Erich Mühsam

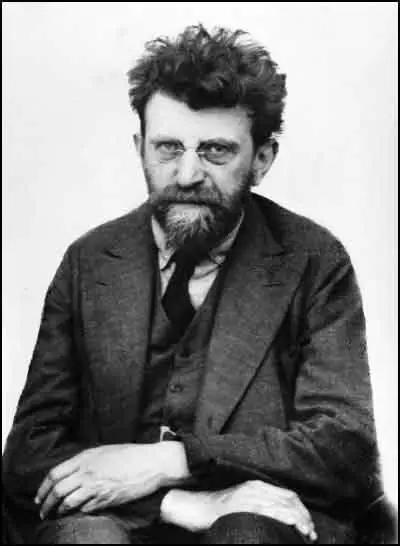

Erich Mühsam, the son of Siegfried Mühsam, a pharmacist, and Rosalie Seligmann, was born in Berlin on 6th April, 1878. His parents were orthodox Jews. Erich had three siblings Elisabeth Margarethe (1875), Hans Günther (1876) and Charlotte (1881). When Erich was one year old, the family moved to Lubeck, where the children were educated at local schools. (1)

As a young man he had a strong desire to become a poet: " I was completely defined by my poetry, and if my poetry was all that I had to offer to the people, then I could write an autobiography that satisfies the simple needs of literary historians for classification... Early attempts at poetry with no support from school or parents. Poetry was seen as a distraction from duty and had to be pursued in secrecy." (2)

Mühsam was expelled from school at the age of sixteen for "socialist agitation". According to the headmaster, Mühsam had leaked a speech of his to a socialist newspaper, Lübecker Volksboten (Messenger for the People): "As a consequence, the journal published a scandalous and disgraceful article about our school and a reprint of my speech, shortened, distorted, ridiculed, and with sardonic commentary - in truth, both the content and the form of the speech were noble, warm, and well measured. With this deceitful betrayal, Mühsam has placed himself beyond the school's boundaries and severed all ties with it." (3)

Following his father's wishes, Mühsam became a pharmacist apprentice. Soon after the death of his mother, he moved to Berlin. He associated with other left-wing thinkers. This included the social reformer, Heinrich Hart, who encouraged him to follow his true passion, writing, even if it brought him into conflict with his father. According to another friend, Hart argued: "If you are not afraid of a little hunger and some missteps, then go ahead and do what you have to do! How can one discourage a man from doing what he wants to?" (4)

Mühsam later argued: "Even at a young age, I realized that the state apparatus determined the injustice of all social institutions. To fight the state and the forms in which it expresses itself - capitalism, imperialism, militarism, class domination, political judiciary, and oppression of any kind - has always been the motivation for my actions. I was an anarchist before I knew what anarchism was. I became a socialist and communist when I began to understand the origins of injustice in the social fabric." (5)

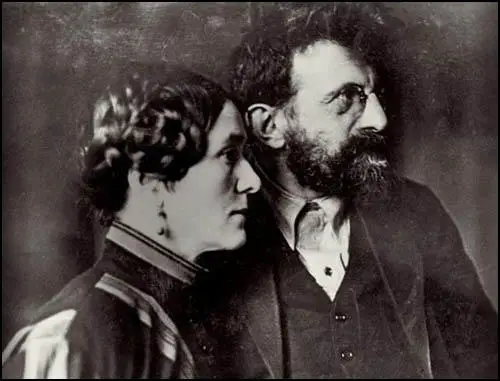

Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer

Mühsam was deeply influenced by the ideas of Gustav Landauer, a leading anarchist. "Landauer was an anarchist all his life. However, it would be utterly ridiculous to read his various ideas through the glasses of a specific anarchist branch, to praise or condemn him as an individualist, communist, collectivist, terrorist, or pacifist... Landauer, never saw anarchism as a politically or organizationally limited doctrine, but as an expression of ordered freedom in thought and action." (6)

It has been argued that in the beginning, Mühsam, the younger and politically less experienced of the two, looked up to Landauer; a teacher-student dynamic long characterized their relationship. "However, Mühsam was clearly independent in his ideas and soon equaled Landauer in influence. Among the most notable differences between the two was Mühsam's openness to party communism, never shared by Landauer. There were also disparities in character: Landauer often appeared to be the philosopher and sage, while Mühsam was notoriously restless and temperamental... While Mühsam immersed himself passionately in debates about free love or the rights of homosexuals, Landauer remained cautious in these respects and always held on to marriage and family as important miniature examples of the communities on which to build a socialist society." (7)

Another friend during this period was Rudolf Rocker. He later commented on Mühsam's personality: "There was something child-like and unconstrained, something joyful in this man; something that no personal sorrow, no misery could erase. With an almost lyrical passion, he believed in the proletariat... natural desire for freedom, and whenever I challenged this assumption, it deeply upset him.... Mühsam was a believer. His belief could move mountains. He was a poet to whom there was no clear difference between the reality of life and his dreams." (8)

Augustin Souchy was another anarchist who appreciated Mühsam's talents: "He had a fascinating personality; he was spiritual, imaginative, witty, funny, and possessed a great sense of irony - at the same time he was kind, helpful, and emphatic... Erich had his heart in his hand, and comradeship in his blood." Mühsam also became friends with Frank Wedekind. One one occasion he said to Mühsam: "You always ride on two horses that pull in different directions. One day, they will tear your legs off!" Mühsam replied: "If I let go of one, I will lose my balance and break my neck." (9)

Sozialistischer Bund

In 1908 Mühsam and Gustav Landauer established Sozialistischer Bund in May 1908, with the stated goal of "uniting all humans who are serious about realizing socialism". Landauer and Mühsam hoped to inspire the creation of small independent cooperatives and communes as the basic cells of a new socialist society. To support the new organisation, Landauer revived Der Sozialist, describing it as the Journal of the Socialist Bund. (10)

Chris Hirte has argued that the made a good combination: "To sit in a chamber and to dream of anarchist settlements, as Landauer did, was not Mühsam's way. He had to be in the midst of life; he had to be where life was at its most colorful, where things fermented and brewed." Other important members included Martin Buber and Margarethe Faas-Hardegger. At its height, they had around 800 people associated with the group. Landauer argued: "The difference between us socialists in the Socialist Bund and the communists is not that we have a different model of a future society. The difference is that we do not have any model. we embrace the future's openness and refuse to determine it. What we want is to realize socialism, doing what we can for its realization now." (11)

According to Gabriel Kuhn: "There were a few points of contention. The most important concerned matters of family life and sexuality. Laudauer, who saw the nuclear family as the social core of mutual aid and solidarity, repeatedly drew the ire of Mühsam, who was a strong believer in free love and sexual experimentation. The conflict came to a head in 1910 over the publication of Landauer's article Tarnowska, a biting critique of free love, which Landauer saw as a mere pretext for moral and social degeneration. For a while, Mühsam even saw the friendship threatened, but the two soon managed to work out their differences." (12)

Gustav Landauer also damaged his relationship with Margarethe Faas-Hardegger when he criticized her for an article questioning the nuclear family and arguing for communal child rearing. He admitted to Mühsam that "it has always been difficult for me to adopt and execute the ideas and plans for others". Mühsam pointed out: "Only those who see him as a determined and fearless fighter, kind, soft, and generous in everyday relations, but intolerant, hard, and head-strong to the point of arrogance in important issues, can understand him the way he really was." (13)

In April 1911 Mühsam established the monthly magazine Kain-Zeitschrift für Menschlichkeit (Cain - Journal for Humanity). Virtually a one man operation, the socialist journal sold well enough to guarantee Mühsam a modest living. In its first edition Mühsam wrote: "This journal has been founded without capital. Not because of any principle, but because there was no capital." (14) In his autobiography he pointed out that he was not just a journalist: "I did tedious political work like distributing leaflets and going door-to-door, and that I gave lectures at group meetings and speeches at large gatherings." (15)

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War Mühsam controversially commented: "I am united with all Germans in the wish that we can keep foreign hordes away from our women and children, away from our towns and fields." He later apologized to his friends and admitted that he had written the words "under the pressure of anxiety, fear, mental strain, and emotional turmoil." (16) It was not long before Mühsam withdrew this statement and joined Gustav Landauer in anti-war activities. (17)

Mühsam led a very promiscuous life but he eventually became very close to Zenzl Elfinger, the daughter of an innkeeper. He wrote in his diary in December, 1914: "This morning, when she sat at my bed, I realized how dear she is to me. She comes close to what I most long for in a lover: a substitute for my mother. I can put my head in her lap and let her caress me quietly for hours. I don't feel the same with anyone else. Her love is extremely important to me, and I have to thank her more in these hard times than I sometimes realize myself. Maybe I can return some of this one day!" (18)

In July 1915, Siegfried Mühsam died. They had a very poor relationship ever since Erich Mühsam abandoned his career as a pharmacist for the life of a writer, bohemian, and political activist, but he still believed he would inherit enough money to fell financially secure. This did not happen and he wrote in his diary: "Now the whole misery starts anew - the only difference being that I will no longer be able to borrow money in the name of an impending inheritance." (19)

In September, 1915, Erich Mühsam married Zenzl Elfinger. Despite his ongoing promiscuity and related problems, she remained his lifelong companion. As a result of his anti-war activities, Mühsam was banished from Munich on 24th April 1918, to a small Bavarian town of Traunstein. On 28th October, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany. (20)

The German Revolution

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a Council Republic. Eisner's program was democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. Mühsam immediately returned to Munich to take part in the revolution. Other socialists who returned to the city included Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution. (21)

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds." (22)

In Bavaia, Kurt Eisner formed a coalition with the German Social Democrat Party (SDP) in the National Assembly. The Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) only received 2.5% of the total vote and he decided to resign to allow the SDP to form a stable government. He was on his way to present his resignation to the Bavarian parliament on 21st February, 1919, when he was assassinated in Munich by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. (23)

It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." Johannes Hoffmann, of the SDP, replaced Eisner as President of Bavaria. One armed worker walked into the assembled parliament and shot dead one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Party. Many of the deputies fled in terror from the city. (24)

Max Levien, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), became the new leader of the revolution. Rosa Levine-Meyer argued: "Levien.... was a man of great intelligence and erudition and an excellent speaker. He exercised an enormous appeal of the masses and could, with no great exaggeration, be defined as the revolutionary idol of Munich. But he owed his popularity rather to his brilliance and wit than to clear-mindedness and revolutionary expediency." (25)

On 7th April, 1919, Levien declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. A fellow revolutionary, Paul Frölich later commented: "The Soviet Republic did not arise from the immediate needs of the working class... The establishment of a Soviet Republic was to the Independents and anarchists a reshuffling of political offices... For this handful of people the Soviet Republic was established when their bargaining at the green table had been closed... The masses outside were to them little more than believers about to receive the gift of salvation from the hands of these little gods. The thought that the Soviet Republic could only arise out of the mass movement was far removed from them. While they achieved the Soviet Republic they lacked the most important component, the councils." (26)

Ernst Toller, a member of the Independent Socialist Party, became a growing influence in the revolutionary council. Rosa Levine-Meyer claimed that: "Toller was too intoxicated with the prospect of playing the Bavarian Lenin to miss the occasion. To prove himself worthy of his prospective allies, he borrowed a few of their slogans and presented them to the Social Democrats as conditions for his collaboration. They included such impressive demands as: Dictatorship of the class-conscious proletariat; socialization of industry, banks and large estates; reorganization of the bureaucratic state and local government machine and administrative control by Workers' and Peasants' Councils; introduction of compulsory labour for the bourgeoisie; establishment of a Red Army, etc. - twelve conditions in all." (27)

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982) has pointed out: "Meanwhile, conditions for the mass of the population were getting worse daily. There were now some 40,000 unemployed in the city. A bitterly cold March had depleted coal stocks and caused a cancellation of all fuel rations. The city municipality was bankrupt, with its own employees refusing to accept its paper currency." (28)

Eugen Levine, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), arrived in Munich from Berlin. The leadership of the KPD was determined to avoid any repetition of the events in Berlin in January, when its leaders, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, were murdered by the authorities. Levine was instructed that "any occasion for military action by government troops must be strictly avoided". Levine immediately set about reorganizing the party to separate it off clearly from the anarcho-communists led by Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer. He reported back to Berlin that he had about 3,000 members of the KPD under his control. In a letter to his wife he commented that "in a few days the adventure will be liquidated". (29)

Levine pointed out that despite the Max Levien declaration, little had changed in the city: "The third day of the Soviet Republic... In the factories the workers toil and drudge as ever before for the capitalists. In the offices sit the same royal functionaries. In the streets the old armed guardians of the capitalist world keep order. The scissors of the war profiteers and the dividend hunters still snip away. The rotary presses of the capitalist press still rattle on, spewing out poison and gall, lies and calumnies to the people craving for revolutionary enlightenment... Not a single bourgeois has been disarmed, not a single worker has been armed." Levine now gave orders for over 10,000 rifles to be distributed. (30)

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly." (31)

Erich Mühsam was arrested and sentenced to fifteen years of confinement in a fortress. A few weeks later, the Weimar Republic was established, giving Germany a parliamentarian constitution. Gabriel Kuhn has argued: "Being confined in a fortress - a sentence usually reserved for political dissidents - meant certain privileges compared to the general prison population, most notably the opening of cells for communal meetings and activities during the day, but it also meant increased harassment, reaching from the confiscation of papers and diaries to punishments like isolation and food deprivation. Mühsam's health deteriorated drastically during those years." (32)

While in prison Mühsam briefly joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He explained in a letter to a friend, Martin Andersen Nexø: "I recently joined the Communist Party - of course not to follow the party line, but to be able to work against it from the inside." (33) He also praised Lenin and the Bolsheviks but left the KPD when he heard about how the anarchists were being treated in Russia. (34)

Mühsam was released from prison on 20th December, 1924. He was greeted by a large gathering of sympathizers when he arrived in Berlin. The scene was later described by the journalist, Bruno Frei: "Thanks to my press card I was able to get past the police barriers. Helmet-wearing security forces, both on foot and on horses, had sealed off the station. On the square in front of it, there were several hundred, maybe a thousand workers and youths with flags and banners. Their republican deed: to greet Erich Mühsam! When the express train from Munich arrived, a few youngsters managed to make their way into the arrival hall. Mühsam stepped out of the train in obvious pain, accompanied by his wife Zenzl. The young workers lifted him on their shoulders.... Mühsam fought back tears and thanked the comrades. Someone started to sing The Internationale. At that very moment, the helmet-wearing mob attacked the people who had gathered around Mühsam. They yelled at them, pushed them, and hit them with batons. The comrades resisted courageously, though, protected Mühsam, and led him outside. Unfortunately, the police had already begun to chase the workers from the square.... Many were arrested and wounded." (35)

Mühsam established the United Front of the Revolutionary Proletariat but it eventually collapsed for lack of support. He also worked with the Federation of Communist Anarchists of Germany (FKAD) but in 1925 he was expelled for carrying out "open propaganda in the interests the Communist Party" that was "not compatible with fundamental anarchist principles". Mühsam retaliated by saying that he was "an anarchist without always agreeing with the ideology and tactics of the majority of German anarchists." (36)

In October 1926 he started the journal Fanal. He argued that there was the need for a revolutionary journal that dealt with the political significance of theatre and of the arts in general. The first edition was completely written by Mühsam: "There will be no contributions from others. I was in Bavarian captivity for almost six years and practically prohibited from presenting my thoughts to a wider public... People ought to grant me the modest sixteen pages I intend to fill every month, so that finally I can propagate ideas that no one else will print." (37)

Mühsam promoted the work of left-wing artists and writers such as Bertolt Brecht, Ernst Toller, George Grosz, John Heartfield and Erwin Piscator: "Agitational art is good and necessary. It is needed by the proletariat both in revolutionary times and in the present. But it has to be art, skilled, spirited, and glittering. All arts have agitational potential, but none more than drama, In the theatre, living people present living passion. Here, more than anywhere else, true art can communicate true conviction. Here, the idea of a revolutionary worker can be materialized.... Arts must inspire people, and inspiration comes from the spirit. It is not our task to teach the minds of the workers with the help of the arts - it is our task to bring spirit to the minds of the workers with the help of the arts, as the spirit of the arts knows no limits. Neither dialectics nor historical materialism have anything to do with this; the only art that can enthuse and enflame the proletariat is the one that derives its richness and its fire from the spirit of freedom." (38)

Mühsam was an effective public speaker. Fritz Erpenbeck has argued: "He (Mühsam) was able to capture the masses. He spoke with real passion and appealed to the people's feelings... He described events with such involvement that it felt real people believed him." Rudolf Rocker wrote: "As a human being, Mühsam was one of the most beautiful people I have ever met. He belonged to no party, which means that the humanity in him had not been destroyed, as in so many others. He was always noble in his conduct, a loyal and dedicated friend, and an enormously thoughtful and entertaining host." (39)

Nazi Germany

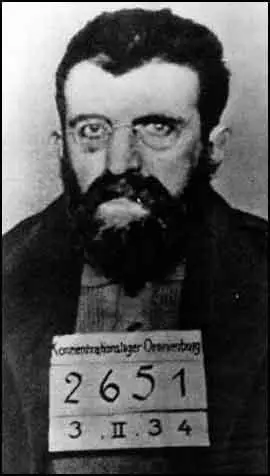

After Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933, Mühsam campaigned against the Nazi Party. He was arrested on 28th February, 1934 and was sent to a concentration camp in Oranienburg. His friend, Alexander Berkman, published details of his predicament: "I received a note from Germany yesterday. Erich Mühsam, the idealist, revolutionary, and Jew, represents everything that Hitler and his followers hate. They are attempting to destroy cultural and progressive life in Germany by destroying him. Mühsam became a particular object of Hitler's scorn because of his outstanding role in the Munich Revolution, alongside men like Landauer, Levine, and Toller." (40)

A fellow prisoner later recalled how Mühsam was regularly beaten: "Erich staggered, tripped over a bank, and fell on some straw mattresses. The wardens jumped after him, striking more blows. We stood still, clenching our fists and grinding our teeth, condemned to watch. We knew from experience that the slightest sign of resistance would send us to the hole for fourteen days or straight to the medical ward. Finally, the wardens pulled Erich up again and taunted him... They hit Erich again with their fists. He fell back onto the straw mattresses, the wardens followed and continued to hit and kick him." (41)

Another prisoner, John Stone, described how Erich Mühsam was murdered on 10th July, 1934: "In the evening, Mühsam was ordered to see the camp's commanders. When he returned, he said, They want me to hang myself - but I will not do them the favor. We went to bed at 8 p.m., as usual. At 9 p.m., they called Mühsam from his cell. This was the last time we saw him alive. It was clear that something out of the ordinary was happening. We were not allowed to go to the latrines in the yard that night. The next morning, we understood why: we found Mühsam's battered corpse there, dangling from a rope tied to a wooden bar. Obviously, the scene was supposed to look like a suicide. But it wasn't. If a man hangs himself, his legs are stretched because of the weight, and his tongue sticks out of his mouth. Mühsam's body didn't show any of these signs. His legs were bent. Furthermore, the rope was attached to the bar by an advanced bowline knot. Mühsam knew nothing about these things and would have been unable to tie it. Finally, the body showed clear indications of recent abuse. Mühsam had been beaten to death before he was hanged." (42)

Zenzl Mühsam confirmed the death of her husband to his friend, Rudolf Rocker: "I have to talk to you. On July 16, my Erich was buried at Waldfriedhof Dahlem. I was not allowed to go to the funeral, because my relatives were afraid. I was the only living witness, apart from his comrades in prison, who saw him being tortured. I have seen Erich dead, my dear. He looked so beautiful. There was no fear on his face; his cold hands were so gorgeous when I kissed them goodbye. Every day it becomes clearer to me that I will never talk to Erich again. Never. I wonder if anyone in this world can comprehend this? I am in Prague with friends now. I have not found real peace yet, although I am tired, very tired. Money is a problem. For now, I must remain here. The authorities, the police etc. are very good to me." (43)

Primary Sources

(1) Erich Mühsam, Autobiography (1927)

It is not the external facts that determine a persons life; it is the internal changes that a person goes through. They define the impact of a person on his or her surroundings. The events in the life of an individual are only of interest in the context of life's events in general. Individuals whose personal lives have never had any relevance for social life might be very interesting to study for those interested in the human soul, but they are of no relevance for the community.

If I was completely defined by my poetry, and if my poetry was all that I had to offer to the people, then I could write an autobiography that satisfies the simple needs of literary historians for classification.

Born on April 6, 1878, in Berlin. Childhood, youth, high school in Lubeck. Teachers who did not understand this particular child, and who did not see his special traits. No one else did either. Rebellion, laziness, and the occupation with "strange" things as a logical outcome. Early attempts at poetry with no support from school or parents. Poetry was seen as a distraction from duty and had to be pursued in secrecy. Involved in many pranks, and, as a high school freshman, passed on a report about internal school affairs to the social democratic paper, with the consequence of being expelled for "socialist activities."

One year as a high school sophomore in Parchim, Mecklenburg, then back to Lubeck as an apprentice in a pharmacy. Worked in different pharmacies and moved to Berlin in 1900. Joined the Hart brothers' Neue Gemeinschaft as an independent writer. Acquaintance with many public figures and friendships with Gustav Landauer, Peter Hille, Paul Scheerbart, and others. Bohemian life. Travels to Switzerland, Italy, Austria, France. Finally, settled in Munich in 1909. Cabaret and work as a theater criric. A lot of writing, mostly polemical essays. Friendly interaction with Frank Wedekind and many other poets and artists. Publication of three volumes of poetry and of four plays. From 1911 to 1914, editor of the literary and revolutionary monthly Kain-Zeitsdbrirt fur Mensdblidbkeit, published as a journal focusing on the German Revolution frorn November 1918 to April 1919. Since then, I have been in the hands of the counterrevolutionary Bavarian state.

Again, if my life was defined by my literary achievements alone, then this information would suffice. However, I see my work as a writer, especially my poetry, only as an archive of my soul, only as a partial expression of who I am. A human being's personality is the result of all the outside impressions gathered by mind and heart. My personality is a revolutionary one. In my personal development and in my activities I have always resisted everything that was imposed on me, both in private and in social life. I have done so since my early childhood.

Even at a young age, I realized that the state apparatus determined the injustice of all social institutions. To fight the state and the forms in which it expresses itself - capitalism, imperialism, militarism, class domination, political judiciary, and oppression of any kind - has always been the motivation for my actions. I was an anarchist before I knew what anarchism was. I became a socialist and communist when I began to understand the origins of injustice in the social fabric. I owe the clarification of my views to Gustav Landauer: he was my teacher until the white guards, called in by the social democratic government to crush the Bavarian Revolution, murdered him.

My revolutionary activity has often brought me in conflict with the state. In 1910, I stood in front of a judge because I had attempted to raise socialist consciousness among the so-called lumpenproletariat. During the war, I actively opposed those who were determining Germany's fate. I was detained in Traunstein because I refused to serve the fatherland as a medical orderly. I stayed there until the "Great Time" ended in defeat and collapse.

The revolution found me at my post from the first hour. I was a member of the Revolutionary Workers' Council. I fought against Eisner's politics of concession. I participated in the proclamation of the Bavarian Council Republic. I was sentenced to fifteen years of confinement in a fortress by a drumhead court-martial.

(2) Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho-Syndicalism (1947)

There was something child-like and unconstrained, something joyful in this man; something that no personal sorrow, no misery could erase. With an almost lyrical passion, he believed in the proletariat... natural desire for freedom, and whenever I challenged this assumption, it deeply upset him. His soul was filled by the same convictions that had once filled the souls of Russia's youth-those who "went to the people," following Bakunin's call. Muhsam was a believer. His belief could move mountains. He was a poet to whom there was no clear difference between the reality of life and his dreams....

As a human being, Mühsam was one of the most beautiful people I have ever met. He belonged to no party, which means that the humanity in him had not been destroyed, as in so many others. He was always noble in his conduct, a loyal and dedicated friend, and an enormously thoughtful and entertaining host."

(3) Bruno Frei, Mühsam's Arrival in Berlin (December, 1924)

Thanks to my press card I was able to get past the police barriers. Helmet-wearing security forces, both on foot and on horses, had sealed off the station. On the square in front of it, there were several hundred, maybe a thousand workers and youths with flags and banners. Their republican deed: to greet Erich Mühsam! When the express train from Munich arrived, a few youngsters managed to make their way into the arrival hall. Mühsam stepped out of the train in obvious pain, accompanied by his wife Zenzl. The young workers lifted him on their shoulders.... Mühsam fought back tears and thanked the comrades. Someone started to sing The Internationale. At that very moment, the helmet-wearing mob attacked the people who had gathered around Muhsam. They yelled at them, pushed them, and hit them with batons. The comrades resisted courageously, though, protected Miihsam, and led him outside. Unfortunately, the police had already begun to chase the workers from the square.... Many were arrested and wounded.

(4) Federation of Communist Anarchists of Germany, statement (1925)

We ask our comrades to no longer provide Erich Muhsam with the platforms that he uses to hurt our movement It does not matter whether or not Muhsam still calls himself an anarchist We are taking this opportunity to clearly state that Miihsam's activity for "non-party" organizations under the thumb of the KPD is non-anarchistic, and that we no longer see him as an anarchist.

(5) Erich Mühsam, Fanal (October, 1926)

There will be no contributions from others. I was in Bavarian captivity for almost six years and practically prohibited from presenting my thoughts to a wider public... People ought to grant me the modest sixteen pages I intend to fill every month, so that finally I can propagate ideas that no one else will print.

(6) Erich Mühsam, Fanal (May, 1930)

Agitational art is good and necessary. It is needed by the proletariat both in revolutionary times and in the present. But it has to be art, skilled, spirited, and glittering. All arts have agitational potential, but none more than drama, In the theatre, living people present living passion. Here, more than anywhere else, true art can communicate true conviction. Here, the idea of a revolutionary worker can be materialized.... Arts must inspire people, and inspiration comes from the spirit. It is not our task to teach the minds of the workers with the help of the arts - it is our task to bring spirit to the minds of the workers with the help of the arts, as the spirit of the arts knows no limits. Neither dialectics nor historical materialism have anything to do with this; the only art that can enthuse and enflame the proletariat is the one that derives its richness and its fire from the spirit of freedom.

(7) Statement made by an unnamed prisoner on 8th August, 1934.

One evening the iron gate to our ward was opened. Achtung!" Everyone jumped up. Two wardens appeared. "Mühsam, step up!" One of the wardens, a big fellow with broad shoulders, held an issue of Arbeiterturri (The Workers) in his hands. "Mühsam, here is an article about you." Then he turned to us: "You have an important figure among you!" Back to Mühsam: "Mühsam, where were you in Munich in 1919? Weren't you some kind of minister?" Erich Mühsam calmly looked at the warden and said, "In 1919, I was on the Executive Council of the Bavarian Council Republic. The warden: "And what did you do?" Mühsam: "We tried to realize the proletarian revolution." "Bullshit" ' yelled the warden and hit Erich in the face. The other warden added a blow. "You pig, you ordered twenty-two hostages to be shot!" Erich staggered, tripped over a bank, and fell on some straw mattresses. The wardens jumped after him, striking more blows. We stood still, clenching our fists and grinding our teeth, condemned to watch. We knew from experience that the slightest sign of resistance would send us to the hole for fourteen days or straight to the medical ward. Finally, the wardens pulled Erich up again and taunted him: "Hey, don't give in right away!" Then the big warden yelled, "So, what did you do in Munich?" One of Erich's eyes was bloodshot. His voice was trembling. He said, "When the twenty-two hostages were shot in Munich, the social democratic government had already put me in prison." The warden raised his hand: "What are you saying, you pig? They put you in prison? You put yourself in prison, because you were afraid and you knew that you were safe from bullets there. You masterminded the revolution, you Jewish pig!" They hit Erich again with their fists. He fell back onto the straw mattresses, the wardens followed and continued to hit and kick him.

(8) Zenzl Mühsam, letter to Rudolf Rocker (31st July, 1934)

I have to talk to you. On July 16, my Erich was buried at Waldfriedhof Dahlem. I was not allowed to go to the funeral, because my relatives were afraid. I was the only living witness, apart from his comrades in prison, who saw him being tortured.

I have seen Erich dead, my dear. He looked so beautiful. There was no fear on his face; his cold hands were so gorgeous when I kissed them goodbye. Every day it becomes clearer to me that I will never talk to Erich again. Never. I wonder if anyone in this world can comprehend this?

I am in Prague with friends now. I have not found real peace yet, although I am tired, very tired. Money is a problem. For now, I must remain here. The authorities, the police etc. are very good to me.