Gustave Courbet, who was the leader of the realist movement. Influenced by this attempt to capture the reality of everyday life, she completed The Emigrants, a work that had been inspired by a poem of that name by Ferdinand Freiligrath. (11)

In 1884 Karl Schmidt arranged for Käthe and Lise to visit Berlin. While in the city they stayed with their elder sister, Julie, and her husband. He was a close friend of the young poet and dramatist, Gerhart Hauptmann. He invited Käthe and Lise to a dinner party that was attended by two artists, Hugo Ernst Schmidt and Arno Holz. Hauptman described Käthe as "fresh as a rose in dew, a charming, clever girl, who, because of her extreme modesty, did not speak freely about her calling as an artist but let it be known by her sure, sensitive manner." Käthe was also impressed with Hauptman: "It was an evening that left its mark... a wonderful foretaste of the life which was gradually but irresistibly opening up for me." (12)

Käthe Kollwitz and Karl Stauffer-Bern

Karl Kollwitz became a medical student and in 1884 he asked Käthe to marry him. Her agreement to his proposal upset her father who feared that marriage would inhibit her artistic career. He arranged for her to study at the Berlin School for Women Artists, where she studied under Karl Stauffer-Bern. He introduced her to the work of Max Klinger. Käthe's biographer, Martha Kearns, has pointed out: "She (Käthe) had never heard of Max Klinger, Prussia's most skilled artist of the then-popular naturalism, a school of thought which deemed people to be predetermined victims in a bitter struggle for survival. As an art form, naturalism emphasized photo like images of actual persons, scenes, and conditions, often in the most minute, even microscopic detail. Unlike artists working in other styles, naturalist artists featured women as subjects as frequently as men." (13)

At Stauffer-Bern's suggestion, Käthe went to see Klinger's Ein Leben, at a Berlin exhibition. It was a series of fifteen etchings about a woman who had lost her virginity to her lover and who thus, in the eyes of the bourgeoisie, had "fallen" into unredeemable sin. The series reflected the double standard held against women at the turn of the twentieth century. This extremely accomplished and powerful series inspired Käthe and she wrote in her journal: "It was the first work of his I had seen, and it excited me tremendously." (14)

Käthe became friends with fellow art student, Emma Jeep. As women they were not allowed to attend life-drawing classes (this did not change in Berlin until 1893). At Käthe's request, Jeep often posed nude for her in the privacy of their rooms. The two women became close friends and this relationship lasted for the rest of Käthe life. At the time, Jeep was highly critical of Käthe's decision to get engaged. Jeep was a feminist and believed marriage would damage a woman's career as an artist. (15)

In her journal Käthe admitted that she was attracted to women: "Although my leaning toward the male sex was dominant, I also felt frequently drawn toward my own sex-an inclination which I could not correctly interpret until much later on. As a matter of fact I believe that bisexuality is almost a necessary factor in artistic production; at any rate, the tinge of masculinity within me helped me in my work." (16) Her biographer, Martha Kearns, has pointed out: "It is not known whether she ever acted on her feelings for women, whether she wanted to, or whether she would have been able to, considering her society's prohibitions and her own inhibitions." (17)

Käthe intended to continue her studies with Karl Stauffer-Bern but in 1888, Friedrich Welti, a very wealthy businessman, agreed to finance a stay in Rome for Stauffer-Bern. Soon afterwards, Stauffer-Bern, began a sexual relationship with his wife, Lydia Welti-Escher. When news of the relationship reached Welti, he used his government contacts to have Lydia committed to an asylum, and Stauffer-Bern was briefly sent to prison under trumped-up charges. On his release he committed suicide. (18)

Munich Women's Art School

In 1888 Käthe went to study at the Munich Women's Art School. She also joined the informal Composition Club, that met at the Glücks-Café. Other members included Otto Greiner, Alexander Oppler and Gottlieb Elster. Käthe impressed fellow members when she exhibited for the first time at the club. The drawings were illustrations of a coal miner's strike. That night she wrote in her journal: "For the first time I felt that my hopes were confirmed; I imagined a wonderful future and was so filled with thoughts of glory and happiness that I could not sleep all night." (19)

Käthe and Jeep also joined the Munich Etching Club. Later, Jeep described Käthe's first lesson: "The coal-black plate was now ready for drawing, so she found an empty table to work. Her right hand gripped the etching knife surely as she pressed it into the black wax. The manner in which she etched was much freer and more expressive than what they were used to; her etching looked more like a pen-and-ink drawing. Gradually the copper lines showed the face of an old man... The copper face shone out impressively from the blackened plate; she felt satisfied, and ready to etch... She continued to work industriously. Her style of secure and penetrating lines was already apparent." (20)

Käthe continued to take a keen interest in politics. She was impressed with the work of Karl Kautsky, who was considered the best interpreter of the theories of Karl Marx. She spent a lot of time with fellow artist, Helene Bloch, who had a studio in Königsberg. She recorded in her journal that "we had weekly get-togethers in my studio during which we read Kautsky's popularization of Marx's ideas." (21)

According to the author of Käthe Kollwitz (1976), Käthe gradually began to give up on painting: "By this time she was able to draw with pen, pencil, chalk, and charcoal; paint with ink and wash, and etch; but she could not lift the same scene intact onto canvas. Try as she might to perfect her painterly technique in the same way that she had mastered drawing and etching, she found that she had no feel for color or its great and subtle uses; nor did colour or nature inspire her in the same way as the lines and expressions of working people." (22)

In 1891 Karl Kollwitz qualified as a doctor and obtained a position in a working-class area of Berlin. In a response to the growing support of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), Otto von Bismarck had introduced the first European system of health insurance in which accident, sickness, and old age expenses of the workers and their families were covered by a government health insurance. As a socialist, Karl wanted to serve the poor and this new legislation made this possible. (23)

Karl Kollwitz now asked Käthe to marry him. Käthe recorded in her journal how disappointed her father had been by the news: "He had expected a much faster completion of my studies, and then exhibitions and success. Moreover, as I have mentioned, he was very skeptical about my intention to follow two careers, that of artist and wife." Shortly before her wedding on 13th June, 1891, her father told her, "You have made your choice now. You will scarcely be able to do both things. So be wholly what you have chosen to be." (24)

The couple moved to an apartment on 25 Weissenburger Strasse, on the corner of Wörther Platz. Soon after they married Emma Jeep visited them: "Our attitude toward life was that of a child's: we still expected adventures. At the very first meeting with Käthe's husband, who now belongs to both of us, we laughted and laughed hysterically. We were taken by such a storm of laughter that we barely needed any reason or impulse to start us up again! Dr. Kollwitz was helpless. Finally he diagnosed it - and us - as fatigue, and told us that we should go to sleep. So we retreated to the big double bed, and the unstoppable laughter succumbed, after a while, to our dreams." (25)

At first, Karl attracted very few patients. Käthe recorded: "We often stood at the window or on the tiny corner balcony, watching the passersby in the street below, hoping that one or other of them would find his way into the waiting-room." Next to Karl's office on the second floor was Käthe studio. It was a completely plain room as she liked to work without any visual distractions. Käthe drew numerous studies of hands; a young nude woman (probably Jeep); and some self-portraits. (26)

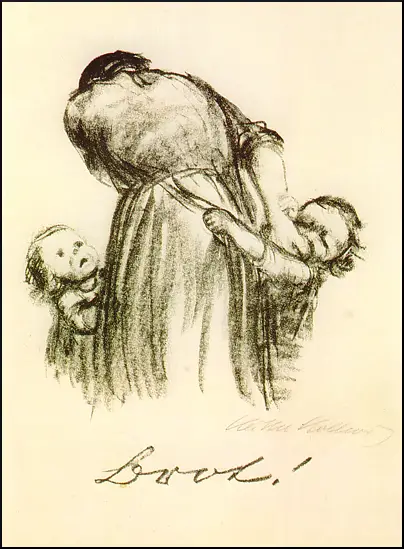

In May, 1892, Käthe Kollwitz gave birth to her first child, a son, they called Hans. She soon began to use her son as a model. In his first few months she did eighteen drawings of him. Karl kept his promise and "did everything possible so that I would have time to work". She recalled that this "quiet, hardworking life" was "unquestionably good for my further development". As soon as they could afford it, a live-in housekeeper was hired to help her with her child-rearing duties. (27)

In 1893 Käthe took part in a joint exhibition of Berlin artists. One leading art critic, Ludwig Pietsch, complained that the organisers had allowed a woman to exhibit. However, another critic, Julius Elias, wrote: "In almost every respect the talent of a young woman stands out. A young woman who will be able to bear the insult of this first rejection lightly, for she is assured of a rich artistic future. Frau Kollwitz perceives nature readily and intensely, using clear, well-formed lines. She is attracted to unusual light and deep colour tones. Hers is a very earnest display of artwork." Encouraged by these positive comments, Kollwitz began work on a series of drawings that illustrated the novel, Germinal.(28)

Käthe Kollwitz - The Revolt of the Weavers

On 28th February, 1893, Käthe Kollwitz attended a performance of The Weavers, a new play by Gerhart Hauptmann. The play dealt with a real historical event. In June 1844 disturbances and riots occurred in the Prussian province of Silesia during an economic recession. A large number of weavers attacked warehouses and destroyed the new machinery that was being used in the industry. The Prussian Army arrived on the scene and in an attempt to restore order fired into the crowd, killing 11 people and wounding many others. The leaders of the weavers were arrested, flogged, and imprisoned. Karl Marx wrote about this event, claiming that the uprising marked the birth of a German workers' movement.

The theatre critic, Barrett H. Clark, has argued in The Continental Drama of Today (1914): "Hauptmann may be said to have created a new form of drama in The Weavers, and that form is what may be designated as the tableau series form, with no hero but a community. As the play is not a close-knit entity, the first act is casual, and might open at almost any point; and since it starts with a picture, or part of a picture, there is hardly anything to be known of the past. The result is that no exposition is needed. The audience sees a state of affairs, it does not lend its attention and interest to a story or the beginning of a plot or intrigue. This first act merely establishes the relation between the weavers and the manufacturers. There is no direct hint given in the first act as to what is to come in the second; the first is a play in itself, a situation which does not necessarily have to be developed. It does, however, prepare for the revolt, by showing the discontent among the downtrodden people, and it also enlists the sympathy of the audience." (29)

Despite a Berlin police ban on all public performances of this play, the Berliner Freie Bühne, featuring Else Lehmann, performed the work. Käthe Kollwitz later recalled: "The performance was given in the morning.... My husband's work kept him from going, but I was there, burning with anticipation. The best actors of the day participated, with Else Lehmann playing the young weaver's wife. In the evening there was a large gathering to celebrate, and Hauptmann was hailed as the leader of youth.... The performance was a milestone in my work. I dropped the series on Germinal and set to work on The Weavers." (30)

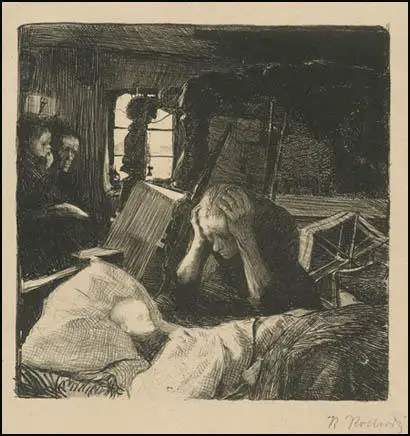

Kollwitz spent the next five years producing a series of lithographs illustrating the uprising. 1. Poverty; 2. Death (a weaver's child dies of hunger); 3. Conspiracy (the weavers plan to avenge the deaths of their children); 4. Weavers on the March (the weavers march to the factory owner's home); 5. Attack (the weavers attack the mansion owned by the factory owner); 6. The End (the consequences of the uprising). It has argued: "Kollwitz's meticulous craft and her aesthetic and political vision of the working-class man and woman are apparent in The Revolt of the Weavers. The first lithograph, Poverty, pictures a crowded room in which a child is sleeping in a bed in the foreground. The mother, with deeply wrinkled brow, is stooped over the bed, her large, bony hands clutching her head in despair. Father and another child sit huddled by the back window, anxiously watching the sleeping child. The small window lightens the sleeping child's face, but only partially draws out the features of the watching family. The parents' steady gaze at their sick child reflects uneasy despair. An empty loom, ominous sign of unemployment, fills the back of the room." (31)

In 1896 Käthe Kollwitz gave birth to her second son, Peter. The arrival of another baby added to her burdens but also stimulated her creativity. She later explained that this "wretchedly limited" her "working time". However, her work did not suffer: "I was more productive because I was more sensual, I lived as a human being must live, passionately interested in everything." (32)

In the summer of 1896 Karl Schmidt became very ill. With his wife he moved to Rauschen to recuperate. Käthe Kollwitz produced a drawing for him on his seventieth birthday. Käthe recorded in her diary: "He was overjoyed. I can still remember how he ran through the house calling again and again to Mother to see what little Käthe had done." Kollwitz's father died in the spring of 1897. Käthe admitted that his death affected her art: "I was so depressed because I could no longer give him the pleasure of seeing the work publicly exhibited that I dropped the idea of a show." However, her friend, Anna Plehn, took over and entered The Revolt of the Weavers in the Great Berlin Exhibition. Death sold on the third day of the exhibition for 500 marks. (33)

Adolf Menzel, who was considered the most important artist in the country, was so impressed with The Revolt of the Weavers that he proposed, as a member of the jury, to award the prestigious Gold Medal to Kollwitz. However, Wilhelm II, who disapproved of her socialist sympathies, vetoed the nomination. The following year, it was was exhibited at the Dresden Museum. The museum director proposed to the King of Saxony that Kollwitz be awarded the gold medal. The monarch agreed and in 1899 he conferred upon her the award. (34) She wrote in her journal: "from then on... I was counted among the foremost artists of the country". (35)

Käthe Kollwitz - Art and Socialism

Käthe Kollwitz now began work on another series of etchings that dealt with the harsh conditions being endured by the working-class in Berlin. Completed in 1900, The Downtrodden, examines the lives of three victims of poverty. Kollwitz later recalled: "My real motive for choosing my subjects almost exclusively from the life of the workers was that only such subjects gave me a simple and unqualified way what I felt to be beautiful... The broad freedom of movement in the gestures of the common people had beauty. Middle-class people held no appeal for me at all. Bourgeois life as a whole seemed to me pedantic. The proletariat, on the other hand, had a grandness of manner, a breadth to their lives." (36)

Kollwitz was motivated by capturing the life of working-class people, "in their native rugged simplicity". She was not interested in those who concerned themselves with clothes, cosmetics, class, education, or convention. Kollwitz told Agnes Smedley: "I have never been able to see beauty in the uppere-class, educated person; he's superficial; he's not natural or true; he's not honest, and he's not a human being in every sense of the word." (37)

Kollwitz was especially interested in the lives of women. She often drew the women in her husband's waiting room: "The working-class woman shows me, through her appearance and being, much more than the ladies who are totally limited by conventional behaviour. The working-class woman shows me her hands, her feet and her hair. She lets me see the shape and form of her body through her clothes. She presents herself and the expression of her feelings openly, without disguises." (38)

Kollwitz agreed to teach part-time at the Berlin School for Women Artists. This included graphic arts and life drawing. However, she never felt comfortable doing this work as she was shy among strangers and accustomed to working in the unbroken solitude of a small, single room: "I had to show the class how to make an etching ground. The process was a book with seven seals to me and I perspired with embarrassment as I started to trot out my meager knowledge before the eager girls standing in a group around me." (39)

In 1904 Kollwitz visited Paris where she met Lily and Heinrich Braun, who were proposing a new socialist art journal, The New Society. While in the city she visited three of her fellow students at the Munich Women's Art School who had settled in France. One of the women was living in extreme poverty with her eleven-year-old son. Kollwitz agreed for Georg Gretor, to live with her in Berlin. (40)

Kollwitz also visited the studio of Auguste Rodin. She later recalled: "I shall never forget that visit. Rodin himself was taken up with other visitors. But he told us to go ahead and look at everything we could find in his atelier. In the center of a group of his big sculptures the tremendous Balzac was enthroned. He had small plaster sketches in glass cases. It was possible to see the full scope of his work, as well as to feel the personality of the old master." (41)

Max Klinger used his success to help younger artists. This included establishing the Villa Romana Prize. He purchased a villa in Florence, to which he invited outstandingly gifted artists (and their families) to live for cost free for up to a year. According to Martha Kearns the idea was for the artist to be given the opportunity to absorb "the rich influences of Medieval and Renaissance works of Florentine art." In 1906 Kollwitz was awarded the prize. She took her son Peter to the villa to help him recover from tuberculosis. (42)

Kollwitz spent her time studying the frescoes, sculpture, architecture and painting in the city. In her journal she explained that she found little to inspire her and during her stay in Italy she produced no work: "The enormous galleries are confusing, and they put you off because of the masses of inferior stuff in the pompous Italian vein. And so I have been trying the churches, with better luck. There are magnificent frescoes in the churches... And finally I again ventured into the Pitti and Uffizi Galleries. There are beautiful works here and there in them, but only here and there, it seems to me." (43)

While in Florence Kollwitz met her old friend, Emma Jeep, who had recently married Arthur Bonus. She also spent time with local artist, Constanza Harding. After Peter Kollwitz had returned to Berlin, the two women decided to hike through the tiny villages along the coastal route to Rome. A journey of around 150 miles. During the holiday the two women became very close again and on her arrival on 13th June, 1907, she described it as one of her life's great adventures. (44)

On her return to Germany she completed the series of drawings, The Peasant War. To produce the seven scenes she "combined aquatint and soft ground with the regular etching process". It is claimed by critics that Raped is one of the earliest pictures in Western art to depict a female victim of sexual violence sympathetically and from a woman's point of view. When the series was issued in 1908 it confirmed Kollwitz's stature as the most important graphic artists working in Europe. (45)

Simplicissimus

In 1909 Simplicissimus, a progressive journal published in Munich and run by a co-operative of artists that included Ludwig Thoma, Thomas Heine, Olaf Gulbransson, Rudolf Wilke and Edward Thony, commissioned her to produce a series of five drawings entitled Portraits of Misery. This was as a response to criticisms from the leaders of the Social Democratic Party (SDP). One newspaper reported: "The German worker simply does not look the way Simplicissimus portrays him. The worker, who strives courageously for the recognition of his personal worth, is insulted when he is portrayed as a drunkard or as a ragged street urchin living in an evil-smelling hovel." (46)

Käthe Kollwitz based her charcoal drawings on the working-class people who visited her husband's surgery for treatment. "I met the women who came to my husband for help and so, incidentally, came to me, I was gripped by the full force of the proletarian's fate. Unsolved problems such as prostitution and unemployment grieved and tormented me, and contributed to my feeling that I must keep on with my studies of the lower classes. And portraying them again and again opened a safety-valve for me; it made life bearable." When they were finished she wrote in her journal: "A happy day yesterday. Finished drawing the fifth and last plate for Simplicissimus... I am so glad that I can work well and easily now... As a result of so much working on studies I have at last reached the point where I have a certain background of technique which enables me to express what I want without a model." (47)

Hans Kollwitz pointed out that his mother found it difficult to express her emotions to her children: "Along with this reserve in talking about or showing love went a sisinclination to speak about feelings at all, or about any personal matters. She could speak about other people and what happened to them, about books, about problems, even about her own works; but actually she never spoke about herself. This was consistent with the attitude which had prevailed in her grandparents' and parents' households: that one's work could be considered important, but oneself never... To outsiders my mother gave the impression of being impregnable; only in her diaries can you see how she struggled with the antagonist within herself, and how essential that struggle was to her development." (48)

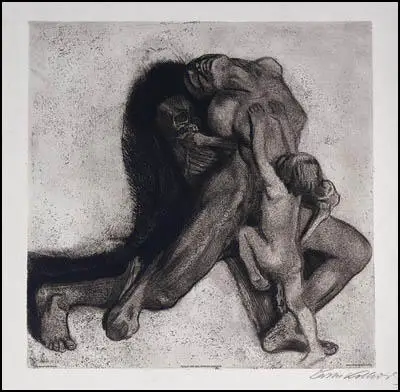

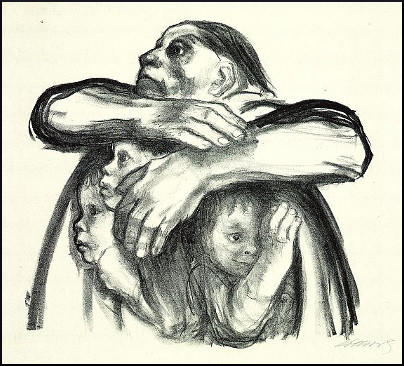

In 1910 Kollwitz completed Death, Woman, and Child. The author of Käthe Kollwitz (1976) has argued that Kollwitz identified with the mother figure in the picture: "The soft-ground etching is a masterpiece of line, space, and content. In its illustration of psychological tension through the drama of the body, Death and the Woman equals the artistry and emotional depth of Michelangelo's Rebellious Slave. A nude woman resembling the artist strains between a child who reaches for her and the skeleton of Death, which grasps her, pinning back her arms. The child touches her breasts, but cannot reach her tormented face; neither is the mother able to wrench free of Death to touch her child. The woman is bound, crucifix like, between Death and child, but in a dynamic pose: the line of her body curves powerfully from the right foot, through her taut thigh, to the near-circular arc of her breasts and her straining head, wrenched back in agony." (49)

Kollwitz, now aged 43, wrote in her journal that she now spent most of her time in her studio working on her art: "I am gradually approaching the period in my life when work comes first. When both the boys went away for Easter, I hardly did anything but work. Worked, slept, ate and went for short walks. But above all I worked... No longer diverted by other emotions, I work the way a cow grazes." (50)

During this period she produced a poster on the housing crisis in Berlin. Underneath the drawing of a young woman holding a baby in her arms, were the words: "600,000 Berliners live in apartments in which five or more persons are living. Some hundred thousand children live in tenement housing without playgrounds." Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had already described Kollwitz's work as the "art of the gutter" ordered the posters to be removed on the grounds that it incited class hatred. (51)

First World War

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28th June, 1914, triggered off the First World War. Käthe's two sons, Hans and Peter, immediately joined the German Army. She wrote in her journal: "Nothing is real but the frightfulness of this state, which we almost grow used to. In such times it seems so stupid that the boys must go to war. The whole thing is so ghastly and insane. Occasionally there comes that foolish thought: how can they possibly take part in such madness? And at once the cold shower: they must, must!" (52)

On 23rd October, 1914, Peter Kollwitz was killed at Dixmuide in Belgium on the Western Front. She wrote in her journal: "My Peter, I intend to try to be faithful.... What does that mean? To love my country in my own way as you loved it in your way. And to make this love work. To look at the young people and be faithful to them. Besides that I shall do my work, the same work, my child, which you were denied. I want to honor God in my work, too, which means I want to be honest, true, and sincere.... When I try to be like that, dear Peter, I ask you then to be around me, help me, show yourself to me. I know you are there, but I see you only vaguely, as if you were shrouded in mist. Stay with me.... my love is different from the one which cries and worries and yearns.... But I pray that I can feel you so close to me that I will be able to make your spirit." (53)

Kollwitz found it difficult to use her art to deal with her grief. She wrote in her journal: "Stagnation in my work... When it comes back (the grief) I feel it stripping me physically of all the strength I need for work. Make a drawing: the mother letting her dead son slide into her arms. I might make a hundred such drawings and yet I do not get any closer to him. I am seeking him. As if I had to find him in the work... For work, one must be hard and thrust outside one-self what one has lived through. As soon as I begin to do that, I again feel myself a mother who will not give up her sorrow. Sometimes it all becomes so terribly difficult." (54)

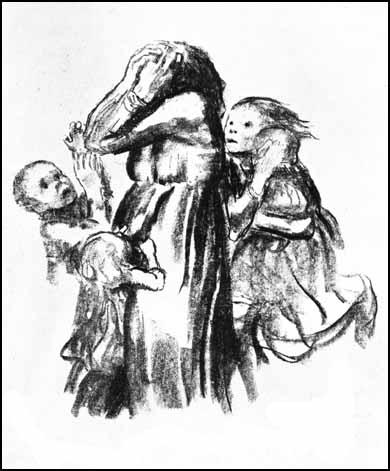

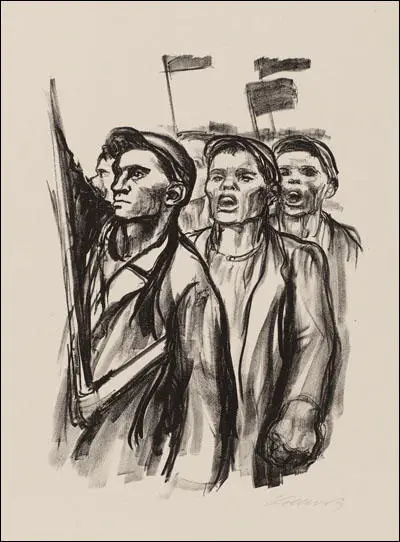

In 1916 she drew Anguish: The Widow. According to Martha Kearns: "A pregnant working-class woman, gaunt and harried, stands nearly full-length before us; her large-knuckled hands, cupped to hold and embrace, reach out limply in empty space. The woman is shocked and despondent from mourning; the woman is Kollwitz, who felt the widow's grief through the loss of her own son; the poor woman's desolation is her own." (55)

On 13th June, 1916, Käthe had been married to Karl Kollwitz for twenty-five years. In her journal she wrote: "I have never been without your love, and because of it we are now so firmly linked after twenty-five years. Karl, my dear, thank you. I have so rarely told you in words what you have been and are to me. Today I want to do so, this once. I thank you for all you have given me out of your love and kindness. The tree of our marriage has grown slowly, somewhat crookedly, often with difficulty. But it has not perished. The slender seedling has become a tree after all, and it is healthy at the core. It bore two lovely, supremely beautiful fruits." (56)

To commemorate Käthe's fiftieth birthday she was given a retrospective exhibition in Berlin. In May 1917 her sister, Lise Schmidt, wrote about the show in the socialist monthly, Sozialistische Monatshefte. Käthe wrote about the article in her journal: "She (Lise) makes a point which is for the most part ignored when people assert that my one subject is always the lot of the unfortunate. Sorrow isn't confined to social misery. All my work hides within it life itself, and it is with life that I contend through my work. At any rate I felt that Lise's conception is very close to mine." (57)

Käthe Kollwitz wanted to produce more positive art but found this impossible to do during the First World War. "How can one cherish joy when there is really nothing that gives joy? And yet the imperative is surely right. For joy is really equivalent to strength. It is possible to have joy within oneself and yet shoulder all the suffering. Or is it really impossible? If all the people who have been hurt by the war were to exclude joy from their lives, it would almost be as if they had died. Men without joy seem like corpses." (58)

Kollwitz also wrote about her feelings towards the war. She admitted that in 1914 she had not argued against her sons joining the German Army "because there was the conviction that Germany was in the right and had the duty to defend herself." However, by 1917 she had changed her view of the war: "The feeling that we were betrayed then, at the beginning. And perhaps Peter would still be living had it not been for this terrible betrayal. Peter and millions, many millions of other boys, all betrayed." (59)

Käthe Kollwitz and the German Revolution

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Several leading socialists arrived in the city to support the new regime. This included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution. (60)

Kollwitz supported the revolutionaries but was opposed to the use of violence. Workers, soldiers and sailors responded to the news by going on strike and mutinying throughout Germany. Workers' Councils took control of factories and Soldiers' Councils undermined the authority of military officers. Käthe Kollwitz joined in this rebellion by helping the forming of a Workers' and Artist Council in Berlin. She also produced a charcoal drawing entitled, Revolution 1918 (1918). One critic pointed out the "charcoal drawing, transmits the passion, choas, and joy of the working classes as they scream, wave, and reach out to each other in the heat of revolution." (61)

The Social Democratic Party temporary government was less enthusiastic about the demands of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils that included the socialization of key industries, the redistribution of land and a purge of the army, to be replaced by a people's militia. Instead the SPD government announced national elections. As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League." (62)

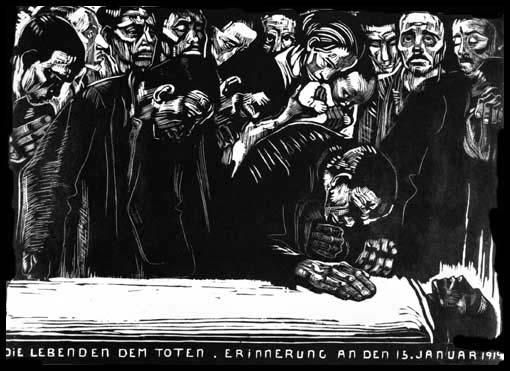

Luxemburg was aware that the Spartacus League only had 3,000 members and not in a position to start a successful revolution. The Spartacus League consisted chiefly of innumerable small and autonomous groups scattered all over the country. John Peter Nettl has argued that "organisationally Spartakus was slow to develop... In the most important cities it evolved an organised centre only in the course of December... and attempts to arrange caucus meetings of Spartakist sympathisers within the Berlin Workers' and Soldiers' Council did not produce satisfactory results." (63)

Pierre Broué suggests that the large meetings helped to convince Karl Liebknecht that a successful revolution was possible. "Liebknecht, an untiring agitator, spoke everywhere where revolutionary ideas could find an echo... These demonstrations, which the Spartakists had neither the force nor the desire to control, were often the occasion for violent, useless or even harmful incidents caused by the doubtful elements who became involved in them... Liebknecht could have the impression that he was master of the streets because of the crowds which acclaimed him, while without an authenic organisation he was not even the master of his own troops." (64)

On 1st January, 1919, there was a convention of the Spartacus League. Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Levi and Leo Jogiches all recognised that a "successful revolution depended on more than temporary support for certain slogans by a disorganised mass of workers and soldiers". (65) They were outvoted on this issue. As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "In vain did she (Luxemburg) try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising." (66)

On the 5th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. Groener later testified that his aim in reaching accommodation with Ebert was to "win a share of power in the new state for the army and the officer corps... to preserve the best and strongest elements of old Prussia". Ebert was motivated by his fear of the Spartacus League and was willing to use "the armed power of the far-right to impose the government's will upon recalcitrant workers, irrespective of the long-term effects of such a policy on the stability of parliamentary democracy". (67)

The soldiers who entered Berlin were armed with machine-guns and armoured cars and demonstrators were killed in their hundreds. Artillery was used to blow the front off the police headquarters before Eichhorn's men abandoned resistance. "Little quarter was given to its defenders, who were shot down where they were found. Only a few managed to escape across the roofs." (68)

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal." (69)

On the morning of the funeral Käthe Kollwitz visited the Liebknecht home to offer sympathy to the family. At their request, she made drawings of him in his coffin. She noted that there were red flowers around his forehead, where he had been shot. She wrote in her journal: "I am trying the Liebknecht drawing as a lithograph... Lithography now seems to be the only technique I can still manage. It's hardly a technique at all, its so simple. In it only the essentials count." However, she changed her mind and it became a woodcut. (70)

The Karl Liebknecht woodcut was attacked by the German Communist Party (KPD) because it had not been produced by a member of the party. Kollwitz wrote in her journal: "As an artist who moreover is a woman cannot be expected to unravel these crazily complicated relationships. As an artist I have the right to extract the emotional content out of everything, to let things work upon me and then give them outward form. And so I also have the right to portray the working class's farewell to Liebknecht, and even dedicate it to the workers, without following Liebknecht politically." (71)

In 1919 Kollwitz became the first woman to be elected to full professorship at the Prussian Academy of Arts. (72) As part of the position she was given a large, fully equipped studio with side rooms. In her new studio she began work on a series of lithographs that dealt with the impact of the First World War on women. Kollwitz later recorded: "I first began the war series as etchings. Came to nothing... I can no longer etch; I'm through with that for good. and in lithography there are the inadequacies of the transfer paper. Nowadays lithographic stones can only be got to the studio by begging and pleading, and cost a lot of money, and even on stones I don't manage to make it come out right. Why can't I do it any more? The prerequisites for artistic works have been there - for example in the war series. First of all the strong feeling - these things come from the heart - and secondly they rest on the basis of my previous works, that is, upon a fairly good foundation of technique." (73)

Kollwitz's failure to support the Spartacus League Uprising made her realise that she was not as revolutionary as she thought: "I have been through a revolution, and I am convinced that I am no revolutionist. My childhood dream of dying on the barricades will hardly be fulfilled, because I should hardly mount a barricade now that I know what they are like in reality. And so I know now what an illusion I lived in for so many years. I thought I was a revolutionary and was only an evolutionary. Yes, sometimes I do not know whether I am a socialist at all, whether I am not rather a democrat instead." (74)

In 1920 she produced a self-portrait, Woman Lost in Thought. It reflected her mood at the time. She wrote: "I am disillusioned with all the hate that is in the world. I long for Socialism which allows people to live - the world has seen enough murder, lies, and corruption." This was followed with Death with Women in Lap, in which a tired woman is cradled in the lap and arms of Death. She wrote in her journal: "I am no longer expanding outward; I am contracting into myself. I mean that I am noticeably growing old." (75)

Peace Activist

Later that year Kollwitz joined Albert Einstein, George Grosz, Maxim Gorki, George Bernard Shaw, Henri Barbusse, Willi Münzenberg, Clara Zetkin, Upton Sinclair and Ernst Toller to form the International Workers Aid (IAH). She produced several posters for the organisation including Help Russia and Vienna is Dying! Save her Children!. (76) During this period she wrote: "At such moments, when I know I am working with an international society opposed to war, I am filled with a warm sense of contentment. I know, of course, that I do not schieve pure art... But it is still art." (77)

Käthe Kollwitz finished her series on the First World War in 1923. She told her friend, Erna Kruger: "Everything has gone so well with me concerning my work... If there is a section I have not re-worked, I do not know about it. A work of many years is finally coming to a close. They include an analysis of the piece of life that the years of life 1914-1918 encompass. These four years were very difficult to grasp... I have received a commission from the International Trade Union Congress to make a poster against war. That is a task that makes me happy. Some may say a thousand times, that this is not pure art, which has a purpose. But as long as I can work, I want to be effective with my art." (78)

Kollwitz was also an active member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). The organisation was established in 1915 and after the war campaigned for peace, disarmament and international co-operation. Other members included Jane Addams, Mary Sheepshanks, Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Sophonisba Breckinridge, Aletta Jacobs, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan and Rosika Schwimmer.

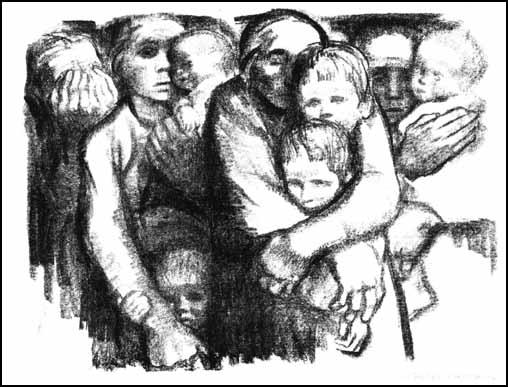

Kollwitz produced lithographs of war-stricken mothers and children for the organisation. that were distributed as postcards. She also produced a poster, The Survivors, which showed those uprooted by war, for the International Trade Congress (ITC). (79) She had wanted to draw a feminist-orientated picture of "mothers pressed together like animals, protecting their brood in a cluster of black", but the ITC preferred a depiction of survivors. The final drawing showed those uprooted by the war - "the parents, widows, blind people, and all their children with their fearful, questioning, helpless eyes and pale faces." (80)

In 1924 she produced another anti-war poster, Never Again War. The author of Käthe Kollwitz (1976) has pointed out: "In this work her anger over the war dominates her sorrow. A zealous youth summons others to pacifism: his black eyebrows arch, his hair sweeps back dramatically as he stretches his right arm, first two fingers pointing in a visual exclamation point to the clarion call Never Again War!, writ large on either side of his arm." (81)

In September 1925 Kollwitz was interviewed by the journalist, Agnes Smedley, who argued: "She (Kollwitz) is now fifty-eight years of age, and remains unimpressed by attentions, medals, books, or professorships. Her ceaseless physical activity would lead one to believe she is no more than forty. Her life is as simple as that of an ordinary working woman, and she still lives in the workers' section of North Berlin. Her gaze is direct and her voice startlingly strong, and she sees far beyond those who bring her superficial, external tributes or who try to use her for their own propaganda purposes. She is a silent person, but when she speaks it is with great directness, without trimmings to suit the prejudices of her hearers. Many people, before meeting her, expect to see a bitter woman. But they see, instead, a kind - very kind - woman to whom love - strong, love, however - is the rule of life." (82)

In 1925 Käthe Kollwitz completed a series of woodcuts entitled The Proletariat. As with her other work, the woodcuts are made from the point of view of a working-class woman having to deal with living in poverty. The most disturbing image in the series is Hunger "shows terrified women and children crawling through thick darkness, as Death, represented as a skull, brandishes a lasso over their heads. The Children Die, the final frame, is the sharpest and most emphatic of the series. Stupefield with grief, a mother holds a child's coffin in her work-muscled hands. Thin, long-knived strokes abstract her features, giving her face the impressionable quality of rock." (83)

On the death of Peter Kollwitz during the First World War, Käthe attempted to create a memorial to her son. Every attempt she made ended in failure. Eventually she decided to make two sculptures, The Mother and The Father. She was given permission to place them in the cemetery where he was buried. In June, 1926, Käthe and Karl Kollwitz visited the cemetery in Dixmuide in Belgium, to decide where they were to be placed. She later recalled: "The cemetery is close to the highway.... The entrance is nothing but an opening in the hedge that surrounds the entire field. It was blocked by barbed wire which a friendly young man bent aside for us; then he left us alone. What an impression: cross upon cross.... on most of the graves there were low, yellow wooden crosses. A small metal plaque in the center gives the name and number. So we found our grave.... We cut three tiny roses from a flowering wild briar and placed them on the ground beside the cross. All that is left of him lies there in a row-grave. None of the mounds are separated; there are only the same little crosses placed quite close together.... and almost everywhere is the naked, yellow soil.... at least half the graves bear the inscription unknown German... We considered where my figures might be placed... What we both thought best was to have the figures just across from the entrance, along the hedge.... Then the kneeling figures would have the whole cemetery before them." (84)

In 1927 Kollwitz was invited to visit the Soviet Union. Although she was a supporter of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and opposed communist revolution, she did accept that the country had introduced some important progressive reforms. Kollwitz wrote in Arbeiters International Zeitung: "This is not the place for us to discuss why I am not a Communist. But it is the place for me to state that, as far as I am concerned, what has happened in Russia during the last ten years seems to be an event which both in stature and significance is comparable only with that of the great French Revolution. An old world, sapped by four years of war and undermined by the work of revolutionaries, fell to pieces in November 1917. The broad outline of a new world was hammered together. In an essay written during the early days of the Soviet Republic, Maksim Gorki speaks of flying with one's soles turned upwards. I believe that I too can sense such flying in the gale inside Russia. For this flying of theirs, for the fervour of their beliefs, I have often envied the Communists." (85)

The memorial to her son was not finished until 1931. It went on display at the Prussian Academy of Arts until being moved to Belgium: "For years I worked on them in utter silence, showed them to no one, scarcely even to Karl and Hans; and now I am opening the doors wide so that as many people as possible may see them. A big step which troubles and excites me; but it has also made me very happy because of the unanimous acclaim of my fellow artists." Otto Nagel described the memorial as the "artistic sensation of the day". (86)

Nazi Germany

In the General Election that took place in September 1930, the Nazi Party increased its number of representatives in parliament from 14 to 107. Adolf Hitler was now the leader of the second largest party in Germany. The Social Democratic Party was the largest party in the Reichstag, but it did not have a majority over all the other parties, and the SPD leader, Hermann Muller, had to rely on the support of others to rule Germany. Harold Harmsworth, 1st Lord Rothermere, wrote in The Daily Mail after the general election result: "What are the sources of strength of a party which at the general election two years ago could win only 12 seats, but now, with 107, has become the second strongest in the Reichstag, and whose national poll has increased in the same time from 809,000 to 6,400,000? Striking as these figures are, they stand for something far greater than political success. They represent the rebirth of Germany as a nation." (87)

Kollwitz watched these political developments with deep misgivings. The Nazi's use of brute force to suppress a workers' rally angered her; it also alerted her to the imminent political danger. She reacted against the political repression by drawing Demonstration, a scene of a workers' rally in which a group of staunch men, singing, protest civil and economic policies. (88)

In May 1932 General Hans von Seeckt joined up with Alfred Hugenberg, Hjalmar Schacht, and several industrialists, to call for the uniting of the parties of the right. They demanding the resignation of Heinrich Brüning. Germany's president, Paul von Hindenburg, agreed and forced him to leave office and on 1st June he was replaced as chancellor by Franz von Papen. The new chancellor was also a member of the Catholic Centre Party and, being more sympathetic to the Nazis, he removed the ban on the SA. The next few weeks saw open warfare on the streets between the Nazis and the Communists during which 86 people were killed. (89)

On 4th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler had a meeting with Franz von Papen and decided to work together for a government. It was decided that Hitler would be Chancellor and Von Papen's associates would hold important ministries. "They also agreed to eliminate Social Democrats, Communists, and Jews from political life. Hitler promised to renounce the socialist part of the program, while Von Papen pledged that he would obtain further subsidies from the industrialists for Hitler's use... On 30th January, 1933, with great reluctance, Von Hindenburg named Hitler as Chancellor." (90)

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag parliamentary building caught fire. It was reported at ten o'clock when a Berlin resident telephoned the police and said: "The dome of the Reichstag building is burning in brilliant flames." The Berlin Fire Department arrived minutes later and although the main structure was fireproof, the wood-paneled halls and rooms were already burning. (91)

Hermann Göring, who had been at work in the nearby Prussian Ministry of the Interior, was quickly on the scene. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels arrived soon after. So also did Rudolf Diels: "Shortly after my arrival in the burning Reichstag, the National Socialist elite had arrived. On a balcony jutting out of the chamber, Hitler and his trusty followers were assembled." Göring told him: "This is the beginning of the Communist Revolt, they will start their attack now! Not a moment must be lost. There will be no mercy now. Anyone who stands in our way will be cut down. The German people will not tolerate leniency. Every communist official will be shot where he is found. Everybody in league with the Communists must be arrested. There will also no longer be leniency for social democrats." (92)

Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD) should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". Orders were given for all KPD members of the Reichstag to be arrested. This included Ernst Torgler, the chairman of the KPD. Göring commented that "the record of Communist crimes was already so long and their offence so atrocious that I was in any case resolved to use all the powers at my disposal in order ruthlessly to wipe out this plague". (93)

Käthe Kollwitz helped organise a public manifesto calling for unity between the Social Democrat Party and the German Communist Party in order to combat to rise of fascism. Hitler responded by demanding that Kollwitz and Heinrich Mann, another organiser of the manifesto, should resign from the Prussian Academy of Arts. Kollwitz wrote to her friend, Emma Jeep: "Has the Academy affair reached your ears yet? That Heinrich Mann and I, because we signed the manifesto calling for unity of the parties of the left, must leave the Academy. It was all terribly unpleasant for the Academy directors. For fourteen years... I have worked together peacefully with these people. Now the Academy directors have had to ask me to resign. Otherwise the Nazis had threatened to break up the Academy. Naturally I complied. So did Heinrich Mann. Municipal Architect Wagner also resigned, in sympathy." (94)

After losing her Academy studio, Kollwitz was unable to continue with her sculpture. Now aged 67, she decided to do a series of lithographs on her own impending death: "I thought that now that I am really old I might be able to handle this theme in a way that would plumb depths... But that is not the case... At the very point when death becomes visible behind everything, it disrupts the imaginative process... I start off indecisively, soon tire, need frequent pauses and must turn for counsel to my own earlier works." (95)

Käthe Kollwitz continued to criticise Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Government. Along with her friend, Otto Nagel, she gave an interview with Izvestia. In July, 1936, she was arrested by the Gestapo. They wanted to know the names of other German artists who shared her anti-Nazi beliefs. They warned her that if she did not cooperate she would be sent to a concentration camp. She remained silent and because of her age, she was released. (96)

On 27th November, 1936, Joseph Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." It is estimated that 31 of Kollwitz's works were confiscated. (97)

In 1938 she finished the sculpture, Tower of Mothers. When this was shown at a local exhibition, it was seized by the Nazi government and described as being an example of "degenerate art". She wrote in her journal: "There is this curious silence surrounding the expulsion of my work from the Academy show.... Scarcely anyone had anything to say to me about it. I thought people would come, or at least write - but no. Such a silence around us." (98)

Second World War

The Nazi government also banned Karl Kollwitz from working as a doctor in Berlin. Eric Cohn, a wealthy art collector in the United States, purchased some of her sculptures that enabled the couple to buy enough food to survive. Cohen also offered to help Kollwitz to take refuge in the United States, but she refused as she did not want to be separated from her family. Karl, who had an unsuccessful eye operation for cataracts, became increasing weak and by the outbreak of the Second World War he was completely bedridden. Käthe, who had to use a cane for walking, became his constant nurse and companion. He died on 19th July, 1940. (99)

In January, 1942, Kollwitz, aged 74, produced her last lithographic, Seed Crops should not be Milled. She wrote in her journal, "I have finished my lithograph... This time the seed for the planting - sixteen-year-old boys - are all around the mother, looking out from under her coat and wanting to break loose. But the old mother who is holding them together says, No! You stay here! For the time being you may play rough-and-tumble with one another. But when you are grown up you must get ready for life, not for war again." (100)

Käthe Kollwitz, whose grandson, Peter, was named after her son killed in the First World War, joined the German Army. He was killed during the advance on Stalingrad in October, 1942. His father, Hans Kollwitz, recalled: "Even then she bore herself proudly, did not grieve openly, scarcely wept; she tried to give us strength to bear it. But the blow had been deep and damaging." (101)

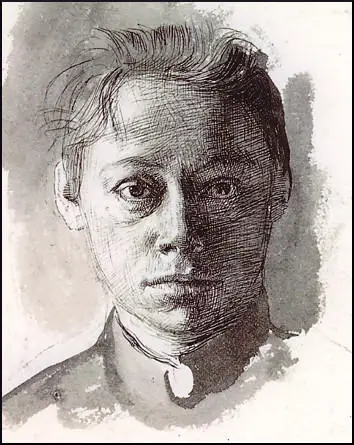

In 1943 Kollwitz produced her last self-portrait. Her biographer, Martha Kearns, has argued: "It is the last of eighty-four self-portraits, possibly the longest chronology of self-portraits by a woman in Western art, certainly a stunning psychological charting of a woman's life." (102)

The terror-bombing of Berlin meant that in the summer of 1943, Kollwitz was forced to seek refuge in the home of a friend in Nordhausen. She was a prolific letter writer and in one letter to Georg Gretor, her adopted son, she wrote: "Oh, Georg, how good it all was... the fullness and richness of our lives overwhelms me again and again with feelings of gratitude. Let us tell you once more how we all have loved you." (103)

On 23rd November, 1943, her apartment on 25 Weissenburger Strasse was destroyed by bombs and she lost family photographs, letters and mementos of her husband, sons and grandsons. She wrote: "It was my home for more than fifty years. Five persons whom I have loved so dearly have gone away from those rooms forever. Memories filled all the rooms... Only an idea remains, and that is fixed in the heart." (104)

A week later her son's home was also destroyed during a bombing raid. Kollwitz wrote in her journal: "every war already carries within it the war which will answer it. Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed... That is why I am so wholeheartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in a world socialism... Pacifism simply is not a matter of calm looking on; it is work, hard work." (105)

Käthe Kollwitz died, aged seventy-eight, at Moritzburg on 22nd April, 1945. Her biographer, Martha Kearns, commented: "She died without worldly possessions, but rich in her own person." In her time she had developed the strength "to take life as it is... to do one's work powerfully... not to deny oneself, the personality one happens to be, but to embody it." (106)

Primary Sources

(1) Martha Kearns, Käthe Kollwitz (1976)

Käthe's first university professor, Swiss-born Karl Stauffer-Bern, was a jack-of-all-arts; at twenty-seven, he had already displayed talents as a poet, painter, sculptor, and etcher, and was a perceptive teacher as well. Stauffer-Bern had little respect for the sort of work favored by the Academy in 1885 - enormous, academic canvases of battlefields. He apparently had not much more respect for his own work, which had brought him great success; he pronounced his admirers "blind." During this time he wrote to a friend that "among Berlin's one-and-a-half-million inhabitants, there isn't anyone of my own age who I feel is a kindred spirit in the world of art, so here I am, with no one to turn to for companionship, it's the very devil."

Käthe herself fared better in finding companionship. At her first meeting with a sister student, Beate (or Emma) Jeep, the two became fast friends.... Eagerly Jeep and Schmidt shared their portfolios with one another. Then Käthe presented hers - consisting largely of anecdotes, and illustrations to poems - to Stauffer-Bern. At first he thought her work typical of her locale, for the subjects were Slavic and Russian peasants drawn in a realistic style. But when he saw The Emigrants, he exclaimed, "But this is just like a Klinger!"

She had never heard of Max Klinger, Prussia's most skilled artist of the then popular naturalism, a school of thought which deemed people to be predetermined victims in a bitter struggle for survival. As an art form, naturalism emphasized photo like images of actual persons, scenes, and conditions, often in the most minute, even microscopic detail. Unlike artists working in other styles, naturalist artists featured women as subjects as frequently as men. The Emigrants convinced Stauffer-Bern that Käthe could excel in the graphic arts of etching and lithography, requiring expert, subtle drawing skill, in which Klinger had perfected his naturalist techniques. Although Käthe objected when he urged her to follow in Klinger's path, "Stauffer-Bern's instruction was extremely valuable for my development. I wanted to paint, but he kept telling me to stick to drawing."

(2) Käthe Kollwitz, diary entry (30th September, 1914)

Nothing is real but the frightfulness of this state, which we almost grow used to. In such times it seems so stupid that the boys must go to war. The whole thing is so ghastly and insane. Occasionally there comes that foolish thought: how can they possibly take part in such madness? And at once the cold shower: they must, must!

(3) Käthe Kollwitz, diary entry (30th December, 1914)

My Peter, I intend to try to be faithful.... What does that mean? To love my country in my own way as you loved it in your way. And to make this love work. To look at the young people and be faithful to them. Besides that I shall do my work, the same work, my child, which you were denied. I want to honor God in my work, too, which means I want to be honest, true, and sincere.... When I try to be like that, dear Peter, I ask you then to be around me, help me, show yourself to me. I know you are there, but I see you only vaguely, as if you were shrouded in mist. Stay with me.... my love is different from the one which cries and worries and yearns.... But I pray that I can feel you so close to me that I will be able to make your spirit.

(4) Käthe Kollwitz, diary entry (13th June, 1916)

I have never been without your love, and because of it we are now so firmly linked after twenty-five years. Karl, my dear, thank you. I have so rarely told you in words what you have been and are to me. Today I want to do so, this once. I thank you for all you have given me out of your love and kindness. The tree of our marriage has grown slowly, somewhat crookedly, often with difficulty. But it has not perished. The slender seedling has become a tree after all, and it is healthy at the core. It bore two lovely, supremely beautiful fruits.

From the bottom of my heart I am thankful to the fate which gave us our children and in them such inexpressible happiness.

(5) Käthe Kollwitz, letter to Vorwarts (October, 1918)

In the Vorwaerts of October 22 Richard Dehmel published a manifesto entitled Sole Salvation. He appeals to all fit men to volunteer. If the highest defense authorities issued a call, he thinks, after the elimination of the "poltroons" a small and therefore more select band of men ready for death would volunteer, and this band could save Germany's honor.

I herewith wish to take issue with Richard Dehmel's statement. I agree with his assumption that such an appeal to honor would probably rally together a select band. And once more, as in the fall of 1914, it would consist mainly of Germany's youth - what is left of them. The result would most probably be that these young men who are ready for sacrifice would in fact be sacrificed. We have had four years of daily bloodletting - all that is needed is for one more group to offer itself up, and Germany will be bled to death. All the country would have left would be, by Dehmel's own admission, men who are no longer the flower of Germany. For the best men would lie dead on the battlefields. In my opinion such a loss would be worse and more irreplaceable for Germany than the loss of whole provinces.

We have learned many new things in these four years. It seems to me that we have also learned something about the concept of honor. We did not feel that Russia had lost her honor when she agreed to the incredibly harsh peace of Brest-Litovsk. She did so out of a sense of obligation to save what strength she had left for internal reconstruction. Neither does Germany need to feel dishonored if the Entente refuses a just peace and she must consent to an imposed and unjust peace. Then Germany must be proudly and calmly conscious that in so consenting she no more loses her honor than an individual man loses his because he submits to superior force. Germany must make it a point of honor to profit by her hard destiny, to derive inner strength from her defeat, and to face resolutely the tremendous labors that lie before her.

I respect the act of Richard Dehmel in once more volunteering for the front, just as I respect his having volunteered in the fall of 1914. But it must not be forgotten that Dehmel has already lived the best part of his life. What he had to give - things of great beauty and worth - he has given. A world war did not drain his blood when he was twenty.

But what about the countless thousands who also had much to give-other things beside their bare young lives? That these young men whose lives were just beginning should be thrown into the war to die by legions - can this really be justified?

(6) Agnes Smedley, Germany's Artist of the Masses (September, 1925)

She is now fifty-eight years of age, and remains unimpressed by attentions, medals, books, or professorships. Her ceaseless physical activity would lead one to believe she is no more than forty. Her life is as simple as that of an ordinary working woman, and she still lives in the workers' section of North Berlin. Her gaze is direct and her voice startlingly strong, and she sees far beyond those who bring her superficial, external tributes or who try to use her for their own propaganda purposes. She is a silent person, but when she speaks it is with great directness, without trimmings to suit the prejudices of her hearers. Many people, before meeting her, expect to see a bitter woman. But they see, instead, a kind - very kind - woman to whom love - strong, love, however - is the rule of life.

(7) Martha Kearns, Käthe Kollwitz (1976)

The influence of her mother upon Käthe's character and work had been profound. Like her mother - and like herself - the women Kollwitz portrayed are loving and strong. It is the women in her work-most often mothers - who carry the drama. With few exceptions, men participate in Kollwitz' emotional scene as adjuncts, as fathers and husbands in the background. It is the women who confront the crises head on: they brave war, poverty, homelessness, their husband's unemployment, servitude, widowhood, sexual abuse, and their children's hunger. In the darkest despair, the women continue to support the life of others. Kollwitz's women are subjected but not humiliated, victimized by force but not weak; they have the power - through strong love - to face and endure their trials. Her women are heroic in the epic of every day.

(8) Käthe Kollwitz, journal entry (June, 1926)

The cemetery is close to the highway.... The entrance is nothing but an opening in the hedge that surrounds the entire field. It was blocked by barbed wire which a friendly young man bent aside for us; then he left us alone. What an impression: cross upon cross.... on most of the graves there were low, yellow wooden crosses. A small metal plaque in the center gives the name and number. So we found our grave.... We cut three tiny roses from a flowering wild briar and placed them on the ground beside the cross. All that is left of him lies there in a row-grave. None of the mounds are separated; there are only the same little crosses placed quite close together.... and almost everywhere is the naked, yellow soil.... at least half the graves bear the inscription unknown German...

We considered where my figures might be placed... What we both thought best was to have the figures just across from the entrance, along the hedge.... Then the kneeling figures would have the whole cemetery before them... Fortunately no decorative figures have been placed in the cemetery, none at all. The general effect is of simple planes and solitude... Everything is quiet, but the larks sing gladly.

As we went on, we probably passed the very place where he fell, but here everything has been rebuilt... Everywhere there are traces of the war.... the ground is hollowed out by countless shellholes... In this place alone the Germans are said to have lost 200,000 men in the course of the four years. Their trenches and the Belgian trenches were sometimes separated by only twenty, even ten yards. They have been closed up now and life goes on; only the Belgian dugouts and trenches, those bowels of death as they call them, have been preserved and are a sort of place of pilgrimage for the Belgians...

The British and Belgian cemeteries seem brighter, in a certain sense more cheerful and cosy, more familiar than the German cemeteries. I prefer the German ones. The war was not a pleasant affair; it isn't seemly to prettify with flowers the mass deaths of all these young men. A war cemetery ought to be somber.

(9) Käthe Kollwitz, Arbeiters International Zeitung (October, 1927)

This is not the place for us to discuss why I am not a Communist. But it is the place for me to state that, as far as I am concerned, what has happened in Russia during the last ten years seems to be an event which both in stature and significance is comparable only with that of the great French Revolution. An old world, sapped by four years of war and undermined by the work of revolutionaries, fell to pieces in November 1917. The broad outline of a new world was hammered together. In an essay written during the early days of the Soviet Republic, Maksim Gorki speaks of "flying with one's soles turned upwards." I believe that I too can sense such flying in the gale inside Russia. For this flying of theirs, for the fervour of their beliefs, I have often envied the Communists.

(9) Kito Nedo, Käthe Kollwitz (18th July, 2017)

There aren’t many artists whose work can spark vehement political debate half a century after their death; Käthe Kollwitz, one of Germany’s most important artists of the early 20th century, has earned this unusual honor.

Back in 1993, Germany’s then-chancellor Helmut Kohl (who passed away last month) ordered a large-scale bronze copy of her Pietà sculpture Mother With Her Dead Son to be installed in the Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s New Guardhouse, located on Berlin’s main avenue, Unter den Linden. It was only a couple of years after German reunification, and the Guardhouse - which in the 1930s served as a memorial to victims of the Great War, and was turned into a Memorial to the Victims of Fascism and Militarism by the East-German government in 1960 - was again renamed as the Central Memorial of the Federal Republic of Germany to the Victims of War and Dictatorship. The memorial immediately became the subject of heated debates, not in the least due to the choice of artwork.

Astonishingly enough, by opting for a sculpture by Kollwitz, Kohl successfully challenged the left for one of its identificatory figures. For decades in West Germany, placards with Kollwitz’s famous No More War! poster from the 1920s were a common sight at peace demonstrations. In East Germany, the artist (who died in April 1945, a few days before the end of WWII) was venerated as a national hero and thus used for political ends - undeterred by regular references in the West to her diaries, in which she argues for the political independence of art.

In 1919 she became the first woman in the Modern era to be elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts, later becoming the first woman professor there (she took up teaching in 1928). By this time, having lost her son Peter in WWI in 1914, she was already a public figure. With her political art, often disseminated in newspapers and on posters, she sought to reach a broad audience, and in this she succeeded. So much so in fact that in 1933, the Nazis forced her to resign from the Academy and effectively prevented her from exhibiting her work.

By the mid-1950s, just 10 years after her death, her socially engaged art was no longer much valued in the art world. The American art theorist Lucy Lippard once explained this disappearance from the radar by referring to Kollwitz’s closeness to real life that was incompatible with the artist clichés of the Post-War period: Rather than presenting herself as a lofty genius or an outsider, she worked on themes such as poverty, hunger, motherhood, death, or bereavement.

In 1967, the centenary of her birth, German critic Gottfried Sello summed up this approach to her work in the West-German weekly Die Zeit, writing, “In spite of her progressive ideas, Kollwitz is an arch-conservative artist.” But what does this perceived conservatism mean? Perhaps that in their complex linking of history, aesthetics, and politics, her drawings, etchings, lithographs, woodcuts, and sculptures can be read in very different, sometimes contradictory ways: German conservatives admire her artistic craftsmanship and, perhaps tainted by ambiguous nostalgia, the fact that she is a witness of the period of the German Kaiser. Meanwhile, the Left celebrates her anti-war stance and the class-consciousness reflected in her art. And the feminist movement identifies Kollwitz as a role model who challenged the misogyny in the art institutions of the time and helped to pave the way for later generations of women artists.

For the Düsseldorf-based artist Katharina Sieverding, winner of the 2017 Käthe Kollwitz Prize awarded by Berlin’s Academy of Arts, Kollwitz’s work is characterized by a high degree of empathy. “Kollwitz addressed social and political issues and she wanted her art to make an impact,” says Sieverding. “Affect plays an important part here. And self-determination played a central role in her life and work.” In Sieverding’s view, one reason for the distanced response from within contemporary art is the way Kollwitz’s oeuvre was overshadowed by the reception of the artist as a person.

Today, art’s status as a viable form of protest and resistance is being critically challenged more rigorously than it has been for a long time, but so far, Kollwitz has been strangely absent from this discussion. Unlike similarly politically progressive and articulate artists like Corita Kent (1918–1986) and Alice Neel (1900–1984), or Kollwitz’s coeval, the American painter Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944), the familiar art-world dynamic of obscurity, rediscovery, and reevaluation doesn’t seem to be so easily set in motion for Kollwitz.