Picture Post

Picture Post, a magazine that pioneered photojournalism, was edited by Stefan Lorant, when it was first published in 1938 by Edward G. Hulton. The magazine was an immediate success and after four months was selling 1,350,000 copies a week.

When Lorant emigrated to the United States in 1940 Tom Hopkinson took over as editor. Hopkinson recruited a team of talented writers and photographers including Tom Winteringham, Macdonald Hastings, Maurice Edelman, Walter Greenwood, Vernon Bartlett, A. L. Lloyd, Anne Scott-James, James Cameron, Robert Kee, Sydney Jacobson, Ted Castle, Bert Hardy and Kurt Hutton.

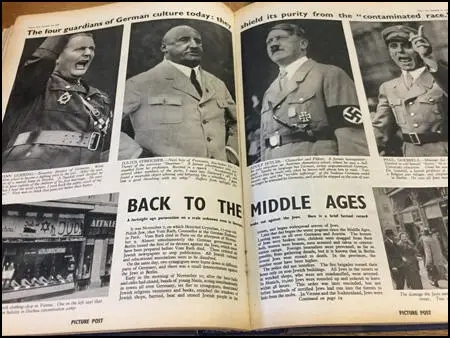

Hopkinson used the Picture Post to campaign against the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany. In the journal published on 26th November 1938, he ran a picture story entitled Back to the Middle Ages. Photographs of Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, Herman Goering and Julius Steicher were contrasted with the faces of those scientists, writers and actors they were persecuting.

In January 1941 Tom Hopkinson published his Plan for Britain. This included minimum wages throughout industry, full employment, child allowances, a national health service, the planned use of land and a complete overhaul of education. This document led to discussions about post-war Britain and was the forerunner of the Beveridge Report that was published in December 1943.

The sales of the Picture Post increased rapidly during the Second World War and by December 1943 the magazine was selling 950,000 copies a week. The trend continued after the war and by the end of 1949 circulation reached 1,422,000 with profits of over £2,500 a week.

Tom Hopkinson was often in conflict with Edward G. Hulton, the owner of Picture Post. Hulton supported the Conservative Party and objected to Hopkinson's socialist views. In August 1945 Hulton wrote to Hopkinson telling him that "I cannot permit editors of my newspapers to become organs of Communist propaganda. Still less to make the great newspaper which I built up a laughing-stock."

In 1950 Hopkinson sent James Cameron and Bert Hardy to report on the Korean War. While in Korea the two men produced three illustrated stories for Picture Post. This included the landing of General Douglas MacArthur and his troops at Inchon. Cameron also wrote a piece about the way that the South Koreans were treating their political prisoners. Edward G. Hulton considered the article to be "communist propaganda" and Hopkinson was forced to resign.

Ted Castle took over as editor but several journalists, including James Cameron and A. L. Lloyd, refused to continue working for the magazine. Cameron commented: "In fact Picture Post soon painlessly surrendered all the values (after Tom Hopkinson left) and purposes that had made it a journal of consideration, before the eyes ot its diminishing public it drifted into the market of arch cheesecake and commonplace decoration, and by and by it died, as by then it deserved to do."

When Tom Hopkinson left the Picture Post it was selling over 1,380,000 copies a week. By June 1952 it had fallen to 935,000. Sales continued to decline and by the time the magazine was closed in May 1957 circulation was less than 600,000 copies a week.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Hopkinson, Picture Post: 1938-50 (1970)

The idea of Picture Post - most British of magazines - came from abroad. Its first editor, Stefan Lorant, was a Hungarian Jew - one of a small and brilliant band who left their country after the First World War because they found its political climate oppressive, and Hungary too small to give scope to their talents; and the paper's two first cameramen, Hans Baumann (or Felix H. Man as he signed himself) and Kurt Hubschmann (K. Hutton), were both Germans who had mastered their craft on magazines in Berlin and Munich.

The original conception owed everything, to Lorant. I met him first, four years before Picture Post was launched, when he turned up at Odhams Press where I then worked, with a suggestion for starting a picture magazine. This was in June 1934, and he arrived at one of very few moments in Odhams' history when an original idea had a chance of being accepted.

(2) Picture Post (26th November, 1938)

It was November 7, on which Herschel Grynsban, 17-year-old Polish Jew shot Vom Rath, Counsellor at the German Embassy in Pans. Vom Rath died in Paris on the afternoon of November 9. Almost simultaneously the German government in Berlin issued the first of its decrees against the Jews, which must have been prepared before Vom Rath died. These ordered all Jewish newspapers to stop publication. All Jewish cultural and educational associations were to be dissolved

On the same day, two synagogues were burnt down in different parts of Germany, and there was a small demonstration against the Jews in Berlin.

Early in the morning of November 10, after the beer hall and cafes had closed bands of young Nazis, acting simultaneously in towns all over Germany, set fire to synagogues, desecrated Jewish religious vestments and books, smashed the windows of Jewish shops, harried, beat and stoned Jewish people in the streets, and began widespread arrests of Jews.

Later that day began the worst pogrom since the Middle Ages. Looting went on all over Germany and Austria. The houses of Jews were broken into, children were dragged from their beds, women were beaten, men arrested and taken to concentration camps. Foreign journalists were prevented, as far as possible, from gathering details, but it is known that in Berlin several Jews were stoned to death. In the provinces, the number must have been higher.

The police did not interfere. The fire brigades turned their hoses only on non-Jewish buildings. All Jews in the streets or in wrecked shops, who were not manhandled, were arrested. In Munich, 10,000 Jews were rounded up and ordered to leave within 48 hours.

(3) Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time (1982)

A picture story 'Back to the Middle Ages', in which the most ferocious portraits of the Nazi leaders - Hitler, Goering, Goebbels, Julius Streicher the chief Jew-baiter - were contrasted with the faces of those scientists, writers and actors they were persecuting. Out of all the thousands of picture magazines I have since read and studied, this remains for me the most powerful example of photographs used for political effect. The photographs become cartoons, hammering home their point more effectively than pages of argument and rhetoric.

(4) Picture Post (May, 1940)

May 22, 1940: The darkest day of the war. Arras and Amiens fall to the German mechanised forces. Through the corridor between these two towns, large motor-cycle detachments roar on to Abbeville and seize it. The Germans claim that the fall of Le Touquet can be expected at any minute. The enemy, moving at incredible speed, has reached the Channel. The Allied Armies have been bitten in two. The Corridor between them, now thirty miles wide, is a charred thoroughfare for tanks and motorised divisions, patrolled by clouds of low-flying planes. The Germans, streaking on north up towards Boulogne and Calais, are making a bid for the total encirclement of the Northern Allied Army. Can that fatal corridor between Arras and Amiens be closed? The world waits for the answer on which so much depends.

In France, the weight of German planes is loading the scales against civilisation. At home, Lord Beaverbrook, the new Minister for Aircraft Production, asks aircraft factories to work seven days a week, 24 hours a day. At last it is being realised that minutes saved mean planes gained. And that only planes mean survival.

May 22, 1940: Arras is recaptured by the French. The British counter-attack between Arras and Douai. The Belgians are holding the line. But the German thrust towards the coast continues, spreading terror and destruction behind the Allied lines.

The answer comes. In a little under three hours. Parliament passes the most revolutionary measure in its history. The Government is given complete control of all persons and all property in the country. Banking, munitions firms, wages, profits, hours and conditions of service are all brought at once under Government control.

Herbert Morrison, the new Minister of Supply, subsequently announces that the Government is taking over full control of all armament works. For these concerns the-Excess Profits Tax is raised to 100 per cent.

(5) Tom Winteringham, Picture Post (21st September, 1940)

As I was watching yesterday 250 men of the Home Guard take their places for a lecture at the Osterley Park Training School an air-raid siren sounded, and a dozen men with rifles moved to their prearranged positions as a defence unit against low-flying aircraft.

The lecturer began to talk of scouting, stalking and patrolling. And as I watched and listened I realised that I was taking part in something so new and strange as to be almost revolutionary - the growth of an "army of the people" in Britain - and, at the same time, something that is older than Britain, almost as old as England - a gathering of the "men of the counties able to bear arms."

The men at Osterley were being taught confidence and cunning, the use of shadow and of cover, by a man who learned field-craft from Baden-Powell, the most original irregular soldier in modern history (with the possible exception of Lawrence of Arabia). And in an hour or two they would be hearing of the experience, hard bought with lives and wounds, won by an army very like their own, the army that for year after year held up Fascism's flood-tide towards world power, in that Spanish fighting which was the prelude and the signal for the present struggle. I could not help thinking how like these two armies were: the Home Guard of Britain and the Militia of Republican Spain. Superficially alike in mixture of uniforms and half-uniforms, in shortage of weapons and ammunition, in hasty and incomplete organisation and in lack of modem training, they seemed to me more fundamentally alike in their serious eagerness to learn, their resolve to meet and defeat all the difficulties in their way, their certainty that despite shortage of time and gear they could fight and fight effectively.

The school that they were attending had in a way been made by themselves. Two or three months ago, when this newest army in the world was first proposed, I wrote two articles in Picture Post on ways to meet invasion, on the experiences of Spain, and on the first rough steps to be taken for the training of a new force. So many queries piled into the offices of Picture Post, so many requests for more teaching and more detail, that it was natural for Mr. Edward Hulton to think of

the idea of a school for the Home Guard - or, as they were then, the L.D.V. Osterley was a Picture Post idea, and Osterley has given free training to over 3,000 of the Home Guard at Edward Hulton's expense. The same evening that he decided to go ahead with the idea, he got in touch with Lord Jersey, who permitted us to use the grounds of his famous park at Osterley.

On July 10 the first course was given at the school. Our aim was then to give 60 members of the Home Guard two days' training three times a week. By the end of July over 100 men were attending each course, 300 a week. The numbers rose sharply in August; during the week when this was written one of the courses included 270 men.

Those attending the school in July were nearly a thousand; those attending in August over 2,000; the September figures will probably be around 3,000. We could not keep them away with bayonets - if we had any.

But all was not plain sailing; there were prejudices to be broken down. Soon after the school was founded an officer high up in the command of the L.D.V. requested Mr. Hulton and myself to close the school down, because the sort of training we were giving was "not needed." This officer explained to us with engaging frankness that the Home Guard did not have to do "any of this crawling round; all they have to do is to sit in a pill-box and shoot straight." The "sit in a pillbox" idea, a remnant of the Maginot Line folly not yet rooted out of the British Army, met us on other occasions.

(6) Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time (1982)

At Picture Post we had come to know Tom Wintringham, who had gained experience of German methods of warfare while fighting for the International Brigade in Spain. He was also an excellent writer with a clear style and a vigorous outlook, and in a series of articles during May and June had established himself as the mouthpiece of new ideas and methods of guerrilla warfare. Since these depended little on square-bashing or highly organized staff work - and much on adaptability, local knowledge and ability to live off the country - they made a strong appeal to the freebooting spirit of the day and to the general determination to 'get stuck into things' without waiting for someone in Whitehall to issue permits in triplicate.

(7) Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time (1982)

In publishing our 'Plan for Britain' so early in the war, Picture Post was taking the lead in what was to become one of the most controversial issues over the next years - that of war aims. Churchill himself was strongly against any discussion of war aims: Britain, he declared, had only one war aim, to defeat Hitler - and his position was understandable. He led a motley coalition; most of his ministers came from the Conservative ranks - in which at this time he himself had no secure roots - but there were also Labour and Liberal members of his cabinet. Winning the war appeared to him the only issue on which all could remain united; over discussion as to what Britain should be like when the war ended they would quite certainly fall apart. But though this might be a good reason for the government to keep silent about the future, it did not stop ordinary men and women - particularly those in the forces with time on their hands - from thinking and talking about it a great deal.

The result of our special issue, therefore, was twofold. It intensified support among readers, who looked upon the magazine as their mouthpiece, almost indeed as their own property, and it increased the antagonism felt in certain government departments, above all in the Ministry of Information.

(8) In Picture Post the editor Tom Hopkinson criticized the standard of public shelters in Britain (November 1940)

One small Salvation Army canteen hands out penny cups of tea (the queue may be a hundred long). One water-tap serves all these thousands. And the sanitation? A handful of lavatory buckets in the dark, behind a canvas screen. And all this while good shelters are shut to the people big business buildings, vast pyramids of steel and concrete, deep below which is a labyrinth of rooms and passages which could shelter thousands, are locked to the public at night, and great notices are posted outside, saying, 'This is not a Public Shelter'.

(9) Tom Winteringham, Picture Post (20th December 1941)

We have an army that is very good. As Churchill has told us, it began this job with equality on the ground and superiority in the air. Can Mr Churchill find leaders for it who will understand what Rommel was being taught from 1935? Can we find a staff worthy of the fighting men and commanders? That is the key question raised by the fighting in Libya, and what we know as yet of how that important battle has gone.

(10) Tom Hopkinson, Picture Post (February, 1943)

The House of Commons has said its say. It has not precisely rejected the Beveridge Report - indeed, so far as words go, it gave it a kind of welcome. It has not even quite killed the Report. It has done something different. It has filleted it. It has taken out the backbone and the bony structure. It has added up the portions that are left - and assured us that they amount to 70%. Sixteen portions out of twenty-three by the Herbert Morrison reckoning - and the only proviso attached is that none of these portions is quite definitely and finally guaranteed. The opponents of the Report - from Sir John Anderson all the way down to Sir Herbert Williams - spoke as though the basis of the Report were an attempt to cadge money off the rich on behalf of the not entirely deserving poor.

Yes. They might be willing to give something. They recognized the justice of the claim. But not all that was asked. And certainly not now. And, above all, they could not make promises for the future. Sir Arnold Gridley wondered "how want is to be defined. Can it necessarily be met by any specific monetary sum? The family of a hard-working and thrifty man can live without want, perhaps on £3 a week, whereas the family of a man who misuses his money or spends it on drink or gambling, may be very hard put to it if his wages are £5 or £6 a week."

The fear that small children or old age pensioners may take to drink or gambling is a very real one to large sections of the Conservative Party.

Sir lan Fraser congratulated the Chancellor on having "done a most difficult thing". He had called the House back "from the fancy fairyland in which it loves to indulge, to reality, and thereby rendered a great service to us all." Further on in his speech Sir LAN carried misrepresentation to the pitch of mania. Objecting to Sir William's plan to make insurance compulsory and national, so as to cut the cost of collection to a fraction, he declared that Sir William's object in doing this was "to steal a capital asset so as to get some revenue for his scheme".

Finally, Sir Herbert Williams let out of his own private bag the largest cat released on the floor of the House of Commons since Baldwin explained why he had to fight the 1935 election on a lie. He did it with the words "If the scheme is postponed until six months after the termination of hostilities the then House of Commons will reject it by a very large majority." Exactly. If we don't get the foundations of a new Britain laid while the war is on, we shall never get them laid at all. Sir Herbert Williams and others of the same kind - or nearly the same kind - will see to that. For so huge an indiscretion the Conservative Party should un-knight Sir Herbert instantly.

These snivelling objections are quoted for one purpose only: to show the low level at which the opponents of the Report chose to conduct the battle. They fought it on the Poor Law level, the three ha'penny, ninepence-for-fourpence, Kingsley Wood and Means Test level. The common people of this country were asking for more than their directors and controllers chose to give them. They could get back where they belonged, and say thank-you the mercies were no smaller.

(11) Maurice Edelman, Picture Post (9th June, 1945)

A new spirit had taken hold of the Labour Party. You felt it m the first hours of the Blackpool Conference. It expressed itself in the faces and voices of the delegates who came to the microphone. It communicated itself to the Executive.

(12) Robert Kee, Picture Post (3rd July, 1948)

Although there are no official figures, the coloured population of Great Britain is estimated by both the Colonial Office and the League of Coloured People at about 25,000, including students. This total is distributed over the whole of Britain, but there are two large concentrated communities: one of about 7000 in the dock area of Cardiff round London Square, popularly known as 'Tiger Bay', and the other of about 8000 in the shabby mid-nineteenth century residential South End of Liverpool. It is most important to remember that all colonial coloured people, of whatsoever origin or class, have been brought up to think of Britain as 'The Mother Country'. This is particularly true of the West Indians, who no longer have the tribal associations and native language which can still provide some fundamental security for the disillusioned African. The West Indian disillusioned with Britain is deprived of all sense of security. He becomes, quite understandably, the most sensitive and neurotic member of the coloured community.

For Britain's colour problem there are a few practical and remedial steps that can be taken. But it can only be solved By a true integration of white and coloured people in one society. And for that to take place there must be some sort of revolution inside every individual mind - coloured and white - where prejudices based on bitterness, ignorance or patronage have been established.

(13) Edward G. Hulton, Picture Post (February, 1950)

Nearly everybody is now persuaded that the Soviet Government constitutes a grave menace, not only to Peace, but to our very lives. The Soviet Government, with the Communist Party, is what Mr. Churchill would rightly call 'a relentless foe' - determined on the complete destruction of all peoples who will not obey their dictates one hundred per cent. Although it may very well be true that the Kremlin does not desire war at this particular moment, this is merely because it is waiting, crouching, for a better opportunity to spring upon us. All and every form of appeasement is worse than vain.

At this perilous moment, I am, personally speaking, appalled that the conduct of our foreign policy should be in the hands of Mr. Ernest Bevin.

(14) Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time (1982)

The winter of 1949-50 passed quietly enough, but early in 1950 I began to be bombarded with complaints, first, the familiar ones from Edward Hulton expressing anxiety over the Communist danger and his conviction that Picture Post was "too left-wing". At the same time there started to reach me from management criticism of a different kind: that the paper had lost all vitality, readers were now finding it dull and uninspiring, out of touch with the lively new spirit of the times. Some of the photographs were too large, some too small; other ought not to have appeared in any size. I was advised to study the popular weeklies. Weekend and Reveille, and told that if I would only print similar articles and pictures we could soon double our circulation.

I answered that if we were to imitate such totally different magazines we should destroy the reputation so carefully built up and be more likely to halve our readership than double it. This uncooperative attitude was put down to my always wanting to have things my own way-a failing to which I have certainly been prone. My personal interest in social conditions, I was told, was dictating the contents of the magazine and so standing in the way of the success it would enjoy if it were made more 'bright' and entertaining.

(15) Tom Hopkinson lost his job as editor of Picture Post after publishing a story on the treatment of political prisoners during the Korean War.

During their time in Korea Hardy and Cameron made three picture stories, the most dramatic of these being the record of General MacArthur's landing at Inchon, the port of Seoul. Seoul was not only the capital of Korea but the key centre of communications for the invading armies - North Koreans backed by Chinese - now operating far down to the south after driving the South Koreans and their allies into what Cameron called "the toehold enclave of Pusan". The Inchon landing effectively cut the legs from under the attackers, dramatically reversing the whole military situation. This was the second most powerful seaborne invasion ever launched - only that against Normandy five years earlier having been bigger - and our two men were the only British photo-journalists present.

The Inchon landing was not the only story our two men had sent back, and one of the others posed a problem. Text and photographs showed vividly how the South Koreans, with at least the connivance of their American allies, were treating their political prisoners, suspected opponents of the tyrant Synghman Rhee. Rhee himself would in due course be ditched as the insupportable head of an intolerable regime by the American protectors who had kept him in power for so long; but that was still ten years on into the future, and in the meantime Rhee and his henchmen were our gallant allies and the upholders of our Christian democratic way of life. By the 1980s we have all seen treatment of prisoners more openly murderous than that revealed in Hardy's pictures, and Cameron's accompanying article would today be accounted mild. But in the climate of that time, with British and Australian troops involved in the fighting, any criticism of South Koreans was certain to be regarded as criticism of 'our' side. Such criticism, moreover, being anti-Western, must inevitably be 'pro-Eastern', and hence - with only a small distortion of language - 'Communist propaganda', a crime of which I was already being accused by my employer.

(16) James Cameron, wrote about his experiences working with Bert Hardy as a war reporter in an article published in Picture Post: 1938-50 (1970)

I feel now that I must always have cut a rather futile figure as a war-correspondent, however often I was obliged to pose as one. For one thing I was almost continually afraid. Not particularly, I think, of getting killed, which seemed to be happening to most people, but of getting maimed and invalidated and left hanging around with legs or eyes and balls shot off; I never in the least fancied that. On the Korean assignment, as on many others, I was fortunately reinforced by my old mate and colleague Bert Hardy, and one of the good things about that was that Bert was no more of a John Wayne type than I. One of the daunting things in those days was to be attached to a cameraman with heroic instincts, who would follow the sound of the cannon as I follow the sound of the clinking glass, and who would shame one into dramatic gestures of great unwisdom.

Bert was, I am sure, as alarmed as I was, but there was one signal difference in our roles: he had to take the pictures, and it was long ago established that one way you cannot take pictures is lying face-down in a hole. I spent considerable periods of time doing that. Bert, on the other hand, was plying his trade upright in the open, cursing the military exigencies that had organized this invasion in the middle of the night. One of my enduring memories of that strange occasion is of Bert Hardy on the seawall of Blue Beach, blaspheming among the impossible din, and timing his exposures to the momentary flash of the rockets. That is the difference between the reporter's trade and the cameraman's. His art can never be emotion recalled in tranquillity. Ours can - or could be: the emotion is easy; the tranquillity more elusive.

(17) James Cameron, Picture Post (7th October, 1950)

They have been in jail now for indeterminate periods - long enough to have reduced their frames to skeletons, their sinews to string, their faces to a translucent terrible grey, their spirit to that of cringing dogs. They are roped and manacled. They are compelled to crouch in the classic Oriental attitude of submission in pools of garbage. They clamber, the lowest common denominator of personal degradation, into trucks with the numb air of men going to their death. Many of them are. The spectacle is utterly medieval. Among the crowds drifting indifferently around, a few bystanders take snapshots, grinning.

(18) The Times (25th October, 1950)

Mr Edward Hulton states with the deepest regret that, following a dispute about the handling of material about the Korean war, he has instructed Mr Tom Hopkinson to relinquish the position of editor of Picture Post. There is no personal hostility between Mr Hulton and Mr Hopkinson. Mr Ted Castle, associate editor of Picture Post and for six

years the assistant editor of the paper, is the new editor.

(19) Gerald Barry, letter to The Times (16th May 1957)

It is cowardly and defeatist to put the blame on competition from television; all commercial ventures have to stand up on their merits to competition with rival media. Picture Post has failed over these later years because it has been deprived of its initial sense of purpose, and in consequence has been forced to snatch at successive shifts and improvisations in

the attempt to hang on to a circulation failing for lack of resolute direction.

(20) James Cameron, Point of Departure (1967)

In fact Picture Post soon painlessly surrendered all the values (after Tom Hopkinson left) and purposes that had made it a journal of consideration, before the eyes ot its diminishing public it drifted into the market of arch cheesecake and commonplace decoration, and by and by it died, as by then it deserved to do.