Enabling Bill

In May 1932 General Hans von Seeckt joined up with Alfred Hugenberg, Hjalmar Schacht, and several industrialists, to call for the uniting of the parties of the right. They demanding the resignation of Heinrich Brüning. Germany's president, Paul von Hindenburg, agreed and forced him to leave office and on 1st June he was replaced as chancellor by Franz von Papen. The new chancellor was also a member of the Catholic Centre Party and, being more sympathetic to the Nazis, he removed the ban on the SA. The next few weeks saw open warfare on the streets between the Nazis and the Communists during which 86 people were killed. (1)

Just a week after taking office, Papen arranged a meeting with Hitler. He later recalled: "I found him curiously unimpressive. I could detect no inner quality which might explain his extraordinary hold on the masses... He had an unhealthy complexion, and with his little moustache and curious hair style had an indefinable bohemian quality. His demeanour was modest and polite... As he talked about his party's aims I was struck by the fanatical insistence with which he presented his arguments. I realized that the fate of my Government would depend to a large extent on the willingness of this man and his followers to back me up, and that this would be the most difficult problem with which I should have to deal." (2)

In an attempt to gain support for his new government, in July, 1932. Papen called another election. Hitler made speeches in 53 towns and cities. His main theme was his party was the only one that could rescue the German people from its misery. The Nazi Party won 230 seats, making it the largest party in the Reichstag. However the German Social Democrat Party (133) and the German Communist Party (89) still had the support of the urban working class and Hitler was deprived of an overall majority in parliament. (3)

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "We have won a tiny bit... Now we must come to power and exterminate Marxism. One way or another! Something must happen. The time for opposition is over. Now deeds! Hitler is of the same opinion. Now events have to sort themselves out and then decisions have to be taken. We won't get to an absolute majority this way." (4)

The British Ambassador, Horace Rumbold, sent a message to John Simon, the British foreign secretary: "Hitler seems now to have exhausted his reserves. He has swallowed up the small bourgeois parties of the Middle and the Right, and there is no indication that he will be able to effect a breach in the Centre, Communist, and Socialist parties... All the other parties are naturally gratified by Hitler's failure to reach anything like a majority on this occasion, especially as they are convinced that he has now reached his zenith." (5)

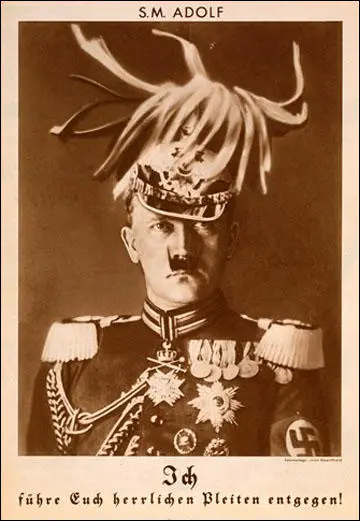

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

The behaviour of the NSDAP became more violent. On one occasion 167 Nazis beat up 57 members of the German Communist Party in the Reichstag. They were then physically thrown out of the building. The stormtroopers also carried out terrible acts of violence against socialists and communists. In one incident in Silesia, a young member of the KPD had his eyes poked out with a billiard cue and was then stabbed to death in front of his mother. Four members of the SA were convicted of the rime. Many people were shocked when Hitler sent a letter of support for the four men and promised to do what he could to get them released. (6)

Incidents such as these worried many Germans, and in the elections that took place on 6th November, 1932 the support for the Nazi Party fell and the number of seats in the Reichstag was reduced from 230 to 196. The German Communist Party made substantial gains in the election winning 100 seats. Hitler used this to create a sense of panic by claiming that German was on the verge of a Bolshevik Revolution and only the NSDAP could prevent this happening. (7)

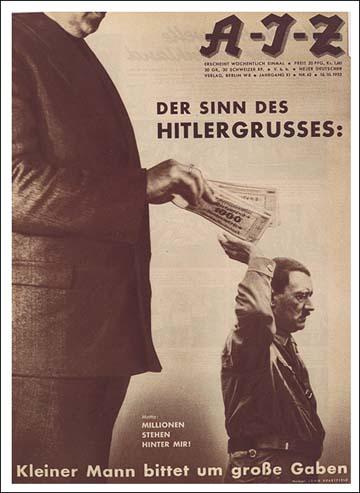

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

A group of prominent industrialists, including Fritz Thyssen, Albert Voegle and Emile Kirdorf, who feared such a revolution, had a meeting to discuss this issue and after agreeing on a united political strategy, sent a petition to Paul von Hindenburg asking for Hitler to become Chancellor. On 19th November, President Hindenburg met with Hitler but they failed to get agreement and Kurt von Schleicher was appointed chancellor. (8)

In an effort to undermine Hitler, Schleicher offered the vice-chancellorship of Germany to Gregor Strasser. Hitler was furious and began to abandon his strategy of disguising his extremist views. In one speech he called for the end of democracy a system which he described as being the "rule of stupidity, of mediocrity, of half-heartedness, of cowardice, of weakness, and of inadequacy." (9)

On 4th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler had a meeting with Franz von Papen and decided to work together for a government. It was decided that Hitler would be Chancellor and Von Papen's associates would hold important ministries. "They also agreed to eliminate Social Democrats, Communists, and Jews from political life. Hitler promised to renounce the socialist part of the program, while Von Papen pledged that he would obtain further subsidies from the industrialists for Hitler's use... On 30th January, 1933, with great reluctance, Von Hindenburg named Hitler as Chancellor but refused him extraordinary powers." (10)

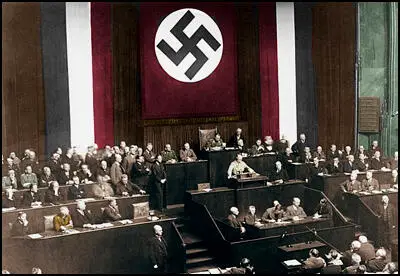

After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party, were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill. (11)

Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party became banned organisations. Party activists still in the country were arrested. A month later Hitler announced that the Catholic Centre Party, the Nationalist Party and all other political parties other than the NSDAP were illegal, and by the end of 1933 over 150,000 political prisoners were in concentration camps. Hitler was aware that people have a great fear of the unknown, and if prisoners were released, they were warned that if they told anyone of their experiences they would be sent back to the camp. (12)

It was not only left-wing politicians and trade union activists who were sent to concentration camps. The Gestapo also began arresting beggars, prostitutes, homosexuals, alcoholics and anyone who was incapable of working. Although some inmates were tortured, the only people killed during this period were prisoners who tried to escape and those classed as "incurably insane". (13)

Primary Sources

(1) Colin Cross, Adolf Hitler (1973)

It was seven days after the fire that, on March 5th, 1933, Germany went to the polls in the last contested election of the Weimar republic. Especially in the closing stages, almost the only propaganda that existed was in favour of the National Socialists who organised marches, lit `liberation bonfires' on hill-tops and along the Rhine valley, and monopolised the radio. In Berlin, loudspeakers were set up in the streets to relay Hitler's speeches and to ensure that 'the last slumberer awakes'. On top of this was outright intimidation of the opposition both by formal bans on their meetings and unofficial violence by stormtroopers.

Yet it was still a free election in that any party was allowed to put up candidates and the voting procedures and secret ballot remained inviolate. The electorate turned out in record numbers; 88.8 per cent of those entitled to vote went to the polls and this was the highest proportion in the history of the Weimar republic.

The result must have been a disappointment to Hitler. On February 28th he had told his cabinet that he expected the Reichstag fire to ensure that he would win at least 51 per cent of the vote; such an absolute majority would have been of supreme moral value to him in legitimising a dictatorship. He wanted victory on the scale of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States, who had won 57.4 per cent of the popular vote in the crisis election of 1932, or of the MacDonald-Baldwin coalition who in Britain in comparable circumstances in 1931 had won 67 per cent.

(2) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962)

Hitler's dictatorship rested on the constitutional foundation of a single law. No National or Constitutional Assembly was called and the Weimar Constitution was never formally abrogated. Fresh laws were simply promulgated as they appeared necessary. What Hitler aimed at was arbitrary power. It took time to achieve this, but from the first he had no intention of having his hands tied by any constitution; there was no equivalent of the Fascist Grand Council which in the end was used to overthrow Mussolini. Long before the Second World War, even the Cabinet had ceased to meet in Germany.

The fundamental law of the Hitler 'regime was the so-called Enabling Law (Law for Removing the Distress of People and Reich). As it represented an alteration of the Constitution, a majority of two-thirds of the Reichstag was necessary to pass it, and Hitler's first preoccupation after the elections was to secure this. One step was simple: the eighty-one Communist deputies could be left out of account, those who had not been arrested so far would certainly be arrested if they put in an appearance in the Reichstag. Negotiations with the Centre were resumed and, in the meantime, Hitler showed himself in his most conciliatory mood towards his Nationalist partners. Both the discussions in the Cabinet' and the negotiations with the Centre, revealed the same uneasiness at the prospect of the powers the Government was claiming. But the Nazis held the whip-hand with the decree of 28 February. If necessary, they threatened to make sufficient arrests to provide them with their majority without bothering about the votes of the Centre. The Nationalists comforted themselves with the clause in the new law which declared that the rights of the President remained unaffected. The Centre, after receiving lavish promises from Hitler, succeeded also in getting a letter from the President in which he wrote that "the Chancellor has given me his assurance that, even without being forcibly obliged by the Constitution, he will not use the power conferred on him by the Enabling Act without having first consulted me."

(3) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987)

Enabling Law. The first law submitted to the Hitler controlled Reichstag, on 23 March 1933, was a `Law for removing the distress of People and Reich'. A sweeping measure to enable the new government to make laws without the approval of the Reichstag, it was passed with a two-thirds majority. The 441-84 vote in favour was undoubtedly achieved by the exclusion of the Communists and by the intimidating presence of S A men in the Kroll Opera House, where the Reichstag was sitting. The failure of the Centre Party to vote against the Enabling Law was crucial. Five articles of the Act destroyed what was left of the German constitution. Article 1 transferred legislation from the Reichstag to the government. Article 2 gave the administration full power to make constitutional changes. Article 3 transferred from President to Chancellor the right to draft laws. Article 4 provided that the terms of the Enabling Act applied to treaties with foreign states. Article 5 required renewal in four years. The Enabling Law (renewed in 1937, 1939 and 1942) was followed by the process of Gleichschaltung, which replaced parliamentary power by Nazi power. The Reichstag continued in existence as a constitutional fiction, meeting only a dozen times up to 1939. It passed only four laws, all without a vote, and the only speeches it heard were those of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi leadership.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Who Set Fire to the Reichstag? (Answer Commentary)

Appeasement (Answer Commentary)