John Heartfield

Helmut Herzfeld was born in Berlin, Germany on 19th June, 1891. His father, Franz Held, was a socialist writer and his mother, Alice Stolzenberg, was a textile worker and a trade union activist. As a result of their politics the family was forced to flee to Switzerland in 1896. (1)

After leaving school at fourteen Herzfeld worked for a bookseller, Heinrich Heuss, in Wiesbaden. In 1907 he became an assistant to the painter, Hermann Bouffier, and two years later became a student at the School of Applied Arts in Munich. In 1912 Herzfeld started work as a designer in Mannheim for a year before moving to Berlin to study under Ernst Neumann at the Arts and Crafts School. (2)

Helmut Herzfeld was drafted into the German Army in 1915 but succeeds in evading military service. (3) Karl Liebknecht, the leader of the Spartacus League, a secret organization, published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity." (4)

On 1st May, 1916, the Spartacus League decided to come out into the open and organized a demonstration against the First World War in Berlin. Helmut Herzfeld was in the crowd that day and heard Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg call for everyone to resist Germany's involvement in the war. Several of its leaders, including Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested and imprisoned. Wieland Herzfelde, said that the speeches at the rally had a great influence on his brother. It was at this point he decided to dedicate his art to politics. Wieland later wrote: "We are the soldiers of peace. No nation and no race is our enemy." (5) A pacifist and Marxist, Herzfeld, changed his name to John Heartfield in 1916 in "protest against German nationalistic fervour". (6)

John Heartfield and Photomontage

Heartfield began contributing work to Die Neue Jugend, an arts journal published by his brother. His friend, George Grosz, who worked with him at the journal, later recalled how John Heartfield "developed a new very amusing style of using collage and bold typography". (7) Grosz helped him develop what became known as photomontage (the production of pictures by rearranging selected details of photographs to form a new and convincing unity). We... invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o'clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it." (8)

In 1918 Heartfield and Grosz joined the newly formed German Communist Party (KPD) and over the next fifteen years produced designs and posters for the organization. (9) He participated in the First International Dada Fair of 1920. It is claimed that Heartfield had a major influence on the German Dada group that included Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Raoul Hausmann and Kurt Schwitters. (10)

Sergei Tretyakov was another artist linked to the Dada group. "Heartfield's first Dadaist photomontages are still marked by their abstract nature. Scraps of photograph and printed text are arranged not so much according to meaning but according to the aesthetic mood of the artist. The Dadaist period in Heartfield's work did not continue for long. He soon ceased to waste his artistic talents in abstract fireworks. His works became aimed shots... Soon no line could be drawn between his montages and his party work." (11)

Political Activist

Over the next few years Heartfield produced posters for the KPD. However, to earn a living he worked briefly as a set designer for Max Reinhardt and more consistently for the revolutionary theatre of Erwin Piscator. He also designed book jackets for the left-wing publishers, Malik Verlag. In 1923 Heartfield became editor of the satirical magazine, Der Knöppel. (12)

Bertolt Brecht first met Heartfield in 1924. He pointed out that he soon became one of the most important European artists. "He works in a field that he created himself, the field of photomontage. Through this new form of art he exercises social criticism. Steadfastly on the side of the working class, he unmasked the forces of the Weimar Republic driving toward war." (13) Heartfield wrote: "Art and agitation are mutually exclusive". (14)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

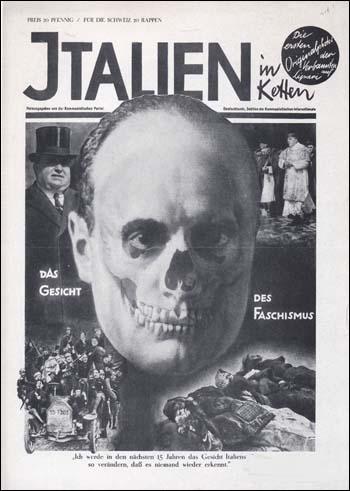

Wieland Herzfelde argued "he consciously placed photography in the service of political agitation". (15) In 1928 he created The Face of Fascism, a montage that dealt with the rule of Benito Mussolini which spread all over Europe with tremendous force. "A skull-like face of Mussolini is eloquently surrounded by his corrupt backers and his dead victims". (16)

Heiri Strub has pointed out that Heartfield made the decision to use his art for political causes. "Heartfield always considered his photomontages as artistic achievements. He took in stride the fact that he was not recognized by contemporary art critics. The works he created for dissemination in huge editions had no value in the art market. Directing his political charges at the masses, he could scarcely count on a sympathetic reaction from bourgeois art collectors. The worker, however, for whom he intended his photomontages, understood their revolutionary content, but assigned no artistic value judgment to them." (17)

John Heartfield and AIG Magazine

Heartfield began working for the socialist magazine, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIG) in 1929. During this period it became the most widely socialist pictorial newspaper in Germany. Circulation reached 350,000 in 1930. (18) Zbyněk Zeman has pointed out that at this stage Heartfield concentrated his attack on "Prussian militarism and the large-scale industries and industrialists who supplied it with arms". (19)

The German novelist, Heinrich Mann, was one of those who saw the significance of the magazine: "The Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung is one of the best of current picture newspapers. It is full in its coverage, technically good, and, above all, unusual and new... Aspects of daily life are seen here through the eyes of the worker, and it is time that this happened. The pictures express complaints and threats reflecting the attitude of the proletariat - but at the same time this proves their self-confidence and their energetic activity to help themselves. The self-confidence of the proletariat in this weary part of the world is most heartening." (20)

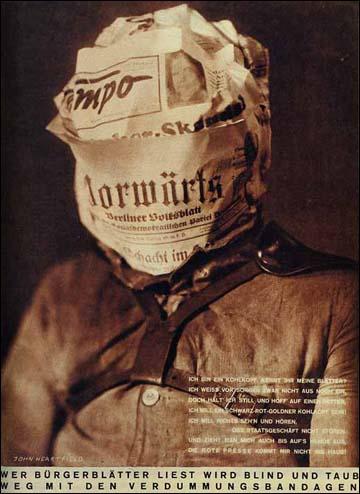

become blind and deaf, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIG) (February 1930)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Heiri Strub worked with Heartfield at the magazine. "Heartfield's high demands of quality made collaboration with him difficult. His long-time colleague, the photographer Janos Reismann, related how Heartfield constantly demanded new pictures until he saw his idea realized... With photographic tricks and painting Heartfield arranged the parts of the photo to fit together seamlessly. With extraordinary care he devised his adhesive picture, so that after final retouching it went straight to the printer. Since the AIZ was produced using the highly sensitive copperplate photogravure method, errors were as evident as the artist's real intention. Heartfield's respect for the skills of others was so great that he himself did not do the photography, and he left the retouching to others, but always under his stringent supervision." (21)

Attacks on Adolf Hitler

Louis Aragon has argued: "John Heartfield is one of those who expressed the strongest doubts about painting, especially its technical aspects... As we know, Cubism was a reaction of painters to the invention of photography. The photograph and the cinema made it seem childish to them to strive for verisimilitude. By means of these new technical accomplishments they created a conception of art which led some to attack naturalism and others to a new definition of reality. With Leger it led to decorative art, with Mondrian to abstraction, with Picabia to the organization of mundane evening entertainment. But toward the end of the war, several men in Germany (Grosz, Heartfield, Ernst) were led through the critique of painting to a spirit which was quite different from the Cubists, who pasted a piece of newspaper on a matchbox in the middle of the picture to give them a foothold in reality. For them the photograph stood as a challenge to painting and was released from its imitative function and used for their own poetic purpose." (22)

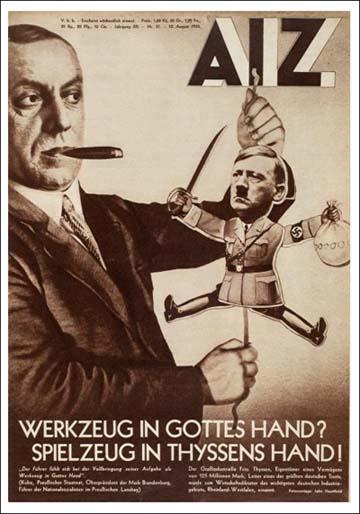

John Heartfield's main target in the early 1930s was Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party. His work often appeared on the front cover of AIG. In 1930 the magazine published twelve of his photomontages. This included one that showed Fritz Thyssen, the owner of United Steelworks, a company that controlled more that 75 per cent of Germany's ore reserves and employed 200,000 people. In the photomontage, Thyssen is shown working Hitler as a puppet.

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

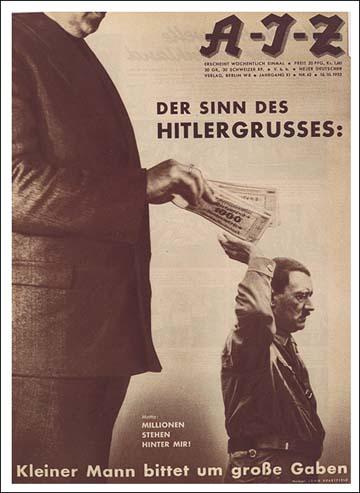

In 1932 Heartfield produced 18 photomontages for AIG. The most famous of these appeared just before the November 1932 General Election. Hitler is showed standing in front of a large man who represents big business. The man is handing over money to Hitler. Printed underneath are the words: "Motto: Millions stand behind me! A little man asks for gifts". Heartfield's friend, Oskar Maria Graf, commented, that all his work was now politically motivated, "the intolerable aspect of events is the motor of his art". (23)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Richard Carline was an English artist who met him during this period: "Slight and little more than five feet tall, Heartfield displayed the unmistakable traits of genius - single-minded and purposeful. With his intense, unpretentious, and uninhibited personality, he warmed toward everyone he met without regard for class or background. He would talk to animals as if they were humans." (24)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

In the election in November 1932 the Nazi Party won 230 seats, making it the largest party in the Reichstag. The German National Party, won nearly a million additional votes. However the German Social Democrat Party (133) and the German Communist Party (89) still had the support of the urban working class and Hitler was deprived of an overall majority in parliament. In numerical terms, the socialist parties obtained 13,228,000 votes compared to the 14,696,000 votes recorded for the Nazis and the German Nationalists. (25)

Chancellor Adolf Hitler

Soon after Hitler became chancellor in January 1933 he announced new elections. Hermann Goering called a meeting of important industrialists where he told them that the election would be the last in Germany for a very long time. He explained that Hitler "disapproved of trade unions and workers' interference in the freedom of owners and managers to run their concerns." (26) Goering added that the NSDAP would need a considerable amount of of money to ensure victory. Those present responded by donating 3 million Reichmarks. As Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary after the meeting: "Radio and press are at our disposal. Even money is not lacking this time." (27)

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag caught fire. When they police arrived they found Marinus van der Lubbe on the premises. After being tortured by the Gestapo he confessed to starting the Reichstag Fire. However he denied that he was part of a Communist conspiracy. Hermann Goering refused to believe him and he ordered the arrest of several leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD).

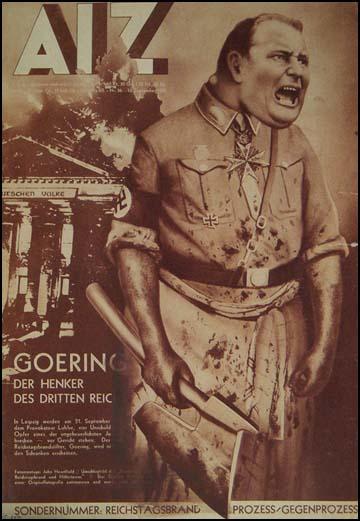

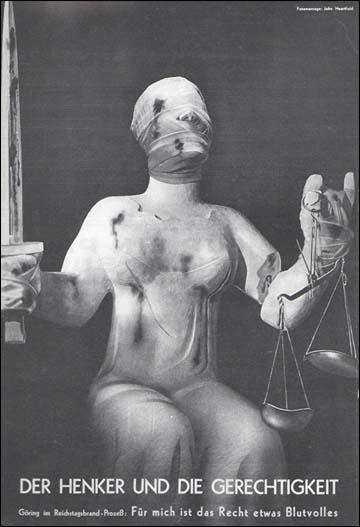

When Hitler heard the news about the fire he gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". KPD candidates in the election were arrested and Hermann Goering announced that the Nazi Party planned "to exterminate" German communists. John Heartfield responded to these events by producing Goering the Executioner of the Third Reich. It shows the "human bloodhound with his axe standing in front of the burning parliament." (28)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Behind the scenes Goering, who was minister of the interior in Hitler's government, was busily sacking senior police officers and replacing them with Nazi supporters. These men were later to become known as the Gestapo. Goering also recruited 50,000 members of the Sturm Abteilung (SA) to work as police auxiliaries. Goering then raided the headquarters of the German Communist Party (KPD) in Berlin and claimed that he had uncovered a plot to overthrow the government. Leaders of the KPD were arrested but no evidence was ever produced to support Goering's accusations. He also announced he had discovered a communist plot to poison German milk supplies. (29)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Thousands of members of the Social Democrat Party and trade union activists were arrested and sent to recently opened concentration camps. Left-wing election meetings were broken up by the Sturm Abteilung (SA) and several candidates were murdered. Newspapers that supported these political parties were closed down during the election. Although it was extremely difficult for the opposition parties to campaign properly, Hitler and the Nazi party still failed to win an overall victory in the election on 5th March, 1933. The Nazi Party received 43.9% of the vote and only 288 seats out of the available 647. The increase in the Nazi vote had mainly come from the Catholic rural areas who feared the possibility of an atheistic Communist government.

John Heartfield in Prague

Adolf Hitler ordered the arrests of all those artists that had criticized him during his rise to power. (30) On 16th April, 1933, members of the Sturmabteilung (SA) arrived at Heartfield's apartment. Heartfield had been warned about what was going to happen and he managed to flee to Prague. This now became the place where AIG was published. That year Heartfield produced 35 front-covers. However, it was very difficult to smuggle the magazine back to Germany and circulation dropped dramatically from the 500,000 copies that were being sold before Hitler took power. (31)

All forms of mass communication were now controlled in Nazi Germany. The man in overall charge was Dr. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda. Lists were drawn up of books the Nazis believed contained "un-German" ideas and then all available copies were publically destroyed. The Nazis were especially hostile to works produced by left-wing writers like Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Toller.

Heartfield was especially upset by the passing of the Enabling Bill. This banned the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party from taking part in future election campaigns. This was followed by Nazi officials being put in charge of all local government in the provinces (7th April), trades unions being abolished, their funds taken and their leaders put in prison (2nd May), and a law passed making the Nazi Party the only legal political party in Germany (14th July). This situation motivated Heartfield to produce the Executioner and Justice on 30th November 1933.

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Adolf Hitler became increasingly annoyed with John Heartfield's photomontages published in Prague (35 in 1933) and he told the government in Czechoslovakia to ban his work. In May 1934 the authorities agreed to Hitler's demands. This created a great deal of controversy and the French artist, Paul Signac, urged international action. He wrote a letter to Heartfield's supporters in Prague: "My whole life long I have been fighting for the freedom of art... I am prepared to contribute my share in organizing a French exhibition of our friend's works... The club is poised for battle against the freedom of the spirit. Let us unite to defend ourselves." (32)

The French poet, Louis Aragon, argued in Commune Magazine: "John Heartfield today knows how to salute beauty. He knows how to create those images which are the beauty of our rage since they represent the cry of the people - the representation of the people's struggle against the brown hangman with his craw crammed with gold pieces. He knows how to create these realistic images of our life and struggle arresting and gripping for millions of people who themselves are a part of that life and struggle. His art is art in Lenin's sense for it is a weapon in the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat." (33)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Heartfield's friends in Europe helped to get his work published. Several photomontages on the Spanish Civil War were published. This included Madrid 1936, a work of art that dealt with the Siege of Madrid. Another poster, The Mothers to their Sons in Franco's Service, was published in December 1936. On the poster it said: "For what you were hired. Whom you are hounding. So permit us mothers to tell you: We grieve for you, young ones. No, we did not raise you to murder. You are allowing yourselves to be abused. You have been betrayed!" (34)

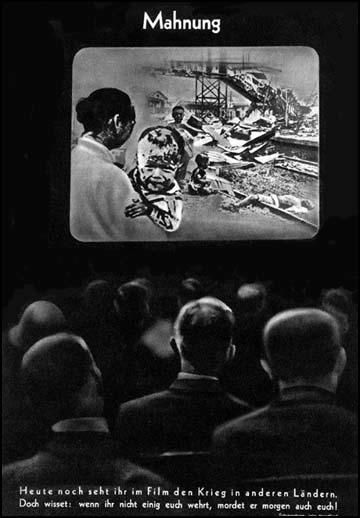

In October 1937 John Heartfield published Warning. In the photomontage an audience looks at a scene of horror caused by Japanese air raids in Manchuria. "Heartfield's pastiche layers in several rows of faceless male heads, backs towards us, beneath the frontal stare of an on-screen victim in the violent newsreel footage at which they are staring: a Chinese mother holding a bloodied child in outsized close-up." (35) It had the caption: "Today you see a film of war in other countries. But remember, if you don't unite to resist it now, tomorrow it will kill you, too!" It was a prediction that was to come true within two years.

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

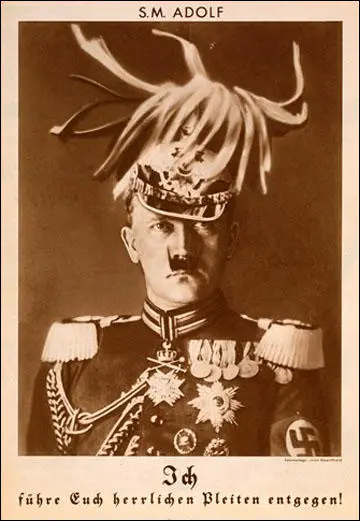

When Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement of 1938 John Heartfield was forced to flee the country. In December he arrived in London. Over the next few months his work appeared in the Reynolds News and Lilliput. He spoke at political rallies, organized anti-Fascist groups, and took part in a successful political cabaret, Four and Twenty Black Sheep. On 23rd September, 1939, Picture Post used one of Heartfield's earlier photomontages, His Majesty Adolf, which showed Hitler wearing the Kaiser's uniform and moustache, on its front-cover. (36)

Second World War

On the outbreak of the Second World War he was interned with fellow refugees who had suffered under the Nazis and were now dubbed "enemy aliens". He was suffering from poor health and he was eventually released but he was not asked to work for the British government. "His whole ambition was to make people fully aware of the menace of Fascism and to expose the Nazi tyranny through his work as an artist... The powerful contribution he might have made toward the Allied victory through his mastery of satire was not acceptable to the British authorities. They were highly suspicious of art, especially experimental forms of art by a German refugee." (37)

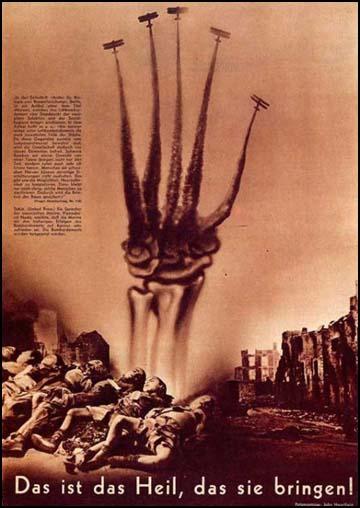

One of John Heartfield most powerful photomontages, This is the Salvation that they Bring!, that had originally been published in protest against the Spanish Civil War, was republished during the Blitz. On the poster it had an extract from an article that appeared in the Nazi Party funded Berlin Journal for Biology and Race Research: "The densely populated sections of cities suffer most acutely in air raids. Since these areas are inhabited for the most part by the ragged proletariat, society will thus be rid of these elements. One-ton bombs not only cause death but also very frequently produce madness. People with weak nerves cannot stand such shocks. That makes it possible for us to find out who the neurotics are. Then the only thing that remains is to sterilize such people. Thereby the purity of the race is guaranteed." (38)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

John and his third wife, Gertrud (Tutti) Heartfield, settled in Hampstead. During the war he was an active member of the Artists International Association and contributed to its exhibitions. Heartfield also designed book jackets for the London publisher Lindsay Drummond and Penguin Books. (39)

East Germany

John Heartfield and his wife moved to Leipzig in East Germany in August 1950. Together with his brother, Wieland Herzfelde, he worked for publishers and organizations in the GDR. He also designed scenery and posters for the Berliner Ensemble and the Deutsches Theatre. However, as Peter Selz has pointed out, he found it difficult to produce political photomontages. "While he was celebrated as a cultural leader, his chief idiom, photomontage, was still suspect during the 1950s among the more orthodox advocates of socialist realism." (40)

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

Heartfield continued to be a peace activist and on 9th June 1967, at the time of an exhibition of his works at the Stockholm Modern Museum, he wrote about the dangers posed by the Vietnam War. "Since we are living in the nuclear age, a third world war would mean a catastrophe for all mankind, a catastrophe the full extent of which cannot be possibly be imagined.... The war of extermination against the Vietnamese people, fighting heroically for their existence... Now there is a war in the Middle East! Shortly before that, a monarchist-fascist putsch smothered every democratic political movement in Greece. The flames are licking at your doorstep! Today peace-loving men of all nations must work together even more closely; must mobilize all the resources to strengthen and preserve world peace, since powerful rulers again lust for war." (41)

John Heartfield died in Berlin on 26th April, 1968.

John Heartfield Photomonteur Digital Archive

Primary Sources

(1) Louis Aragon, Commune Magazine (May 1935)

John Heartfield is one of those who expressed the strongest doubts about painting, especially its technical aspects. He is one of those who recognized the historical evanescence of that kind of oil-painting which has only been in existence for a few centuries and seems to us to be painting per se, but which can abdicate at any time to a technique which is new and more in accord with contemporary life, with mankind today. As we know, Cubism was a reaction of painters to the invention of photography. The photograph and the cinema made it seem childish to them to strive for verisimilitude. By means of these new technical accomplishments they created a conception of art which led some to attack naturalism and others to a new definition of reality. With Leger it led to decorative art, with Mondrian to abstraction, with Picabia to the organization of mundane evening entertainment.

But toward the end of the war, several men in Germany (Grosz, Heartfield, Ernst) were led through the critique of painting to a spirit which was quite different from the Cubists, who pasted a piece of newspaper on a matchbox in the middle of the picture to give them a foothold in reality. For them the photograph stood as a challenge to painting and was released from its imitative function and used for their own poetic purpose....

John Heartfield today knows how to salute beauty. He knows how to create those images which are the very beauty of our age since they represent the cry of the people-the representation of the people's struggle against the brown hangman with his craw crammed with gold pieces. He knows how to create these realistic images of our life and struggle arresting and gripping for millions of people who themselves are a part of that life and struggle. His art is art in Lenin's sense for it is a weapon in the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat.

John Heartfield today knows how to salute beauty. Because he speaks for the countless oppressed people throughout the world, and this without depreciating for a moment the magnificent tone of his voice, without debasing the majestic poetry of his tremendous imagination. Without diminishing the quality of his work. Master of a technique entirely of his own invention, a technique which uses for its palette the whole range of impressions from the world of actuality; never imposing a rein on his spirit, blending his figures at will, he knows no signpost other than dialectical materialism, none other than the reality of the historical process, which he, filled with the anger of battle, translates into black and white.

(2) George Grosz interviewed by Erwin Piscator (1928)

When John Heartfield and I invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o'clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it.

(3) Bertolt Brecht, discussing the origins of photomontage in 1949.

John Heartfield is one of the most important European artists. He works in a field that he created himself, the field of photomontage. Through this new form of art he exercises social criticism. Steadfastly on the side of the working class, he unmasked the forces of the Weimar Republic driving toward war; driven into exile he fought against Hitler. The works of this great artist, which mainly appeared in the workers' press, are regarded as classics by many, including the author of these lines.

(4) George Grosz, The Autobiography of George Grosz (1955)

He (Wieland Herzfelde) was small of stature, just like his brother John Heartfield. During the First World War, Wieland published a literary journal, Die Neue Jugend - work on which was repeatedly interrupted by bouts of military service. The journal carried poems by Wieland's friends and some of my drawings.

When Wieland was called to the front once again, a new man joined the editorial board: the boisterous poet Franz Jung. Die Neue Jugend at once assumed a new face: it became aggressive. Its new format was based on that of American journals, and Heartfield used collages and bolder type to develop a new style.

Wieland, unlike most of us, was an optimist at heart. He believed that the masses - not only himself - would make a stand, for he imagined that everyone was endowed with his own trusting and noble nature. He devoted more and more of his time to politics, wrote fewer poems, left Dada to its own devices and founded a publishing house he called the Malik Verlag.

All that stopped, of course, when Hitler came to power. Wieland became a refugee like a hundred thousand others.

(5) Anthony Coles, John Heartfield: 1891-1968 (1975)

One must examine the way in which Heartfield's montages worked and in some way assess their reception and success. Put at its simplest, either Heartfield was preaching to the converted or he was preaching in order to convert - for he was definitely preaching. Modern art, created in the belief of art for art's sake, does the former. Those who believe in a necessary spiritual detachment of art from other human activities have their beliefs understandably reinforced by works of art produced, either consciously or by default, precisely for that purpose. The only level on which Heartfield can be said to be preaching to the converted is that of reinforcement or confirmation of ideology either by direct criticism of ideologies contrary to his, or by the presentation of aspects of the ideology to which he subscribed as praiseworthy.

This process of ideological reinforcement is an essential one in art and operates in two ways. Firstly, the image is used to confirm an existing belief. Viewers have their beliefs reinforced by being able to bask in reflected glory. Secondly, ideological back-sliders are reminded of the consequences of their back-sliding. In this case some theoretical expertise on the part of the audience can be assumed and the picture can therefore be made to operate on a relatively sophisticated level without quantities of explanatory material. This is the reason for the continuing comprehensability of Heartfield's work, which is usually shown with the original explanatory material missing.

However, the main purpose of Heartfield's work is preaching to convert, and there are a number of ways in which he did this extremely successfully. Firstly, he used photographs and the technique of photomontage -.a technique of which he was one of the more skilful proponents. The democratic nature of photography was recognised very early.... The relative cheapness of the photograph and resulting printed images makes wide distribution possible and thus photography became the most important tool of information distribution before television, which is in itself

only an extension of photography. Equally early arose the myth that the camera does not lie and thus photographs came to have a documentary power. Even when it is known that a picture is posed or faked it is still regarded as an accurate record. Thus Heartfield could produce the most intellectually convoluted images by montage and still the final product would retain its power as a photographic image. It has rightly been pointed out that many of Heartfield's montages would have looked ludicrous had they been just drawn or painted.

(6) John Heartfield, The Mothers to their Sons in Franco's Service (December, 1936)

I bore you under the palm trees of Morocco...

I sent you to school in Hamburg...

I hugged you, my child, in Rome...

And now?

You speak in foreign tongues,

Cannot ask one another,

For what you were hired,

Whom you are hounding.

So permit us mothers to tell you:

We grieve for you, young ones.

No, we did not raise you to murder.

You are allowing yourselves to be abused. You have been betrayed!

The enemies against whom you have been sent

Are enemies of the poverty that also troubles us,

Are enemies of the war that threatens the world.

You risk your lives. Risk more! Dare to think!

Refuse to execute your brothers!

Damned be your obedience, your false courage!

Don't you know what you are doing?

Our blood sticks to your weapon.

(7) Heiri Strub, An Art for the Revolutionary Struggle (1972)

Heartfield always considered his photomontages as artistic achievements. He took in stride the fact that he was not recognized by contemporary art critics. The works he created for dissemination in huge editions had no value in the art market. Directing his political charges at the masses, he could scarcely count on a sympathetic reaction from bourgeois art collectors. The worker, however, for whom he intended his photomontages, understood their revolutionary content, but assigned no artistic value judgment to them.

Why, then, did he take such great care with each work? Why this strong sense of artistic responsibility for ephemeral political propaganda? Artistic quality, for Heartfield, was identical with the clear solution of a concept, with the purposeful accomplishment of the substance and form of an idea. The graphic means, the distribution of space, the proportions, the choice of lettering, the tonal quality or the color of the photograph were subordinated to this. Every detail was a part of the expression.

Student Activities

John Heartfield v Adolf Hitler: Censorship in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)