Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels, the son of Fritz Goebbels and Katharina Odenhausen, was born in Rheydt, Germany, on 29th October, 1897. His father was a bookkeeper at the United Wick Factories. Joseph was the third son born to the couple. Two brothers, Konrad and Hans, were two and four years older respectively and two sisters, Elizabeth and Maria, were born later.

Fritz Goebbels continued to make progress in his career and soon after Joseph was born, he was promoted and now earned 2,100 marks a year, with a one-time holiday bonus of 250 marks. Joseph Goebbels later described him as a "starched-collar proletarian". He had a difficult relationship with his father and disliked his "Spartan discipline" and only loved him "as he understands love". He was much closer to his mother who lavished love on her son the love "she withheld from her husband".

Soon after his birth, Joseph Goebbels nearly died of pneumonia. Although he finally recovered he did not enjoy good health. At the age of three he contacted osteomyelitis. As Ralf Georg Reuth, the author of Joseph Goebbels (1993), pointed out: "For two years his family doctor and a masseur struggled to rid his right leg of intermittent paralysis. Finally they had to tell the despairing parents that Joseph's foot was 'lamed for life,' would fail to grow properly, and would eventually develop into a clubfoot. Fritz and Katharina Goebbels refused to accept this prognosis. They even arranged for Joseph to be seen by doctors at the University of Bonn's medical school, a step requiring great courage for people of their humble station.... Later, after the boy had hobbled around for some time with an ugly orthopedic appliance that was supposed to hold the paralyzed foot straight and provide support, the surgeons at the Maria-Hilf Hospital in Monchengladbach agreed to operate on the ten-year-old. The operation proved a failure, putting an end to any hopes that the child might be spared a clubfoot."

Childhood

Joseph Goebbels later wrote that because he "could no longer run and jump like them", and now his loneliness sometimes became a torment to him. "The thought that the others did not want him around for their games, that his solitude was not of his own choosing, made him truly lonely. And not only lonely - it also made him bitter. When he saw the others running about and leaping, he grumbled at his God, who had done ... this to him, he hated the others for not being like him, he mocked his mother for still loving a cripple like him."

Toby Thacker, the author of Joseph Goebbels: Life and Death (2009) argues: "After this (1907) he walked with a noticeable limp. It is reasonable to assume that he suffered insults from other children, and, in a society which exalted strong military virtues, that this might have caused particular anxiety. At any rate, Goebbels from a very young age was solitary and reclusive, keeping his own company, and becoming an intensive reader... This was an extraordinarily austere childhood, stamped by Roman Catholic piety and a rigorous adherence to Prussian values of thrift, discipline, and hard work. Literally every pfennig was counted in the household accounting, and from an early age Joseph was chosen as the child most likely to fulfil his parents' dreams of upward social mobility. This parental favour derived partly from his disability, but was also due to the academic and artistic potential he displayed from an early age."

Ralf Georg Reuth argues that "the suffering of the scrawny, awkward youth with the outsized head and the increasingly misshapen foot did not diminish when he started school in the spring of 1904. The other children disliked him because he kept his thoughts to himself and remained aloof. The teachers disliked him because he was a self-willed, 'precocious lad' whose diligence left something to be desired. Occasionally they would beat him - when he had not done his homework again or when he provoked them. That probably explains why he had mostly bad memories of elementary school, particularly of his teachers." Goebbels described one of his teachers as a "villain and a scoundrel who abused us children," whereas another "spewed out all kinds of ridiculous nonsense." He liked only one teacher, who "told stories with real gusto" that stimulated his imagination.

Joseph Goebbels at School

As a result of the operation on his foot he spent a long time in the hospital. During this period he developed an obsession with reading: "My first fairy tales.... These books awakened my joy in reading. From then on I devoured everything in print, including newspapers, even politics, without understanding the slightest thing." He also worked his way through the two-volume version of Meyer's encyclopedia that his father had purchased. "He soon realized that his physical disadvantages could be offset by excellence in learning. His sense of inferiority constantly drove him to overcompensate." He later wrote that he found it unbearable if anyone else knew more than he did, "for he fully expected the others to be cruel enough to exclude him intellectually as well." He explained that this thought "filled him with diligence and energy." His extensive reading eventually had an impact on his academic performance and he claims that he was now "top of the class".

His parents were very religious. However, his club-foot caused him to question the existence of God. "Why had God made him this way, so that people laughed at him and mocked him? Why was he not allowed to love himself and life as others did? Why did he have to feel hatred when he wanted and needed to feel love?" After receiving religious instruction by Johannes Mollen, the assistant priest of the parish, at the age of thirteen, he resolved to dedicate his life to God. This pleased his parents as they hoped the Church would pay for their son's university studies.

Joseph Goebbels first romantic attachment ended in disaster. Maria Liffers, was his older brother's girlfriend. He wrote her passionate letters that were found by Maria's parents. They visited the Goebbels home and told the family what had happened. This resulted in his brother, Hans Goebbels, threatening to cut his throat with a razor.

His next girlfriend was Lene Krage. He described her as "not intelligent" but "very beautiful for her years". When they first kissed he was "the happiest person in the world". He could not believe that this "poor cripple" had allowed him to kiss "this most beautiful girl". Krage was very fond of Joseph Goebbels and wrote to him saying "you deserve to be worshipped" and "I could fall into idolatry". His sexual desire for Krage caused him problems with his religious beliefs. He was disgusted with himself after he succumbed to the temptations of the flesh. He wrote that he could not understand how he could love a girl he found "stupid" and that his love for Krage "had something impure about it".

Joseph Goebbels and the First World War

Joseph Goebbels was seventeen on the outbreak of the First World War. He desperately wanted to join the German Army but was rejected for health reasons - he was under five feet tall with a bad limp. Goebbels wrote in a school essay: "The soldier who marches forth to offer his fresh young life for wife and child, hearth and home, village and fatherland, serves the fatherland in the most distinguished and honorable way." Louis L. Snyder has argued: "Throughout his life Goebbels suffered from what he regarded as the stigma of being unable to serve his country in time of war. He was always conscious of his deformity and physical inadequacy."

In a speech delivered at school on 21st March 1917, he told the audience that "the limbs of that great Germany upon which the entire world gazes with fear and admiration" and the current war was an attempt to "become the political and spiritual leader of the world". The speech concluded with a vision that melded religion and patriotism: "Thou sacred land of our fathers, stand fast in Thy hour of need and death... Thy heroic strength and shalt go forth victorious from the final struggle... We trust in the everlasting God, whose will it is that right shall prevail, and in whose hand the future lies... God bless our Fatherland."

In April 1917 enrolled at the University of Bonn. On the advice of Father Johannes Mollen he joined a Catholic students' association, Unitas Sigfridia. However, two months later he was called up for alternative military service. Goebbels returned to Rheydt where he became a desk soldier for the Fatherland Auxiliary. The following year Father Mollen arranged for Goebbels to return to university.

In May 1918 he met Anka Stalherm, a wealthy young woman studying law and economics. He immediately fell in love with the woman with the "extraordinary passionate mouth" and the "brown-blond hair" that lay "in a heavy coil on her marvelous neck." They gradually grew closer and became a couple. "Mine was a sense of fulfillment infinite and without measure." Their different backgrounds caused Goebbels problems: "Within it (the university) I was a pariah, an outlaw, who was merely tolerated, not because I achieved less or was less intelligent than the others, but simply because I lacked the money that flowed to the others so generously from their fathers' pockets."

Toby Thacker, the author of Joseph Goebbels: Life and Death (2009) argues: "She was not his first girlfriend, but this was his first important relationship with women. For all that biographers and historians have pictured Goebbels as a young man filled with repressed hatred because of his disability, he was clearly very able to attract women of his own age. From the age of 15 he was more or less continuously involved with one or more women in intimate relationships. His whole mood and outlook fluctuated in sympathy with the changing fortunes of these relationships, which were invariably stormy, interrupted by difficulties with money, and beset with jealousy and misunderstandings. Goebbels' relationship with Anka Stalherm was characterized, like those that followed, by alternating periods of blissful happiness and bitter reproach."

Anka's parents completely disapproved of the relationship. Her mother sent her to confession to rid herself of the sins she had committed with this "penniless cripple". In a letter to Anka, Joseph Goebbels told her that she should tell her mother this letter would be his last: "Perhaps she will forgive you then." His relationship with Anka made him more class-conscious. He became involved in discussions with trade unionists in Rheydt. He explained to Anka: "In this way one at least comes to understand the stirrings among the workers." He added that they have "various problems... really worth examining closely."

The German Revolution

On 11th November 1918, the German government signed the Armistice. Goebbels, like most people living in Germany, found the news shocking. Ralf Georg Reuth, the author of Joseph Goebbels (1993), has pointed out: "A number of factors made this event incomprehensible to many Germans: there had been talk of victory to the very last; no shots had been fired on German soil; and the German armies had proved victorious in the east and penetrated deep into the enemy territory in the west. Subsequent developments inside the Reich seemed even more difficult to grasp. Nothing remained of the sense of national unity invoked by Wilhelm II at the beginning of the war, when he had said he no longer saw political parties, only Germans. The kaiser abdicated the day the armistice was signed. In the days preceding his departure, German soldiers had mutinied."

Goebbels held right-wing nationalist views and was appalled when Social Democratic Party leader, Philipp Scheidemann, declared a republic in Berlin on 9th November, 1918. Shortly afterwards, Karl Liebknecht, leader of the Spartacus League, proclaimed a "free socialist republic". He noted in his memoirs, "Revolution. Revulsion." He wrote to his friend, Fritz Prang: "Don't you agree that the hour will again come when people will call out for spirit and strength in the lowly, insignificant horde of the masses? Let us wait this hour and not cease to arm ourselves for this struggle."

Goebbels and Anka Stalherm began to argue about politics. He wrote a letter to her in April 1920 where he expressed concern about the plight of the workers: "It is rotten and dismal that a world of so many hundred million people should be ruled by a single caste that has the power to lead millions to life or to death, indeed on a whim (for example imperialism in France, capitalism in England and North America, perhaps in Germany as well, etc.). This caste has spun its web over the entire earth; capitalism recognizes no national boundaries (witness the terrible, shameful conditions within German capitalism during the war, whose internationalism created a situation - evidence is available - in which, while battles raged, German prisoners of war in Marseilles were unloading German artillery pieces, marked with the names of German manufacturers, to be used to destroy German lives). Capitalism has learned nothing from recent events and wants to learn nothing, because it places its own interests ahead of those of the other millions. Can one blame those millions for standing up for their own interests, and only for those interests? Can one blame them for striving to forge an international community whose purpose is the struggle against corrupt capitalism? Can one condemn a large segment of the educated Sturmer youth for protesting against education's being made a commodity, inaccessible to those with the greatest ability? Is it not an abomination that people with the most brilliant intellectual gifts should sink into poverty and disintegrate, while others dissipate, squander, and waste the money that could help them... You say the old propertied class also worked hard for what it has. Granted, that may be true in many cases. But do you also know about the conditions under which workers were living during the period when capitalism 'earned' its fortune?"

As Ralf Georg Reuth, the author of Joseph Goebbels (1993), pointed out: "As If the difference in the lovers' backgrounds had often created a tension overcome by the euphoria of love, the gulf created by Goebbels's socialistic views now seemed impossible to bridge. Despite the revolutionary turmoil shaking the Reich to its foundations, Anka Stalherm remained true to her bourgeois origins. The world from which she came offered her every advantage. A lover who showed enthusiasm for the Red revolution and actually seemed happy that her sheltered existence was threatened by political terror could not but appear more and more alien to her."

Goebbels discovered that Anka was seeing another man. Dr. Georg Mumme, was a lawyer who lived in Freiburg. He wrote to her proposing they get engaged. "If you don't feel strong enough to say yes, we must go our separate ways." Anka rejected the offer and Goebbels noted in his diary: "Grim days. I shall be alone." Goebbels wrote another letter, this time threatening suicide. He told her that "I have suffered enough; how much more shall I have to suffer?" Anka replied that she promised she would remain faithful.

Joseph Goebbels also got into debt and could no longer afford his university fees. In October 1920 he decided to commit suicide. He drew up a will, in which he named his brother, Hans Goebbels, as his literary executor. He meticulously enumerated his few possessions - an alarm clock, a drawing, a few books, bequeathing them to friends and members of the family. He instructed Hans that "his wardrobe and other possessions not otherwise assigned" should be sold, and that his debts be paid off from the proceeds. He told Hans that Anka should burn his letters and any other writings: "May she be happy and get over my death.... I part gladly from this life, which for me has become a hell." When his father heard about the will he quickly told him he would borrow the money so that he could finish off his university studies. When he heard the news he withdrew his threat.

The following year Joseph Goebbels was offered a place studying for a PhD at Heidelberg University. Working under Professor Max von Waldberg, his dissertation subject was Wilhelm Schutz, a little-known member of the romantic school active as a dramatist in the first half of the nineteenth century. His oral examination took place on 16th November 1921. It was a success and he received his doctoral diploma and later noted that he had felt very proud when Waldberg called him "Herr Doktor" for the first time.

Joseph Goebbels and Gregor Strasser

Goebbels spent the next ten years writing novels, plays and poems. When he failed to find a publisher for his work he developed the theory that this was because the publishing companies were owned by Jews. He was also rejected as a reporter by the newspaper Berliner Tageblatt. Goebbels joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) in 1926.

Joseph Goebbels became a follower of Gregor Strasser, who had joined forces with his brother, Otto Strasser, to establish the Berliner Arbeiter Zeitung, a left-wing newspaper, that advocated world revolution. It also supported Lenin and the Bolshevik government in the Soviet Union. In one speech Strasser argued: "The rise of National Socialism is the protest of a people against a State that denies the right to work. If the machinery for distribution in the present economic system of the world is incapable of properly distributing the productive wealth of nations, then that system is false and must be altered. The important part of the present development is the anti-capitalist sentiment that is permeating our people."

Ernst Hanfstaengel has claimed that Adolf Hitler was deeply jealous of Gregor Strasser. "He was the one potential indeed actual rival within the party. He had made the Rhineland his fief. I remember during one tour through the Ruhr towns seeing Strasser's name plastered up against the wall of every railway underpass. He was obviously quite a figure in the land. Hitler looked away."

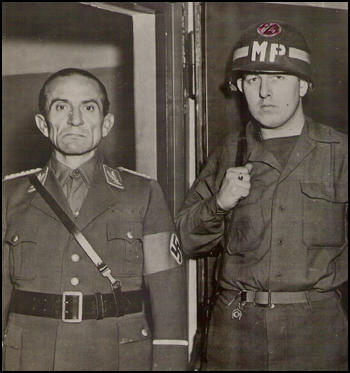

Rudolf Olden, the author of Hitler the Pawn (1936) has pointed out: "Gregor Strasser had discovered and brought out Dr. Goebbels, an unsuccessful writer. It was as Strasser's Socialist confederate that he first approached Hitler, and, immediately understanding on which side the balance of power was tipped, he went with colours flying over to the stronger battalions. Against his glowing ambitions, he had to set the obstacles nature had placed in his way. A dwarf, with a club foot and the dark, wrinkled face of a seven-months child-what had he to look for in circles where blond Nordic heroes were worshipped and idolised? But the little man was clever, adaptable and tough, and so he succeeded in making his way."

On 14th February, 1926, at the NSDAP annual conference, Strasser called for the destruction of capitalism in any way possible, including cooperation with the Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union. At the conference Joseph Goebbels supported Strasser but once he realised the majority supported Adolf Hitler over Strasser, he changed sides. From this point on Strasser began to call Goebbels "the scheming dwarf".

Goebbels described one of their first meetings with Hitler in his diary: "Shakes my hand. Like an old friend. And those big blue eyes. Like stars. He is glad to see me. I am in heaven. That man has everything to be king." Hitler admired Goebbels' abilities as a writer and speaker. They shared an interest in propaganda and together they planned how the NSDAP would win the support of the German people.

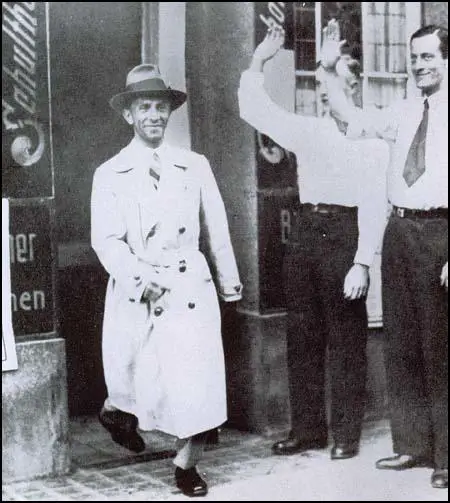

Joseph Goebbels edited Der Angriff (The Attack) and used the daily newspaper to promote the idea of German nationalism. He also became one of the NSDAP's most important speakers. Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "In public speaking he showed himself, with his deep, booming voice, to be almost the equal of Hitler. At mass meetings and demonstrations he hurled sarcasm and insults at the Berlin city government, Communists and Jews. The little man with the long nose and glittering eyes, always wearing a trench coat too big for him, won attention for himself, for Hitler, and for the party."

Hans Schweitzer was placed in charge of the poster campaign promoting the newspaper. According to Ralf Georg Reuth, the author of Joseph Goebbels (1993): "One trademark of Der Angriff was the caricatures by Hans Schweitzer... Goebbels's editorials and 'Political Diary,' combined with Schweitzer's caricatures, created a form of 'integrated political agitation' that in his eyes set Der Angriff apart from all the other papers in Berlin. Goebbels considered its propaganda effect 'irresistible,' with word and image serving 'not to convey information but to spur, incite, drive' the reader to action."

In a speech on 9th January, 1928 Goebbels said: "To attract people, to win over people to that which I have realised as being true, that is called propaganda. In the beginning there is the understanding, this understanding uses propaganda as a tool to find those men, that shall turn understanding into politics…. Propaganda should be popular, not intellectually pleasing. It is not the task of propaganda to discover intellectual truths."

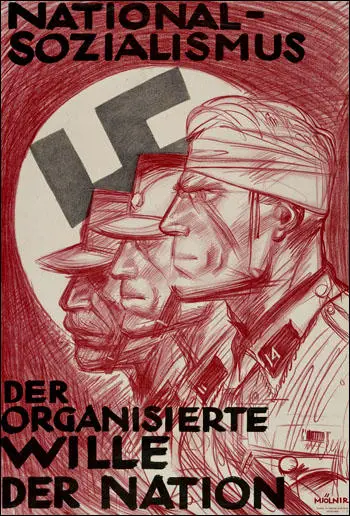

Adolf Hitler became aware of Schweitzer's abilities and he designed several posters for his 1932 presidential campaign. This included his National-Sozialismus and Our Last Hope - Hitler. Anthony Rhodes has argued that "his poster of the three Storm Troopers' heads is quintessential Nazi propaganda - simple, emotional, powerful." It reflected Hitler's idea that "by the masses, brutality and physical force are admired". Goebbels once said, "What lengthy speeches failed to do, Mjölnir did in a second through the glowing fanaticism of his powerful art."

Joseph Goebbels elected to the Reichstag

In 1928 Goebbels, Hermann Goering and ten other members of the Nazi Party were elected to the Reichstag. Soon afterwards Goebbels became the party's Propaganda Leader. Hitler was impressed by Goebbels work. He wrote in 1930: "Years ago I dispatched you, dear Dr. Goebbels, to the most difficult post in the Reich, in hopes that your energy and vigor would succeed in creating a tight, unified organization. You have fulfilled this task in such a way that you are assured of the movement's gratitude and my own highest recognition."

Magda Quandt began attending meetings of the Nazi Party. After hearing Goebbels and Adolf Hitler make speeches, she became a member on 1st September 1930. Later that year she went to work for Goebbels. According to Ralf Georg Reuth, the author of The Life of Joseph Goebbels (1993): "Magda Quandt fascinated him. Elegant in appearance and calmly assertive in bearing, she embodied a world that had hitherto remained in Goebbels's inner circle... She had grown up in very comfortable circumstances and had graduated from a convent school." However, Magda's parents both disliked him intensely and she came under "horrendous pressure" to break off the relationship.

Joseph Goebbels marries Magda Quandt

Goebbels married Magna on 19th December 1931, in Mecklenburg, with Hitler as a witness. Goebbels spoke about her "entrancing beauty" and her "clever, realistic sense of life". Goebbels claimed that together they spent "completely contented" evenings, after which he was "almost in a dream... so full of fulfilled happiness". Over the next few years they had six children: Helga, Hildegard, Helmut, Holdine, Hedwig and Heidrun.

Magda suffered from poor health and on 23rd January, 1933 she was hospitalized. He wrote in his diary: "God keep this woman for me. I can not live without her." Later he added: "To the clinic. Magda much better. The fever has abated. She is so happy that I am there. We talk much of our love, and how good we will be to one another, when she is healthy again. I have grown so with Magda, that I really can not exist without her."

Magda suffered from poor health and on 23rd January, 1933 she was hospitalized. He wrote in his diary: "God keep this woman for me. I can not live without her." Later he added: "To the clinic. Magda much better. The fever has abated. She is so happy that I am there. We talk much of our love, and how good we will be to one another, when she is healthy again. I have grown so with Magda, that I really can not exist without her."

Minister for Public Enlightenment

When Adolf Hitler became chancellor in January, 1933, he appointed Goebbels as Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Goebbels commented on March, 1933: "The best propaganda is that which, as it were, works invisibly, penetrates the whole of life without the public having any knowledge of the propagandistic initiative."

Richard Evans, the author of The Third Reich in Power (2005), explained how he took over the German film industry: "By 1936 it was funding nearly three-quarters of all German feature films, and was not afraid to withhold support from producers of whose projects it did not approve. Meanwhile, the Propaganda Ministry's control over the hiring and firing of people in all branches of the film industry had been cemented by the establishment of the Reich Film Chamber on 14 July 1933, headed by a financial official who was directly responsible to Goebbels himself. Anyone employed in the film industry was now obliged to become a member of the Reich Film Chamber, which organized itself into ten departments covering every aspect of the movie business in Germany. The creation of the Reich Film Chamber in 1933 was a major step towards total control. The next year, Goebbels's hand was further strengthened by a crisis in the finances of the two biggest film companies, UFA and Tobis, which were effectively nationalized.... Financial control was backed by legal powers, above all through the Reich Cinema Law, passed on 16 February 1934. This made pre-censorship of scripts mandatory. It also merged the existing film censors' offices, created in 1920, into a single bureau within the Propaganda Ministry. And as amended in 1935 it gave Goebbels the power to ban any films without reference to these institutions anyway.".

Joseph Goebbels told people his limp was the result of a wound suffered while fighting in the First World War. The historian, Louis L. Snyder has pointed out: "Despite his piercing intelligence and demagogic brilliance, he resented the stares and the suspected comments. It was especially galling for this crippled little man, with his slight frame and black hair... to appear in public and preach the virtues of a tall, healthy, blue-eyed Aryan race. He was aware that his well-built, feeble-brained comrades... ridiculed him behind his back. It is probable that deep-rooted hatreds stemmed in large part from his resentment because of his physical condition."

Traudl Junge, the author of To The Last Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary (2002) claims that women in the ministry found Goebbels attractive: "Goebbels brought verve and wit into the conversation. He wasn't at all handsome, but I could see why the girls in the Reich Chancellery ran to the windows to see the Propaganda Minister leave his Ministry, but took hardly any notice of Hitler.... The ladies at the Berghof positively flirted with Hitler's Minister too. He really did have a delightfully entertaining manner, and his shafts of wit were well aimed, although mostly at other people's expense."

Goebbels began to take a close interest in Lida Baarová, a young actress from Prague. Goebbels' biographer, Ralf Georg Reuth, the author of Joseph Goebbels (1993), has argued: "Goebbels showed his interest in the actress more and more obviously, and the ambitious young woman certainly did not object to the attentions of the man who carried the most weight in the German film industry... A dark-haired Slavic type, more like the femmes fatales officially frowned upon by the regime... Lida Baarová in looks was the exact opposite of Magda Goebbels." Lída Baarová said of Goebbels: "There's no doubt that Goebbels was an interesting character, a charming and intelligent man and a very good storyteller. You could guarantee that he would keep a party going with his little asides and jokes."

The relationship upset Adolf Hitler. According to Heinz Linge, Hitler's valet: "Hitler acknowledged the value of Goebbels as a propagandist to his closest circle, where he often would not spare the blushes in being blunt. On the other hand, he did not always approve of Goebbels's private life. The many little stories circulating about Goebbels concerned him deeply. Because radio, the theatre and the film industry all came under the propaganda Ministry, Goebbels often came into contact with actresses and other female artistes upon whom the minister - and perhaps even more so the genial talker who could help one get ahead in one's career - often made a lasting impression. I often noticed how artistes and starlets of film and theatre would swarm around him, rivals for his favour.... A scandal erupted when the beautiful Czech film star Lida Baarova entered his adoring circle. She exercised such a spell over Goebbels that he quite lost his head and almost wrecked his until then happy marriage with wife Magda... Frau Goebbels wanted a divorce and to emigrate to Switzerland, causing Hitler to envisage for himself a major scandal. He decided to attempt a reconciliation of the couple and invited them both to Obersalzberg. There he received them separately. In individual conversations he explained to them that they must relegate their personal interests to those of the state. The separation was prevented. In the Berghof Great Hall he made them both promise to remain loyal to each other from now on. Happy at having resolved the crisis he brought the reconciled couple himself to the NSDAP guesthouse on Obersalzberg". After her relationship ended with Goebbels, Lida Baarová had difficulty making films. In 1938 her film, A Prussian Love Story, was banned and she fled to Prague

Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler

Albert Speer later commented on Goebbels relationship with Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Goering: "After 1933 there quickly formed various rival factions that held divergent views, spied on each other, and held each other in contempt. A mixture of scorn and dislike became the prevailing mood within the party. Each new dignitary rapidly gathered a circle of intimates around him. Thus Himmler associated almost exclusively with his SS following, from whom he could count on unqualified respect. Goering also had his band of uncritical admirers, consisting partly of members of his family, partly of his closest associates and adjutants. Goebbels felt at ease in the company of literary and movie people. Hess occupied himself with problems of homeopathic medicine, loved chamber music, and had screwy but interesting acquaintances. As an intellectual Goebbels looked down on the crude philistines of the leading group in Munich, who for their part made fun of the conceited academic's literary ambitions. Goering considered neither the Munich philistines nor Goebbels sufficiently aristocratic for him and therefore avoided all social relations with them; whereas Himmler, filled with the elitist missionary zeal of the SS felt far superior to all the others."

Traudl Junge claims that Joseph Goebbels did not like Himmler: "So the chatter round the table went on, and Goebbels aimed his sallies, which hit their mark and were not returned. Curiously enough, Himmler and Goebbels entirely ignored each other. It wasn't too obvious, but still you couldn't help noticing that their relationship was a superficial veneer of civility. The two of them met relatively seldom; they didn't have much to do with each other, and were not, like the warring Bormann brothers, kept on the same leash by their master. The hostility between the Bormanns was so habitual and firmly established that they could stand side by side and ignore each other entirely. And when Hitler gave a letter or request to the younger Bormann to be passed on to the Reichsleiter, Albert Bormann would go out, find an orderly, and the orderly would pass instructions on to his big brother even if they were both in the same room. The same thing happened in reverse, and if one Bormann told a funny story at table all the rest of the company would roar with laughter, while his brother just sat there ignoring them and looking deadly serious. I was surprised to find how used Hitler had become to this state of affairs. He took no notice of it at all. Unfortunately I never managed to find out the reason for their enmity. I think there was a woman behind it. Or perhaps those two fighting cocks had long ago forgotten the reason themselves?"

Ernst Hanfstaengel blamed Goebbels for being a bad influence on Adolf Hitler. "The evil genius of the second half of Hitler's career was Goebbels. I always likened this mocking, jealous, vicious, satanically gifted dwarf to the pilot-fish of the Hitler shark. It was he who finally turned Hitler fanatically against all established institutions and forms of authority. He was not only schizophrenic but schizopedic, and that was what made him so sinister."

Second World War

During the Second World War Goebbels played an important role in building up hatred for the allies. He had little confidence in the abilities of other ministers in the government and made attempts to have Joachim von Ribbentrop dismissed from office.

Goebbels encouraged Hitler to invade the Soviet Union. He wrote in July 1941: "The Führer thinks that the action will take only 4 months; I think - even less. Bolshevism will collapse as a house of cards. We are facing an unprecedented victorious campaign. Cooperation with Russia was in fact a stain on our reputation. Now it is going to be washed out. The very thing we were struggling against for our whole lives, will now be destroyed. I tell this to the Führer and he agrees with me completely."

Joseph Goebbels also advocated terror bombing of Britain: "He (Hitler) said he would repeat these raids night after night until the English were sick and tired of terror attacks. He shares my opinion absolutely that cultural centres, health resorts and civilian resorts must be attacked now. There is no other way of bringing the English to their senses. They belong to a class of human beings with whom you can only talk after you have first knocked out their teeth."

Joseph Goebbels and the Jewish Question

Goebbels argued at a meeting on 12th November 1938: "I deem it necessary to issue a decree forbidding the Jews to enter German theaters, movie houses and circuses. I have already issued such a decree under the authority of the law of the chamber for culture. Considering the present situation of the theaters, I believe we can afford that. Our theaters are overcrowded, we have hardly any room. I am of the opinion that it is not possible to have Jews sitting next to Germans in varieties, movies and theaters. One might consider, later on, to let the Jews have one or two movie houses here in Berlin, where they may see Jewish movies. But in German theaters they have no business anymore. Furthermore, I advocate that the Jews be eliminated from all positions in public life in which they may prove to be provocative. It is still possible today that a Jew shares a compartment in a sleeping car with a German. Therefore, we need a decree by the Reich Ministry for Communications stating that separate compartments for Jews shall be available; in cases where compartments are filled up, Jews cannot claim a seat. They shall be given a separate compartment only after all Germans have secured seats. They shall not mix with Germans, and if there is no more room, they shall have to stand in the corridor."

It has been argued by Laurence Rees, the author of The Nazis: A Warning from History (2005) has argued Goebbels took a hard-line of German Jews: "Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda Minister and Gauleiter of Berlin, was one of those who took the lead that summer (1941) in pushing for the Jews of Berlin to be forcibly deported East. At a meeting on 15 August Goebbels' state secretary, Leopold Gutterer, pointed out that of the 70,000 Jews in Berlin only 19,000 were working (a situation, of course, that the Nazis had created themselves by enforcing a series of restrictive regulations against German Jews). The rest, argued Gutterer, ought to be "carted off to Russia... best of all actually would be to kill them." And when Goebbels himself met Hitler on 19 August he made a similar case for the swift deportation of the Berlin Jews. Dominant in Goebbels' mind was the Nazi fantasy of the role that German Jews had played during World War I. While German soldiers had suffered at the front line, the Jews had supposedly been profiting from the bloodshed back in the safety of the big cities (in reality, of course, German Jews had been dying at the front in proportionately the same numbers as their fellow countrymen). But now, in the summer of 1941, it was obvious that Jews remained in Berlin while the Wehrmacht were engaged in their brutal struggle in the East - what else could they do, since the Nazis had forbidden German Jews to join the armed forces?"

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary on 27th March, 1942: "The Jews are now being forced eastwards from the General Government, commencing with Lublin. A pretty barbaric method, not to be described in detail, is being used here, and not much of the Jews themselves remains afterwards.... A judicial sentence is being carried out against the Jews which is certainly barbaric, but which they have fully deserved. What the Führer prophesied in the eventuality of the Jews bringing about a new world war has begun to be realised in the most terrible fashion. In these matters, one cannot let sentimentality prevail. If we did not defend ourselves against them, the Jews would exterminate us. It is a life and death struggle between the Aryan race and the Jewish bacillus. No other government and no other regime could muster the strength for a general solution of this question. Here too, the Führer is the untiring advocate and champion of a radical solution, which the situation demands, and which therefore appears inevitable. Thank God the war affords us a series of opportunities which were denied us in peacetime. We must make use of them. The ghettos in the towns of the General Government which have been made vacant can now be filled with the Jews expelled from the Reich, and then the process can be repeated after a certain time."

The Death of Joseph Goebbels

When the Red Army made advances into Nazi Germany, Hitler invited Goebbels and his family to move into his Führerbunker in Berlin. Joseph Goebbels wrote to his stepson, Helmut Quandt, on 28th April, 1945: "We are now confined to the Führer's bunker in the Reich Chancellery and are fighting for our lives and our honour. God alone knows what the outcome of this battle will be. I know, however, that we shall only come out of it, dead or alive, with honour and glory. I hardly think that we shall see each other again. Probably, therefore, these are the last lines you will ever receive from me. I expect from you that, should you survive this war, you will do nothing but honour your mother and me. It is not essential that we remain alive in order to continue to influence our people. You may well be the only one able to continue our family tradition. Always act in such a way that we need not be ashamed of it... Farewell, my dear Harald. Whether we shall ever see each other again is in the lap of the gods. If we do not, may you always be proud of having belonged to a family which, even in misfortune, remained loyal to the very end to the Führer and his pure sacred cause."

Rochus Misch, Hitler's bodyguard, claims that Goebbels told him: “Well, Misch, we knew how to live. Now we know how to die." Misch added: "Then he and Frau Goebbels processed arm-in-arm up the stairs to the garden... The children were prepared for their deaths in my work room. Their mother combed their hair - they were all dressed in white nightshirts - and then she went up with the children. Dr Nauman told me that Dr Ludwig Stumpfegger would give the kids 'candy water’. I realised what was going to happen immediately. I had seen Dr Stumpfegger successfully test poison on Blondi, the Führer’s dog.”

Heinz Linge, the author of With Hitler to the End (1980), was in the Fuhrer-bunker: "For Dr Joseph Goebbels, the new Reich Chancellor, it was not apparent until now that he and his wife Magda would commit suicide in Berlin this same day. After the experiences of recent days and weeks hardly anything could shock us men any more, but the women, the female secretaries and chambermaids were 'programmed' differently. They were fearful that the six beautiful Goebbels children would be killed beforehand. The parents had decided upon this course of action. Hitler's physician Dr Stumpfegger was to see to it. The imploring pleas of the women and some of the staff, who suggested to Frau Goebbels that they would bring the children - Helga, Holde, Hilde, Heide, Hedda and Helmut - out of the bunker and care for them, went unheard. I was thinking about my own wife and children who were in relative safety when Frau Goebbels came at 1800 hours and asked me in a dry, emotional voice to go up with her to the tormer Fuhrer-hunker where a room had been set up for her children. Once there she sank down in an armchair. She did not enter the children's room, but waited nervously until the door opened and Dr. Stumpfegger came out. Their eyes met, Magda Goebbels stood up, silent and trembling. When the SS doctor nodded emotionally without speaking, she collapsed. It was done. The children lay dead in their beds, poisoned with cyanide. Two men of the SS bodyguard standing near the entrance led Frau Goebbels to her room in the Fuhrer-bunker."

On 1st May, 1945, Joseph Goebbels, his wife and six children, committed suicide. According to Ralf Georg Reuth, the author of Goebbels (1995): "The last details regarding the deaths of Joseph and Magda Goebbels will probably always remain unclear. It is certain that they poisoned themselves with cyanide, but it is not known whether Goebbels also shot himself in the head. Nor do we know whether they died in the bunker or outside at the emergency exit, where the Soviets found their bodies."

Primary Sources

(1) Ralf Georg Reuth, Joseph Goebbels (1993)

As a young child he (Joseph Goebbels) almost died of pneumonia, accompanied by "terrible fever hallucinations." He survived but remained a"sickly little fellow." Shortly after the turn of the century, Joseph contracted osteomyelitis, one of the "decisive events" of his childhood, as he later called it." He describes in his "Memories" how, after a long walk with the family, the old "foot problem" that they had thought cured manifested itself again, with severe pain. For two years his family doctor and a masseur struggled to rid his right leg of intermittent paralysis. Finally they had to tell the despairing parents that Joseph's foot was "lamed for life," would fail to grow properly, and would eventually develop into a clubfoot. Fritz and Katharina Goebbels refused to accept this prognosis. They even arranged for Joseph to be seen by doctors at the University of Bonn's medical school, a step requiring great courage for people of their humble station. But even these experts merely "shrugged their shoulders." Later, after the boy had hobbled around for some time with an ugly orthopedic appliance that was supposed to hold the paralyzed foot straight and provide support, the surgeons at the Maria-Hilf Hospital in Monchengladbach agreed to operate on the ten-year-old. The operation proved a failure, putting an end to any hopes that the child might be spared a clubfoot.

Joseph Goebbels's deeply religious parents, especially his mother, viewed his misfortune as a curse on the family. In their world a physical defect was a punishment inflicted by God. Katharina Goebbels would often take her "Juppchen" by the hand and go to St. Mary's, where she would kneel beside him and pray fervently that the Lord might give the child strength and turn this evil away from him and the family. For fear of the neighbors' gossip, she attributed Joseph's deformity not to an illness but to an accident; she claimed she had picked the child up from a bench without noticing that his foot was caught between the slats. Even so, shortly after the boy fell ill, people had begun to remark that he "didn't take after the rest of the family."

(2) Toby Thacker, Joseph Goebbels: Life and Death (2009)

Our knowledge of this German childhood is though very speculative, and much of it has an anecdotal quality, inevitably, since it has been passed down orally.; We know that the young Joseph Goebbels suffered from an infantile paralysis of the right foot, and that after years of difficulty, his foot was operated on, unsuccessfully, in 1907. After this, he walked with a noticeable limp. It is reasonable to assume that he suffered insults from other children, and, in a society which exalted strong military virtues, that this might have caused particular anxiety. At any rate, Goebbels from a very young age was solitary and reclusive, keeping his own company, and becoming an intensive reader. In an account of his childhood and youth written in the summer of 1924, Goebbels himself described his life after the operation on his foot: "Childhood from then on pretty joyless. I could no longer join in the games of others. Became a solitary, lone wolf."

This was an extraordinarily austere childhood, stamped by Roman Catholic piety and a rigorous adherence to Prussian values of thrift, discipline, and hard work. Literally every pfennig was counted in the household accounting, and from an early age Joseph was chosen as the child most likely to fulfil his parents' dreams of upward social mobility. This parental favour derived partly from his disability, but was also due to the academic and artistic potential he displayed from an early age. As he neared adolescence, his parents took two notable steps: after scrimping and saving, they bought a piano for him to learn on, and in 1908 they entered him for the local Gymnasium, or grammar school. Goebbels later recounted how the neighbours all came out to watch as the piano was brought into the house, wondering where the Goebbels family had found the money for this "symbol of education and prosperity". The piano was installed in the parlour - which was otherwise reserved for important occasions or for respectable visitors - and young Joseph was now allowed to enter the room every day. In the winter months, if we are to believe his later reminiscence, he sat there playing the piano in a coat, hat, and scarf, only able to read the music if there was sufficient moonlight.

At the Gymmnsium, Goebbels was an unusually intense student, and he did exceptionally well, particularly in languages, the arts, and in history, where he was brought up on the nationalistic narratives consolidated since 1871 in the German educational system. His school reports, uncluttered with today's educational jargon, consistently described his progress in most subjects as "good" or "very good". From childhood Goebbels was a voracious reader, and from a young age he became also a writer.

(3) Rudolf Olden, Hitler the Pawn (1936)

Gregor Strasser, a chemist of Landshut in Bavaria, had borne the brunt of the agitation in North Germany. Even during Hitler's detention in the fortress he had made contacts in the North. An untiring worker, he made ample use of the free railway pass which he enjoyed as a member of the Reichstag, and travelled from place to place, appealing and collecting. In one year he made one hundred and eighty speeches and was for a long time better known and respected than Hitler among the volkisch groups on the further side of the Main. He had sold his pharmacy and invested his capital in politics. The first National Socialist papers that appeared in Berlin were started with his money.

Strasser was a useful helper, but an awkward subordinate. He considered himself a Socialist, although his Socialism was little else than Bavarian self-assurance and middle-class aversion to the " big noises." At one time something that looked very much like a conflict of opposing schools of thought existed in the National Socialist Party...Strasser had discovered and brought out Dr. Goebbels, an unsuccessful writer. It was as Strasser's Socialist confederate that he first approached Hitler, and, immediately understanding on which side the balance of power was tipped, he went with colours flying over to the stronger battalions. Against his glowing ambitions, he had to set the obstacles nature had placed in his way. A dwarf, with a club foot and the dark, wrinkled face of a seven-months child-what had he to look for in circles where blond Nordic heroes were worshipped and idolised? But the little man was clever, adaptable and tough, and so he succeeded in making his way.

It is possible that he really admires Hitler as his ideal, for he shares his most prominent quality: the instinct for power. However, it was certainly not admiration but downright policy that made him write to Hitler: "Before the Court in Munich, you grew in our minds to the stature of a leader. The words you spoke there were the greatest uttered in Germany since Bismarck... It is the catechism of a new political faith, in the desperation of a crumbling, God-bereft world... Like every great leader, you grew with your task; you grew great as your task grew greater, until you became a miracle."

Hitler was far too receptive to flattery not to recognise the talents of the young doctor. He made Goebbels his district leader in Berlin. He deprived Strasser of the province he himself had founded, appointed him "Director of Organisation for the Reich" and kept him under his eye. Rohm's affectionate friendship for Hitler survived the meanest treatment unscathed; Gregor Strasser likewise, in spite of all their differences, remained firm in his personal devotion to the Leader.

At the Party Congress which followed the alliance with Hugenberg, Strasser made himself the mouthpiece of the critics. Hugenberg's hopes of the alliance were his fears: the National Socialists would now no longer be able to fight against the "respectable" elements in the German Nationalist reaction; they would be overwhelmed by the others' superior financial strength; they would now be nothing but an appendage of the stronger party. He under-estimated Hitler. A man who, like an hysterical child, is only really alive when he is in the centre of the picture, does not easily become an "appendage." He did not understand Hitler either. He took the support of the masses for an end in itself. But Hitler thought of it only as the dowry he would contribute to the match he had at last arranged.

(4) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (24th March, 1933)

The Leader (Adolf Hitler) delivers an address to the German Reichstag. He is in good form. His speech is that of an expert statesman. Many in the House see him for the first time, and are much impressed by his demeanour. The leader of the Socialists, Wels, actually returns a reply which is one long woeful tale of one who arrives too late. All we have accomplished the Social Democrats had wanted to do. Now they complain of terrorism and injustice. When Wels ends, the Leader mounts the platform and demolishes him. Never before has anyone been so thoroughly defeated. The Leader speaks freely and well. The House in in an uproar of applause, laughter, and enthusiasm. An incredible success!

The Zentrum (Centre Party) and even the Party of the State (Staatspartei), affirm the law of authorization. It is valid for four years and guarantees freedom of action to the Government. It is accepted by a majority of four to five; only the Socialists vote against it. Now we are also constitutionally masters of the Reich.

(5) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (1st April, 1933)

The boycott against the international atrocity propaganda has burst forth in full force in Berlin and the whole Reich. I drive along the Tauentzien Street in order to observe the situation. All Jewish businesses are closed. SA men are posted outside their entrances. The public has everywhere proclaimed its solidarity. The discipline is exemplary. An imposing performance! It all takes place in complete quiet; in the Reich too.

In the afternoon 150,000 Berlin workers marched to the Lustgarten, to join us in the protest against the incitement abroad. There is indescribable excitement in the air. The press is already operating in total unanimity. The boycott is a great moral victory for Germany. We have shown the world abroad that we can call up the entire nation without thereby causing the least turbulence or excesses. The Fuhrer has once more struck the right note. At midnight the boycott will be broken off by our own decision. We are now waiting for the resultant echo in the foreign press and propaganda.

(6) Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (1970)

After 1933 there quickly formed various rival factions that held divergent views, spied on each other, and held each other in contempt. A mixture of scorn and dislike became the prevailing mood within the party. Each new dignitary rapidly gathered a circle of intimates around him. Thus Himmler associated almost exclusively with his SS following, from whom he could count on unqualified respect. Goering also had his band of uncritical admirers, consisting partly of members of his family, partly of his closest associates and adjutants. Goebbels felt at ease in the company of literary and movie people. Hess occupied himself with problems of homeopathic medicine, loved chamber music, and had screwy but interesting acquaintances.

As an intellectual Goebbels looked down on the crude philistines of the leading group in Munich, who for their part made fun of the conceited academic's literary ambitions. Goering considered neither the Munich philistines nor Goebbels sufficiently aristocratic for him and therefore avoided all social relations with them; whereas Himmler, filled with the elitist missionary zeal of the SS felt far superior to all the others. Hitler, too, had his retinue, which went everywhere with him. Its membership, consisting of chauffeurs, the photographer, his pilot, and secretaries, remained always the same.

(7) Richard Evans, The Third Reich in Power (2005)

By the second half of the 1930s, state control over the German film industry had become even tighter, thanks to the Film Credit Bank created in June 1933 by the regime to help film-makers raise money in the straitened circumstances of the Depression. By 1936 it was funding nearly three-quarters of all German feature films, and was not afraid to withhold support from producers of whose projects it did not approve. Meanwhile, the Propaganda Ministry's control over the hiring and firing of people in all branches of the film industry had been cemented by the establishment of the Reich Film Chamber on 14 July 1933, headed by a financial official who was directly responsible to Goebbels himself. Anyone employed in the film industry was now obliged to become a member of the Reich Film Chamber, which organized itself into ten departments covering every aspect of the movie business in Germany. The creation of the Reich Film Chamber in 1933 was a major step towards total control. The next year, Goebbels's hand was further strengthened by a crisis in the finances of the two biggest film companies, UFA and Tobis, which were effectively nationalized. By 1939, state-financed companies were producing nearly two-thirds of German films. A German Film Academy, created in 1938, now provided technical training for the next generation of film-makers, actors, designers, writers, cameramen and technicians, ensuring that they would work in the spirit of the Nazi regime. Financial control was backed by legal powers, above all through the Reich Cinema Law, passed on 16 February 1934. This made pre-censorship of scripts mandatory. It also merged the existing film censors' offices, created in 1920, into a single bureau within the Propaganda Ministry. And as amended in 1935 it gave Goebbels the power to ban any films without reference to these institutions anyway. Encouragement was to be provided, and cinemagoers' expectations guided, by the award of marks of distinction to films, certifying them as "artistically valuable", "politically valuable", and so on.

As Goebbels intended, there were plenty of entertainment films produced in Nazi Germany. Taking the categories prescribed by the Propaganda Ministry, fully 55 per cent of films shown in Germany in 1934 were comedies, 21 per cent dramas, 24 per cent political. The proportions fluctuated year by year, and there were some films that fell in practice into more than one category. In 1938, however, only 10 per cent were classed as political; 41 per cent were categorized as dramas and 49 per cent as comedies. The proportion of political films had declined, in other words, while that of dramas had sharply risen. Musicals, costume dramas, romantic comedies and other genres provided escapism and dulled people's sensibilities; but they could carry a message too. All these films of whatever kind had to conform to the general principles laid down by the Reich Film Chamber, and many of the movies glorified leadership, advertised the peasant virtues of blood and soil, denigrated the Nazi hate-figures such as Bolsheviks and Jews, or depicted them as villains in otherwise apparently unpolitical dramas. Pacifist films were banned, and the Propaganda Ministry ensured that the correct line would be taken in genre movies of all kinds. Thus for example in September i933, the Film-Courier magazine condemned the Weimar cinema's portrayal of "a destructive, subversive criminal class, built up through fantasies of the metropolis into a destructive gigantism" - a clear reference to the films of Fritz Lang, such as Metropolis and M - and assured its readers that in future, films about crime would concentrate not on the criminal "but on the heroes in uniform and in civilian dress who were serving the people in the fight against criminality." Even entertainment, therefore, could be political.

(8) Heinz Linge, With Hitler to the End (1980)

Once Hitler said after Goebbels had left: "A giant in a dwarf's body, a man of size!" The genial, small, simple and not very Aryan-looking man had conquered Red Berlin for Hitler, and Hitler sought his company probably because he cast a ray of light over the greyness of his surroundings. Goebbels's lively and amusing conversation spellbound not only all listeners but also Hitler himself. If Goebbels got the better of a guest at the dinner table with his sharp tongue and irony - this would often be Reich press chief Dr Dietrich - he would always manage to extract humour from the situation. Dietrich, the calm and prudent press man, whose private pleasure was angling, allowed all the fireworks to pass over his head without comment, particularly when Hitler was involved in it. Because of his ostentation, Goring was one of Goebbels' favourite and regular targets. Everything about Goring would have tempted a comedian to make a caricature or impersonation. Goebbels portrayed him as a "Sunday hunter" clad in furs and barricaded into his automobile, he was transported to what he was pleased to call "the wild" and there set up his rifle with telescopic sight in the forked branch of a tree. Hitler, who did not have a high opinion of amateur hunters and preferred the courage of the hunter-trapper, took pleasure in hearing this criticism of his Reich hunt-master.

Although Hitler did not always excel in the selection of his colleagues, in Goebbels he had found a man who filled the office of propaganda minister in masterly fashion. He was "a direct hit", as Hitler once said. When Goebbels addressed thousands, all hung on his words and were equally fascinated and convinced by him as were we who sat around him in a small circle. In addition to these capabilities there was another part of his character which Hitler liked to stress: Goebbels had courage, steadfastness and the will to see things through. At table Goebbels liked to reminisce about the "hall brawls" during the period of struggle, a subject that in times of crisis was seized upon as a "heartener". In Berlin, where the Rhinelander Goebbels felt at his best, he was known as "the little doctor", a term which was in no way derogatory. Everybody knew that like few others before 1933, he had proven his courage and cunning. That these qualities were inherent in his personality I was often able to observe for myself

Goebbels was not frightened to bring to light improprieties resulting from abuses committed by Party members. He reported to Hitler quite candidly on irregularities in the state medical funds, a sector in which SA people had risen to key positions after the seizure of power. When they were unable to justify the trust placed in them, Goebbels stepped in, and after Hitler declined to act Goebbels appealed to the Party court and won. Goebbels cleaned up the pigsties where the old cronies held sway and put a stop to the orgies. That he did not spare his old comrades spoke well for him. Those who were disciplined and considered that their wings had been clipped against the Fuhrer's wishes, staging a protest outside the Propaganda Ministry, ran into an obstacle of granite. Hitler fell in behind Goebbels, who would not allow himself to be intimidated....

Hitler acknowledged the value of Goebbels as a propagandist to his closest circle, where he often would not spare the blushes in being blunt. On the other hand, he did not always approve of Goebbels's private life. The many little stories circulating about Goebbels concerned him deeply. Because radio, the theatre and the film industry all came under the propaganda Ministry, Goebbels often came into contact with actresses and other female artistes upon whom the minister - and perhaps even more so the genial talker who could help one get ahead in one's career - often made a lasting impression. I often noticed how artistes and starlets of film and theatre would swarm around him, rivals for his favour. Goebbels - of whom Hitler secretly wished "if only he had two healthy legs and feet" - had no armour against female wiles, and love affairs were the consequence.

A scandal erupted when the beautiful Czech film star Lida Baarova entered his adoring circle. She exercised such a spell over Goebbels that he quite lost his head and almost wrecked his until then happy marriage with wife Magda. His Secretary of State, Karl Hanke, the personal confidante who knew about Goebbels's affairs, was a person who held Frau Goebbels in the highest regard and was thus at a loss to know which road he should now follow. He came and asked me "to arrange a date to see the Fuhrer", which I did, and now Hitler discovered what lay behind all the rumours. Frau Goebbels wanted a divorce and to emigrate to Switzerland, causing Hitler to envisage for himself a major scandal. He decided to attempt a reconciliation of the couple and invited them both to Obersalzberg. There he received them separately. In individual conversations he explained to them that they must relegate their personal interests to those of the state. The separation was prevented. In the Berghof Great Hall he made them both promise to remain loyal to each other from now on. Happy at having resolved the crisis he brought the reconciled couple himselfto the NSDAP guesthouse on Obersalzberg and wished them jokingly "a happy second honeymoon".

(9) Ernst Hanfstaengel, Hitler: The Missing Years (1957)

The evil genius of the second half of Hitler's career was Goebbels. I always likened this mocking, jealous, vicious, satanically gifted dwarf to the pilot-fish of the Hitler shark. It was he who finally turned Hitler fanatically against all established institutions and forms of authority. He was not only schizophrenic but schizopedic, and that was what made him so sinister.

Even Magda, whom he led a dog's life, was not spared his complexes. He had a private cinema-show in his house one time, and just as he was on his way out, up some highly polished wooden steps, to stand and greet his guests as they left, he slipped on his club foot and all but fell down. Magna managed to save him and pull him up beside her. After a moment to recover and before the whole company, he gripped her by the back of the neck and forced her right down to his knee and said, with that sort of mad laughter, "So, you saved my life that time. That seems to please you a lot." Anyone who did not witness the scene would never believe it, but those who did caught their breath at the depth of character depravity it revealed.

(10) In March 1945 Joseph Goebbels wrote about the decision to kill Ernst Röhm in 1934.

I point out to the Führer at length that in 1934 we unfortunately failed to reform the Wehrmacht when we had an opportunity of doing so. What Roehm wanted was, of course, right in itself but in practice it could not be carried through by a homosexual and an anarchist. Had Roehm been an upright solid personality, in all probability some hundred generals rather than some hundred SA leaders would have been shot on 30 June. The whole course of events was profoundly tragic and today we are feeling its effects. In that year the time was ripe to revolutionise the Reichswehr. As things were the Führer was unable to seize the opportunity. It is questionable whether today we can ever make good what we missed doing at that time. I am very doubtful of it. Nevertheless the attempt must be made.

(11) Traudl Junge, To The Last Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary (2002)

Goebbels brought verve and wit into the conversation. He wasn't at all handsome, but I could see why the girls in the Reich Chancellery ran to the windows to see the Propaganda Minister leave his Ministry, but took hardly any notice of Hitler. "Oh, if you only knew what eyes Goebbels has, and what an enchanting smile!" they gushed, as I looked blankly at them. The ladies at the Berghof positively flirted with Hitler's Minister too. He really did have a delightfully entertaining manner, and his shafts of wit were well aimed, although mostly at other people's expense. No one around the Fuhrer's table could stand up to his sharp tongue, least of all the Reich press chief, who made the slightly improper remark that he got his best ideas in the bathtub, to which Goebbels, of course, promptly replied, "You should take a bath more often, Dr Dietrich!" The press chief went pale and said no more.

So the chatter round the table went on, and Goebbels aimed his sallies, which hit their mark and were not returned. Curiously enough, Himmler and Goebbels entirely ignored each other. It wasn't too obvious, but still you couldn't help noticing that their relationship was a superficial veneer of civility. The two of them met relatively seldom; they didn't have much to do with each other, and were not, like the warring Bormann brothers, kept on the same leash by their master. The hostility between the Bormanns was so habitual and firmly established that they could stand side by side and ignore each other entirely. And when Hitler gave a letter or request to the younger Bormann to be passed on to the Reichsleiter, Albert Bormann would go out, find an orderly, and the orderly would pass instructions on to his big brother even if they were both in the same room. The same thing happened in reverse, and if one Bormann told a funny story at table all the rest of the company would roar with laughter, while his brother just sat there ignoring them and looking deadly serious. I was surprised to find how used Hitler had become to this state of affairs. He took no notice of it at all. Unfortunately I never managed to find out the reason for their enmity. I think there was a woman behind it. Or perhaps those two fighting cocks had long ago forgotten the reason themselves?

(12) Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History (2001)

A Decree on the Exclusion of Jews from German Economic Life (in 1938) banned Jews from all independent business activity, from cornershops to wholesale trade. A Law on the Use of Jewish Assets meant that securities went into closed accounts and that Jews could no longer buy or sell jewels, precious metals or works of art freely.

A bald recitation of these measures does not convey the political dynamics of the discussion, the antisemitic humour, nor the future possibilities which were aired during its interminable course. For these people as often revealed that they thought far ahead, as they appeared to react to unforeseen circumstances. The bluff chairman did most of the talking. Bored by the complexity of the financial and insurance issues arising from the pogrom, Goering ventured the thought that it would have been better had two hundred Jews been killed than that such material damage had been incurred. Actually, that number had been killed, but he appeared not to have noticed. Surveying the measures agreed upon, he commented, "the swine won't commit a second murder so quickly.I must confess, I would not like to he a Jew in Germany," Contemplating the prospect of a war in the near future, he went on, "it is obvious that we in Germany will first of all make sure of settling accounts with the Jews". Goebbels' interventions were both frivolous and malicious. He wanted Jews banned from baths, beaches, cinemas, circuses, theatres and German forests. Goring suggested confining them to certain parts of forests which could then be populated with animals "which look damned similar to Jews - yes, the elk has a curved nose". There was a bizarre digression about whether or not to create segregated compartments for Jews in trains. What if only one Jew wanted to catch a certain train? Should he be given a carriage to himself? Of course not, for laws had their limits: "We will kick him out and he will have to sit all alone in the lavatory all the way."

(13) Conference on the Jewish Question between Hermann Goering, Reinhard Heydrich and Joseph Goebbels (12th November 1938)

Reinhard Heydreich: In almost all German cities synagogues are burned. New, various possibilities exist to utilize the space where the synagogues stood. Some cities want to build parks in their place, others want to put up new buildings.

Hermann Goering: How many synagogues were actually burned?

Reinhard Heydreich: Altogether there are 101 synagogues destroyed by fire, 76 synagogues demolished, and 7,500 stores ruined in the Reich.

Hermann Goering: What do you mean "destroyed by fire"?

Reinhard Heydreich: Partly they are razed, and partly gutted.

Joseph Goebbels: I am of the opinion that this is our chance to dissolve the synagogues. All those not completely intact shall be razed by the Jews. The Jews shall pay for it. There in Berlin, the Jews are ready to do that. The synagogues which burned in Berlin are being leveled by the Jews themselves. We shall build parking lots in their places or new buildings. That ought to be the criterion for the whole country, the Jews shall have to remove the damaged or burned synagogues, and shall have to provide us with ready free space. I deem it necessary to issue a decree forbidding the Jews to enter German theaters, movie houses and circuses. I have already issued such a decree under the authority of the law of the chamber for culture. Considering the present situation of the theaters, I believe we can afford that. Our theaters are overcrowded, we have hardly any room. I am of the opinion that it is not possible to have Jews sitting next to Germans in varieties, movies and theaters. One might consider, later on, to let the Jews have one or two movie houses here in Berlin, where they may see Jewish movies. But in German theaters they have no business anymore. Furthermore, I advocate that the Jews be eliminated from all positions in public life in which they may prove to be provocative. It is still possible today that a Jew shares a compartment in a sleeping car with a German. Therefore, we need a decree by the Reich Ministry for Communications stating that separate compartments for Jews shall be available; in cases where compartments are filled up, Jews cannot claim a seat. They shall be given a separate compartment only after all Germans have secured seats. They shall not mix with Germans, and if there is no more room, they shall have to stand in the corridor.

Hermann Goering: In that case, I think it would make more sense to give them separate compartments.

Joseph Goebbels: Not if the train is overcrowded!

Hermann Goering: Just a moment. There'll be only one Jewish coach. If that is filled up, the other Jews will have to stay at home.

Joseph Goebbels: Furthermore, there ought to be a decree barring Jews from German beaches and resorts. Last summer.

Hermann Goering: Particularly here in the Admiralspalast very disgusting things have happened lately.

Joseph Goebbels: Also at the Wannsee beach. A law which definitely forbids the Jews to visit German resorts.

Hermann Goering: We could give them their own.

Joseph Goebbels: It would have to be considered whether we'd give them their own or whether we should turn a few German resorts over to them, but not the finest and the best, so we cannot say the Jews go there for recreation. It'll also have to be considered if it might not become necessary to forbid the Jews to enter the German forest. In the Grunewald, whole herds of them are running around. It is a constant provocation and we are having incidents all the time. The behavior of the Jews is so inciting and provocative that brawls are a daily routine.

Hermann Goering: We shall give the Jews a certain part of the forest, and the Alpers shall take care of it that various animals that look damned much like Jews -the elk has such a crooked nose - get there also and become acclimated.

(14) In his diary Joseph Goebbels recorded how he expected a quick victory in the Soviet Union (July 1941)

The Führer thinks that the action will take only 4 months; I think - even less. Bolshevism will collapse as a house of cards. We are facing an unprecedented victorious campaign.

Cooperation with Russia was in fact a stain on our reputation. Now it is going to be washed out. The very thing we were struggling against for our whole lives, will now be destroyed. I tell this to the Führer and he agrees with me completely.

(15) In his diary Joseph Goebbels recorded how Adolf Hitler had decided to increase the terror bombing attacks on Britain (25th April, 1942)

He said he would repeat these raids night after night until the English were sick and tired of terror attacks. He shares my opinion absolutely that cultural centres, health resorts and civilian resorts must be attacked now. There is no other way of bringing the English to their senses. They belong to a class of human beings with whom you can only talk after you have first knocked out their teeth.

(16) Laurence Rees, The Nazis: A Warning from History (2005)

Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda Minister and Gauleiter of Berlin, was one of those who took the lead that summer (1941) in pushing for the Jews of Berlin to be forcibly deported East. At a meeting on 15 August Goebbels' state secretary, Leopold Gutterer, pointed out that of the 70,000 Jews in Berlin only 19,000 were working (a situation, of course, that the Nazis had created themselves by enforcing a series of restrictive regulations against German Jews). The rest, argued Gutterer, ought to be "carted off to Russia... best of all actually would be to kill them." And when Goebbels himself met Hitler on 19 August he made a similar case for the swift deportation of the Berlin Jews.

Dominant in Goebbels' mind was the Nazi fantasy of the role that German Jews had played during World War I. While German soldiers had suffered at the front line, the Jews had supposedly been profiting from the bloodshed back in the safety of the big cities (in reality, of course, German Jews had been dying at the front in proportionately the same numbers as their fellow countrymen). But now, in the summer of 1941, it was obvious that Jews remained in Berlin while the Wehrmacht were engaged in their brutal struggle in the East - what else could they do, since the Nazis had forbidden German Jews to join the armed forces? As they did so often, the Nazis had created for themselves the exact circumstances that best fitted their prejudice. But despite Goebbels' entreaties, Hitler was still not willing to allow the Berlin Jews to be deported. He maintained that the war was still the priority and the Jewish question would have to wait. However, Hitler did grant one of Goebbels' requests. In a significant escalation of Nazi anti-Semitic measures, he agreed that the Jews of Germany should be marked with the yellow star. In the ghettos of Poland the Jews had been marked in similar ways from the first months of the war, but their counterparts in Germany had up to now escaped such humiliation.

(17) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (27th March, 1942)

The Jews are now being forced eastwards from the General Government, commencing with Lublin. A pretty barbaric method, not to be described in detail, is being used here, and not much of the Jews themselves remains afterwards.... The former Gauleiter of Vienna (Globocnik) is in charge of this operation, and is doing it with considerable circumspection and with methods which do not attract much attention. A judicial sentence is being carried out against the Jews which is certainly barbaric, but which they have fully deserved. What the Fuhrer prophesied in the eventuality of the Jews bringing about a new world war has begun to be realised in the most terrible fashion. In these matters, one cannot let sentimentality prevail. If we did not defend ourselves against them, the Jews would exterminate us. It is a life and death struggle between the Aryan race and the Jewish bacillus. No other government and no other regime could muster the strength for a general solution of this question. Here too, the Fuhrer is the untiring advocate and champion of a radical solution, which the situation demands, and which therefore appears inevitable. Thank God the war affords us a series of opportunities which were denied us in peacetime. We must make use of them. The ghettos in the towns of the General Government which have been made vacant can now be filled with the Jews expelled from the Reich, and then the process can be repeated after a certain time.

(18) Joseph Goebbels, diary (7th March, 1945)